Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Camila Xu and Version 1 by Ana Checa Ros.

Resolvins (Rvs), Maresins (MaRs), Protectins (PDs), and Lipoxins (LXs), belong to a large group of molecules known as The Specialized Pro-resolving Lipid Mediators (SPMs). These compounds have been well-characterized since their identification as potent modulators of the immune response and for their effects on inflammation resolution. Furthermore, they have a potential effect on anti-tumor immunity.

- cancer

- carcinogenesis

- chronic inflammation

- specialized pro-resolving lipid mediators

- bioactive lipids

1. Origin, Biosynthesis, and Classification

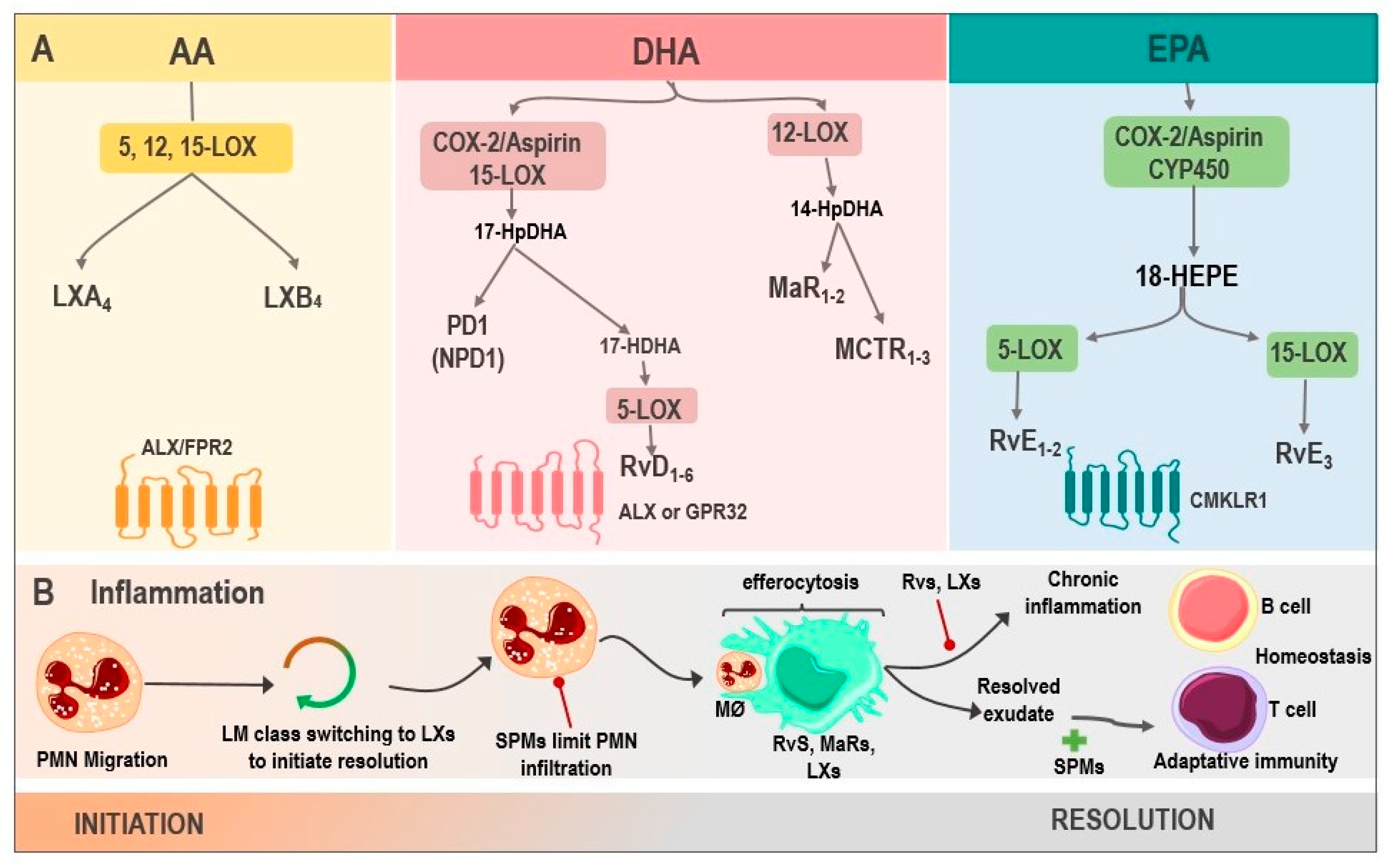

For decades, immunopathology has faced the challenge of elucidating the mechanisms of associating chronic disorders with inflammation. Within the pleiad of molecular pathways, mediators, receptors, and metabolites, the resolution of inflammation has been a well-recognized process where complex signaling downregulates the immune cascade once the noxious stimulus is eliminated by both innate and adaptative immune responses and, as a result, the recovering of tissue homeostasis occurs [34][1]. Upon this premise, Serhan et al. [35][2] were the first to identify lipid metabolism products involved in this process by describing a family of bioactive compounds later coined SPMs (Figure 1), a group of molecules derived from omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids (ω-6 PUFAs) metabolism, such as arachidonic acid (AA; 20:4n − 6), and omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (ω-3 PUFAs), such as eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA; 20:5n − 3) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA; 22:6n − 3) via COX/LOX pathway [36][3].

Figure 1. Biosynthesis of SPMs and their actions in inflammation. (A) LX are generated from AA via 5, 12, 15-LOX, resulting in LXA4 and LXB4, whose receptor is ALX/FPR2. DHA, via COX-2/Aspirin as well as via 15-LOX, produces 17-HpDHA, which can be metabolized into PD1 or NPD1 and is synthesized in the nervous system or into 17-HDHA, generating RvD1-6 via 5-LOX, with activity on ALX or GPR32. Another DHA pathway is through 12-LOX, where MaR1-2 and MCTRs are produced. Finally, the biosynthesis of RvE1-3 derives from EPA, by the enzymes COX-2/Aspirin or CYP450, being their receptor CMKLR1. (B). SPMs in inflammation: the inflammatory microenvironment starts with PMN migration. Afterward, the change of pro-inflammatory LMs into pro-resolving ones occurs with the initial synthesis of LXs. PMN infiltration increases, and SPMs act at this point, reducing this influx. Moreover, the efferocytosis by MØ is stimulated and improved by Rvs, MaRs, and LXs. Adaptive immunity, stimulated by SPMs, participates during the final phase of resolution. However, whenever there is an exaggerated and chronic inflammatory response, it leads to chronic inflammation, inhibited by Rvs, and LXs. Abbreviations: SPMs: specialized pro-resolving mediator; AA: Arachidonic acid; LXs: Lipoxins; LOX: lipoxygenase; LXA4: lipoxin A4; LXB4: lipoxin B4; ALX: G protein-coupled lipoxin A4 receptor; formyl peptide receptor; DHA: docosahexaenoic acid; COX-2/Aspirin: Aspirin acetylates cyclooxygenase-2; 17-HpDHA: 17-hydroperoxyDHA; PD1: Protectin 1; NPD1: neuroprotectin 1; 17-HDHA: 17-hydroxy-DHA; Rvs: D1-6-series resolvins; GPR32: G protein-coupled receptor; MaRs1-2: Maresins 1-2; MCTR: maresin conjugates in tissue regeneration; RvE1-3: E1-3-series resolvins; EPA: Eicosapentaenoic acid; CYP450: cytochrome P450; CMKLR1: chemokine-like receptor 1; PMN: polymorphonuclear neutrophil; LM: lipid mediators; and MØ: macrophages.

SPMs belongs to G protein-coupled receptors ligands [37][4], and their critical role in regulating inflammation resolution has been widely documented, establishing that excessive or uncontrolled inflammation is tightly linked to a disbalance in their synthesis. Therefore, it is vital to understand every SPMs family’s role in the framework of acute and chronic inflammation [38][5].

2. Resolvins

Rvs are unique molecules synthesized from DHA and EPA by polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMN) and macrophages during the resolution of inflammation to counter-regulate pro-inflammatory activity and promote efferocytosis [39][6]. In this regard, five resolvins families have been identified to date: the resolvin Ds (RvDs) 22-carbon DHA metabolites; the resolvin Es (RvEs) 20-carbon EPA metabolites; the resolvin Dn-6DPA (RvDsn-6DPA), a group of metabolites derived from the Osbond acid; the resolvin Dn-3DPA (RvDn-3DPA), which come from clupanodonic acid metabolism; and the resolvin Ts (RvTs), a clupanodonic acid metabolite [40][7].

RvDs are poly-hydroxyl metabolites of DHA, and to date, six RvDs (RvsD1-6), which vary in the number, position, and chirality of their hydroxyl residues and the position and cis-trans isomerism of their six double bonds, have been described [40][7]. Thus far, these variants have been identified in PMN and macrophages inflammatory exudates with a variety of allylic–epoxide intermediaries containing RvD1-2 at the start of the resolution, and later, RvD3-4 [41][8]. Furthermore, to carry out their functions, RvDs are ligands of G protein-coupled receptors (GPCR), such as ALX/FPR2, GPR18, GPR32, TRPA1, and the TRPV1 receptor [39][6].

On the other hand, EPA-derived E-series Rvs (RvE) includes four primary bioactive mediators (RvE1, RvE2, RvE3, and18-HEPE), synthesized by 5-LOX and 15-LOX in PMN and macrophages. These molecules exert their functions by Chem23, BLT1, and TRPV1 receptor-binding [42][9]. It has been reported that RvE1 regulates leukocyte adhesion molecules expression, ADP-dependent platelet activation, and PMN apoptosis stimulation [43][10]. In addition, RvE1, along with RvE2, increases IL-10 synthesis and phagocytosis [44][11]. Moreover, it is relevant to highlight the properties of RvE3 in the decrease in PMN and 18-HEPE production. These properties have been associated with a cardioprotective function in several studies since RvE1 protected against reperfusion injury in this open-chest rat model of ischemia–reperfusion [45][12] and protects against doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity by inhibiting oxidative stress, autophagy, and apoptosis by targeting AKT/mTOR signaling [46][13].

13-series Rvs (RvT) are also derived from ω-3 PUFAs, from docosapentaenoic acid (DPA), and synthesized by COX-2 during the resolution of acute inflammation. This family includes four mediators, RvT1, RvT2, RvT3, and RvT4 [24][14]. In this vein, Dalli et al. [47][15] described the anti-inflammatory role of RvsT1-4 in mice endothelial cells and neutrophil co-cultures during E. coli infection, demonstrating a protective response through the regulation of inflammation. Other important resolvins are the RvDsn-6DPA, a metabolite of the osbond acids, and resolvin Dn-3DPA (RvDn-3DPA), a clupanodonic acid metabolite. On the other hand, AT-RvDs are synthesized by non-native COX-2 (drug-modified cyclooxygenase 2) to form 17 (R)-hydroxyl residue named aspirin-triggered RvDs (AT-RvDs).

3. Lipoxins

LXs, synthesized in platelets and leukocytes from AA, are another group of bioactive lipids capable of carrying out a wide variety of functions. These include regulating the synthesis of pro-inflammatory cytokines, inhibiting angiogenesis, and reprogramming M2 macrophages by binding to ALX/FPR2 and GPR32 receptors [48][16]. Their variants, LXA4 derived from AA and aspirin-triggered LXA4 (ATL), are generated by 15-LOX. These compounds have protective anti-inflammatory actions on various physiologic and pathophysiologic processes as endogenous lipids acting in the resolution phase upon an inflammatory response [49][17], playing an essential role in the tumor microenvironment (TME) and cancer pathogenesis in several neoplasms, such as pancreatic, liver and colon cancer, melanoma, leukemia, and Kaposi’s sarcoma [50][18]. The healing role of these molecules has been widely demonstrated in preclinical studies. For instance, Madi et al. [51][19] evaluated LXA4 administration to mice with gastric ulcers, resulting in a significant histopathologic and immunohistochemical improvement in the gastric mucosa.

4. Maresins

MaRs, also called macrophage mediators in resolving inflammation, are an SPMs family synthesized from DHA by the 12-LOX enzyme. These have functions related to phagocytes, such as the inhibition of neutrophil recruitment and macrophage efferocytosis stimulation [52][20]. Moreover, they can negatively regulate the synthesis of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α, to induce the resolution of inflammation and tissue regeneration [53][21]. The members of this family are maresin 1 (MaR1), maresin 2 (MaR2), and maresin conjugates in tissue regeneration (MCTR1-3). These compounds are synthesized by macrophages via lipooxygenation at the carbon-14 position with molecular oxygen insertion. Finally, MaRs action is achieved through BLT1 and TRPV1 receptors binding [54][22].

5. Protectins

The last group of SPMs are PDs, which, just like MaRs and RvD, are biosynthesized from DHA by the action of 15-LOX during the resolution of inflammation [55][23]. Protectin D1 (PD1) is the first and best-studied member of this family. This compound is synthesized by various cells, including leukocytes, such as PMN, eosinophils, and macrophages [56][24]. PD1 is also known as neuroprotectin D1 (NPD1) when synthesized in neural systems, and it has a protective action in the brain, retina, and in pain modulation [57][25]. Like other SPM family members, NPD1 exerts potent anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic/neuroprotective biological activities [58,59][26][27]. NPD1 actions in the central nervous system (CNS) are mediated by its interaction with the parkin-associated endothelin-like receptor (Pael-R), also known as GPR37, widely expressed in glial cells, such as astrocytes and oligodendrocytes [59][27].

Other neuroprotective structurally related agents exhibiting similar activity are PDX (10R, 17S-dihydroxy-4Z, 7Z, 11E, 13Z, 15E, 19Z-DHA); 20-hydroxy-PD1 (10R, 17S, 20-trihydroxy-4Z, 7Z, 11E, 13E, 15Z, 19Z-DHA); and 10-epi-PD1 (10R, 17S-Dihydroxy-4Z, 7Z, 11E, 13E, 15Z, 19Z-DHA) [60,61][28][29]. The beneficial effect of these anti-inflammatory mediators was reported by Sheets et al. [62][30], who demonstrated both a laser-induced choroidal neuro-vascularisation attenuation and microglia cells elongating in mouse eyes treated with NPD1. In addition, evidence in aged-mice models indicates that NPD1 is able to diminish post-operative delirium (POD). Post-surgical administration of NPD1 decreased IL-6 and TNF-α expression systemically as well as in the hippocampus and pre-frontal cortex; moreover, this SPM maintains the integrity of the blood–brain barrier (BBB) and induces macrophages polarization into an M2 phenotype, limiting neuroinflammation and cognitive decay [63][31].

References

- Basil, M.C.; Levy, B.D. Specialized Pro-Resolving Mediators: Endogenous Regulators of Infection and Inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016, 16, 51–67.

- Serhan, C.N. Lipoxin Biosynthesis and Its Impact in Inflammatory and Vascular Events. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1994, 1212, 1–25.

- Nicolaou, A.; Mauro, C.; Urquhart, P.; Marelli-Berg, F. Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid-Derived Lipid Mediators and T Cell Function. Front. Immunol. 2014, 5, 75.

- Fattori, V.; Zaninelli, T.H.; Rasquel-Oliveira, F.S.; Casagrande, R.; Verri, W.A. Specialized Pro-Resolving Lipid Mediators: A New Class of Non-Immunosuppressive and Non-Opioid Analgesic Drugs. Pharmacol. Res. 2020, 151, 104549.

- Greene, E.R.; Huang, S.; Serhan, C.N.; Panigrahy, D. Regulation of Inflammation in Cancer by Eicosanoids. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2011, 96, 27–36.

- Moro, K.; Nagahashi, M.; Ramanathan, R.; Takabe, K.; Wakai, T. Resolvins and Omega Three Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids: Clinical Implications in Inflammatory Diseases and Cancer. World J. Clin. Cases 2016, 4, 155–164.

- Serhan, C.N.; Levy, B.D. Resolvins in Inflammation: Emergence of the pro-Resolving Superfamily of Mediators. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 128, 2657–2669.

- Ye, Y.; Scheff, N.N.; Bernabé, D.; Salvo, E.; Ono, K.; Liu, C.; Veeramachaneni, R.; Viet, C.T.; Viet, D.T.; Dolan, J.C.; et al. Anti-Cancer and Analgesic Effects of Resolvin D2 in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Neuropharmacology 2018, 139, 182–193.

- Giordano, C.; Plastina, P.; Barone, I.; Catalano, S.; Bonofiglio, D. N-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid Amides: New Avenues in the Prevention and Treatment of Breast Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2279.

- D’Archivio, M.; Scazzocchio, B.; Vari, R.; Santangelo, C.; Giovannini, C.; Masella, R. Recent Evidence on the Role of Dietary PUFAs in Cancer Development and Prevention. Curr. Med. Chem. 2018, 25, 1818–1836.

- Serhan, C.N.; Yacoubian, S.; Yang, R. Anti-Inflammatory and Proresolving Lipid Mediators. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2008, 3, 279–312.

- Keyes, K.T.; Ye, Y.; Lin, Y.; Zhang, C.; Perez-Polo, J.R.; Gjorstrup, P.; Birnbaum, Y. Resolvin E1 Protects the Rat Heart against Reperfusion Injury. Am. J. Physiol.-Heart Circ. Physiol. 2010, 299, H153–H164.

- Zhang, J.; Wang, M.; Ding, W.; Zhao, M.; Ye, J.; Xu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Ye, D.; Li, D.; Liu, J.; et al. Resolvin E1 Protects against Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity by Inhibiting Oxidative Stress, Autophagy and Apoptosis by Targeting AKT/MTOR Signaling. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2020, 180, 114188.

- Prevete, N.; Liotti, F.; Amoresano, A.; Pucci, P.; de Paulis, A.; Melillo, R.M. New Perspectives in Cancer: Modulation of Lipid Metabolism and Inflammation Resolution. Pharmacol. Res. 2018, 128, 80–87.

- Dalli, J.; Chiang, N.; Serhan, C.N. Elucidation of Novel 13-Series Resolvins That Increase with Atorvastatin and Clear Infections. Nat. Med. 2015, 21, 1071–1075.

- Guo, Y.; Dong, C.; Tang, J.; Deng, X.; Wang, G.; Wang, W.; Xu, H. Lipoxin A4 Alleviates Cerebral Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury through up-Regulating Nrf2. J. Neurosurg. Sci. 2018, 62, 225–226.

- Wang, Z.; Cheng, Q.; Tang, K.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, S.; Zhang, H.; Ye, D.; Huang, B. Lipid Mediator Lipoxin A4 Inhibits Tumor Growth by Targeting IL-10-Producing Regulatory B (Breg) Cells. Cancer Lett. 2015, 364, 118–124.

- Chandrasekharan, J.A.; Huang, X.M.; Hwang, A.C.; Sharma-Walia, N. Altering the Anti-Inflammatory Lipoxin Microenvironment: A New Insight into Kaposi’s Sarcoma-Associated Herpesvirus Pathogenesis. J. Virol. 2016, 90, 11020–11031.

- Madi, N.M.; Ibrahim, R.R.; Alghazaly, G.M.; Marea, K.E.; El-Saka, M.H. The Prospective Curative Role of Lipoxin A4 in Induced Gastric Ulcer in Rats: Possible Involvement of Mitochondrial Dynamics Signaling Pathway. IUBMB Life 2020, 72, 1379–1392.

- Hwang, S.-M.; Chung, G.; Kim, Y.H.; Park, C.-K. The Role of Maresins in Inflammatory Pain: Function of Macrophages in Wound Regeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5849.

- Hong, S.; Lu, Y.; Morita, M.; Saito, S.; Kobayashi, Y.; Jun, B.; Bazan, N.G.; Xu, X.; Wang, Y. Stereoselective Synthesis of Maresin-like Lipid Mediators. Synlett 2019, 30, 343–347.

- Tang, S.; Wan, M.; Huang, W.; Stanton, R.C.; Xu, Y. Maresins: Specialized Proresolving Lipid Mediators and Their Potential Role in Inflammatory-Related Diseases. Mediat. Inflamm. 2018, 2018, 2380319.

- Bazan, N.G. The Docosanoid Neuroprotectin D1 Induces Homeostatic Regulation of Neuroinflammation and Cell Survival. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids 2013, 88, 127–129.

- Bennett, M.; Gilroy, D.W. Lipid Mediators in Inflammation. Microbiol. Spectr. 2016, 4.

- Duvall, M.G.; Levy, B.D. DHA- and EPA-Derived Resolvins, Protectins, and Maresins in Airway Inflammation. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2016, 785, 144–155.

- Hong, S.; Gronert, K.; Devchand, P.R.; Moussignac, R.-L.; Serhan, C.N. Novel Docosatrienes and 17S-Resolvins Generated from Docosahexaenoic Acid in Murine Brain, Human Blood, and Glial Cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 14677–14687.

- Bazan, N.G. Omega-3 Fatty Acids, pro-Inflammatory Signaling and Neuroprotection. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2007, 10, 136–141.

- Shinohara, M.; Mirakaj, V.; Serhan, C.N. Functional Metabolomics Reveals Novel Active Products in the DHA Metabolome. Front. Immunol. 2012, 3, 81.

- Balas, L.; Durand, T. Dihydroxylated E,E,Z-Docosatrienes. An Overview of Their Synthesis and Biological Significance. Prog. Lipid Res. 2016, 61, 1–18.

- Sheets, K.G.; Jun, B.; Zhou, Y.; Zhu, M.; Petasis, N.A.; Gordon, W.C.; Bazan, N.G. Microglial Ramification and Redistribution Concomitant with the Attenuation of Choroidal Neovascularization by Neuroprotectin D1. Mol. Vis. 2013, 19, 1747–1759.

- Zhou, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, X.; Li, K.; Chen, L.; Zhang, Z.; Peng, M. Neuroprotectin D1 Protects Against Postoperative Delirium-Like Behavior in Aged Mice. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2020, 12, 582674.

More