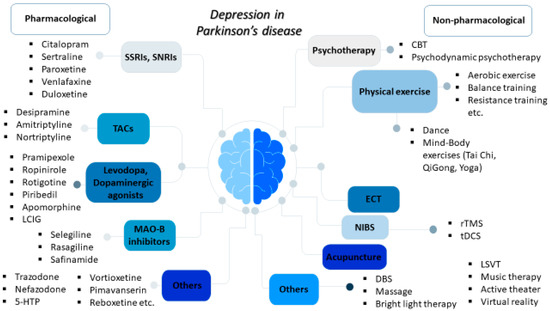

Depression represents one of the most common non-motor disorders in Parkinson’s disease (PD) and it has been related to worse life quality, higher levels of disability, and cognitive impairment, thereby majorly affecting not only the patients but also their caregivers. Available pharmacological therapeutic options for depression in PD mainly include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, and tricyclic antidepressants; meanwhile, agents acting on dopaminergic pathways used for motor symptoms, such as levodopa, dopaminergic agonists, and monoamine oxidase B (MAO-B) inhibitors, may also provide beneficial antidepressant effects. There is a growing interest in non-pharmacological interventions, including cognitive behavioral therapy; physical exercise, including dance and mind–body exercises, such as yoga, tai chi, and qigong; acupuncture; therapeutic massage; music therapy; active therapy; repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS); and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) for refractory cases.

1. Introduction

Neurodegenerative diseases cause a substantial health burden worldwide and their prevalence is on the rise. After Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the second most frequent neurodegenerative disorder, affecting more than 1% of the elderly population

[1]. The exact pathogenesis of PD remains obscure; although, several genetic factors and environmental exposures, as well as a complex interaction between them, contribute to its development

[2][3][2,3]. Concerning the underlying mechanisms, mitochondrial dysfunction, autophagy dysregulation, neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, and proteasome impairment have been shown to play a pivotal role

[2][4][2,4]. The neuropathological hallmarks of PD are the progressive loss of dopaminergic neuronal cells in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc) in the midbrain and the accumulation of Lewy bodies and Lewy neurites, which primarily consist of alpha-synuclein protein aggregates

[2]. The cardinal motor features of PD include resting tremors, rigidity, bradykinesia, and postural instability while most PD patients also experience non-motor symptoms, such as sleep disorders, autonomic dysfunction, cognitive decline, psychotic manifestations, anxiety, and depression

[5]. Non-motor symptoms may actually be more burdensome compared to motor ones and, although levodopa still represents “the gold standard” approach for the symptomatic treatment of PD motor symptoms, the management of non-motor manifestations is especially challenging

[6].

Depression represents one of the most common non-motor disorders in PD, affecting approximately 30–40% of PD patients; although, epidemiological evidence across different studies varies widely

[7]. In PD, depression has been associated with reduced quality of life, worse levels of disability, cognitive impairment, and increased mortality and morbidity, thereby majorly affecting both patients and their caregivers

[6]. Depression appears in all PD stages and it may precede the onset of motor impairment during the prodromal stages of the disease

[6]. Risk factors for depression in PD include female sex, increased physical dependence, higher levodopa dose, more severe motor impairment, pain, and daytime sleepiness

[8]. Clinically, PD patients with depression display less prominent guilt and self-hate compared to depressed non-PD individuals; meanwhile, the core symptoms of loss of satisfaction, enjoyment/pleasure, and appetite commonly occur

[6]. The underlying pathophysiological mechanisms of PD depression are complex, involving impaired cortico-striatal and limbic brain circuits, an imbalance between neurotransmitter systems (mainly serotoninergic, dopaminergic, and noradrenergic), neuroinflammation, and the dysregulation of neurotrophic factors

[8].

Depression in PD might go unrecognized since some symptoms, including weight loss, sleep disturbances, psychomotor slowing, and fatigue, can be attributed to the disease itself, regardless of the co-occurrence of depression

[9][10][9,10]. The early diagnosis and effective treatment of PD depression are of paramount importance and involve both pharmacological and non-pharmacological therapeutic interventions. However, evidence of the effectiveness and safety of antidepressant medications used against depression in PD is inconsistent, the optimal treatment approach is uncertain, and its management may be challenging

[11]. Definite guidelines for PD depression are also lacking

[12]. Furthermore, although several non-pharmacological interventions have shown promising potential in the management of PD depressive symptoms, it is still unclear which of these interventions are the most appropriate and for which PD stage under which circumstances. Currently, dual serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), such as nortriptyline and venlafaxine, and selective serotonin and reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), such as fluoxetine and citalopram, are generally firstly recommended, followed by tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs)

[12]. In addition, physical exercise; psychotherapy mainly in the form of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT); and repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) can also be considered, despite the inadequately robust evidence

[6][11][13][6,11,13].

2. Pharmacological Treatment Approaches for Depression in PD

The use of antidepressant medications, including SSRIs, SNRIs, and TCAs, is the most common treatment strategy for PD depression

[14]. It is estimated that up to 25% of PD patients may be on antidepressants at anytime during the course of the disease

[15] and SSRIs are more frequently prescribed compared to TCAs

[16]. Agents acting on dopaminergic pathways, such as levodopa, dopaminergic agonists, and monoamine oxidase B (MAO-B) inhibitors, may also display antidepressant effects. The following subsections will discuss recent evidence of the role of pharmacological interventions currently used in PD depression, as well as the potential effects of other drugs that are currently under clinical investigation (

Figure 1 and

Table 1).

Figure 1.

Overview of the pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments for depression in Parkinson’s disease.

Table 1.

Main types and examples of pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments for depression in Parkinson’s disease.