Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Camila Xu and Version 1 by Senchang Hu.

Commonly recognized as an effective management technique, the use of incentives plays a vital role in the successful application of these approaches.

- inter-organizational incentive

- inter-organizational relationship

- multiple incentive

1. Introduction

Faced with the challenging and uncertain business climate, construction organizations are increasingly abandoning traditional paradigms of inter-organizational relationships to embrace cooperative business strategies and to collaborate more with other organizations, sometimes even with competitors. In other words, to foster superior project outcomes, organizations are increasingly transforming traditional adversarial relationships among project parties—caused by conflicts of goals and interests—into trust-based cooperative relationships. Industry leaders adopt a variety of approaches to achieve this, such as relational contracting, alliance building, partnering, and integrated project delivery (IPD) [1,2,3,4,5][1][2][3][4][5]. Commonly recognized as an effective management technique, the use of incentives plays a vital role in the successful application of these approaches [6,7][6][7].

Inadequate inter-organizational incentives can lead to a lack of motivation for participants to improve their performance. The existing literature on the use of incentives mainly focuses on addressing their significance [7,8,9,10][7][8][9][10] and explaining how they can be designed theoretically [11,12][11][12], lacking systematic research with empirical evidence from the perspective of the inter-organizational level.

2. Classification of Interorganizational Incentives

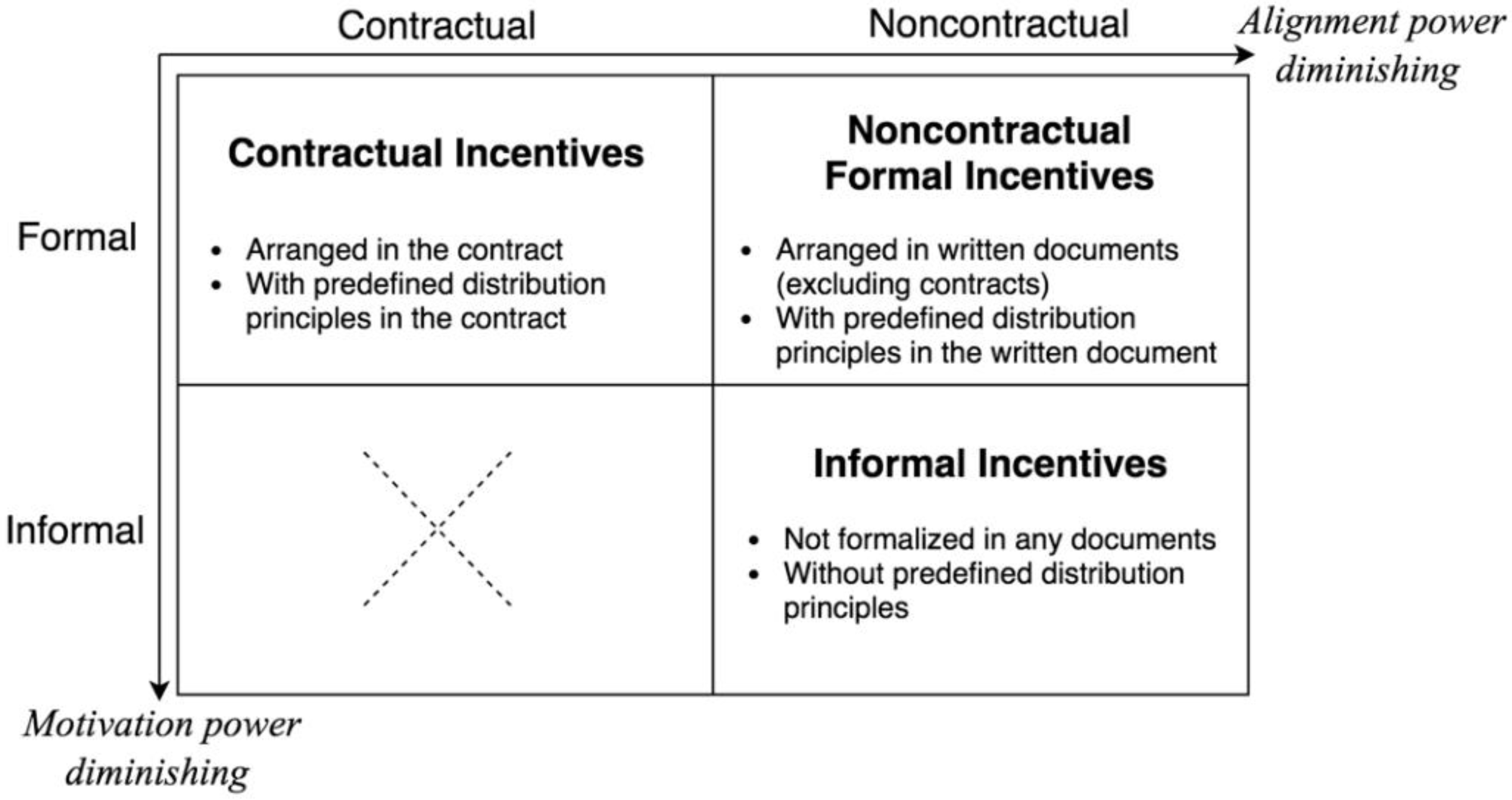

Incentives largely fall into two categories: intra-organizational incentives and inter-organizational incentives. Intra-organizational incentives have frequently been used to design compensation schedules as a way to improve productivity, generate higher job satisfaction, achieve optimal performance, and avoid project risks. Since employee and employer interests are not always aligned, various psychologists and economists have recommended intra-organizational incentives to motivate employees to work toward company goals [13,14,15,16][13][14][15][16]. The use of inter-organizational incentives is a managerial technique adopted by one organization to motivate another organization to achieve certain business goals. For example, some companies sign revenue-sharing contracts with their suppliers to improve the efficiency of their supply chains [17]. The revenue-sharing formula in such a contract is a kind of inter-organizational incentive. Interorganizational incentives differ from intra-organizational incentives in two contexts. First, organizations have more predictable rationality than individuals, which means that inter-organizational incentive design requires more rational and economic consideration [18,19][18][19]. In other words, while individuals have limited rationality and make decisions from complicated intrinsic motivations, commercial organizations typically follow the rational principle of maximizing their economic utility [20]. The economic utility in this context can refer either to short-term business profits or the long-term benefits of such intangible goods as reputation, social responsibility, and cooperative relationships [5]. Second, organizations have less control over the behavior of other organizations than they have over their own employees since their authority formally ends at the organizational boundary [20]. Such differences between inter-organizational and intra-organizational settings necessitate different incentive approaches and, thus, different application principles. Contractual incentives are provisions arranged explicitly in a contract [21], while non-contractual incentives are not mentioned in a contract. Formal incentives are distributed according to assessable performance against principles predefined in written documents [8]. On the one hand, if the written documents include a contract, such incentives are both formal and contractual. On the other hand, if incentive distribution principles are defined not in a contract but in other written documents (e.g., memos), such formal incentives are non-contractual. Lastly, informal incentives are neither predefined nor recorded in written documents. Thus, all informal incentives are essentially non-contractual. Figure 1 outlines this classification matrix, the cells of which are explained further below.

Figure 1.

Classification of inter-organizational incentives.

2.1. Contractual Incentives

Contractual incentives are the most extensively identified and commonly applied inter-organizational motivational tools and can be categorized across various dimensions [10]. For example, contractual incentives can be categorized according to the project performance parameters they address, e.g., cost, schedule, quality, safety, operation, and design optimization, either singly or in combination [8]. Contractual incentives can also be categorized as usual performance or superior performance according to whether the predefined performance measurement principles are business-as-usual or business-beyond-usual. Usual performance incentives are distributed if the mandatory minimum requirements specified in the contract are realized, while superior performance incentives are offered when exceptional performance—higher than the minimum requirement—is achieved [22,23][22][23].2.2. Non-Contractual Formal Incentives

If and when additional motivation is pursued after contract execution, non-contractual formal incentives can be applied. These incentives, while not set in a contract, are agreed upon by both business parties during the cooperation process and then formalized by written documents, e.g., statements or memoranda of understanding. Given the dynamic and uncertain business environment of the construction market, inter-organizational incentives are often deliberately arranged noncontractually to ensure a high degree of flexibility [24,25][24][25]. Non-contractual formal incentives are distributed in accordance with performance levels measured against principles predefined in formal, written documents [8]. For example, even with no contractually stipulated reward for top supplier performance, a client can follow company policy to offer a supplier additional bonuses for outperforming all other suppliers in the quarterly performance measurement. Non-contractual formal incentives have less legal force than contractual incentives and, thus, are less effective in terms of their power to align the client and the incentivized party (as represented on the x-axis in Figure 1).2.3. Informal Incentives

While not formalized in any documents, informal incentives can also be used to motivate an organization [26]. For example, a client can offer empowerment and commendations to project participants and verbally promise future business opportunities to suppliers. In some cases, the chance to participate in an iconic project itself can serve as an important informal incentive since working on such projects deepens the experience and bolsters reputations. Thus, simply by expanding the significance and platform of the project, a client can motivate other prospective project participants. Since informal incentives work as a kind of relational governance mechanism [27], they have more flexibility but less motivation power than formal incentives (as represented on the y-axis in Figure 1). In addition, because they are not memorialized in formal documents, most informal incentives are nonfinancial.3. Functions of Interorganizational Incentives

3.1. Benefit Sharing

The win–win philosophy underlying the use of inter-organizational incentives is evident in that any benefit gained from achieving incentive goals is shared among project participants [1,10][1][10]. Traditionally, because contracting approaches have focused on protecting clients against possible bad outcomes, they have generated detrimental adversarial relationships among contract parties [5,8,28][5][8][28]. However, alternative contracting approaches promote the use of incentives to reach project goals that, when met, generate benefits that clients are conditionally willing to share with the incentivized project parties [24]. Such benefit sharing indicates the client’s proactive inclination to cooperate with other project participants to generate superior outcomes; this proactive stance, in turn, evokes the intrinsic motivation of the participants to cooperate and perform positively. Benefit sharing also entails a pool of financial resources available to participants to offset any costs incurred for performance improvement [29,30][29][30]. This financial support enables them to make extra efforts required for improved performance. As a result, every project participant can benefit from achieving incentive goals. Through the interplay of these factors and the effects of the benefit sharing inherent to inter-organizational incentives, alternative contracting approaches can transform an adversarial business environment into a win–win culture of cooperative relationships.3.2. Goal Alignment

The goal alignment function of inter-organizational incentives entails the specification of client goals to the incentivized parties [8,10,31][8][10][31]. Although different project participants may share some common business goals, they usually have different priorities [5[5][8][10],8,10], which leads to misalignment. For example, a client typically pursues an optimal combination of cost, time, and quality performance, while a contractor organization may simply focus on maximizing its business profits [5,21][5][21]. By setting incentive goals in formal incentive schemes, the client organization conveys its specific project goals (e.g., superior quality or timely delivery) to other participants. In these formal specifications, the goals are linked to project performance measurement metrics and incentive payments [32,33][32][33]. Such incentive schemes reward the project participants financially [8,10,22,34][8][10][22][34] for achieving the client’s goals; conversely, these formal incentives may entail financial penalties if performance falls short of the incentive goals. As a consequence, the specification of incentive goals can reduce goal misalignment and establish mutual goals between the client and other project participants.References

- Bresnen, M.; Marshall, N. Motivation, Commitment and the Use of Incentives in Partnerships and Alliances. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2000, 18, 587–598.

- Lee, H.W.; Tommelein, I.D.; Ballard, G. Energy-Related Risk Management in Integrated Project Delivery. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2013, 139, A4013001.

- Lee, H.W.; Anderson, S.M.; Kim, Y.-W.; Ballard, G. Advancing Impact of Education, Training, and Professional Experience on Integrated Project Delivery. Pract. Period. Struct. Des. Constr. 2014, 19, 8–14.

- Rahman, M.M.; Kumaraswamy, M.M. Relational Contracting and Teambuilding: Assessing Potential Contractual and Noncontractual Incentives. J. Manag. Eng. 2008, 24, 48–63.

- Tang, W.; Duffield, C.F.; Young, D.M. Partnering Mechanism in Construction: An Empirical Study on the Chinese Construction Industry. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2006, 132, 217–229.

- Meng, X.; Gallagher, B. The Impact of Incentive Mechanisms on Project Performance. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2012, 30, 352–362.

- Suprapto, M.; Bakker, H.L.M.; Mooi, H.G.; Hertogh, M.J.C.M. How Do Contract Types and Incentives Matter to Project Performance? Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2016, 34, 1071–1087.

- Bower, D.; Ashby, G.; Gerald, K.; Smyk, W. Incentive Mechanisms for Project Success. J. Manag. Eng. 2002, 18, 37–43.

- Bubshait, A.A. Incentive/Disincentive Contracts and Its Effects on Industrial Projects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2003, 21, 63–70.

- Tang, W.; Qiang, M.; Duffield, C.F.; Young, D.M.; Lu, Y. Incentives in the Chinese Construction Industry. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2008, 134, 457–467.

- Choi, K.; Kwak, Y.H. Decision Support Model for Incentives/Disincentives Time–Cost Tradeoff. Autom. Constr. 2012, 21, 219–228.

- Shr, J.-F.; Chen, W.T. Setting Maximum Incentive for Incentive/Disincentive Contracts for Highway Projects. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2004, 130, 84–93.

- Kreps, D.M. Intrinsic Motivation and Extrinsic Incentives. Am. Econ. Rev. 1997, 87, 359–364.

- Prendergast, C. The Provision of Incentives in Firms. J. Econ. Lit. 1999, 37, 7–63.

- Rose, T.; Manley, K. Client Recommendations for Financial Incentives on Construction Projects. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2010, 17, 252–267.

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivations: Classic Definitions and New Directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2000, 25, 54–67.

- Narayanan, V.G.; Raman, A. Aligning Incentives in Supply Chains. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2004, 82, 94–102, 149.

- Smith, K.G.; Carroll, S.J.; Ashford, S.J. Intra- and Interorganizational Cooperation: Toward a Research Agenda. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 7–23.

- White, P.E. Intra- and Inter-Organizational Studies: Do They Require Separate Conceptualizations? Adm. Soc. 1974, 6, 107–152.

- Holmqvist, M. A Dynamic Model of Intra-and Interorganizational Learning. Organ. Stud. 2003, 24, 95–123.

- Stukhart, G. Contractual Incentives. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 1984, 110, 34–42.

- Blyth, A.H. Design of Incentive Contracts, Basic Principles. Aeronaut. J. 1969, 73, 119–124.

- Rose, T.; Manley, K. Motivation toward Financial Incentive Goals on Construction Projects. J. Bus. Res. 2011, 64, 765–773.

- Ling, F.Y.Y.; Rahman, M.M.; Ng, T.L. Incorporating Contractual Incentives to Facilitate Relational Contracting. J. Prof. Issues Eng. Educ. Pract. 2006, 132, 57–66.

- Woolthuis, R.K.; Hillebrand, B.; Nooteboom, B. Trust and Formal Control in Interorganizational Relations; Erasmus University Rotterdam: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2002; pp. 1–24.

- Schieffer, J.; Wu, S. Private Mechanisms, Informal Incentives, and Policy Intervention in Agricultural Contracts. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2006, 88, 1251–1257.

- Dekker, H.C. Control of Inter-Organizational Relationships: Evidence on Appropriation Concerns and Coordination Requirements. Account. Organ. Soc. 2004, 29, 27–49.

- Sakal, M.W. Project Alliancing: A Relational Contracting Mechanism for Dynamic Projects. Lean Constr. J. 2005, 2, 13.

- Daft, R.L.; Murphy, J.; Willmott, H. Organization Theory and Design; South-Western, Cengage Learning: Hampshire, UK, 2010; ISBN 978-1-84480-990-5.

- Tang, W.; Qiang, M.; Duffield, C.F.; Young, D.M.; Lu, Y. Enhancing Total Quality Management by Partnering in Construction. J. Prof. Issues Eng. Educ. Pract. 2009, 135, 129–141.

- Abu-Hijleh, S.F.; Ibbs, C.W. Schedule-Based Construction Incentives. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 1989, 115, 430–443.

- Ogwueleka, A.C.; Maritz, M.J. A Review of Incentive Issues in the South African Construction Industry: The Prospects and Challenges. In Proceedings of the ICCREM 2013, Karlsruhe, Germany, 7 October 2013; American Society of Civil Engineers: Reston, VA, USA; pp. 83–98.

- Richmond-Coggan, D. Construction Contract Incentive Schemes: Lessons from Experience; CIRIA: London, UK, 2001.

- Halman, J.; Braks, B. Project Alliancing in the Offshore Industry. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 1999, 17, 71–76.

More