Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Fanny Huang and Version 1 by Cesar A. Moran.

Primary carcinomas of the lung are vastly represented by the conventional types of adenocarcinomas or squamous cell carcinomas. Spindle cell and/or giant cell carcinomas, although uncommon represent an important group of primary lung carcinomas.

- primary pulmonary carcinomas

- carcinoma

- giant cells

- spindle cells

1. Introduction

Primary carcinomas of the lung are dominated by the conventional types, namely adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. In the current practice, with the use of immunohistochemical analysis using markers to either document pneumocytic or squamous differentiation, namely, the use of p40, keratin 5/6, p63, TTF-1, Napsin A, the vast majority of non-small cell carcinoma can be specifically categorized. The percentage of non-small cell carcinoma that do not show specific lineage for either pneumocytic or squamous differentiation is rather limited to no more than 2–3%. However, there is a small percentage of primary malignant neoplasms of the lung that show morphological features that depart from the conventional histologies and that may be composed of spindle cells and/or giant cells. This group of tumors, although well-recognized in the literature, for the most part, it has been coded under different designations in the past [1,2,3,4,5][1][2][3][4][5]. Even though some tumors may show an additional component of the conventional non-small cell carcinoma, there are some other tumors that may be exclusively composed of either spindle or giant cells.

2. Clinical Features

In the largest series of these tumors, there does not appear to be a predominant gender although men appear to be slightly more affected than women. The average age for the appearance of this tumor is about 63 years. The symptomatology of these patients will vary depending on the location and the size of the tumor. Patients with tumors in a central location will show symptoms of obstruction such as dyspnea, cough, and shortness of breath, while patients with peripheral tumors are likely to present with chest pain and shortness of breath.3. Pathological Features

3.1. Biopsy Interpretation

One important shortcoming in the interpretation of spindle and/or giant cell carcinomas is when the only tissue available for interpretation is a small biopsy specimen. Often pathologists are faced with the interpretation of small fragments of tissue from patients with a large pulmonary mass but in which the patient may be in the advanced stages of the disease requiring medical intervention rather than surgical resection. These cases pose a significant problem not in the interpretation of malignancy but rather in the interpretation of the specific subtype of carcinoma that could be further analyzed by advanced methods such as molecular techniques. Classifying these tumors as “Sarcomatoid” may be to some extent misleading as one is evaluating only a minor percentage of the tumor, even though that fragment of tissue may sow the morphological features of a spindle cell neoplasm. In such cases, two additional paths of care should be followed: (1) the use of more current immunohistochemical methods to properly determine whether the tumor has squamous or pneumocytic differentiation. Having the benefit of more specific immunohistochemical stains (pneumocytic and squamous markers), the tumor may be assigned to a specific category stating that the tumor has a spindle or giant cell morphology; (2) in cases in which the pneumocytic and squamous markers are negative and only keratin is positive, the appropriate interpretation in a small fragment of tissue would be that of non-small cell carcinoma with spindle and/or giant cell features that may represent pleomorphic carcinoma. Nevertheless, the definitive classification of such tumors should be performed only after a surgical resection takes place so that more sampling is available for interpretation and proper immunohistochemical stains are performed.

In terms of molecular profiling, if the material available for such analysis is the small biopsy, it should be carefully stated that even though the morphology is that of a “sarcomatoid” carcinoma, more definitive classification should not be based on this small fragment of tissue but after a surgical resection becomes available. If the results of the molecular profiling results are those that may be seen in adenocarcinomas or squamous cell carcinoma, then such tumor should be allocated in that subclassification.

3.2. Macroscopic Features

Tumors that histologically show spindle and/or giant cells cannot be separated on macroscopic grounds from other types of non-small cell lung carcinomas. The tumors can be centrally or peripherally located. The tumor size has been described as ranging from 2 to more than 10 cm in greatest diameter, with or without areas of necrosis or hemorrhage. When the tumors are not necrotic, the color can vary from white to gray and may have soft or mucoid consistency [10,13,33][6][7][8]. The only tumor that appears to show a different color is the one that is rich in osteoclast giant cells, which shows a reddish color [34][9].

3.3. Microscopic Features

The different histopathological features and the respective immunohistochemical analysis is presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Combination of morphological features, immunohistochemical features with suggested interpretion.

| Tumor Characteristics | Immunohistochemistry | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Pure Spindle cell morphology | Keratin positive spindle cells | |

| Negative TTF-1 and Napsin | ||

| Negative p40/p63/keratin 5/6 | Sarcomatoid carcinoma | |

| Pure spindle cell morphology | Positive TTF-1/Napsin | Sarcomatoid Adenocarcinoma |

| Pure spindle cell morphology | positive p40/p63/keratin 5/6 | Sarcomatoid squamous cell carcinoma |

| Mixed Spindle and giant cells | keratin positive spindle cells | Pleomorphic carcinoma |

| Mixed spindle with areas of adenocarcinoma | TTF-1/Napsin positive spindle cells | Sarcomatoid Adenocarcinoma |

| Mixed spindle cells with areas of adenocarcinoma | TTF-1/Napsin negative in spindle cells | Dedifferentiated Adenocarcinoma |

| Mixed spindle cell with areas of squamous carcinoma | p40/p63/keratin 5/6 positive spindle cells | Sarcomatoid squamous cell carcinoma |

| Mixed spindle cells with areas of squamous carcinoma | Negative p40/p63/keratin 5/6 in spindle cells | Dedifferentiated Squamous cell carcinoma |

| Pure Giant cell morphology | giant cells positive for keratin only | Giant cell carcinoma, Null cell type |

| Pure Giant cell morphology | giant cells positive for HCG | Giant cell carcinoma with syncytiotrophoblast-like |

| Cells | ||

| Pure giant cells with areas of adenocarcinoma | giant cells positive for keratin and TTF-1/Napsin | Giant cell adenocarcinoma |

| Pure giant cell with areas of adenocarcinoma | ||

| Or squamous carcinoma | giant cells positive for CD68/cathepsin/histone H3 | Adenocarcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma with |

| Osteoclast giant cell component. |

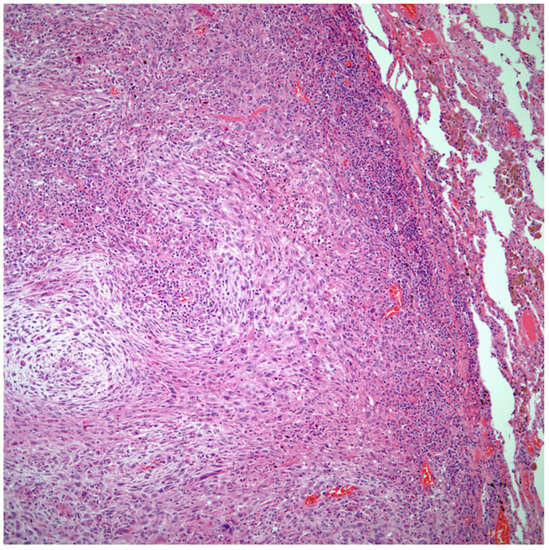

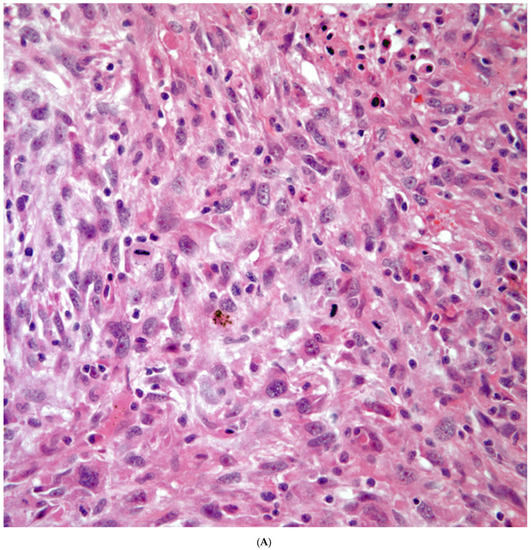

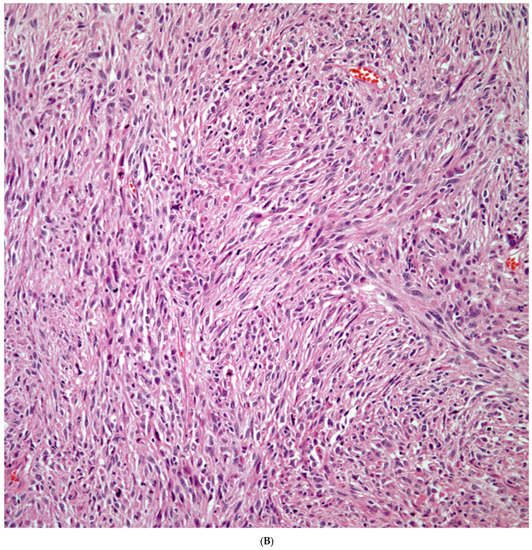

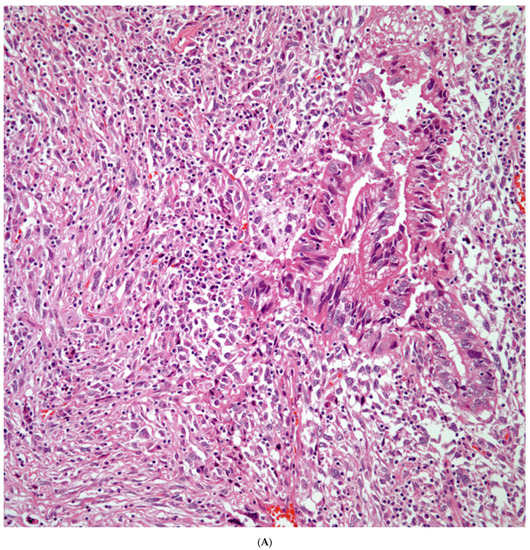

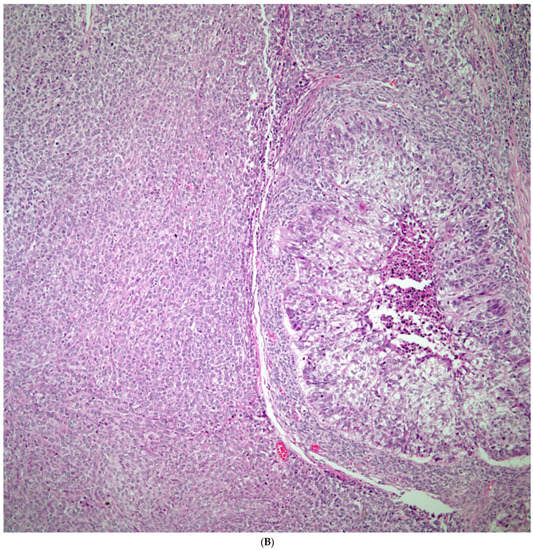

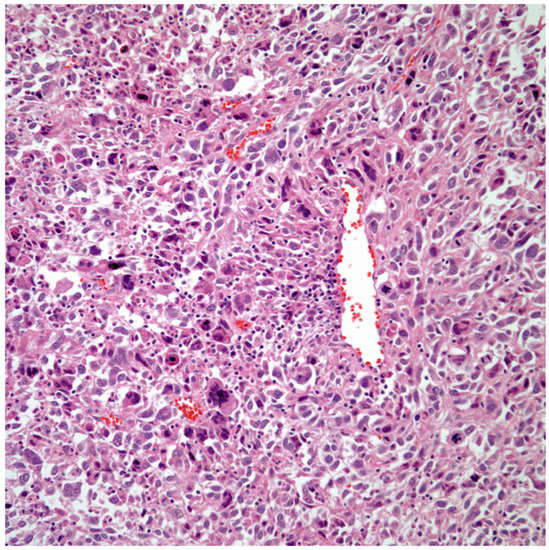

Sarcomatoid carcinomas: These tumors show a tightly packed spindle cell proliferation composed of slender cells with fusiform nuclei and inconspicuous nucleoli, replacing normal lung parenchyma. The tumors are well delimited but not encapsulated (Figure 1). Cellular atypia is variable and may show areas of mild to moderate to marked atypia. Mitotic figures also vary and may be inconspicuous or may be evident with the presence of atypical mitotic figures (Figure 2A,B). In high-grade tumors, the presence of necrosis and hemorrhage is prominent and is mixed with the neoplastic component. Important to recognize is that sarcomatoid carcinomas may be associated with areas of otherwise conventional non-small cell carcinoma such as adenocarcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma (Figure 3A,B). In addition, sarcomatoid carcinoma may also show the presence of bizarre giant cells admixed with the spindle cell component (pleomorphic carcinoma) (Figure 4).

Figure 1. Sarcomatoid carcinoma of the lung showing a well circumscribed tumor replacing lung parenchyma.

Figure 2. (A) Atypia and mitotic activity. (B) Neoplastic spindle cell proliferation.

Figure 3. (A) Sarcomatoid carcinoma associated with areas of conventional adenocarcinoma; (B) Sarcomatoid carcinoma associated with areas of squamous carcinoma.

Figure 4. Sarcomatoid carcinoma with giant cell component (pleomorphic carcinoma).

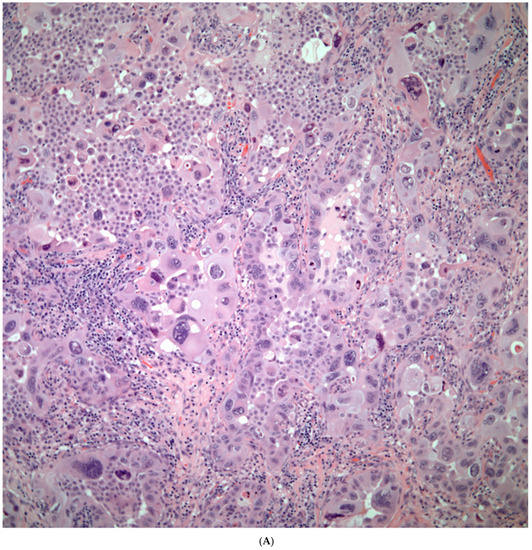

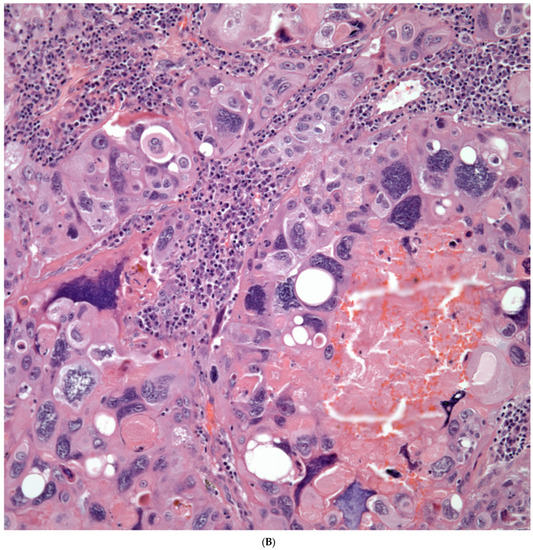

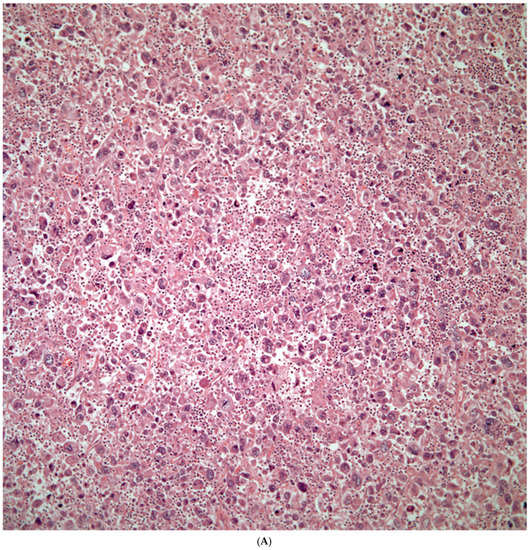

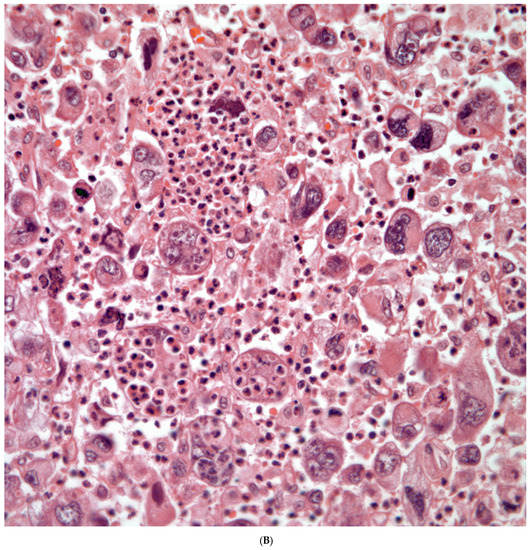

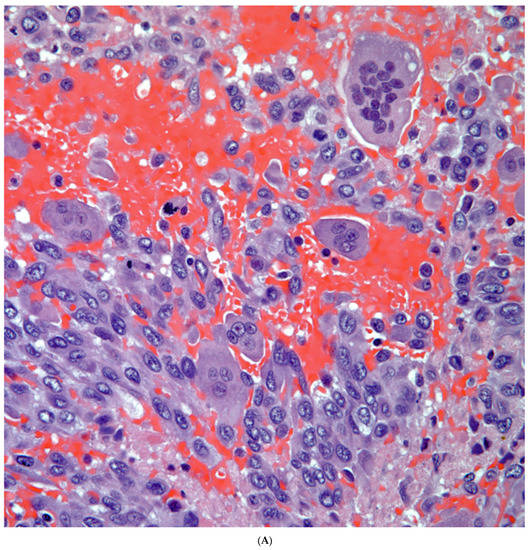

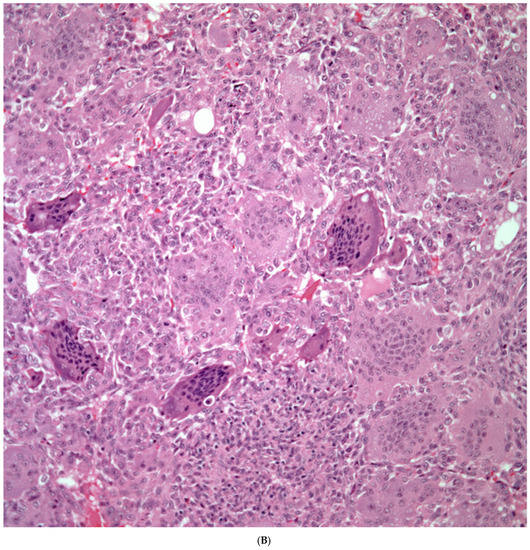

Giant Cell Carcinomas: These tumors may show predominantly a neoplastic cellular proliferation composed exclusively of multinucleated giant cells or a predominantly giant cell carcinoma (Figure 5A,B) or associated with a conventional non-small cell carcinoma like adenocarcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma. The giant cell carcinoma may show giant cells of the syncytiotrophoblastic, osteoclastic, or null cell type. The giant cell carcinomas of the null cell type characteristically show a prominent inflammatory background and giant cells engulfing inflammatory cells (emperipolesis) (Figure 6A,B). The tumors composed of osteoclast-like giant cells show giant cells like those described in bone tumors (Figure 7A,B).

Figure 5. (A) Predominantly giant cell carcinoma; (B) Marked atypia and numerous multinucleated malignant giant cells.

Figure 6. (A) Giant cell carcinoma, null cell type, note the inflammatory background; (B) Malignant giant cells with inflammatory cells and focal emperipolesis.

Figure 7. (A) Carcinoma associated with osteoclast giant cells; (B) Osteoclast giant cells like those in bone tumors.

Immunohistochemical Features

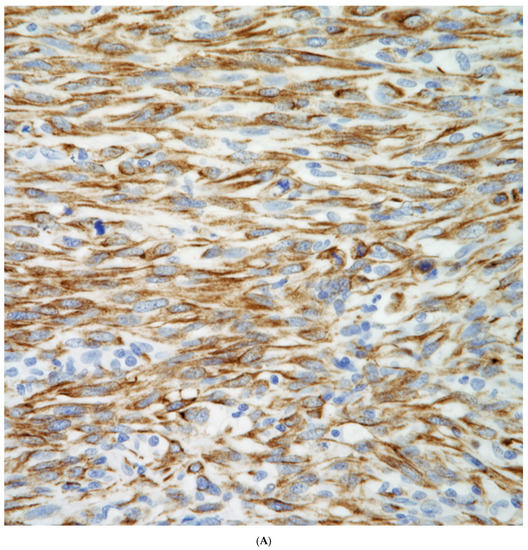

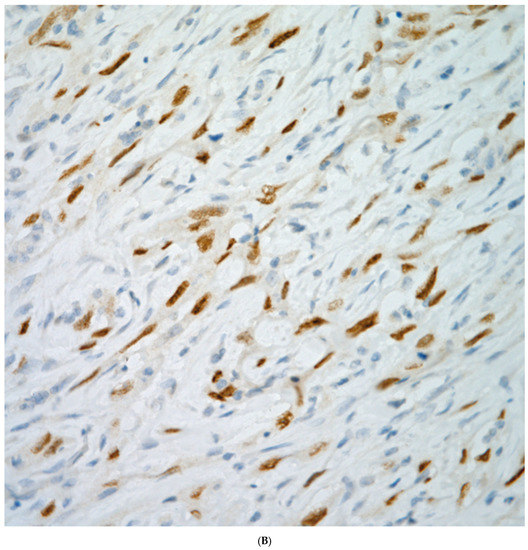

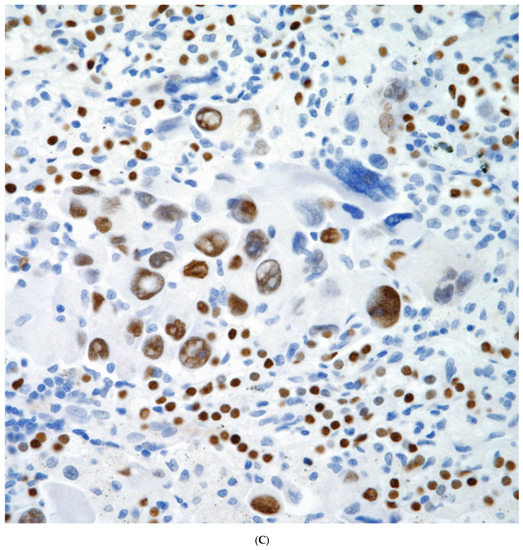

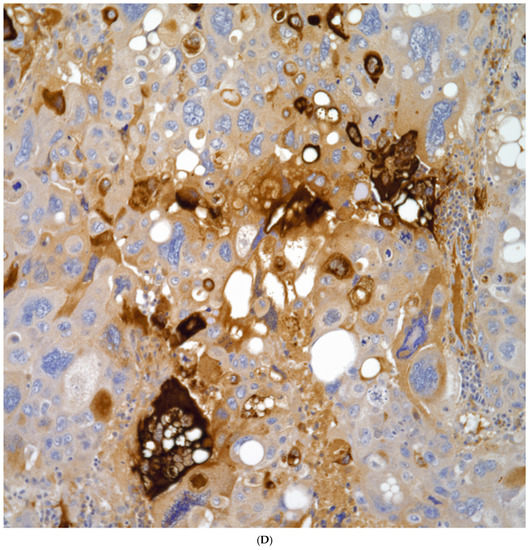

The use of conventional pneumocytic and squamous markers such as TTF-1, Napsin A, p40, p63, and keratin 5/6 are commonly used in the evaluation of non-small cell carcinomas. These markers also play an important role in the evaluation of the spindle cell component as it has been demonstrated that the spindle cells may show positive staining for either pneumocytic or squamous markers, which will provide a more accurate classification of these tumors (Figure 8A–D). On the other hand, the use of other markers such as human chorionic gonadotrophin, cytokeratin, CD68, cathepsin, and histone H3 may provide important information in the type of giant cells present, thus a more accurate classification of these tumors.

Figure 8. (A) Keratin positive in a sarcomatoid carcinoma; (B) p40 positive in a sarcomatoid squamous cell carcinoma, (C) TTF-1 positive in a pleomorphic carcinoma; (D) HCG positive in multinucleated giant cells.

The larger single most important issue regarding immunohistochemical analysis is the type of tissue for evaluation. In daily practice that may pose significant challenges as the only tissue may be a small biopsy, which inevitably will have limitations, mainly if the tissue is negative for all specific markers (squamous or pneumocytic). In such cases, the term “sarcomatoid” carcinoma may become a default diagnosis. However, every effort should be made to correlate that biopsy with a possible surgical resection in which more tissue becomes available. Additionally, important to mention is that diagnostic surgical pathologists are limited to the number of possible stains that may be available for proper classification –TTF-1, Napsin A, p63, p40, keratin 5/6 are among the most commonly used and recommended for diagnostic purposes, but it is also known that some of those stains may also show cross-reactivity, e.g., p63 commonly used as squamous marker is positive in about 25% of adenocarcinomas. However, in such cases at least one can state that there is some immunohistochemical evidence of differentiation towards what the morphology may dictate. Also the current definition of these tumors at the end may play a role in how tumors are classified.

3.4. Molecular Features

The evaluation of tumors composed exclusively of spindle or giant cells is still a work in progress. One important aspect is that these tumors are not very common in comparison to the conventional non-small cell carcinomas. In addition, when these tumors are evaluated, usually it is the non-small cell component that is associated with the spindle cell or giant cell carcinoma. Therefore, there is existing bias in their evaluation. However, this issue has been highlighted by some authors about the need to properly analyze these types of tumors [35,36][10][11]. Currently, some studies on sarcomatoid carcinoma have been performed [37,38,39,40,41,42][12][13][14][15][16][17] showing some variations in the molecular analysis such as MET exon 14 skipping mutations. However, the issue of giant cell carcinomas remains unknown as such a component has eluded a more comprehensive analysis.

In addition, other molecular features that have been encountered in sarcomatoid carcinomas include higher prevalence of TP53, KRAS, PIK3CA, MET, NOTCH, STK11, and RB1. However, the correlation that has not taken place is whether those tumors studied could have been classified as spindle cell squamous cell carcinomas, spindle cell adenocarcinomas, or just spindle large cell carcinomas. Such analysis could explain the results in some of these cases and in addition provide important information to oncologists for the possible treatment of such patients. One additional issue to highlight is whether the material available was part of a small biopsy; whether it came from a resected specimen, and whether specific immunohistochemical markers were performed and the results of them. These are important issues to address so that proper classification is provided rather than the general term of “sarcomatoid” carcinoma. Reserachers should be aware of the limitations that exist in biopsy interpretation. However, in such cases, if a surgical resection takes place, it may be possible to correlate the biopsy, the resected material, and the molecular features that may have become available in case the biopsy was the tissue that was used for molecular testing. Having that correlation may provide important information that can be used for prospective studies and analysis. Currently, due to the definition provided for these tumors, it is likely that molecular studies may also show some incomplete information.

References

- Humphrey, P.; Scroggs, M.; Roggli, V.; Shelburne, J.D. Pulmonary carcinomas with sarcomatoid element: An immunohistochemical and ultrastructural analysis. Hum. Pathol. 1988, 19, 155–165.

- Ro, J.; Chen, J.; Lee, J.; Sahin, A.A.; Ordóñez, N.G.; Ayala, A.G. Sarcomatoid carcinoma of the lung: Immunohistochemical and ultrastructural studies of 14 cases. Cancer 1992, 69, 376–386.

- Matsui, K.; Kitawa, M. Spindle cell carcinoma of the lug: A clinicopathologic study of three cases. Cancer 1991, 67, 2361–2367.

- Battifora, H. Spindle cell carcinoma: Ultrastructural evidence of squamous origin and collagen production by tumor cells. Cancer 1976, 37, 2275–2282.

- Lichtiger, B.; Mackay, B.; Tessmer, C. Spindle cell variant of squamous carcinoma: Light and electron microscopic study of 13 cases. Cancer 1970, 26, 1311–1320.

- Fishback, N.F.; Travis, W.D.; Moran, C.A.; Guinee, D.G.; McCarthy, W.F.; Koss, M.N. Pleomorphic (spindle/giant cell) carcinoma of the lung. Cancer 1994, 73, 2936–2945.

- Weissferdt, A.; Kalhor, N.; Correa, A.M.; Moran, C.A. “Sarcomatoid” carcinomas of the lung: A clinicopathological study of 86 cases with a new perspective on tumor classification. Hum. Pathol. 2017, 63, 14–26.

- Weissferdt, A.; Moran, C.A. Primary giant cell carcinomas of the lung: A clinicopathological and immunohistochemical analysis of seven cases. Histopathology 2016, 68, 680–685.

- Lindholm, K.E.; Kalhor, N.; Moran, C.A. Osteoclast-like giant cell-rich carcinomas of the lung: A clinicopathological, immunohistochemical, and molecular study of 3 cases. Hum. Pathol. 2019, 85, 168–173.

- Sharma, M. Pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinoma. Int. J. Med. Dent. Sci. 2018, 7, 1684–1685.

- Pécuchet, N.; Vieira, T.; Rabbe, N.; Antoine, M.; Blons, H.; Cadranel, J.; Laurent-Puig, P.; Wislez, M. Molecular classification of pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinomas suggests new therapeutic opportunities. Oncology 2017, 28, 1597–1604.

- Yang, Z.; Xu, J.; Li, L.; Li, R.; Wang, Y.; Tian, Y.; Guo, W.; Wang, Z.; Tan, F.; Ying, J.; et al. Integrated molecular characterization reveals potential therapeutic strategies for pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinoma. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4878.

- Liu, X.; Jia, Y.; Stoopler, M.B.; Shen, Y.; Cheng, H.; Chen, J.; Mansukhani, M.; Koul, S.; Halmos, B.; Borczuk, A.C. Next-generation sequencing of pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinoma reveals high frequency of actionable MET gene mutations. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 794–802.

- Terra, S.B.; Jang, J.S.; Bi, L.; Kipp, B.R.; Jen, J.; Yi, E.S.; Boland, J.M. Molecular characterization of pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinoma: Analysis of 33 cases. Mod. Pathol. 2016, 29, 824–831.

- Lin, Y.; Yang, H.; Cai, Q.; Wang, D.; Rao, H.; Lin, S.; Long, H.; Fu, J.; Zhang, L.; Lin, P.; et al. Characteristics and prognostic analysis of 69 patients with pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinoma. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 39, 215–222.

- Fallet, V.; Saffroy, R.; Girard, N.; Mazieres, J.; Lantuejoul, S.; Vieira, T.; Rouquette, I.; Thivolet-Bejui, F.; Ung, M.; Poulot, V.; et al. High-throughput somatic mutation profiling in pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinomas using the LungCartaTM Panel: Exploring therapeutic targets. Ann. Oncol. 2015, 26, 1748–1753.

- Nakagomi, T.; Goto, T.; Hirotsu, Y.; Shikata, D.; Yokoyama, Y.; Higuchi, R.; Amemiya, K.; Okimoto, K.; Oyama, T.; Mochizuki, H.; et al. New therapeutic targets for pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinomas based on their genomic and phylogenetic profiles. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 10635–10640.

More