This research assessed alternatives for air Heating, VACentilation, and Air Conditioning (HVAC) systems to minimize Sick Building Syndrome and improve air quality while considering international programs/standards. For this purpose, an alternative technology known as desiccant wheels was studied by analyzing their principles and types when the existing selection software for these types of equipment was performed. In addition, energy-efficiency programs worldwide and in the Brazilian context were analyzed while aiming at implementing strategies in which desiccant wheels are appropriate. Finally, some examples of commercial software for desiccant wheels were compared to identify the different tools available in the air conditioning market.

- dehumidification

- desiccant wheels

- air quality

- air conditioning systems

1. Background

2. Types of Desiccant Dehumidification Systems

2.1. Spray Drying Tower

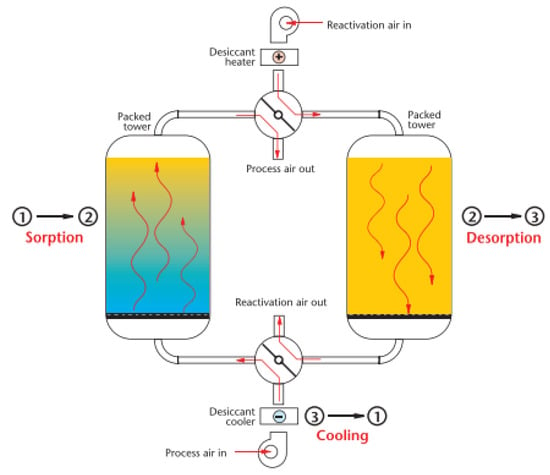

The spray drying tower has two tanks corresponding to the condenser and the regenerator. In this system, the humid air enters the segment of the condenser and passes through a saline fog that will capture the humidity of the air while the dry air is inflated for the process. At the bottom of the condenser tank, the saline solution is pumped to the second tank (regenerator), through which the second flow of high-temperature external air passes, causing the saline solution to lose moisture to the regeneration air. Thus, the hygroscopic material returns to the condenser tank [7].2.2. Dual-Tower Desiccant Dryers

2.3. Tray Dryer

2.4. Multi-Belt Dryer

2.5. Desiccant Dehumidifier

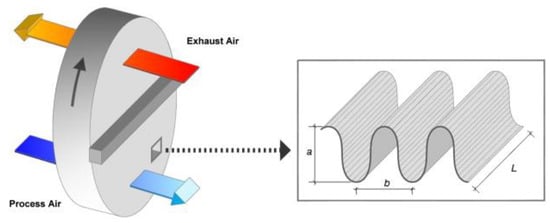

3. Desiccant Dehumidification by Heat-Recovery Wheel

3.1. Enthalpy Wheels

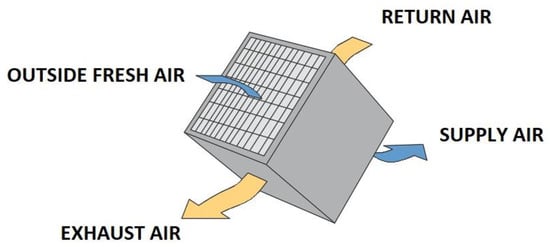

3.2. Cross-Flow Heat Exchangers

4. Software for Selecting Desiccant Wheels

| Novel Aire | Munters | Rotor Source | Puresci | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Input data | ||||

| Process inlet dry bulb temperature | X | X | X | X |

| Absolute humidity entering the process | X | X | X | X |

| Regeneration inlet dry bulb temperature | X | X | X | X |

| Absolute inlet humidity in regeneration | X | X | X | X |

| Dry bulb temperature after heating in regeneration | X | X | X | X |

| Output data | ||||

| Output dry bulb temperature in the process | X | X | X | X |

| Output absolute humidity in the process | X | X | X | X |

| Dry bulb temperature after regeneration output | X | X | X | X |

| Output absolute humidity at regeneration output | X | X | X | X |

| Moisture removal charge | X | X | ||

References

- Munters Munters’ Desiccant Rotor—Industrial Dehumidification at Its Best. Available online: https://www.munters.com/en/about-us/history-of-munters/history-news2/munters-desiccant-rotor--industrial-dehumidification-at-its-best/ (accessed on 11 July 2022).

- Kent, R. Services. In Energy Management in Plastics Processing; Kent, R., Ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2018; pp. 105–210. ISBN 978-0-08-102507-9.

- Narayanan, R. Heat-Driven Cooling Technologies. In Clean Energy for Sustainable Development; Rasul, M.G., Azad, A.K., Sharma, S., Eds.; Academic Press: Oxford, UK, 2017; pp. 191–212. ISBN 978-0-12-805423-9.

- Rambhad, K.S.; Walke, P.V.; Tidke, D.J. Solid Desiccant Dehumidification and Regeneration Methods—A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 59, 73–83.

- Guan, B.; Liu, X.; Zhang, T. Investigation of a Compact Hybrid Liquid-Desiccant Air-Conditioning System for Return Air Dehumidification. Build. Environ. 2021, 187, 107420.

- ASHRAE. 2019 ASHRAE Handbook_HVAC Applications CH35.Pdf; ASHRAE: Orlando, FL, USA, 2019; ISBN 9781947192133.

- Kojok, F.; Fardoun, F.; Younes, R.; Outbib, R. Hybrid Cooling Systems: A Review and an Optimized Selection Scheme. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 65, 57–80.

- Ling-Chin, J.; Bao, H.; Ma, Z.; Roskilly, W.T. State-of-the-Art Technologies on Low-Grade Heat Recovery and Utilization in Industry. In Energy Conversion—Current Technologies and Future Trends; Al-Bahadly, I.H., Ed.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Italy, 2018; pp. 55–74. ISBN 978-1-78984-905-9.

- Munters. Dehumidificaion Handbook, 3rd ed.; Munters Corporation, Ed.; Munters Corporation Marketing Department: Amesbury, MA, USA, 2019; ISBN 2013206534.

- Mujumdar, A.S.; Huang, L.-X.; Chen, X.D. An Overview of the Recent Advances in Spray-Drying. Dairy Sci. Technol. 2010, 90, 211–224.

- Zhang, H.; Pang, B.; Kang, S.; Fu, J.; Tang, P.; Chang, J.; Li, J.; Li, Z.; Deng, S. The Influence of Feedstock Stacking Shape on the Drying Performance of Conveyor Belt Dryer. Heat Mass Transf. 2022, 58, 157–170.

- Li, X. Analysis on the Utilization of Temperature and Humidity Independent Control Air-Conditioning System with Different Fresh-Air Handling Methods. Procedia Eng. 2017, 205, 71–78.

- Chen, T.; Norford, L. Energy Performance of Next-Generation Dedicated Outdoor Air Cooling Systems in Low-Energy Building Operations. Energy Build. 2020, 209, 109677.

- Gado, M.G.; Nasser, M.; Hassan, A.A.; Hassan, H. Adsorption-Based Atmospheric Water Harvesting Powered by Solar Energy: Comprehensive Review on Desiccant Materials and Systems. Process. Saf. Environ. Prot. 2022, 160, 166–183.

- Nizovtsev, M.I.; Borodulin, V.Y.; Letushko, V.N. Influence of Condensation on the Efficiency of Regenerative Heat Exchanger for Ventilation. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2017, 111, 997–1007.

- Calautit, J.K.; O’Connor, D.; Tien, P.W.; Wei, S.; Pantua, C.A.J.; Hughes, B. Development of a Natural Ventilation Windcatcher with Passive Heat Recovery Wheel for Mild-Cold Climates: CFD and Experimental Analysis. Renew. Energy 2020, 160, 465–482.

- Xu, Q.; Riffat, S.; Zhang, S. Review of Heat Recovery Technologies for Building Applications. Energies 2019, 12, 1285.

- Men, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhang, T. A Review of Boiler Waste Heat Recovery Technologies in the Medium-Low Temperature Range. Energy 2021, 237, 121560.

- Herath, H.M.D.P.; Wickramasinghe, M.D.A.; Polgolla, A.M.C.K.; Jayasena, A.S.; Ranasinghe, R.A.C.P.; Wijewardane, M.A. Applicability of Rotary Thermal Wheels to Hot and Humid Climates. Energy Rep. 2020, 6, 539–544.

- Liu, Z.; Li, W.; Chen, Y.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, L. Review of Energy Conservation Technologies for Fresh Air Supply in Zero Energy Buildings. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2019, 148, 544–556.

- Jani, D.B.; Mishra, M.; Sahoo, P.K. Solid Desiccant Air Conditioning—A State of the Art Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 60, 1451–1469.

- Altomonte, S.; Schiavon, S.; Kent, M.G.; Brager, G. Indoor Environmental Quality and Occupant Satisfaction in Green-Certified Buildings. Build. Res. Inf. 2019, 47, 255–274.

- Zender–Świercz, E. A Review of Heat Recovery in Ventilation. Energies 2021, 14, 1759.

- Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Huang, Q.; Cui, Y. Experimental and Theoretical Investigation of Cross-Flow Heat Transfer Equipment for Air Energy High Efficient Utilization. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2016, 98, 1231–1240.

- Hye-Cho, J.; Cheon, S.-Y.; Jeong, J.-W. Development of empirical models to predict latent heat exchange performance for hollow fiber membrane-based ventilation system. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2022, 213, 118686.

- Silaipillayarputhur, K.; Al-Mughanam, T. Performance of Pure Crossflow Heat Exchanger in Sensible Heat Transfer Application. Energies 2021, 14, 5489.

- Nasif, M.S. Air-to-Air Fixed Plate Energy Recovery Heat Exchangers for Building’s HVAC Systems. In Sustainable Thermal Power Resources through Future Engineering; Sulaiman, S.A., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 63–71. ISBN 9789811329685.

- Santos, S.M.D.; Sphaier, L.A. Transient Formulation for Evaluating Convective Coefficients in Regenerative Exchangers with Hygroscopic Channels. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2020, 116, 104691.

- Sphaier, L.A.; Worek, W.M. Parametric Analysis of Heat and Mass Transfer Regenerators Using a Generalized Effectiveness-NTU Method. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2009, 52, 2265–2272.

- Sphaier, L.A.; Worek, W.M. Numerical Solution of Periodic Heat and Mass Transfer with Adsorption in Regenerators: Analysis and Optimization. Numer. Heat Transf. A Appl. 2008, 53, 1133–1155.

- Sphaier, L.A.; Worek, W.M. The Effect of Axial Diffusion in Desiccant and Enthalpy Wheels. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2006, 49, 1412–1419.