You're using an outdated browser. Please upgrade to a modern browser for the best experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Yucang Liang and Version 3 by Sirius Huang.

The development of simple, efficient, and economical uranium extraction methods is of great significance for the sustainable development of nuclear energy and the restoration of the ecological environment. Photocatalytic U(VI) extraction technology as a simple, highly efficient, and low-cost strategy, received increasing attention from researchers.

- photocatalysis

- structures

- U(VI) extraction

- mechanism

1. Mechanism of Photocatalytic Uranium Reduction and Identification of Reduction Products

The photocatalytic uranium extraction strategy, as an important technology for uranium resource recovery and ecosystem restoration, widely attracted increasing attention. Only in 2022, there were 67 research articles relevant to the photocatalytic reduction of U(VI), showing a gradually increasing tendency. Current research mainly focuses on how to improve the catalytic efficiency of photocatalysts, while the forms of uranium and the conversion processes were rarely investigated [1][30]. In nature, uranium species mainly exist in uranium mine wastewater and seawater in four valence states: III, IV, V, and IV [2][31]. Among them, U(IV) and U(VI) species are the most stable in a natural water environment, and uranyl ions (UO22+) usually participate in migration and transformation process [3][4][5][16,32,33].

U(VI) can exist as all kinds of U species in aqueous solutions, and the types of U(VI) species change with various acidic and alkaline environments [6][34]. In acidic solutions, U(VI) species mainly exist in the form of UO22+. When pH is higher than 4, UO22+ species decrease, UO2OH+, (UO2)3OH5+, and (UO2)2OH22+ species gradually increase, leading to a complex distribution of uranium species. The distribution of U(VI) species is greatly influenced by pH. Due to the complexity and diversity of natural water environments, the photocatalysts used for U extraction must have a relatively wide selectivity for different U(VI) species to improve uranium extraction efficiency. Herein, the studies on photocatalytic uranium extraction in recent years are listed in Table 1 [7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31][32][33][34][35][36][37][38][39][40][41][42][43][44][35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72].

Table 1.

The photocatalytic U(VI) reduction performance over different catalysts.

| Photocatalysts | C | U(VI) | a | pH | Light | RR (%) | b | t (min) | c | Ref. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TiO | 2 | /Fe | 3 | O | 4 | 0.1 mM | 4.0 | UV light (100 W high-pressure mercury lamp) | 100, 30 | [7] | [35] | |||

| GO/KTO | 0.21 mM | 6.0–8.0 | UV-visible light (500 W Xe lamp) | 100, 60 | [8] | [36] | ||||||||

| TiO | 2 | 0.2 mM | 5.0 | UV light (350 W mercury discharge lamp) | 100, 100 | [9] | [37] | |||||||

| C | 3 | N | 5 | /RGO | 10 mg L | −1 | 5.0 | 300 W Xe lamp (λ ≥ 425 nm, 3.08 mW/cm | 2 | ) | 94.9, 100 | [10] | [38] | |

| ZnO/rectorite | 5 mg L | −1 | --- | 300 W Xe arc lamp | 75, 150 | [11] | [39] | |||||||

| SrTiO | 3 | /TiO | 2 | electrospun nanofibers | 100 mg L | −1 | 4.0 | 400 nm with monochromatic light | - | [12] | [40] | |||

| SiO | 2 | /C nanocomposite | 100 mg L | −1 | 5.0 | UV–vis absorption spectra | 94.2, 120 | [13] | [41] | |||||

| S-g-C | 3 | N | 4 | 0.12 mM | 7.0 | visible light (A 350 W Xe lamp with a 420 nm cutoff filter) | 95, 20 | [14] | [42] | |||||

| g-C | 3 | N | 4 | 27 mg L | −1 | 6.0 | 300 W Xe lamp (λ ≥ 420 nm) | 100, 20 | [2] | [31] | ||||

| C | 3 | N | 4 | 20 mg L | −1 | 4.0–8.0 | 300 W Xe lamp (λ ≥ 420 nm) | 92, 60 | [15] | [43] | ||||

| Nb/Ti NFs | 20 mg L | −1 | 5.0 | simulated solar light (450 W xenon lamp) | 90, 240 | [16] | [44] | |||||||

| CdS/TiO | 2 | 50 mg L | −1 | 6.0 | solar simulator with a 420 nm cut-off filter | 97, 240 | [17] | [45] | ||||||

| g-C | 3 | N | 4 | /GO | 80 mg L | −1 | 5.0 | 300-W Xe lamp | - | [18] | [46] | |||

| Fe | 3 | O | 4 | @PDA@TiO | 2 | 50 mg L | −1 | 8.2 | --- | 73, 300 | [19] | [47] | ||

| ZnFe | 2 | O | 4 | /g-C | 3 | N | 4 | 20 mg L | −1 | 5.0 | 8 W LED light | 94.62, 2400 | [20] | [48] |

| MoS | 2 | /g-C | 3 | N | 4 | 50 mg L | −1 | 4.5 | photocatalytic reaction box (CEL-HXF 300, Beijing Aulight Co. Ltd.) | 81.9, 120 | [21] | [49] | ||

| graphene-like S-C | 3 | N | 4 | 0.12 mM | 7.0 | sodium hydroxide aqueous solution. A 350 W Xe lamp (λ ≥ 420 nm) |

92, 30 | [22] | [50] | |||||

| Ti | 3 | C | 2 | /SrTiO | 3 | 0.21 mM | 4.0 | UV-visible light (wavelength, 320–2500 nm, 300 W Xe lamp) | 80, 180 | [23] | [51] | |||

| MoS | 2 | /THS | 50 mg L | −1 | 6.0 | 300 W Xe lamp equipped with an ultraviolet cutoff filter (λ ≥ 420 nm) | 98, 80 | [24] | [52] | |||||

| bentonite/Portland cement composite | 50 mg L | −1 | --- | --- | 96.97, 1140 | [25] | [53] | |||||||

| g-C | 3 | N | 4 | /TiO | 2 | 0.25 g·L | −1 | 6.9 | UV-visible light (wavelength, 320–780 nm, 300 W Xe lamp) | ∼80, 240 | [26] | [54] | ||

| CuO/CuFeO | 2 | 0.000126 mM | 8.2 | photoelectrochemical method: constant potential (−0.6 V vs. SCE) + simulated sunlight (150 W Xenon arc lamp with an AM1.5 G filter) | 100, 90 | [27] | [55] | |||||||

| TiO | 2 | /Fe | 3 | O | 4 | 13.5–108 mg L | −1 | 3.5–9.3 | 100 W high—pressure mercury lamp (λ = 365 nm) | 100, 30 | [7] | [35] | ||

| PCN-222 MOF | 500 mg L | −1 | 3–11 | 300 W Xe lamp (λ ≥ 420 nm) | 100, 5 | [45] | [27] | |||||||

| Ti | 3 | C | 2 | /CdS | 25–200 mg L | −1 | 4–10 | 300 W Xe lamp (λ ≥ 420 nm, 500 mW/cm | 2 | ) | 97, 40 | [28] | [56] | |

| ECUT-SO | 50 mg L | −1 | 4 | 300 W Xe lamp (λ ≥ 400 nm) | 97.8, 60 | [46] | [6] | |||||||

| Sn/In | 2 | S | 3 | 16,200 mg L | −1 | 3–9 | 500 W Xe lamp (λ ≥ 400 nm) | 95, 40 | [29] | [57] | ||||

| PCB/g-C | 3 | N | 4 | 100 mg L | −1 | 4 | 300 W Xe lamp (λ ≥ 400 nm) | --- | [30] | [58] | ||||

| TiO | 2 | 400 mg L | −1 | 5.5 | UV light (400 W mercury discharge lamp) | 95, 135 | [31] | [59] | ||||||

| B-g-C | 3 | N | 4 | 500 mg L | −1 | 7.0 | visible light (A 500 W Xe lamp with a 420 nm cutoff filter) | 93, 20 | [32] | [60] | ||||

| isotype g-C | 3 | N | 4 | 0.168 mM | 5.32 | --- | 98, 20 | [33] | [61] | |||||

| BiOBr@TpPa-1 | 30 mg L | −1 | 2.0–7.0 | 500 W Xe lamp (λ ≥ 420 nm) | 91, 540 | [34] | [62] | |||||||

| g-C | 3 | N | 4 | /LaFeO | 3 | 0.1 mM | 5.0 | 300 W Xe lamp (AM 1.5 G) | 94, 120 | [35] | [63] | |||

| BC-MoS | 2-x | 8 mg L | −1 | 5.0 | 300-W Xe lamp with AM 1.5 G | 92, 70 | [5] | [33] | ||||||

| ZIF-8/g-C | 3 | N | 4 | 10 mg L | −1 | --- | 300 W Xe lamp (λ ≥ 420 nm) | 100, 30 | [36] | [64] | ||||

| CdS/CN-33 | 0.1 mM | 6.0 | 500 W Xe lamp (λ ≥ 420 nm) | 100, 6 | [47] | [26] | ||||||||

| SnO | 2 | /CdCO | 3 | /CdS | 50 mg L | −1 | --- | 500 W Xe lamp (λ ≥ 420 nm) | 100, 70 | [37] | [65] | |||

| Te/SnS | 2 | 8 mg L | −1 | 4.8 | 300 W Xe lamp with AM 1.5 G filter | 98.6, 90 | [38] | [66] | ||||||

| Ag-doped SnS | 2 | @InVO | 4 | 60 mg L | −1 | 6.0 | 450 W Xe lamp (λ ≥ 400 nm) | 97.6, 100 | [39] | [67] | ||||

| MIL-53 (Fe) | 0.21 mM | 4.5 | visible light (285 W Xe lamp, λ ≥ 420 nm) | 80, 120 | [40] | [68] | ||||||||

| TiO | 2 | 0.21 mM | 2.7 | 15 W black-light fluorescent bulb (λ = 320∼400 nm) | 50, 780 | [41] | [69] | |||||||

| CdS | 0.95 | Te | 0.05 | -EDA nanobelt | 10–300 mg L | −1 | 3–9 | 300 W Xe lamp (λ ≥ 420 nm) | 97.4, 80 | [42] | [70] | |||

| graphene aerogel | 95.2 mg L | −1 | 5.0 | 350 W Xe lamp (λ = 420– 800 nm, 160 mW/cm | 2 | ) | 96, 200 | [43] | [71] | |||||

| TiO | 2 | 0.42 mM | 3.0 | 150 W Xenon arc lamp with an AM 1.5 G filter | 80, 240 | [44] | [72] |

Note: a U(VI) concentration. b RR is removal rate and c t is time.

The main purpose of photocatalytic uranium extraction is to convert soluble U(VI) into insoluble UO2 and (UO2)(O2)·4H2O [48][73] in order to recover them from solution. In general, photocatalytic U(VI) extraction includes the following process in the presence of catalyst. Light is irradiated on the catalyst to generate electron-hole pairs, which are used directly to reduce the soluble U(VI) to insoluble U species. Previous studies showed that uranium reduction may involve three different mechanisms of electron transfer [49][50][7,74].

The first proposed mechanism is a two-step single-electron transfer process, where U(VI) is first reduced to U(V) by accepting an electron (U(VI) + e− → U(V)) and then further reduced to U(IV) by accepting another electron (U(V) + e− → U(IV)) [51][52][53][54][75,76,77,78]. Furthermore, U(V) can undergo disproportionation under certain conditions to form both U(IV) and U(VI) (U(V) → U(IV) + U(VI)) [41][69].

The second mechanism involves a two-electron reduction process, where U(VI) accepts two electrons and is directly reduced to U(IV) (UO22+ + 2e− → UO2) [9][55][37,79].

The third mechanism involves the reaction of U(VI) with one electron and four protons to produce U(IV) and two water molecules in acidic solution (UO22+ + 4H+ + e− → U4+ + 2H2O), or the reaction of U(V) generated from the first mechanism with one electron and four protons to produce U(IV) and two water molecules (UO2+ + 4H+ + e− → U4+ + 2H2O). In addition, in some specific photocatalytic systems, excess electrons at the conduction band (CB) position will react with dissolved oxygen to generate ·O2− (O2 + e− → ·O2−), which can also reduce U(VI) via UO2+ + O2− → UO2 + 2O2 [44][72].

Obviously, the photocatalytic reduction of U(VI) involves various electron transfer processes. Suitable band structure and high carrier mobility are key factors in the design of photocatalysts. In general, when the redox potential of a target substance falls between the valence band maximum and the CB minimum of a catalyst, the substance may undergo a redox reaction. For the semiconductor itself, a CB potential higher than the U(VI) reduction potential (+0.41 V) is required to facilitate electron transfer [56][80]. Based on semiconductor photocatalysts, cadmium sulfide (CdS) received wide attention due to its narrow bandgap relative to visible light response and suitable CB position [57][81]. Qin et al. synthesized NiS@CdS interface Schottky heterojunction photocatalysts with different Ni/Cd molar ratios. The simulated removal efficiency of U(VI) in U-containing wastewater was as high as 99% under 90 min under solar light irradiation. This result is attributed to their good zeta potential and optical properties, narrow bandgap, and the high stability of the composite material [58][82].

The effective adsorption sites on the photocatalyst surface are very pivotal for photocatalytic uranium reduction, due to these sites determining the interaction between the catalyst and uranium species and the triggering of the reduction reaction [7][35]. Moreover, the final product of photocatalytic uranium extraction is mainly adsorbed on the surface of the catalyst, hence the type of product U species can be identified by various characterization methods, such as X-ray diffraction (XRD), X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), and X-ray absorption near edge structure (XANES) [59][29]. For instance, Chen et al. [60][83] use TT-POR COF-Ni as a photocatalyst to remove uranium. After photocatalytic reaction, the form of uranium was characterized by XPS, FT-IR, and PXRD. The high-resolution O 1s XPS indicated three different oxygen species, attributable to U-Operoxo, U = Oaxial, and H2O, respectively. While the high-resolution U 4f XPS showed a characteristic peak that corresponded to U 4f7/2 in UO2(O)2·2H2O at 381.9 eV, implying no change in the valence state of uranium. Moreover, the PXRD pattern also appeared at some new diffraction peaks at 2θ = 16.8°, 20.2°, 23.4°, and 25.1°, which can be attributed to metastudtite phase (UO2(O)2·2H2O, and the characteristic peak of UO2 at 2θ = 28.1° was not found. In addition, the appearance of peaks at 902 cm−1 assigned to the uranyl group and at 3460 cm−1 belonged to O-H vibration from H2O in the FTIR spectra after light irradiation further corroborated the formation of (UO2(O)2·2H2O.

Additionally, to identify the uranium-containing products of the photocatalytic experiments, U LIII-edge XANES spectroscopy, Fourier transform extended X-ray absorption fine structure spectroscopy (FT-EXAFS) and wavelet transform (WT) contour maps were measured [61][84].

2. Photocatalysts for Uranium Recovery from Solution

In the past decade, photocatalytic uranium extraction was regarded as a simple, efficient, and environmentally friendly method to solve U(VI) contamination in water. In general, TiO2 is the most widely used photocatalytic material in recent years for solving U(VI) pollution problems [9][44][62][63][64][65][66][67][24,37,72,85,86,87,88,89]. However, TiO2 as a photocatalyst indicated some potential disadvantages for the removal of U(VI): (1) recombination of photogenerated electron-hole pairs in TiO2 leads to the decline in photocatalytic efficiency [68][90]; (2) an artificial UV light source is required, and it is difficult to achieve U(VI) removal using sunlight, which demands high energy consumption [69][91]. With development of hybrid nanocomposite and heterojunction-structured catalysts, the separation efficiency of photogenerated carriers was remarkably improved and therefore promoted photocatalytic performance [8][26][55][36,54,79]. In addition, the surface structure of the photocatalyst itself including defects, vacancies, and heteroatom doping often influences catalytic activity.

2.1. Semiconductor Heterojunction Structure

A heterojunction represents the interface between two different semiconductors with unequal band structure, which can result in band alignments [70][92]. The energy level difference in semiconductor heterojunction drives the effective separation and migration of photogenerated charges, and therefore improves the photocatalytic ability for water pollution treatment and the degradation of organic pollutants [70][71][92,93]. In recent years, heterojunction materials were widely used in the photocatalytic extraction of U(VI) [72][73][94,95].

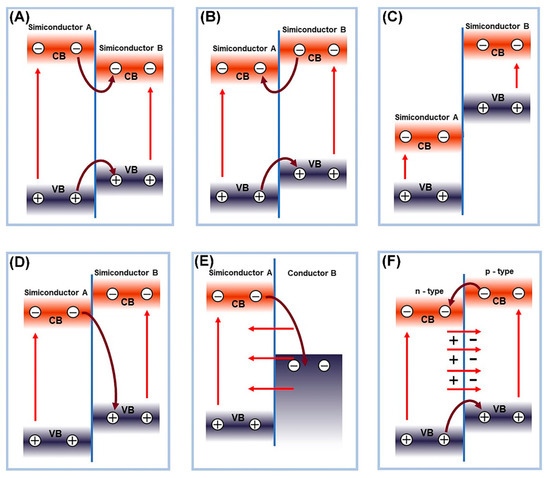

The schematic diagram of electron-hole separation in different types of heterojunctions is presented in Figure 1. According to the relative positions of the band structures of photocatalysts, binary heterojunction photocatalysts can be divided into three types, type I (straddling gap alignment, Figure 1A), type II (staggered gap alignment, Figure 1B), and type III (broken gap alignment, Figure 1C) [56][80]. Among them, the II-type heterojunction attracted extensive attention due to its unique band structure arrangement, ensuring effective separation of photogenerated charge carriers [74][75][96,97]. For example, g-C3N4/TiO2 binary heterojunction showed high U(VI) reduction ability compared with single g-C3N4 or TiO2 during photocatalytic extraction of uranium [26][54]. The g-C3N4/TiO2 with II-type heterojunction arrangement has a lower recombination rate of photogenerated electrons and holes and higher charge transfer efficiency, which was confirmed by the photoluminescence spectroscopy (PL), photocurrent response, and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy, revealing the origin of the enhancement of the photocatalytic activity. For a niobate/titanate (Nb/TiNFs) heterojunction prepared using a one-step hydrothermal method [16][44], electrons generated on titanate migrate to the CB of niobate due to their CB offset, which greatly suppresses the recombination of electron-hole pairs. The I-type heterojunction structure of the titanate and niobate composite materials compensates for the low photocatalytic activity of the monomer materials in U(VI) extraction. Moreover, composite materials, such as MoS2@TiO2 [24][52], MoS2@g-C3N4 [72][94], ZnS@g-C3N4 [76][98], CuS/TiO2, and so on, were used as excellent photocatalysts for U(VI) reduction.

Figure 1. Schematic diagram of electron-hole separation in different types of heterojunctions, (A) type-I heterojunction, (B) type-II heterojunction, (C) type-III heterojunction, (D) Z-scheme heterojunction, (E) Schottky heterojunction, and (F) p-n heterojunction.

The direct Z-scheme heterojunction and type II heterojunction have a similar energy band structure arrangement, but the direct Z-scheme heterojunction involves the recombination of electrons from the CB of semiconductor A and holes from the valence band of semiconductor B. This unique internal charge transfer mechanism allows the direct Z-scheme heterojunction to maintain both high oxidation and reduction abilities. Liu et al. [77][99] recently reported a ZnS/WO3 Z-type heterojunction photocatalyst with excellent visible light photocatalytic reduction performance for U(VI). When the two materials come into contact, electron transfer causes negative charge accumulation on the WO3 side and consumption of negative charge on the ZnS side, resulting in the formation of an internal electric field at the material interface. The internal electric field can serve as a one-way electron channel from WO3 to ZnS. Under illumination, the accumulated e− in the CB of WO3 migrates to the contact interface and recombines with the photo-induced h+ in the VB of ZnS, resulting in a long separation lifetime of e−. This greatly enhances the photocatalytic performance of the catalyst.

Note that when a metal/semiconductor forms a Schottky junction, the metal will accumulate a large number of electrons or holes. The resulting Schottky barrier will prevent electrons and holes from transferring to the semiconductor, ensuring single one-way transfer of electrons and holes, promoting the separation of photo-generated electrons and holes, and correspondingly improving the photocatalytic performance. Qin et al. [58][82] synthesized a NiS/CdS composite photocatalyst and demonstrated the existence of an interface Schottky junction between CdS and NiS, boosting spatial charge separation through density functional theory (DFT) calculations for highly efficient photocatalytic reduction in U(VI). The resultant U(VI) extraction efficiency reached 99% within 90 min from the uranium-containing solution. Dai et al. [78][100] first synthesized a magnetic graphene oxide-modified graphitic carbon nitride (mGO/g-C3N4) nanocomposite material, which can effectively catalyze the reduction in U(VI) from wastewater under visible light irradiation from LEDs, achieving a U(VI) extraction efficiency as high as 96.02%. Wan et al. [79][101] used S-injected engineering to functionalize the atoms into the TiO2/N-doped hollow carbon sphere (TiO2/NHCS) heterostructure to form Schottky junctions for spatially separating photogenerated electrons and optimizing the TiO2 energy level structure. The results show that the reduction efficiency of U(VI) within 20 min exceeded 90% and the removal rate per unit mass reached 448 mg g−1.

2.2. Defective Semiconductors

In photocatalysis, defect is a vital parameter to be pre-considered for the design of photocatalysts and catalytic performance. Crystallographic defects, which often occur at where the perfect periodic arrangement of atoms or molecules in the crystalline materials is disrupted or broken, inevitably lead to the imperfection of perfect crystal structure and therefore widely exist in all photocatalytic materials and increase active sites and greatly promote photocatalytic performance [80][102]. For semiconductors, the band structure can be improved by adjusting the defects, and thereby improving their light absorption capacity [59][29]. In addition, surface defect centers can also act as reactive sites, increasing the effectively active surface area. As one of the most common defects in semiconductor materials, vacancies can improve the photocatalytic performance by adjusting the electronic structure and light absorption capability [81][82][103,104]; for example, oxygen vacancy-rich tungsten oxide nanowires (WO3-x) have a narrower bandgap energy and higher charge carrier separation efficiency compared to regular WO3 [83][105]. DFT calculations further demonstrated that the introduction of oxygen vacancies (OVs) in WO3-x resulted in the spin-polarized state of W 3d electrons in WO3-x, greatly suppressing the recombination of photogenerated electrons and holes. Compared to WO3, WO3-x exhibited higher photocatalytic performance in U(IV) reduction. Hydrothermal reaction of a carbonized bacterial cellulose (BC) with thiourea and sodium molybdate dihydrate afforded a heterojunction-structured BC-MoS2, followed by H2/Ar mixed plasma treatment to generate S-vacancies (SVs) in MoS2 and form BC-MoS2-x heterojunction containing Schottky junction and SVs, which were used as photocatalysts for efficient uranium reduction. The resultant removal rate of uranium over a wide range of U(VI) concentrations was up to 91% [5][33]. Li et al. constructed an oxygen vacancy (OVs)-rich g-C3N4-CeO2-x heterojunction [84][106], kinetic characterization, and DFT calculations show that photogenerated electrons were transferred from g-C3N4 to a CeO2-x heterojunction through the built-in electric field generated by the heterojunction and were captured by shallow traps created by surface vacancies, and thereby achieving spatial separation. The separation rate and lifetime of photoinduced carriers were significantly increased, and photocatalytic activity for U(VI) reduction was significantly enhanced (39 times higher than that of g-C3N4).

2.3. Elemental Doping of Semiconductors

Doping can modify the surface structure, light absorption, defects, charge density, and carrier separation efficiency of photocatalytic materials [85][107]. In recent years, element-doped materials received extensive attention in the field of photocatalytic U(VI) reduction. Wang et al. [86][108] used non-metallic-doped photocatalysts and carbon-doped boron nitride (BN) BCN nanosheets for photocatalytic uranium reduction. By optimizing composite, calculations of energy gap and density of state of BCN, and experimental date, the results show that the doping in the form of carbon rings could regulate the bandgap and electronic structure by manipulating carbon amount. The introduction of carbon rings improved the surface structure and light absorption capacity of the catalyst, and the extraction rate of U(VI) reached 97.4% under visible light irradiation for 1.5 h. For the Ag-doped CdSe (Ag-CdSe) nanosheet, the doping of Ag resulted in an increase in the density of photogenerated carriers and a narrowed bandgap, while also suppressing the recombination of photogenerated electrons and holes [87][109]; 3% Ag-CdSe nanosheets reached a removal rate of U(VI) of 96%, which is 1.9 times higher than that of the original CdSe nanosheets (50%). To achieve higher photocatalytic efficiency in the extraction of U(VI), up-conversion Er-doped ZnO nanosheets were used as a photocatalyst [88][110]. Er doping induced up-conversion properties and suppressed recombination of photogenerated carriers, therefore enhancing light absorption capacity and accelerating U(VI) extraction. At an initial U(VI) concentration of 200 mg L−1, 4% Er-doped ZnO reached a high extraction efficiency of uranium at about 91.8% within 3 min.

2.4. Other Strategies

The band structure, light absorption, and carrier separation efficiency of photocatalysts are some key factors in affecting the photocatalytic performance. However, since the photocatalytic extraction of U(VI) occurs on the surface of the catalyst, optimizing the surface structure of the catalyst is another important method for improving photocatalytic performance. To further enhance the U(VI) extraction ability of carbon nitride photocatalysts, a one-step molten salt method was adopted to prepare a new bifunctional carbon nitride material (CN550) [89][111]. Compared with g-C3N4, CN550 has a high surface area, good adsorption capacity, and a high photocatalytic activity. More recently, various porous framework materials, such as metal–organic frameworks (MOFs), covalent organic frameworks (COFs), and hydrogen-bonded organic frameworks (HOFs), were regarded as the state-of-the-art materials for photocatalytic uranium extraction due to their high surface area and more active sites. Li et al. [45][27] proposed a new uranium extraction strategy based on post-synthetically functionalized MOF PCN-222, which is an extremely robust MOF, composed of Zr6(μ3-O)4(μ3-OH)4(H2O)4(OH)4 clusters and photoactive meso-tetra(4-carboxyphenyl)porphyrin (TCPP) linkers. PCN-222 was treated with aminomethylphosphonic acid and ethanephosphonic acid to afford PN-PCN-222 and P-PCN-222, respectively. The uranium uptake results show that PN-PCN-222 can completely remove uranyl ions in an extremely wide uranyl concentration range in solution and reach a very high absorption capacity at about 1289 mg g−1, breaking the maximum adsorption capacity of previously reported MOF materials. Under visible light irradiation, the photo-induced electrons in the PN-PCN-222 matrix reduce the U(VI) pre-enriched in PN-PCN-222, producing neutral uranium species that disperse the MOF structure, exposing more active sites to capture more U(VI). Overall, the development of photocatalytic strategies for efficient U(VI) extraction is recognized as an efficient, environmentally friendly, and cost-effective approach, while rational design and optimization of photocatalysts made significant progress in photocatalytic technology. At present, many articles describe the design of photocatalysts and the principles of photocatalytic systems in detail, and researchers can obtain more inspiration from them [59][90][91][29,112,113].