Legumes play a special role in this process, as they have unique characteristics with respect to storing protein and many other important components in their seeds that are useful for human and animal nutrition as well as industry and agriculture. A great advantage of legumes is the nitrogen fixation activity of their symbiotic nodule bacteria. This nitrogen self-sufficiency contributes directly to the challenging issue of feeding the world’s growing population. Molybdenum is one of the most sought-after nutrients because it provides optimal conditions for the maximum efficiency of the enzymes involved in nitrogen assimilation as well as other molybdenum-containing enzymes in the host plant and symbiotic nodule bacteria. Molybdenum supply improves seed quality and allows for the efficient use of the micronutrient by molybdenum-containing enzymes in the plant and subsequently the nodules at the initial stages of growth after germination. A sufficient supply of molybdenum avoids competition for this trace element between nitrogenase and nodule nitrate reductase, which enhances the supply of nitrogen to the plant

- molybdenum

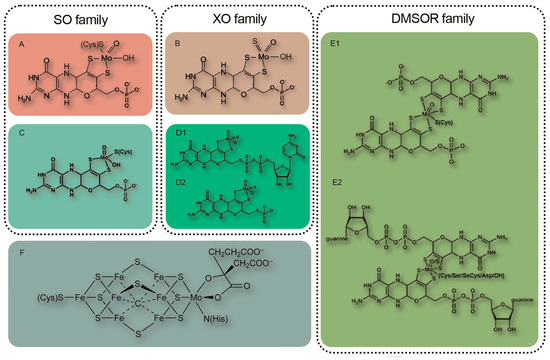

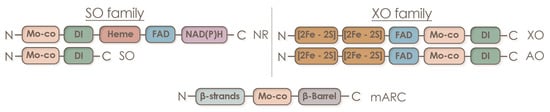

- molybdenum-containing enzymes

- nitrogenase

- nitrate reductase

- legumes

1. Introduction

2. Molybdenum Entry and Transport in Leguminous Plants

Molybdenum exists predominantly in its most oxidized form, the molybdate oxyanion (MoO42−), which is the major form predominant in soil solutions with pH levels above 4.2 [42][56] and can be absorbed by plant roots. In many soil types, a low bioavailability of trace elements predominates, leading to insufficient supply in leguminous plants. In response to Mo-limiting conditions, the endosymbiotic rhizobia in root nodule cortex cells reduce nitrogen fixation. Decreased molybdate bioavailability can occur in acidic soils (pH below 4.3) as a result of protonation to HMoO4− or MoO3 (H2O)3 [43][57] or strong absorption by iron oxyhydroxide, which is not bioavailable to plants [43][57]. In response to low molybdenum intake, plants have mechanisms that regulate molybdenum uptake, transport, and storage to adapt to Mo-deficient environments. Molybdenum homeostasis in plant cells is tightly controlled and likely plays a vital role in plant adaptation to the environment [21]. Thus, molybdenum is not only an essential element for plant growth and development but may also play an important role in the regulation of plant adaptation to adverse environmental conditions. Molybdenum is absorbed inside the cell in the form of molybdate. High-affinity transport systems are involved in this process [44][66]. Its further incorporation into the molybdenum cofactor precursor molybdopterin (MPT), a unique tricyclic pterin, does not require molybdate activation [45][46][67,68]; this process is described in detail in a review by Magalon and Mendel [47][69]. Thus, molybdenum is absorbed, transported, and most likely accumulated in the same molybdate form. In order for molybdate from the plant to reach the nodular bacterial cofactor of nitrogenase FeMoco, it must cross the cell plasma membranes and peribacteroidal membranes of the nodules as well as the outer and inner membranes of the bacteroid [48][70]. In addition to the nonspecific pathway of molybdenum uptake into plants, two families of molybdate-specific transporters, MOT1 and MOT2 [21][49][21,73], have been identified in eukaryotes that ensure molybdate enters the cell through the plasma membrane. The MOT1 transporter gene is found only in the genomes of algae, mosses, and higher plants. In contrast to the single copy of MOT1 found in the green alga C. reinhardtii [50][74], up to seven MOT1 copies are found in higher plants. Two copies of MOT1 are present in Arabidopsis [51][52][75,76], rice, and maize, and more than four copies are found in plants of the legume family, including Lotus japonicas, Medicago truncatula, and soybean (Glycine max) [21]. A comparison of MOT1 homology in legume plants showed a high similarity between legume MOT1 and other MOT1 proteins from different organisms [53][77]. The increase in MOT1 copy number encoded by legume genomes is likely related to the need to bind more molybdenum, which is required for FeMoco nitrogenase biosynthesis to enable symbiotic nitrogen fixation. Molybdenum has been shown to be transported by two of the five MtMOT1;2 and MtMOT1;3 transporters in M. truncatula [54][55][78,79]. Although MOT1 plays a critical role in molybdenum uptake and transport depending on the level of molybdenum added [51][52][56][75,76,81], the precise determination of its function has been difficult [53][77]. The determination of its precise subcellular localization also interferes with this. MOT2 superfamily proteins are different from MOT1 proteins and have been found in plants and animals. It should be noted that the MOT2 family of transporters was first identified molecularly in Chlamydomonas [57][82]. MOT2 shows a lower affinity for molybdate transport (Km 550 nM) than MOT1 and is blocked by tungsten. Of particular interest is that the expression of the MOT2 gene is activated by molybdate deficiency and is unresponsive to nitrate availability. The latter represents an opposite regulation to that of MOT1 [58][83]. It is also important to note the important cellular proteins that are involved in the transport, distribution, and incorporation of the pterin cofactor into molybdenum enzymes which lack Moco-dependent enzymatic activity, e.g., the homotetrameric Moco transfer protein (MCP1) found in the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii [14]. This protein has a high Moco binding affinity and plays a key role in maintaining and storing the cofactor in its active form under aerobic conditions [59][85]. MCP and other similar proteins have been described in various plant species [14].3. Molybdenum Distribution and Recycling in Ontogenesis and Accumulation in Seeds

During the course of ontogenesis, molybdenum requirements and its accumulation in different plant organs vary significantly. This is due to changes in the intensity and localization of processes involving this trace element. Molybdenum is rapidly assimilated and transported through the plant as molybdate [60][61][51,87]. During the growing season, molybdenum is unevenly distributed in the plant and rapidly moves from one organ to another. In yellow lupine, the plant begins to absorb molybdenum from the soil in the seedling phase, a process that gradually intensifies until the phase of fruit formation. Molybdenum uptake in soybean, in contrast to lupine, starts only 25–30 days after sowing [62][55]. From the beginning of the grain formation phase, the uptake of molybdenum from the soil by lupine stops, and it is redistributed among the organs of the plant. At this point, the outflow of molybdenum from stems, nodules, and—to a lesser extent—leaves to the forming beans begins. In contrast to lupine, the outflow of molybdenum from stems and nodules in soybeans to seeds during this growth phase is insignificant [62][55]. Molybdenum gradually moves through the plant during ontogenesis, accumulating in stems, nodules, and finally reproductive organs and seeds. The accumulation of mineral nutrients in seeds is determined by a series of complex processes that begin with uptake from the rhizosphere, membrane transport in roots, translocation and redistribution within plants through xylem and phloem systems, and import and deposition in seeds [63][88]. During the development of legume seeds, various nutrients, including mineral compounds, are stored there. Mineral accumulation in seeds depends on the continuous absorption, movement, and recycling of mineral nutrients from vegetative organs and tissues, as well as senescent nodules, to their storage sites, the reproductive organ pods, and seeds. Most of these minerals eventually enter the seeds through the phloem pathway [64][89].4. Forms of Molybdenum in Legume Seeds

Legumes are known for their ability to concentrate molybdenum in significant quantities without causing a negative effect on themselves [65][66][100,101]. When molybdenum fertilizers are applied, legumes can concentrate the element almost in proportion to the doses applied [65][100]. Many representatives of the family Leguminosae accumulate significant amounts of this trace element in their seeds. When lupine is fertilized with molybdenum, the content of trace element in the seeds increases by 7–20 times when compared with controls [67][102]. The form in which molybdenum is contained in the seeds of leguminous plants has not yet been fully clarified. In plants, molybdenum is found in a mobile, easily extractable state, and only a small part is bound to proteins [68][69][52,97]. The distribution of molybdenum in the morphological parts of lupine seeds (germ axils, cotyledon, and seed coat) remains relatively constant and depends little on the availability of the micronutrient. The highest specific content of molybdenum is found in germ axils and its main stock, reaching 90% in cotyledons. Consequently, the molybdenum enrichment of seeds occurs mainly at the expense of seedpods. Some researchers have observed a large variety of compounds of pterin nature in the seedpods and roots of germinating soybean seeds [70][103], which could indicate the presence of molybdenum-containing enzymes with Moco [18]. It has proven challenging to determine the enzymatic activity of molybdenum-containing plant proteins in dry lupin seeds. In one study, the presence of Moco was determined using the standard method involving a complementation reaction with the nit-1 mutant of Neuspora crassa [71][107], which allows for the detection of any type of Moco (free and bound) that can be incorporated into the mutant apoprotein. However, in other studies, the confirmation of the presence of two molybdenum-containing proteins in dried yellow lupin seeds was obtained using a highly sensitive method involving the radioactive isotope tungsten as an analog of molybdate [72][73][108,109]. By using radioactive tungsten labeling “in vitro” on a radioautograph gel after the electrophoresis of lupine seed extract, it was possible to detect two intense radioactive bands corresponding to proteins that were bound in significantly higher amounts than other proteins in the extract. The results of a size exclusion chromatography study of pea and lentil seed extracts where molybdenum species were quantified via SEC-ICP-MS showed that the elution profiles of molybdenum were quite different between the two extracts [74][49]. In the lentil extract, the main peak of molybdenum appeared in the high molecular weight region (about 200,000 w/w) accompanied by another in the low-molecular-weight region (<2000 w/w), whereas in pea extract (similar to white beans and soybean meal [75][50]) almost all molybdenum was eluted from the column as one peak in the low molecular weight region. Additional similar experiments were also carried out [76][110].5. Competition for Molybdenum and the After-Effects of Its Accumulation in Seeds

In the initial growth period, as noted for soybean and lupine [69][77][97,111], molybdenum gradually moves from the cotyledons to become localized in young shoots. During the germination phase, the trace element is intensively accumulated in stems. This organ retains its leading position in molybdenum accumulation in plants up until the nodulation stage. Most of the initial stock of molybdenum in the seeds is transferred to the plant before the flowering stage. The delivery of metals to seeds and young leaves appears to occur through the phloem [78][112]. In stem nodes and minor veins, the metal is most likely transferred from the xylem to the phloem [79][113]. This initial molybdenum storage in the seeds is important for the initial growth phases of lupine, determining the intensity of nitrate assimilation. The initial stock of molybdenum in the seeds also has a significant influence on the later phases of growth. After nodulation (the four-leaf phase), significant amounts of molybdenum (30–35% of the total molybdenum in the plant) are present, transported mainly from the lupine seed cotyledons [68][69][80][52,97,114]. The molybdenum reserve in seeds provides enough for the initial requirements of the emerging plant in the early stages of growth and is therefore crucial for nitrogen nutrition in legumes. The mechanism underlying molybdenum accumulation in plants is not yet well understood. However, it is of considerable interest, especially in the case of symbiotic systems, where the functioning of the enzymatic systems in the host plant and the symbiont bacteria depends on the amount of molybdenum accumulated in the seeds. Plants grown from molybdenum-enriched seeds have increased nitrate reductase and nitrogenase activity, which ultimately leads to additional yields. Thus, molybdenum accumulation in the first year can have a positive effect on two generations of plants [60][51]. The effects of applying molybdenum to legumes are beneficial in terms of improving the functionality and efficiency of the rhizobial complex to provide nitrogen to the plant, increasing yields, and accumulating trace elements in the seeds. Biological nitrogen fixation is stimulated when molybdenum is applied to legumes, particularly soybeans [81][43]. Grain legumes show the highest need for molybdenum during budding and early flowering, a lack of which inhibits the formation of a symbiotic nitrogen fixation system and the simultaneous use of two sources of nitrogen by the plant: molecular nitrogen during nitrogen fixation and nitrate nitrogen during nitrate reduction [68][80][52,114]. When a molybdenum deficiency occurs, all trace elements available in the nodules and coming from the soil are incorporated into nitrogenase, and the plant is deprived of the opportunity to use nitrate and molecular nitrogen simultaneously for nutrition. A determination of nitrate reductase activity in the different organs of lupine showed that this activity was significantly stimulated by molybdenum supplementation in the leaves and nodules, while in the roots, where nitrate reductase activity is rather low, the stimulation was weaker. Nitrogen and molybdenum feeding showed no advantage over molybdenum feeding alone. Furthermore, an especially strong stimulation of nitrate reductase activity (3.5 times) was observed in a variant where seeds from the previous year enriched with molybdenum due to the foliar feeding of lupine with molybdenum were used (22.2 mg/g; the control had 10.4 mkg/g). In these studies, the application of molybdenum at the budding/early flowering phase as well as the after-effect of molybdenum accumulation in the seeds caused by the foliar feeding of lupine with molybdenum in the previous year, resulted in the stimulation of nitrogen fixation activity in the nodules. Hamaguchi also indicated that the enrichment of the seeds with molybdenum eventually increased the biological nitrogen fixation, growth, and yield of the crop [82][117]. Molybdenum fertilization increases the protein content [83][118] of legume seeds and leads to a significant accumulation of molybdenum within them. In one study, a foliar application was found to be more efficient in producing enriched molybdenum seeds [81][43] than seed treatment with microelements. Similar findings were obtained in yellow lupine, where pre-sowing treatment was effective only in three out of four years [68][69][52,97]. Plants grown from molybdenum-enriched seeds have significantly higher nitrate reductase activity than control plants or plants that receive molybdenum from seed treatments before sowing [68][52]. Thus, the molybdenum contained in seeds has a significant impact on the growth of plants and most effectively supplies their needs for this micronutrient. A direct correlation between molybdenum content in seeds and yield has also been shown for soybeans [77][84][85][86][111,119,120,121]. Sowing seeds with a high molybdenum content has also been shown to improve the growth and nodulation of Phaseolus vulgaris plants. Furthermore, research also shows the benefits of seeds with high concentrations of molybdenum for improved bean yields [87][88][122,123]. On the contrary, low molybdenum in seeds sharply hinders nitrogen fixation and nitrate assimilation before the phase of budding, causing delayed plant growth and simultaneously reducing the absorption of molybdenum from the soil during the time where demand for this trace element in soybean is at a maximum [62][89][55,126]. Molybdenum content in seeds is the most informative indicator of the degree of plant provision of this trace element [90][127]. During the pre-sowing treatment of soybean seeds with molybdenum salts, only a small proportion of the trace element passes from the initial seeds to the seeds of the future crop [77][84][111,119]. The substantial accumulation of molybdenum in seeds, required to cause its after-effect, occurs only with the foliar feeding of lupine in the phase of its maximum demand for this trace element. This ensures the effect of molybdenum by enhancing the mechanisms of nitrogen assimilation, which ultimately increases the seed yield.6. Benefits of Sufficient Molybdenum Intake in Legumes

Since molybdenum is a component of numerous molybdenum-containing enzymes found in the symbiotic system of leguminous plants, its influence is far from being limited to participation only in nitrogen assimilation (Table 1).

| Enzyme | Function |

|---|---|

| nitrate reductase (NR) | NR catalyzes two-electron reduction of nitrate to nitrite as a key step of the inorganic nitrogen assimilation pathway [7]. NR may play a role in NO homeostasis by supplying electrons from NAD(P)H through its diaphorase/dehydrogenase domain [91][136]. NO3− + NAD(P)H + H+ = NO2− + NAD(P)+ + H2O |

| sulfite oxidase (SO) | SO catalyzes the two-electron oxidation of sulfite to sulfate, the final step in the degradation of sulfur-containing amino acids in sulfur catabolism [7]. In plants, SO is involved in plant protection from sulfite toxicity under a SO2-rich atmosphere [92][137]. SO32− + H2O + O2 → SO42− + H2O2 |

| mitochondrial amidoxime reducing component (mARC); NO forming nitrite reductase (NOFNiR) |

mARC catalyzes the reduction of hydroxylated compounds, mostly N-hydroxylated nucleobases and nucleosides: N-hydroxycytosine (NHC), the base analogue of 6-hydroxylaminopurine (HAP; in plants [93][138]), N-hydroxycytidine, and N-hydroxyadenosine [58][94][83,139]. NOFNiR activity can catalyze nitric oxide (NO) formation from nitrite and is strictly dependent on NR diaphorase activity but is independent of the NR Moco domain [95][96][97][140,141,142]. Plant NRmARC complex is an efficient mechanism for NO synthesis under physiological conditions, aerobiosis, and in the presence of both nitrate and nitrite. oxime + NADH = imine + NAD+ or amine − N-oxide + NADH = amine + NAD+ |

| xanthine oxidoreductase (XOR) | XOR performs the last two steps of purine catabolism by mediating the oxidation of hypoxanthine to xanthine and xanthine to uric acid [7] (xanthine dehydrogenase (XDH) activity); participates in purine catabolism that produces reactive oxygen species (ROS) [98][143] (xanthine oxidase (XO) activity); generates nitric oxide (nitrite reductase activity); and shows NADH oxidase activity yielding NAD+ and superoxide [99][144] (NADH oxidase activity) [100][145]. Plant XOR can participate in reactive oxygen species metabolism, contributing to pathogen resistance by generating H2O2, and it can also produce uric acid and remove H2O2 from chloroplasts under conditions of oxidative stress [101][146]. |

| aldehyde oxidase (AO) | AO oxidizes a variety of aldehydes, purines, pteridines, and heterocycles with O2 as the terminal electron acceptor generating H2O2 [102][147]. AO is essential for the biosynthesis of the stress hormone abscisic acid and indole-3-acetic acid in plants [7]. aldehyde + H2O + O2 = carboxylate + H2O2 |