Acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) is a syndrome characterized by acute and severe decompensation of chronic liver disease (CLD) correlated with multiple organ failure, poor prognosis, and increased mortality. In 40–50% of ACLF cases, the trigger is not recognized; for many of these patients, bacterial translocation associated with systemic inflammation is thought to be the determining factor; in the other 50% of patients, sepsis, alcohol consumption, and reactivation of chronic viral hepatitis are the most frequently described trigger factors. Other conditions considered precipitating factors are less common, including acute alcoholic hepatitis, major surgery, TIPS insertion, or inadequate paracentesis without albumin substitution.

1. Introduction

Acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) represents a condition characterized by acute decompensation of underlying chronic liver disease (CLD) correlated with multiple organ failure, poor prognosis, and increased mortality.

The EASL (European Association for the Study of the Liver), NACSELD (North American Consortium for the Study of End-Stage Liver Disease), and APASL (Asia Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver) have proposed different definitions of ACLF syndrome; all are based on clinical features, associated with alterations of biological liver tests combined with organ failure

[1,2][1][2].

More than 13 distinct definitions of ACLF have been advanced so far, but the definitions from APASL and the European Association for the Study of Chronic Liver Failure (EASL-CLIF) Consortium are universally recognized

[3,4][3][4].

Thus, the consensus of the Asia-Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver (APASL) defined ACLF as acute liver injury manifested by jaundice (total bilirubin ≥ 5 mg/dL) and coagulopathy (INR ≥ 1.5), which evolves within four weeks with ascites with/without encephalopathy in a patient previously diagnosed with CLD.

According to the EASL-CLIF criteria, ACLF emerges in patients with previously compensated or decompensated liver cirrhosis who develop other organ failures. The EASL-CLIF criteria exclude patients previously diagnosed with HCC (hepatocellular carcinoma), HIV (Human Immunodeficiency Virus), or severe comorbidities

[5]. The EASL-CLIF criteria, compared to the NACLSELD and APASL criteria, define a relatively enlarged spectrum of disease severities, including ACLF disease phases with better prognosis (phases 1/2) and outcomes, as well as advanced phases with multiple organ failure, high short-term mortality, and poor prognosis

[4,6][4][6].

The NACSELD criteria were defined initially for patients hospitalized with decompensated cirrhosis and bacterial infections, excluding previous malignancies, HIV, or previous organ transplantation

[5]. These criteria completed the EASL-CLIF criteria; therefore, ACLF was defined by the presence of at least two extrahepatic organ failures, including shock, the need for vasopressors despite adequate intravenous fluid therapy, encephalopathy stage 3/4, renal replacement, and/or mechanical ventilation

[1]. The NACSELD definition does not differentiate between distinct disease phases and stages of ACLF, so it may underdiagnose ACLF.

The APASL criteria used a wide disease spectrum focusing on liver failure as central to the ACLF definition

[2]. The APASL and ACLF definitions were derived from acute liver failure, which develops in patients with preexisting chronic liver disease or liver cirrhosis, but these definitions exclude patients with decompensated cirrhosis or a history of infection

[3,5][3][5]. Therefore, patients with acute hepatic injury, such as reactivation of viral hepatitis, drug-induced liver injury, or surgical procedures, and those with cirrhosis without any previous infections or variceal hemorrhage meet the APASL ACLF criteria if these factors can lead to jaundice and coagulopathy and are followed by ascites or hepatic encephalopathy within four weeks. Although the APASL definition presumes the existence of underlying chronic liver disease, unlike the EASL-CLIF criteria, it does not distinguish between ACLF with or without cirrhosis

[5,7][5][7].

Despite the worldwide diversity of ACLF definitions related to diagnosis, precipitating factors, underlying comorbidities, organ failure, and management, patients with ACLF have an invariably poor prognosis. The most recently and exhaustive guideline for the current data in ACLF was elaborated in 2022 by Bajaj et al., and it represents the official practice recommendation of the American College of Gastroenterology, being structured on statements considered useful and clinically relevant. The guideline provides a list of recommendations regarding definitions, diagnosis, key pathogenetic mechanisms, precipitating factors, and a complex therapeutic approach

[5].

2. Etiological Factors of ACLF

In 40–50% of ACLF cases, the trigger has not been recognized. For many of these patients, bacterial translocation and systemic inflammation are thought to be the determining factors

[8]; in the other 50% of patients, sepsis, alcohol consumption, and reactivation of chronic viral hepatitis (B, C, E)

[2] are the most described precipitating factors. Other precipitating conditions are less common (approximately 8%), including acute alcoholic hepatitis, surgery, or TIPS insertion. Paracentesis without albumin substitution has also been described

[4,9][4][9]. The main acute precipitating factors in ACLF, according to Gawande et al., are listed in

Table 1 [10].

Evidence on ACLF caused by acute hepatic insults of a viral etiology is still being researched, further studies being essential for a concluding evaluation of etiology, outcome, organ failure, and mortality predictors. Hepatitis viruses are some of the main etiological factors for acute hepatic insults resulting in ACLF. Hepatotropic viral infections include hepatitis B virus reactivation, (HBV) superinfection with hepatitis A virus (HAV), hepatitis E virus (HEV), or more rarely, reactivation of HCV infection.

HBV reactivation has been recognized as a common factor involved in ACLF development

[11,12,13][11][12][13]. Studies have suggested that 15–37% of patients with HBV infection develop acute exacerbations within four years

[14], as well as episodes of ACLF; the mortality rate for these patients is between 30% and 70%

[4,15][4][15]. In the Asia-Pacific region, hepatitis B appears to be the most common cause of ACLF. In China, 80% of ACLF cases are due to hepatitis B, and reactivation of HBV as an acute hepatic insult is found in more than 50% of cases

[16].

HAV infection can occasionally cause liver failure in patients with or without preexisting chronic liver disease. Over time, a series of studies highlighted HAV as an acute insult in ACLF and provided evidence of increased short-term mortality

[2,17][2][17].

Agrawal et al. reported the presence of ACLF and HAV as an acute insult that occurred in patients with underlying liver cirrhosis secondary to NAFLD (non-alcoholic fatty liver disease)

[18]. Kahraman et al. also reported a human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive case in a patient who developed ACLF due to an acute HAV infection with liver cirrhosis due to NAFLD

[19]. Duseja et al. emphasized that HAV infection in patients with the pre-existing chronic liver disease could be responsible for worsening ACLF

[20].

Other authors have investigated the role of HAV infection in patients with chronic hepatitis or liver cirrhosis secondary to HBV infection, suggesting that the association of HAV superinfection with HBV patients occasionally leads to ACLF, in HBV patients both with and without liver cirrhosis

[21,22,23][21][22][23]. Some studies have associated HAV infection in HCV infection with increased mortality

[24[24][25],

25], although there have been several contrary opinions suggesting that HAV superinfection is associated with decreased HCV replication, which could lead to HCV clearance.

[26,27,28][26][27][28].

Therefore, it is currently suggested that HAV infection, as an acute insult, precipitates the development of ACLF in patients with any chronic liver disease, especially liver cirrhosis, an important role being apparently attributed to host genetic factors determining different individual susceptibility

[29,30][29][30].

Many studies have reported HEV as one of the leading causes of ACLF in Asia and Africa, where HEV is endemic. The mortality rate of HEV-related ACLF is nearly 35%

[31]. HEV-related acute hepatitis in patients having underlying cirrhosis may complicate and worsen the primary disease and can result in ACLF. A majority of these patients may need early transplantation

[32,33,34][32][33][34].

The evidence that, generally, HCV infection rarely causes ACLF has been supported by numerous previous studies

[35[35][36][37][38][39][40],

36,37,38,39,40], but a reactivation of HCV infection is recognized to be one of the precipitating factors in ACLF induction

[9], considering the possibility that an acute HCV infection can result in acute fulminant liver failure

[3,41,42,43][3][41][42][43].

Bacterial products, such as muramyl-dipeptides, bacterial DNA, lipopolysaccharides, and peptidoglycans, are translocated from a permeable intestine into the blood continuously or discontinuously; therefore, they could initiate initial organ dysfunction

[44]. Bacterial translocation, the most important trigger of systemic inflammation, relies on the existence of ascites

[45].

Gastrointestinal bleeding is also a precipitating factor in triggering ACLF. Patients with ACLF have a significantly increased bleeding history compared to patients without ACLF

[46,47][46][47]. Rebleeding doubles the risk of ACLF, and these patients present a very high risk of death, so TIPS insertion could notably improve outcomes in critically decompensated cirrhotic patients

[47,48,49][47][48][49]; therefore, TIPS has been recommended by the recent international guidelines and Baveno

[50,51][50][51].

Host response is likely the main factor in determining ACLF severity and prognosis. The host immune reaction and the inflammatory cascade are of significance in this condition. The similarity between systemic inflammation determined by sepsis and ACLF motivates the idea that both conditions could have similar pathogenic mechanisms. Comparing patients with sepsis and patients with ACLF, Wasmuth et al.

[52] formulated the hypothesis of “sepsis-like immune paralysis” based on extremely reduced TNF-α pro-duction and decreased HLA-DR monocyte expression in patients with both sepsis and ACLF, with this cellular immune damage contributing to high mortality.

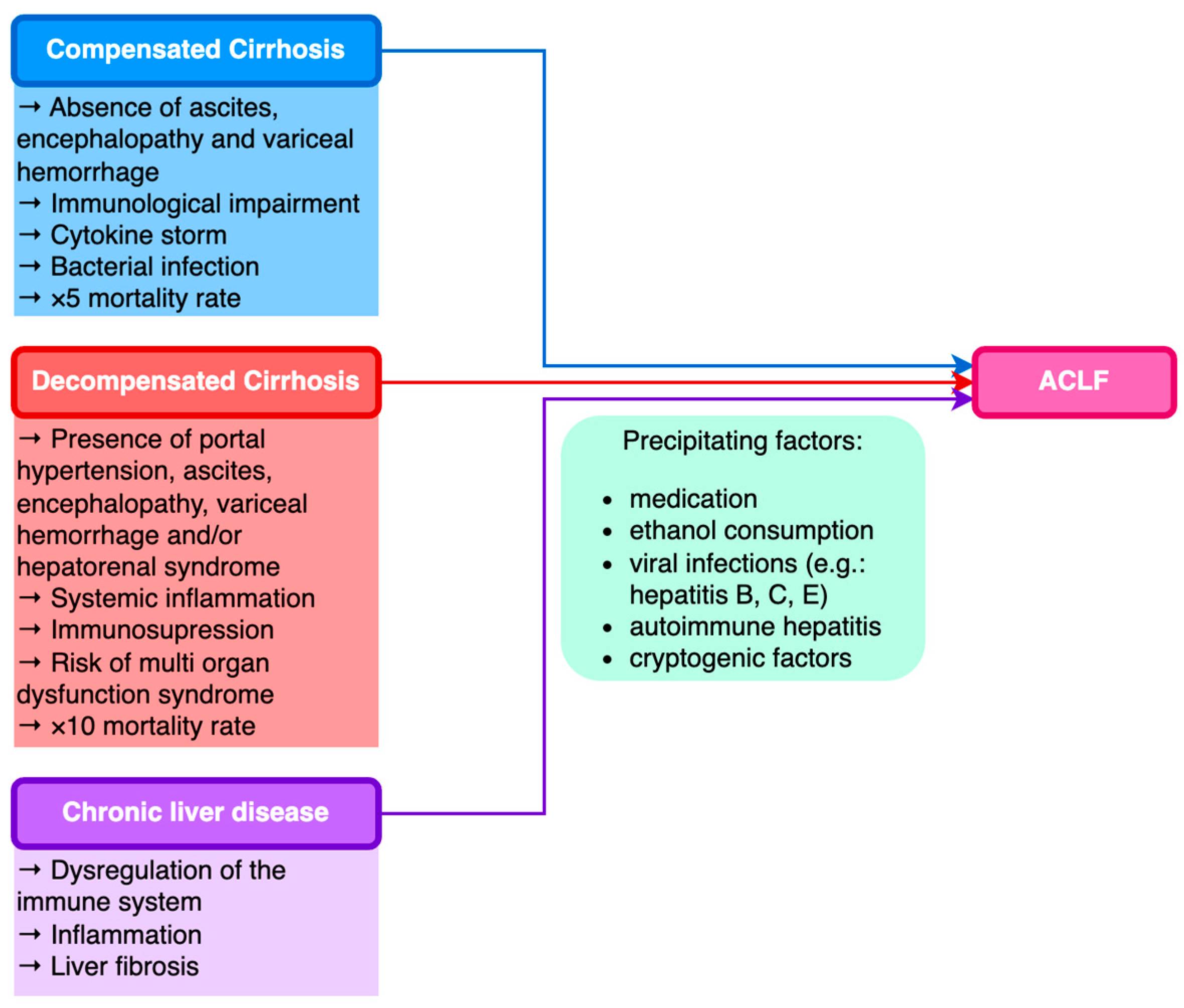

Current studies have identified that ACLF can occur in patients with both compensated and decompensated cirrhosis, as well as in patients with previous CLD without cirrhosis.

Table 2 presents the prevalence of ACLF in different CLD etiologies, according to data published in an exhaustive study conducted in 80,389 patients by Mahmud et al.

[53].

The World Gastroenterology Organization (WGO) formulated a classification of ACLF relying on the underlying liver disease: patients with underlying CLD and non-cirrhotic ACLF type A; patients with prior compensated cirrhosis and ACLF type B; and patients with prior decompensated cirrhosis and ACLF type C (

Figure 1)

[54,55][54][55].

Figure 1. Classification of ACLF based on underlying chronic liver disease.

Recent studies have revealed that ACLF represents 5% of all patients suffering from liver cirrhosis who are hospitalized, the average cost of hospitalization for these patients being three times higher than the cost for cirrhotic patients without complications and approximately five times higher than the cost for patients hospitalized for heart failure

[56].

The global mortality rate according to EASL-CLIF is 30% to 50%. Mortality rates in the United States, according to NACSELD in decompensated patients, were 27%, 49%, 64%, and 77%, the percentage increasing directly with the number of organs affected (1, 2, 3, or 4 organ failures, respectively)

[57,58][57][58].