Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Lara Baticic and Version 2 by Dean Liu.

Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) is an aggressive malignancy characterized by rapid proliferation, early dissemination, acquired therapy resistance, and poor prognosis. Early diagnosis of SCLC is crucial since most patients present with advanced/metastatic disease, limiting the potential for curative treatment. While SCLC exhibits initial responsiveness to chemotherapy and radiotherapy, treatment resistance commonly emerges, leading to a five-year overall survival rate of up to 10%. New effective biomarkers, early detection, and advancements in therapeutic strategies are crucial for improving survival rates and reducing the impact of this devastating disease.

- small cell lung carcinoma (SCLC)

- biomarkers

- diagnosis

- therapeutic targets

1. Introduction

Lung cancer remains a significant global health concern, with staggering mortality rates. According to GLOBOCAN, it accounted for 2.1 million new cases and 1.8 million deaths in 2018, making it the leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide [1]. Lung cancer is categorized into two main histological types: non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and small cell lung cancer (SCLC). NSCLC comprises approximately 85% of cases, while SCLC represents around 15% [2]. SCLC is an aggressive neoplasm characterized by rapid proliferation, early dissemination, metastases, acquired therapy resistance, and poor outcomes [3]. Each year, approximately 250,000 new cases of SCLC are reported, resulting in at least 200,000 deaths worldwide [1]. While historically more common in men, the prevalence of SCLC among women has risen due to global smoking trends. Exposure to tobacco carcinogens (polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and tobacco-specific nitrosamines) is considered a key risk factor for SCLC, as only 2% of all SCLC cases are among never-smokers [4]. Early diagnosis of SCLC is crucial as most patients present with metastatic disease, limiting the potential for curative treatment. While SCLC exhibits initial responsiveness to chemotherapy and radiotherapy, treatment resistance often emerges, leading to a five-year overall survival rate of only 10% [5]. Poor prognosis is associated with factors such as male gender, poor performance status, and age over 70 [5][6][5,6]. Diagnostic procedures for SCLC typically involve physical examination, performance status evaluation, laboratory tests, and imaging techniques, including contrast-enhanced CT scans of the chest and abdomen, brain MRI or CT, and optional FDG PET/CT for limited-stage disease. Pathological examination following bronchoscopy, lymph node biopsy, and metastatic lesion biopsy is essential for accurately classifying SCLC [5]. To combat the high mortality rates associated with lung cancer, smoking cessation, and prevention remain the most critical interventions in reducing lung cancer mortality [5][6][5,6].

Common clinical manifestations of SCLC at diagnosis include central tumor masses, mediastinal involvement, and extrathoracic spread in 75–80% of patients [6]. Symptoms may include cough, wheezing, dyspnea, hemoptysis, weight loss, pain, fatigue, and paraneoplastic syndromes. Metastasis frequently occurs in the brain, liver, adrenal glands, bone, and bone marrow, often resulting in neurological deficits and paraneoplastic syndromes [7].

With the addition of programmed cell death protein-1 (PD-1) and programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) inhibitors to chemotherapy in the first line of extensive small cell lung cancer (SCLC), a step forward has been made in improving overall treatment outcomes for patients with SCLC [8]. In routine clinical practice, there are currently no available predictive biomarkers for immunotherapy response, and the use of programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) and tumor mutational burden (TMB) testing is not recommended [5]. The need for biomarkers to predict treatment response in patients with SCLC is urgent. Potential biomarkers such as PD-L1 expression, high TMB (TMB-H), and microsatellite instability (MSI-H) need further investigation for applicability in SCLC. Effective biomarkers, early detection, and advancements in therapeutic strategies are crucial for improving survival rates and reducing the impact of this devastating disease.

2. Pathology of SCLC

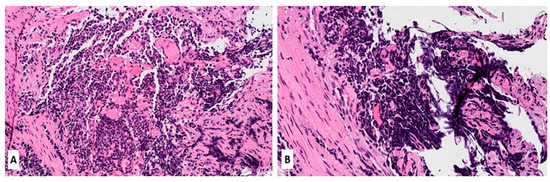

SCLC belongs to the spectrum of neuroendocrine pulmonary neoplasms that share some common morphologic, ultrastructural, immunohistochemical, and molecular genomic characteristics [9][10][9,10]. Four major neuroendocrine pulmonary neoplasms are carcinoids (typical and atypical) and neuroendocrine carcinomas (SCLC and large cell neuroendocrine carcinomas; LCNEC). A typical carcinoid is a low-grade neoplasm, and atypical carcinoid is intermediate-grade, whereas both neuroendocrine carcinomas are, per definition, high-grade neoplasms. The current evidence suggests that carcinoids (typical and atypical) are closely related and etiologically different from SCLC and LCNEC [9][10][9,10]. Carcinoids are not precursor lesions of neuroendocrine carcinomas (SCLC and LCNEC) and may be seen more frequently among non-smokers [9][10][9,10]. A small subset of carcinoids can be seen in patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia 1 (MEN1) syndrome (OMIM#131100), while somatic MEN1 gene mutations are commonly observed in carcinoids [9][10][9,10]. Rare cases of histologic transformation of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)—or anaplastic large kinase (ALK)-altered pulmonary adenocarcinomas have also been well-documented [11]. It is widely accepted that SCLC has the same endodermal origins as other major subtypes of lung carcinoma (e.g., adenocarcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma), arising from multipotent precursor cells [9][10][12][13][9,10,12,13]. Morphologically, SCLC is composed of densely packed, small neoplastic cells with scanty cytoplasm and finely granular nuclear chromatin but without prominent nucleoli; nuclear molding and smudging are commonly present (Figure 1A,B). The cells are round or oval, although spindle cells (fusiform pattern of cancer cells) are frequently seen. Mitotic figures are numerous, while the tumor necrosis and crush artifacts may be extensive.

Figure 1. (A,B) Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) stain of a lung biopsy showing a small cell carcinoma with sheet-like diffuse growth pattern and basophilic appearance (A, magnification 10×); Image 1B reveals a prominent nuclear molding of neoplastic cells (magnification 20×).

3. Genomic Features of SCLC

Recent research has focused on understanding the genetic basis of SCLC to identify new therapeutic targets and develop more effective treatments [20]. Genetic alterations contribute significantly to the development and progression of SCLC. Concomitant inactivation of two tumor suppressor genes, TP53 and RB1, is found in most SCLC cases [21][22][21,22] and is found in up to 90% and 50–90% of SCLC cases, respectively. These molecular features are strikingly different from those seen in NSCLC, in which various oncogenic driver mutations/fusions prevail (e.g., EGFR, KRAS, ALK, BRAF, RET, ROS1, MET, NTRK1-3, HER2/ERBB2) [22][23][22,23]. Additionally, genetic alterations contributing to SCLC’s development include amplifying the MYC family of oncogenes (MYC, MYCL, and MYCN), inactivation of the phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) tumor suppressor gene, and mutations in the Notch signaling pathway. Genomic alterations of MYC family members are seen in SCLC and represent biomarkers of poor prognosis. In particular, MYCN alterations are related to SCLC cases with immunotherapy failure. The most important genes altered in SCLC in humans are summarized in Table 1. Different studies have identified recurrent mutations in chromatin remodeling genes, such as ARID1A, ARID1B, and SMARCA4, which regulate gene expression. These mutations may contribute to the dysregulation of critical genes involved in cell proliferation and survival, leading to the development of SCLC, characterized by a high frequency of mutations in genes that regulate cell cycle and DNA damage response pathways, such as TP53, RB1, and PTEN. Additionally, SCLC often exhibits widespread chromosomal instability, with frequent amplifications and deletions of large genome regions. In addition to these genetic alterations, SCLC is characterized by a high frequency of copy number alterations, including amplification of MYC family members and deletion of the tumor suppressor gene cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (CDKN2A) [24]. In addition, the changes in the stroma and immune microenvironment are additional factors involved in the pathogenesis of SCLC [25]. Overall, the genetic landscape of SCLC is complex and heterogeneous, with multiple genetic alterations contributing to its aggressive phenotype. Understanding the underlying genetic mechanisms of SCLC is crucial for developing effective targeted therapies and personalized treatment strategies for patients with this aggressive cancer. SCLC mutational characteristics reveal a clear causal connection with smoking. Direct scientific evidence confirms that carcinogens from tobacco are responsible for initiating SCLC [26]. Genomic profiling in patients with SCLC has not revealed mutationally defined subtypes of SCLC. However, due to the lack of larger studies, this may be a consequence of the insufficient number of tumor samples included in analyses. Therefore, there is a substantial need for clinical trials that include the analyses of tumor tissue to identify vital genomic triggers. However, there is an accentuated difficulty in tumor material collection. Ethnicity or smoking status did not affect the consistency of mutational differences; however, the prevalence of oncogenic triggers is considered higher in never-smokers with SCLC compared to tobacco users [27]. In addition, genetically modified mice have provided critical genetic lessons and contributed to the knowledge of molecular mechanisms of SCLC etiopathogenesis, metastasis, and response to treatment. It has been shown that tumors in mice show genetic alterations and histological features like those in humans. Ferone et al. provided a comprehensive review of lung cancers and lessons from mouse studies, showing an enormous contribution of animal studies in pulmooncology [28].Table 1. Most important genes altered in SCLC (mostly according to memorial Sloan Kettering-integrated mutation profiling of actionable cancer targets—MSK-IMPACT sequencing of SCLC tumors)—data adopted from Cheng et al. [29], Rudin et al. [23], and Liu et al. [30].

| Gene | Aliases | Gene Location on Human Chromosome and Number of Amino Acids | Gene Alteration in SCLC | Known Function and Features | Frequency of Mutation in SCLC (% in Various Cohorts) | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TP53 | Tumor protein 53; p53; Phosphoprotein P53; Antigen NY-CO-13; Transformation-Related Protein 53; BCC7, LFS1, TRP53, tumor protein BMFS5 |

Chromosome 17 at position 17p13.1.; 375 amino acids |

Inactivating mutation; deletion | Nuclear phosphoprotein involved in the regulation of cell proliferation; tumor suppressor; transcription regulation | 77–89 | Chang et al. [31] Rudin et al. [23] |

| RB1 | RB1, pRb, RB, retinoblastoma 1, OSRC, PPP1R130, p105-Rb, pp110, Retinoblastoma protein, RB transcriptional corepressor 1, p110-RB1 | Chromosome 13 at position 13q14.1-q14.2.; 928 amino acids |

Inactivating mutation; deletion; loss or inactivation of both copies of the gene | Tumor suppressor protein that is dysfunctional in several major cancers. Prevents excessive cell growth by inhibiting cell cycle progression -key regulator of the G1/S transition of the cell cycle | 50–90 | George et al. [21] Febres-Aldana et al. [32] |

| KMT2D | KMT2D, ALR, KABUK1, MLL2, MLL4, lysine methyltransferase 2D, histone-lysine methyltransferase 2D, TNRC21, AAD10, KMS, CAGL114 | Chromosome 12 at position 12q13.12.; 5316 amino acids |

Inactivating mutation; deletion; gene fusion; truncating nonsense/frameshift/splice site mutations | Key regulator of transcriptional enhancer function; major enhancer regulator in mammalian cells, including regulation of development, differentiation, metabolism, and tumor suppression. | 5–13 | Wu et al. [33] Simbolo et al. [34] Augert et al. [35] |

| CREBBP | AW558298, CBP, CBP/p300, KAT3A, p300/CBP, RSTS, CREB binding protein, RSTS1, MKHK1 | Chromosome 16 at position 16p13.3. 2414 amino acids. |

Inactivating mutation, deletion | Crucial role in transcriptional regulation and chromatin remodeling. Interacts with various transcription factors and coactivators, influencing the expression of target genes involved in cell growth, differentiation, and development. | 4–10 | Carazo et al. [36] Jia et al. [37] |

| PTEN | PTEN, 10q23del, BZS, CWS1, DEC, GLM2, MHAM |

Table 2. Potential biomarkers in small cell lung carcinoma.

| Biomarker | Type | Potential Application | References | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Delta-like ligand 3 DLL3 |

Tumor-specific marker | Biomarker for SCLC prognosis | Chen et al. [58] | ||||||||||

| Circulating tumor cells (CTC) | Liquid biopsy biomarker | Prognostic biomarker for therapy evaluation of therapy efficacy | Roumeliotou et al. [59 | ||||||||||

| Biomarker for treatment efficacy and relapse detection | Almodovar et al. | [ | 60] | ||||||||||

| Exosomes | Extracellular vesicles | Non-invasive biomarkers for prognosis | Zhang et al. [61] | ||||||||||

| , | MMAC1, PTEN1, TEP1, phosphatase and tensin homolog, Phosphatase and tensin homolog, PTENbeta | Chromosome 10 at position 10q23.3. 403 amino acids |

inactivating mutations, deletions, or loss of expression | Tumor suppressor involved in the regulation of the | |||||||||

| MYC proto-oncogene/bHLH transcription factor (MYC) | PI3K/AKT/mTOR | pathway, which plays a critical role in cell survival and proliferation. PTEN’s protein phosphatase activity may be involved in the regulation of the Cell cycle, preventing cells from growing and dividing too rapidly. | 3–10 | Sivakumar et al. | Genetic alteration | [ | Potential biomarker for targeted therapy | Taniguchi et al. [62]38] Zhang et al. [39] |

|||||

| FAT1 | CDHF7, CDHR8, FAT, ME5, hFat1, FAT atypical cadherin 1 | Chromosome 4 at position 4q35.2. 4410 amino acids |

Inactivation mutation; deletion | [ | 41 | ] | |||||||

| Programmed death-ligand 1 | Cell-cell adhesion, migration and communication, regulation of tissue growth, cell polarity, and migration; tumor suppressor gene | (PD-L1) | 2–10 | JiaXin et al. | [ | 40] Pop-Bica et al. |

Immune checkpoint protein[41] | ||||||

| Potential biomarker for immunotherapy response | Taniguchi et al. | [ | 62] | PIK3CA | PIK3CA, CLOVE, CWS5, MCAP, MCM, MCMTC, PI3K, p110-alpha, PI3K-alpha, phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha, CLAPO, CCM4 | Chromosome 3 at position 3q26.3.; 1068 amino acids |

Activating mutation; mutations in specific regions | The PIK3CA gene for synthesis of the catalytic subunit alpha of the enzyme phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, having crucial role in cell growth, proliferation, and survival |

1–7 | ||||

| Tumor mutational burden (TMB) | Mutation load of a tumor | Potential biomarker for immunotherapy response | Taniguchi et al. [62] and Li et al. [65] | Hung et al. | [ | 42] Pop-Bica et al. NOTCH1 |

NOTCH1, Notch1, 9930111A19Rik, Mis6, N1, Tan1, lin-12, AOS5, AOVD1, hN1 | Chromosome 9 at position 9q34.3. 2527 amino acids |

Inactivating mutation | Tumor suppressor; involved in cell signalling processes | 1–6 | Li et al. [43] Roper et al. [44] Herbreteau et al. [45] |

|

| NF1 | NFNS, VRNF, WSS, neurofibromin 1 | Chromosome 17 at position 17q11.2. 2818 amino acids |

Inactivating mutation, deletion | Tumor suppressor. Neurofibromin 1 plays a role in regulating cell growth and proliferation by negatively regulating the activity of Ras, associated with uncontrolled cell growth. | 3–4 | Ross et al. [46] Shimizu et al. [47] |

|||||||

| APC | BTPS2, DP2, DP2.5, DP3, GS, PPP1R46, adenomatous polyposis coli, WNT signaling pathway regulator | Chromosome 5 at position 5q22.2. 2843 amino acids |

Inactivating mutation, deletion | Crucial role in regulating the Wnt signaling pathway and controlling cell proliferation, growth, differentiation, and migration. | 3–4 | Jin et al. [48] Grote et al. [49] |

|||||||

| EGFR | ERBB, ERBB1, HER1, NISBD2, PIG61, mENA, epidermal growth factor receptor, erbB-1, ERRP | Chromosome 7 at position 7p12.1. 1210 amino acids |

Activating mutation | Oncogene; a receptor tyrosine kinase that plays a critical role in cell growth, proliferation, and survival; involved in RAS signaling pathway. | 3–4 | ] | |||||||

| ] | Ding et al. | [ | 50 | ] | Hao et al. [51] | ||||||||

| KRAS | C-K-RAS, CFC2, K-RAS2A, K-RAS2B, K-RAS4A, K-RAS4B, KI-RAS, KRAS1, KRAS2, NS, NS3, RALD, RASK2, K-ras, KRAS proto-oncogene, GTPase, c-Ki-ras2, OES, c-Ki-ras, K-Ras 2, K-Ras, Kirsten Rat Sarcoma virus | Chromosome 12 at position 12p12.1. 189 amino acids |

Activating mutation | A GTPase involved in cell signalingpathways that regulate cell growth and proliferation (RAS/MAPK). KRAS mutations can lead to the constitutive activation of the KRAS protein, resulting in dysregulated cell signaling and increased cell proliferation. | 1–3 | Otegui et al. [52] Li et al. [53] |

|||||||

| NOTCH3 | CADASIL, CASIL, IMF2, LMNS, CADASIL1, notch 3, notch receptor 3 | Chromosome 19 at position 19p13.2. 2345 amino acids |

Inactivating mutation, deletion | Involved in cell signaling pathways. Notch signaling plays a critical role in cellular processes, such as cell fate determination, differentiation, and development. | <3 | Herbreteau et al. [45] Du et al. [54] |

|||||||

| ARID1A | B120, BAF250, BAF250a, BM029, C1orf4, ELD, MRD14, OSA1, P270, SMARCF1, hELD, hOSA1, CSS2, AT-rich interaction domain 1A | Chromosome 1 at position 1p36.11. 2254 amino acids |

Inactivating mutation, deletion | Tumor suppressor gene; plays a crucial role in regulating chromatin remodeling and gene expression; involved in various cellular processes, including DNA repair, cell cycle regulation, and differentiation. | <3 | Du et al. [54] Devarakonda et al. [55 |

PTPRD | HPTP, HPTPD, HPTPDELTA, PTPD, RPTPDELTA, protein tyrosine phosphatase, receptor type D, protein tyrosine phosphatase receptor type D, R-PTP-delta | Chromosome 9 at position 9p23.3. 1840 amino acids |

Inactivating mutation, deletion | Protein tyrosine phosphatase receptor that plays a role in regulating cell signaling pathways, including those involved in cell growth, differentiation, and migration. | <3 | Sato et al. [56] |

| ATRX | ATR2, JMS, MRXHF1, RAD54, RAD54L, SFM1, SHS, XH2, XNP, ZNF-HX, MRX52, alpha thalassemia/mental retardation syndrome X-linked, chromatin remodeler, ATRX chromatin remodeler | X chromosome at position Xq21.1. | Inactivating mutation, deletion | Tumor suppressor; plays a critical role in chromatin remodeling and the regulation of gene expression. ATRX is involved in maintaining the stability and structure of telomeres and in cell signaling | <2 | Du et al. [54] |

4. Biomarkers in SCLC

In contrast to NSCLC, the discovery of therapeutic targets in SCLC has not been easy, partly because driver mutations are in first-line loss of function or untargetable, e.g., MYC family members [23]. The recent division of SCLC into molecular subtypes based on the expression of transcription factors has provided an essential step in searching for new therapeutic targets for the disease. This classification system identifies four distinct subtypes of SCLC: achaete-scute homolog 1 (ASCL1), neurogenic differentiation factor 1 (NEUROD1), yes-associated protein 1 (YAP1), and POU class 2 homeobox 3 (POU2F3) [57]. New blood-based biomarkers for the early detection of lung cancer have been developed and evaluated, with several showing promising results. “Liquid biopsy”—biomarkers such as tumor-derived extracellular vesicles, circulating tumor cells (CTC), and circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) seem to be promising tools in cancer monitoring. For example, SCLC cells express different tumor-specific markers, including Delta-like protein 3 (DLL-3), which may be associated with a worse prognosis in patients with SCLC [58]. However, whether these biomarkers listed in Table 2 will impact cancer control in the population, especially in cancer with aggressive biologic behavior such as SCLC, remains unknown. To date, it seems that patients with SCLC have the greatest number of CTC, which was suggested to be a prognostic biomarker for clinically evaluating therapy efficacy [59]. Likewise, CTC-derived DNA and plasma cell-free DNA, along with their genomic alterations, have been recognized as potential non-invasive biomarkers that could provide insights into treatment efficacy and the occurrence of SCLC relapse [60]. Furthermore, the characterization of extracellular vesicles, such as exosomes, appears to be a promising tool and alternative source for various analytes in liquid biopsies [61]. This approach has the potential to significantly contribute to the identification of new biomarkers for the diagnosis and monitoring of SCLC patients, as well as the development of promising prognostic models. Emerging predictive and prognostic biomarkers are crucial and indispensable for selecting the most suitable therapeutic option for patients with SCLC.| Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) | |||

| Liquid biopsy biomarker | |||

| Microsatellite instability | |||

| (MSI-H) | Genetic marker of Microsatellite Instability | Potential biomarker for immunotherapy response | Taniguchi et al. [62] and Chang et al. [66] |

| Schlafen 11 (SLFN11) |

Liquid biopsy biomarker | Potential biomarker for the response on DNA damaging chemotherapy and PARP inhibition | Taniguchi et al. [62] and Zhang et al. [63] |