The chemical group comprising polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) has received prolonged evaluation and scrutiny in the past several decades. PAHs are ubiquitous carcinogenic pollutants and pose a significant threat to human health through their environmental prevalence and distribution. Regardless of their origin, natural or anthropogenic, PAHs generally stem from the incomplete combustion of organic materials. Dietary intake, one of the main routes of human exposure to PAHs, is modulated by pre-existing food contamination (air, water, soil) and their formation and accumulation during food processing. To this end, processing techniques and cooking options entailing thermal treatment carry additional weight in determining the PAH levels in the final product.

- polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons

- occurrence

- processed food

- cooking procedures

1. Introduction

2. PAH Sample Pretreatment in Food and Quantitative Analysis

Sample preparation requires comprehensive extraction followed by purification before detection [26], entailing consistent improvement, as well as alternative approaches [2]. To provide repeatable data and satisfy legal criteria, proper sample preparation is necessary. Taking into account the complexity of food matrices, as well as the trace quantities of PAH molecules in comparison to other constituents, sample pretreatment translates into laborious and time-consuming tasks [15][27][28][15,27,28]. The most common PAH extraction methods include Soxhlet extraction, ultrasonication, and stirring/agitation [2]. The outcomes of these techniques usually involve large amounts of solvent and significant measurement errors [15][29][15,29]. Given the advancement toward more sensitive and accurate analytical techniques, the development of sample preparation processes has gained increasing attention. Automated equipment, shorter analytical times, greater quality, environmentally friendly processes, and smaller sample sizes are all benefits of technique optimization [25][26][28][25,26,28]. Modern extraction techniques for PAHs in food have achieved popularity through their increased efficiency and include pressurized liquid extraction (PLE), microwave-assisted extraction (MAE), supercritical fluid extraction (SFE), high-temperature distillation (HTD), and fluidized-bed extraction (FBE) [2][13][25][30][2,13,25,30]. The purification step is commonly achieved by column chromatography, gel permeation chromatography (GPC), or solid-phase extraction (SPE), along with dispersive liquid–liquid microextraction (DLLME), solid-phase microextraction (SPME), magnetic solid-phase extraction (MSPE), and QuEChERS [2][13][25][28][2,13,25,28]. The advantages of these techniques include lower cost, less solvent, time savings, and increased yield through selective interaction with the molecules, thus ensuring great extraction performance [30][31][30,31]. The QuEChERS (Quick, Easy, Cheap, Effective, Rugged, and Safe) method was first developed to screen pesticides in diverse food and agricultural products [32]. The original QuEChERS approach is aimed at simplifying the extraction and clean-up steps, as compared to time-consuming and laborious conventional procedures [33]. In recent years, the QuEChERS strategy has been persistently adjusted and systematically employed in routine analytical determinations [13][34][13,34]. Its foundation is based on dispersive solid-phase extraction (dSPE) to remove potentially interfering compounds (fats, pigments, sugars, etc.). Apart from multi-residue pesticide analysis, the method has been successfully implemented in food and environmental matrices to separate various target analytes, including mycotoxins, antibiotics, persistent organic pollutants (POPs), hormones, and PAHs, consistently attaining high selectivity, sensitivity, and specificity [2][13][28][34][2,13,28,34]. In addition to the original unbuffered method involving an optimal 1:4 ratio of the two salts (MgSO4 and NaCl) for partitioning [32][35][32,35], two modified QuEChERS methods were established: (a) the EN official method—BS EN 15662:2008 standard (withdrawn) revised in 2018 [36], employing the addition of a citrate buffer (1 g of trisodium citrate dihydrate and 0.5 g of disodium hydrogen citrate sesquihydrate); (b) the AOAC official method [37], applying the addition of an acetate buffer (1.5 g of sodium acetate) and 6 g of MgSO4 instead of 4 g. In the purification process, MgSO4 is used as a drying agent, whereas a primary secondary amine (PSA) is typically applied as a weak anion exchanger targeting the removal of fatty acids, sugars, organic acids, lipids, sugars, and some pigments [33][34][33,34]. Besides PSA and MgSO4, the major sorbents employed are octadecyl silica (C18), which is able to hold vitamins and minerals and is highly effective in removing fats, and graphitized carbon black (GCB), which is effective in eliminating co-extracted pigments (e.g., carotenoids and chlorophyll) [34]. Other approaches are being steadily explored for improved clean-up efficiency, such as alumina, Florisil®, chitosan, diatomaceous earth, zirconia-based sorbents (Z-Sep and Z-Sep+), Enhanced Matrix Removal-Lipid (EMR-Lipid), LipiFiltr®, ChloroFiltr®, CarbonX, and Cleanert® NANO [26][34][38][26,34,38]. Common analytical approaches for the identification and quantification of PAHs in a wide range of food matrices make use of high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with an ultraviolet (UV) or photo-diode array (PDA) detector and gas chromatography (GC) coupled with a flame ionization detector (FID) [2][15][28][2,15,28]. However, these techniques are exceedingly costly, time-consuming, and labor-intensive and no longer match today’s needs regarding selectivity and sensitivity requirements [15][28][15,28]. In contrast, LC and GC techniques coupled with mass spectrometry (MS) surpass the performance of DAD and FLD methods, being widely used in PAH determination in food matrices [2][13][39][2,13,39]. Official methods employing LC determination include ISO 15302:2007 for benzo[a]pyrene (BaP) (withdrawn), revised in 2017 [40], in crude or refined edible oils and fats using reverse-phase HPLC-FLD; ISO 15753:2006 (withdrawn), revised in 2016 [41], for 15 PAHs in animal and vegetable fats and oils, involving a clean-up on C18 and Florisil cartridges followed by HPLC-FLD; ISO 22959:2009 [42] for 17 PAHs in animal and vegetable fats and oils using LC-LC coupling and on-line donor–acceptor complex chromatography (DACC) and FLD; and CEN/TS 16621:2014 [43] for BaP, benzo(a)anthracene (BaA), chrysene (Chr), and benzo(b)fluoranthene (BbF) in foodstuffs using HPLC-FLD, based on SEC clean-up. Methods for PAH determination employing GC techniques include CSN EN 16619:2015 [44] for BaP, BaA, Chr, and BbF in foodstuffs (extruded wheat flour, smoked fish, dry infant formula, sausage meat, freeze-dried mussels, edible oils, wheat flour) using pressurized liquid extraction (PLE); size exclusion chromatography (SEC) and SPE clean-up, followed by GC-MS; and PD ISO/TR 24054:2019 [45] for 27 PAHs (including 16 EPA) in animal and vegetable fats and oils using LL extraction and silica gel column clean-up, followed by GC-MS. In order to address the increasing need for more precise PAH confirmation, modern LC-MS/MS and GC-MS/MS techniques are being developed in addition to conventional analytical methods [2][26][28][46][2,26,28,46].3. PAH Formation—Mechanistic Features

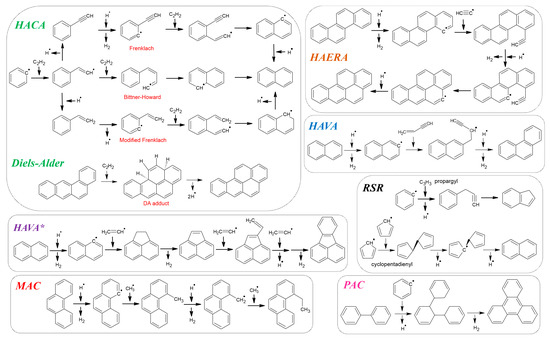

Given their chemical diversity, PAH formation and development occur through a complex set of reactions, mainly through condensation and cyclization from smaller organic molecules; under an array of specific conditions (carbon source, environment), complex approaches entailing PAH structural expansion have been investigated [3][6][47][3,6,47]. As such, the endeavor to provide an appropriate growth model has yielded several representations. The most important types of PAH formation mechanisms identified over the last few decades are based on acetylene addition reactions, vinylacetylene addition reactions, and radical reactions (Figure 3) [11][47][48][49][11,47,48,49].