Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Daniel Reyes-Haro and Version 2 by Rita Xu.

Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) is known as the main inhibitory transmitter in the central nervous system (CNS), where it hyperpolarizes mature neurons through activation of GABAA receptors, pentameric complexes assembled by combination of subunits (α1–6, β1–3, γ1–3, δ, ε, θ, π and ρ1–3). GABAA-ρ subunits were originally described in the retina where they generate non-desensitizing Cl- currents that are insensitive to bicuculline and baclofen. The GABAA-ρ receptors are proposed to be involved in extrasynaptic communication and dysfunction involves reduced expression in Huntington's disease (HD) and autism spectrum disorders (ASD).

- astroglia

- gamma-aminobutyric acid

- GABAAρ receptors

1. Introduction

Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) is a non-protein amino acid present in invertebrates and vertebrates, where is considered the main neural transmitter exerting inhibitory activity on neurons and their intricate networks [1][2][1,2]. However, this neurotransmitter depolarizes astrocytes and neural precursors through the activation of ionotropic GABAA receptors, pentameric proteins that are modulated by barbiturates and benzodiazepines [3][4][3,4]. Interneuron–astrocyte communication regulates excitatory/inhibitory (E/I) balance and gliotransmission is accepted to play an important role. Astroglia setting includes the expression of GABAA receptors to detect interneuron signaling and calcium transients derived from this communication promote the release of gliotransmitters like GABA, known as an important extrasynaptic source for tonic inhibition. In this scenario, the expression of GABAA-ρ subunits becomes relevant under physiological and pathological conditions. For example, during earlier postnatal neurodevelopment [5][6][7][8][9][10][5,6,7,8,9,10] and as a potential therapeutic target for post-stroke motor recovery [11].

2. Structural Properties, Characterization, and Functions of GABAA-ρ Receptors

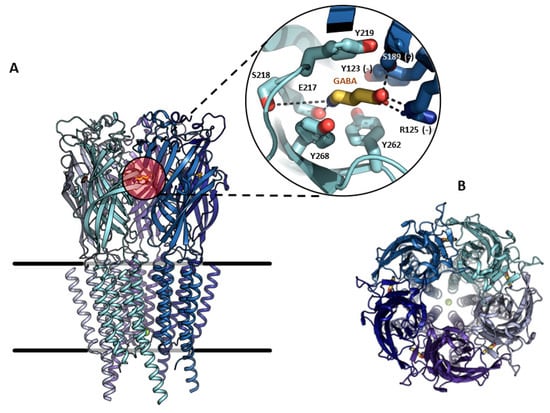

The GABAA receptor is an ion channel member of the ligand-gated ion channel (pLGIC) superfamily that opens transiently, inducing the inhibition of action potentials through an inward membrane chloride conductance [4][12][4,12]. It was identified through bicuculline sensitivity in autonomic brain terminals and in mammalian brain slices [13]. This receptor is widely distributed in the central nervous system (CNS) and combinations of nineteen subunits (α1–6, β1–3, γ1–3, δ, ε, θ, π and ρ1–3) occur to coordinate differential neural inhibitions, such as phasic or tonic receptors, depending on the stoichiometry of each channel [8][9][10][8,9,10]. In the adult brain, the most common arrangement is: α1 (2), β2/3 (1), and γ2 (2) [14][15][16][14,15,16]. Topologically, each subunit contains an amino-terminal domain, where the neurotransmitter recognition site is located, a short extracellular carboxy-terminal domain, two cytoplasmic loops, and four transmembrane regions (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Molecular structure and binding-site of the human GABAA-ρ1 receptor. (A). View of the pentameric receptor embedded in the plasma membrane, expanding in detail the orthosteric GABA binding site formed by the interface of two subunits in the amino-terminal extracellular domain. Residues interacting with GABA (yellow) from the main subunit (cyan), or complementary (–) subunit (deep blue), are indicated. (B). View of the pentamer from the outside of the membrane, showing the central ion-conducting pore. Structure representation was prepared using PyMOL v 2.5.2.

Each subunit is predicted to have a molecular weight between 48 and 64 kDa, based on the amino acid sequence, and form a central pore or ion channel. Pentameric complexes weigh approximately 275 kDa [4]. Classical GABAA receptors are known to desensitize upon continuous exposure to the ligand; however, GABAA-ρ subunits form functional homomeric receptors that do not desensitize [17][18]. GABAA-mediated signaling is a key element for the E/I balance of the brain and its dysfunction is linked to motor, cognitive, and psychiatric disorders [16]. GABAA-ρ was originally described as a retinal component. There are three genes of GABAA-ρ1-3 subunits; the first two were originally cloned from human retinal cDNA libraries [17][18][18,19], and the third from a rat retinal cDNA library [19][20]. The human GABAA-ρ1 subunit shows alternative spliced variants and two deletions of 51 and 450 nucleotides, respectively (GABAA-ρ1-51 and GABAA-ρ1-450), which brought speculations as to the regulation of the expression of full-length GABAA-ρ1 subunits, possibly co-assembling with some of the alternative spliced subunits and leading to variants with tissue-specific properties [20][21]. The first electrophysiological characterization was performed with the archetypical heterologous expression system for the study of ion channels, developed by Ricardo Miledi and collaborators, by injecting exogenous mRNA in Xenopus oocytes and using a two-electrode voltage clamp (TEVC) [21][22]. This pioneer group injected mRNA preparations from either the brain or retina in Xenopus oocytes and found different GABA responses, which were kinetically and pharmacologically different [4]. For example, a slight decay and the magnitude of the current remained almost at maximum as long as the agonist was present in the perfusion bath. On the other hand, GABA responses decayed quickly near the basal level [4]. The sensitivity to the agonist was also very different, as the retinal GABAA receptor presented an EC50 of 1.48 μM, in contrast to the brain cortex, (EC50 = 84.6 μM). The cloned cDNA coding for the GABAA-ρ1 subunit expressed in Xenopus oocytes displayed a GABA EC50 of 2 μM and was insensitive to bicuculline [4][17][4,18]; these results were like those obtained from oocytes injected with retinal mRNA. Several reports have shown heteromerization in different GABAA-ρ subunits [22][23][23,24], as well as in other GABAA subunits [8][24][25][26][8,25,26,27], or even in subunits belonging to different members of the pLGIC superfamily [27][28]. The homomeric GABAA-ρ1 subunit is insensitive to bicuculline and baclofen, commonly used to discriminate between heteromeric GABAA channels and metabotropic GABAB receptors, respectively [28][29][30][29,30,31]. The pharmacological distinctiveness that allowed the discriminating of GABAA-ρ subunits from different subunits of heteromeric GABAA receptors was the synthesis of conformationally restricted GABA analogues [31][32]. The cis-isomer, cis-4-amino-crotonic acid (CACA) and trans-4-amino-crotonic acid (TACA) are GABAA-ρ1 partial and potent agonists, respectively. Nonetheless, TACA is not selective and is also able to activate typical heteromeric GABAA receptors; this gives an advantage to using CACA to clearly identify GABAA-ρ subunits [32][33][33,34]. Homomeric GABAA-ρ1 receptors are insensitive to many of the heteromeric GABAA allosteric modulators, such as benzodiazepines and barbiturates. However, some drugs have powerful allosteric properties, like the anticonvulsant loreclezole [34][35] or drugs designed for specific purposes, such as (1,2,5,6-tetrahydropyridine-4-yl) methylphosphinic acid (TPMPA), -cis-/trans-3-aminocyclopentane) butylphosphinic acid ([±]-cis and [±]-trans-3-ACPBuPA, Piperidin-4-yl) methylphosphinic acid (P4MPA), Piperidin-4-yl seleninic acid (SEPI), and 3-(guanido)-1-oxo-1-hydroxy-phospholane (3-GOHP) [35][36]; all of them have been used as a source to investigate the involvement of GABAA-ρ receptors in sleep–waking behavior and antinociception in the peripheral nervous system or in learning, and also to investigate memory enhancers and other cognitive activities [35][36][36,37]. The importance of the GABAA-ρ receptor becomes increasingly clear through its wide expression in the CNS. Additionally, it is highly related to ammonia-induced apoptosis, retinitis pigmentosa, myopia, and may be important for some specific in vivo effects of ethanol and Huntington’s disease (HD) [16][37][16,38]. At the last stage of the preparation of this remanusearchcript the cryogenic electron microscopy structures of GABAA-ρ1 subunits was reported, in apo state as well as in the presence of TPMPA, picrotoxin (PTX), and GABA, generating different conformations [38][17]. This milestone is an exciting point in the state-of-the-art of the current research that will help reusearchers to understand the intricated mechanisms that pharmacologically and functionally define this family of proteins, as a natural step following the pioneering experimental achievements described here.

3. GABAA-ρ Receptors in Astroglia

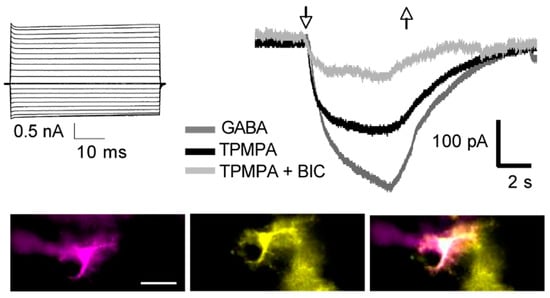

Neurons are considered the basic unit for information processing associated with perception and cognition. However, this neurocentric definition has been challenged because they only represent a fraction of the brain cells. Glial cells, on the other hand, are the dominant population and respond to neuronal activity through neurotransmitter receptor activation [39][90]. Although the precise decoding of neuron–glia communication in brain function is unknown, glial cells contribute to synapse formation, cell development, myelination, brain microcirculation, neuroprotection, and the modulation of neural activity [40][41][91,92]. In this context, the GABAA receptors mediating synaptic (phasic) or extrasynaptic (tonic) transmission are molecularly and functionally distinct for both neurons and glial cells [42][93]. Astroglial cells include astrocytes, ependymal cells, radial glia including Bergmann and Müller glia; all of them are identified by the expression of the cytoskeletal glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP). Astroglia express functional GABAA receptors, but their role in the CNS physiology is intriguing, since glial cells do not produce action potentials. Nevertheless, GABA depolarizes astrocytes through GABAA receptors but has unitary conductances and gating properties similar to those recorded in neurons [43][94]. Furthermore, specific differences in GABAA subunit expression were observed between primary cultures of rat cerebellar astrocytes and granular neurons [44][95]. Initial studies with RT-PCR reported that the total amount of GABAA receptor subunit mRNA in astrocytes was two orders of magnitude lower than in neuronal cells. Moreover, of all the GABAA subunits expressed by granular neurons, only α6 and γ2 subunits were not expressed by astrocytes. Another difference was that GABAA-α1, α3, and α5 subunits were abundantly expressed in granular neurons, while GABAA-α1 and α2 were predominant in cerebellar astrocytes. Likewise, GABAA-β1 and β3 were abundantly expressed in both cell types. Finally, GABAA-γ2 and GABAA-γ1 were prevalent in cerebellar granular neurons and astrocytes, respectively [44][95]. Studies in astrocytes isolated from the thalamus showed that all of them express functional GABAA receptors that responded to the selective agonist muscimol [45][96]. The same study showed a GABAA subunit expression profile through single cell RT-PCR studies. The prevalent subunits were GABAA-α2, GABAA-α5, GABAA-β1, and GABA A-γ1 [45][96]. Overall, these studies reported the heterogeneous expression of GABAA subunits associated with a brain region. Accordingly, astroglia showed differences in their responses to pharmacological modulators of GABAA receptors such as benzodiazepines and barbiturates [9][42][46][9,93,97]. For example, DMCM, an inverse benzodiazepine agonist that enhanced GABAA-mediated currents in astrocytes and inhibited them in neurons, suggests a different subunit composition [42][93]. Electrophysiological recordings on cerebellar astrocytes in situ showed a heterogeneous array of GABAA subunits because modulation by benzodiazepines was absent in Bergmann glia [46][97]. Moreover, modulation by barbiturates, such as pentobarbital, was present in Bergmann glia but absent in ependymal glial cells of the cerebellum [6][46][6,97]. These differences are related to a specific GABAA subunit array that includes GABAA-∆ or GABAA-ρ subunits in Bergmann glia and ependymal cells, respectively [6][46][6,97]. Additionally, the functional expression of GABAA receptors was reported in situ via in striatal astrocytes; pentobarbital modulation was absent and GABAA-ρ subunits were found in more than half of them [9] (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Functional expression of the GABAA-ρ subunit in astrocytes. Whole-cell patch-clamp recording of an astrocyte in a coronal slice of the dorsal striatum of a GFAP-EGFP mouse. A classic passive current profile obtained from a sulforhodamine B (magenta)-injected cell that was also GFAP-EGFP+ (yellow). The overlay of both signals confirms cell identity. Scale bar represents 20 μm. Membrane currents were evoked in 50 ms voltage steps ranging from −160 to +40 mV, from a holding potential of −70 mV. Astrocytes responded to GABA (10 μM) and the current was partially reduced by the selective GABAA-ρ antagonist TPMPA (100 μM); a further inhibition was observed when the selective GABA-A antagonist bicuculline (BIC, 100 μM) was added. The arrows indicate the start (up) and end (down) of the agonist/antagonist application.

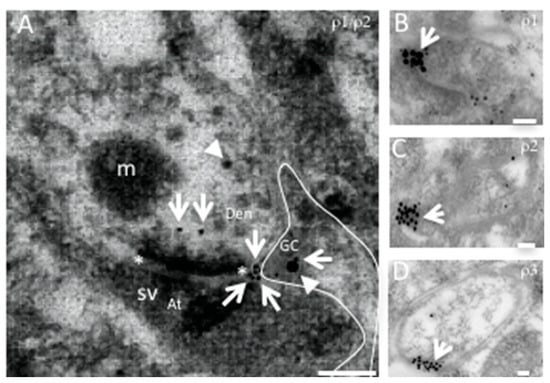

Figure 3. Representative electron micrographs of GABAA-ρ1-3 immunogold localization in mouse neostriatum. (A). Axon–dendrite synaptic connection co-expressing GABAA-ρ1 (arrow) and -ρ2, (arrowhead) and a positive glial cell process (GC) for both subunits (outlined). GABAA-ρ1 is located at peri- and extrasynaptic spaces. The synaptic active zone is marked with asterisks; presynaptic region is marked with (At: axon terminal), and postsynaptic with (Den: dendrite). GCs with perisynaptic processes showing GABAA-ρ1 (B), GABAA-ρ2 (C) and GABAA-ρ3 (D) immunogold localization. Scale bar 100 nm. (B–D). Expression of GABAA-ρ subunits in glial processes. Abbreviations: m: mitochondria, sv: synaptic vesicles. Scale bar 200 nm.