2. Parkinson’s Disease

Parkinson’s disease is the second most prevalent neurodegenerative disorder worldwide after Alzheimer’s. It is estimated that there are 10 million people with PD globally

[7]. The disease has a higher prevalence in men than in women, typically occurring between the ages of 65 to 70. Although it can occur in individuals under 40, it represents only 5% of cases

[8]. The etiology is not entirely defined, but it could be multifactorial, resulting from interactions between genetic and environmental factors. Patients with an implicated gene are said to have familial or hereditary PD, while those with no known specific cause are said to have idiopathic Parkinson’s disease (IPD)

[7]. Approximately 10–15% of all patients diagnosed with PD have familial PD, which is characterized by mutations in one of the following genes:

SNCA, LRRK2, GBA, VPS35, PINK1, PARK7, and

PARK2 [7].

Regarding environmental factors, an association has been identified between PD and drug use, such as amphetamine, methamphetamine, or cocaine use, exposure to pesticides and heavy metals (such as iron, copper, manganese, lead, and mercury), exposure to solvents, or the entry of a virus

[7][9][7,9]. A meta-analysis of 104 studies showed a clear association between the risk of PD and exposure to solvents and pesticides, including the herbicide paraquat and the fungicide mancozeb

[10]. The results indicate that people exposed to these substances have twice the risk of developing this disease compared to those who are not.

The diagnosis of PD comprises a medical history and neurological evaluation in order to identify the presence of the four cardinal signs of the disease

[1]. Different tests, such as Dopamine Transporter Single-Photon Emission Computed Tomography (DAT-SPECT), F-fluorodopa PET, transcranial ultrasound, and genetic tests, can complement the neurological evaluation

[11]. In addition, the prescription of dopaminergic medications such as Levodopa and an evaluation of their response can be helpful

[7]. This is because other Parkinsonian syndromes, such as Progressive Supranuclear Palsy (PSP) and Multiple System Atrophy (MSA), do not respond to these dopaminergic drug therapies

[12].

In addition, NMSs, such as cognitive deficits, apathy, gastrointestinal dysfunction, cardiovascular problems, psychological disorders such as depression or anxiety, and sleeping problems, mainly RBD, can be considered for the diagnosis

[13][14][13,14]. PD patients may also have sensory deficits, including visual difficulties, altered pain processing, and OD

[13][15][16][17][13,15,16,17].

3. A Brief Review of the Evolution of Knowledge about Olfactory Dysfunction in Parkinson’s Disease

In 1975, Ansari and Johnson documented that 10 out of 22 patients with PD had OD

[18]. The study’s authors suggested that this condition might be related to an alteration in the dopaminergic system in the olfactory bulb (OB). Considering the genetic, neurophysiological, and pathological evidence that PD patients develop OD, in 1999, Hawkes and colleagues proposed that PD could be a primary olfactory disorder

[19].

In 2003, a study by Braak and colleagues provided a possible explanation for OD in PD patients. Examining the progression of the dissemination of α-synuclein pathology in postmortem brains, they found that in addition to the dorsal motor nuclei of the vagus (DMV) and glossopharyngeal nerves, the OB and anterior olfactory nucleus (AON) were among the first sites at which α-synuclein pathology is found in PD patients

[20].

In 2004, Huisman and colleagues studied the OBs of 10 PD patients and 10 controls. They identified a 100% increase in dopaminergic cells in the patients, suggesting that dopamine could be responsible for OD in PD

[21]. In 2008, the same authors conducted a study involving 20 PD patients and 19 controls. However, their findings differed, as they only observed a significant increase in these cells in females but not males. This suggests that OD cannot be solely explained by dopaminergic alterations in this brain structure, and other mechanisms must be involved

[22].

In 2007, Hawkes and colleagues proposed the “dual-hit hypothesis for Parkinson’s disease”

[23] based on the findings of Braak and colleagues

[20]. This hypothesis postulates that a neurotropic pathogen, such as a virus or toxins, enters the brain via two distinct pathways: the nasal route and the enteric nervous system plexuses. In the first pathway, the pathogen causes damage to the OB and then spreads toward the temporal lobe. In the second pathway, the pathogen propagates retrogradely from the enteric nervous system plexuses through the vagus nerve to reach the DMV in the brainstem. From there, it can spread to the midbrain, causing damage to the Substantia Nigra pars compacta (SNc), responsible for the motor symptoms characteristic of PD.

In 2008, Doty reviewed the plausibility of the olfactory vector hypothesis of neurodegenerative disease, which aligns with the dual-impact hypothesis for PD, suggesting that a xenobiotic agent enters the brain via the olfactory mucosa and then spreads to other brain structures

[9]. This hypothesis also applies to AD and arises from Roberts’ proposal (1986) that the disease could be caused by an agent that enters via this route, such as aluminosilicates

[24].

Although several previous studies suggested the possibility that OD precedes motor symptoms in PD patients, a study that provided more significant evidence in this regard was carried out by Ross and colleagues and published in 2008. This study assessed and followed the olfactory function of 2267 men without clinical PD for eight years. During this period, 35 cases were diagnosed with PD. It was found that those who had scored lower on the smell identification test had a higher risk of developing PD within the following four years

[4].

Considering the broad evidence that most PD patients develop OD, in 2015, it was integrated as a symptom within the clinical diagnostic criteria for Parkinson’s disease by the Movement Disorder Society (MDS)

[25]. In 2022, a study by Borghammer and colleagues provided evidence that does not support the dual-hit hypothesis of PD; after analyzing a dataset of 302 postmortem brains with Lewy pathology, they found evidence of cases in which the lower brainstem or peripheral autonomic nervous system was affected, but without Lewy pathology in the OB

[26]. Their findings support the α-Synuclein Origin site and Connectome (SOC) model proposed by the same author

[27].

The SOC model proposes that α-synuclein pathology can originate in two sites: (1) the OB or amygdala and (2) in the enteric nervous system. However, unlike the dual-hit hypothesis of PD, α-synuclein pathology does not co-occur in both regions. The first subtype is referred to as the brain-first subtype, while the second is the body-first subtype. In the brain-first subtype, α-synuclein pathology mainly spreads ipsilaterally, since most brain connections are of this type. Conversely, in the body-first subtype, dissemination occurs bilaterally, since the innervation of the enteric system by the vagus and parasympathetic nerves overlaps laterally. Therefore, the DMV would be bilaterally affected, leading to subsequent dissemination, and also in a bilateral way, to other brain regions, such as the basal ganglia

[26].

According to the SOC model, OD is more related to the body-first subtype because in the brain-first subtype, with the damage of only one side of the olfactory-related structures, the contralateral structures could perform the olfactory function. On the other hand, since both sides are affected in the body-first subtype, there is no possible compensation

[26].

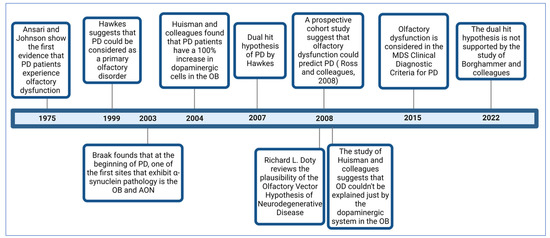

Figure 1 illustrates some of the most critical studies contributing to the comprehension of OD in PD.

Figure 1.

Timeline with some of the most important studies related to the comprehension of OD in PD.

4. Prevalence of Olfactory Dysfunction and Its Role in Diagnosis and as a Marker of PD Progression

Nowadays, it is indisputable that most patients with idiopathic and familial PD develop OD. The prevalence of this symptom was estimated in a multicenter study with patients from Germany, Australia, and the Netherlands. It was reported that, out of 400 patients with the disease, only 3.3% were normosmic. In contrast, 45.0% had anosmia, and 51.7% hyposmia. Additionally, considering the age-based norms (i.e., the olfactory capacities of people without any neuropathology according to their age group), it was found that 74.5% had some impairment of their olfactory function

[15].

Additional prospective longitudinal studies have been conducted to clarify the role of OD in the prodromal period of PD. Among these studies, in 2007, a study by Haehner and colleagues followed a group of 30 patients with idiopathic hyposmia. After four years, 7% had developed IPD, so the authors considered that this sign could be the first of this disease

[28]. On the other hand, in 2018, in a study by Haehner and colleagues, 474 patients with idiopathic olfactory loss were followed, and on average, 10.9 years later, 45 of them (9.8%) received a diagnosis of PD

[29]. Considering the above, OD could be an early biomarker of PD and, therefore, be valuable in assisting in the early diagnosis of PD

[30].

In addition, OD, in combination with other symptoms, could increase their value as early biomarkers of PD. For instance, a recent study provides evidence that individuals with isolated RBD can exhibit OD and dysprosody, a decreased pitch variation during speech (monopitch) when the nigrostriatal pathway is still intact

[31].

Early diagnosis would allow for neuroprotective treatment before further cerebral involvement occurs

[32], considering that by the time the motor symptoms appear, more than 60% of dopaminergic neurons in the nigrostriatal pathway have already undergone neurodegeneration

[33]. Additionally, detecting OD in the early stages can be helpful in differential diagnosis, considering that OD is milder in other Parkinsonian syndromes such as drug-induced Parkinsonism, MSA, PSP, and Cortico-basal Degeneration (CBD)

[30][34][30,34].

Furthermore, whether OD correlates with the progression of PD has been investigated. A review study by Fullard and colleagues suggests that OD is not a useful biomarker since no significant association has been found between these variables

[30]. However, a recent systematic review that included nine longitudinal studies that followed patients for an average of 38 months found that olfactory capacity decreased over time, deteriorating more rapidly in the early stages of the disease, suggesting a possible relationship with the progression of PD

[35]. On the other hand, another study showed an association between OD and a faster progression of PD

[36]. Regarding gender, although a study did not find differences between men and women with PD in odor identification

[37], in another study, men showed poorer olfactory performance

[38].

5. Assessment of the Olfactory System in Patients with PD

Psychophysical tests designed to assess olfactory function allow the measurement of three main olfactory domains: odor identification, threshold, and discrimination. In identification tests, the subject must smell an odorant and then respond to what it smells like, choosing from a series of written response options. The number of correct responses is used to evaluate the subject’s performance

[39].

Odor identification is the olfactory domain more used for assessing OD in PD

[40]. Among the most used tests for evaluating identification are The University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test (UPSIT), developed by Doty and colleagues, consisting of 40 items

[41], and its abbreviated version of 12 items called the Brief Smell Identification Test (B-SIT). Another commonly used test is the “Sniffin’ Sticks” Test, which in addition to identification, assesses threshold and discrimination. The test also yields a total score known as the TDI (Threshold, Discrimination, Identification)

[42].

Threshold tests evaluate two aspects, absolute threshold and recognition threshold. The former refers to the lowest odorant concentration that a person can detect. In contrast, the recognition threshold refers to the minimum amount of the odorant that a person can identify or recognize

[43]. In these tests, the participant compares the intensity of two or more stimuli, one odorant and one without odor, instead of indicating whether they perceive an odor. Recognition thresholds are measured similarly, but the subject must identify the specific smell. These forced-choice procedures are less prone to response bias

[43]. For evaluating odor discrimination, it is not necessary for the participant to identify the odor, but rather to have the ability to differentiate between different odors. For example, two odoriferous stimuli are presented, and the subject has to answer as to whether they smell similar or different

[39].

6. The Role of α-Synuclein and Its Aggregates in the Pathophysiology of PD

α-synuclein is a protein composed of 140 amino acids with a molecular weight of 14 kDa, encoded by the

SNCA gene and located on chromosome four in humans

[44][45][44,45]; it is found in axons and presynaptic terminals

[46]. Evidence suggests that it is involved in functions such as transporting and filling synaptic vesicles, releasing neurotransmitters in the synapse, and plasticity mechanisms

[47][48][47,48].

Although the presence of α-synuclein is not pathological, it can play a role in certain conditions known as synucleinopathies, including PD, dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), and MSA. In these pathologies, the protein can misfold and combine with other molecules to form abnormal aggregates called Lewy bodies (LBs) that have a globular shape and are located in the cell body, or Lewy neurites (LNs), which have a thread-like shape and are found in axons or dendrites; these are both difficult to eliminate via mechanisms such as the Autophagic-Lysosomal Pathway (ALP)

[20]. LBs and LNs can affect cellular functioning through processes such as the disruption of axonal transport, synaptic dysfunction, mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, endoplasmic reticulum stress, or ALP dysregulation

[49][50][49,50].

Even though the loss of dopaminergic neurons in the SNc has been considered the hallmark of PD, the study by Braak and colleagues provided evidence that other brain areas are affected before this brain region. In Stage 1, α-synuclein pathology is observed in the OB and AON, as well as in the motor nuclei of the glossopharyngeal and vagus nerve. Stage 2 encompasses the medulla oblongata and pontine tegmentum. Stage 3 primarily manifests in the SNc of the midbrain. Stage 4 involves the basal forebrain and neocortex. Finally, stages 5 and 6 affect the neocortex, including sensory association cortices, the prefrontal cortex, and the premotor cortex

[20]. It is estimated that the stages proposed by Braak apply to up to 80% of cases

[51].

It is worth noting that Braak and colleagues indicate that the progression of α-synuclein pathology extends from two points: (1) the brainstem, with an ascending progression, and (2) from the OB and AON, to reach other structures related to the olfactory system

[20]. Considering that most PD patients present with OD, it has been suggested that this symptom could be due to damage to these structures

[20].

7. Neuroanatomical Alterations in PD Patients

To understand the mechanisms underlying OD in PD, evaluations have been carried out in vivo in patients using functional and structural neuroimaging and histological studies in postmortem patients. The following sections address some of the most relevant findings found in the structures related to the olfactory system that could contribute to olfactory loss in PD patients.

7.1. Olfactory Epithelium

The human olfactory system starts in the olfactory epithelium on the roof of the nasal cavity. This region contains the endings of olfactory sensory neurons (OSNs), which are bipolar neurons with cilia on the apical dendrite, where olfactory receptors are located. These receptors are G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) to which odorant molecules bind. The axons of the OSNs form the olfactory nerve, which crosses the cribriform plate of the ethmoid bone and synapses with second-order neurons, mitral, and tufted cells. The olfactory epithelium is pseudostratified columnar and, in addition to OSNs, contains basal cells, which are stem cells, and sustentacular or supporting cells

[52].

In a study, the olfactory epithelium was evaluated to determine the presence of α-, β- and γ-synucleins in patients with Alzheimer’s disease, DLB, MSA, PD, and patients without these diseases. Among the different synucleins, α-synuclein was the most common type in the olfactory epithelium, primarily located in OSNs and basal cells. However, patients with the diseases did not have higher levels of this protein than controls. The authors suggest that this protein could be involved in the neuroplasticity of OSNs

[53].

Another study found that six out of eight patients with PD had LBs in OSNs

[54]. In contrast, in the study by Witt and colleagues, no differences were found in the distribution or expression of α-synuclein in the olfactory epithelium of PD patients compared to controls

[55]. Although biopsies of the olfactory epithelium could be easily obtained and used to search for α-synuclein pathology as a possible support for the diagnosis of PD, previous studies have suggested that due to the variability in the presence of this protein, the olfactory epithelium does not seem to be a viable option for this purpose

[56].

7.2. Olfactory Bulb

The OB is the first station of olfactory processing. It is an extension of the telencephalon composed of six distinct layers. The layers, from outer to inner, are called the nerve layer, glomerular layer (where glomeruli localize, comprising the endings of OSNs that make synapses with the apical dendrites of mitral and tufted cells, and dendrites of interneurons called periglomerular cells), the external plexiform layer (where tufted cell bodies are found), the mitral cell layer (which consists of bodies of mitral cells), the internal plexiform layer, and the granule cell layer, consisting of granule cells

[52].

One of the early findings in the research of the OB in nine PD patients was the presence of LBs in mitral cells

[57]. In one study, the presence of LBs and LNs was reported in structures such as the OB, AON, and the olfactory tract before being observed in the SNc

[58]. The observations of Braak and colleagues provided further support for these findings, as they documented the presence of these aggregates in the OB after stage I of their staging of PD pathology

[20]. Additional evidence has confirmed these aggregates’ presence in the OB

[59][60][61][59,60,61]. According to Borghammer and colleagues, as reported by Braak and colleagues, Lewy pathology could start in the OB and may also reach the OB via its spread from the locus coeruleus

[26].

Regarding the number of neurons in the OB, initially, Huisman and colleagues reported a 100% increase in dopaminergic neurons

[21]. However, upon doubling the sample size, this difference was only observed in females rather than men

[22]. In another study of six subjects with PD, more dopaminergic periglomerular neurons were observed than in the controls

[60]. On the other hand, Cave and colleagues did not find changes in the number of tyrosine hydroxylase-expressing neurons in the OB of male PD patients

[62].

At a general level, without distinguishing neuronal types, a decrease in neuronal density in the OB was found in a sample of seven PD patients

[63]. In another study, a significant reduction in mitral and tufted cells and Calretinin-positive interneurons was observed

[62]. Additionally, in a study conducted by Zapiec and colleagues in five patients with PD and six controls, it was found that PD patients may have fewer glomeruli, which may also be smaller than controls

[64].

Several studies using MRI have been carried out to determine whether there are changes in the volume of the OB in PD patients. A meta-analysis of six case–control studies suggested that the volume of both OBs in PD patients is smaller than in healthy controls

[65]. Furthermore, it was found that the volume of the right OB was larger in these patients. A smaller volume was also observed in a subsequent study not included in this analysis

[66]. However, in another later study using stereological methods, no significant differences were found

[61].

Based on the study by Pearce and colleagues

[63], Brodoehl and colleagues suggested that PD patients may have a smaller OB size due to a significant decrease in the number of neurons

[67]. A recent study analyzed the possible association between α-synuclein pathology and neuronal loss in the OB. According to the results, no significant reduction in Neu-N-positive neurons was found as the α-synuclein density increased

[61]. Moreover, it is worth noting that the same study showed an increase in astrogliosis and microgliosis in PD patients compared to controls, mainly in men

[61].

Considering that the density of α-synuclein pathology in the OB correlates with the severity of motor symptoms and cognition, and with α-synuclein pathology in other brainstem structures, including the parietal, temporal, and frontal lobes, it has been proposed that a biopsy from the OB tissue could be helpful as a diagnostic confirmation for PD

[68].

7.3. Anterior Olfactory Nucleus

The AON is a cortex-like structure comprising two layers. Some authors divide the AON into bulbar, retrobulbar, interpeduncular, and cortical regions

[69]. Its function facilitates reciprocal information exchange from the OB to the piriform cortex, between the OBs of both hemispheres and between the respective piriform cortices through the anterior commissure

[70].

In Braak’s staging, at stage one, α-synuclein inclusions are found in the AON and show severe damage at stage four

[20]. Additional studies have confirmed α-synuclein pathology in the AON of OD patients

[61][71][61,71]. Ubeda-Bañon and colleagues found LBs and LNs in the AON’s bulbar, retrobulbar, interpeduncular, and cortical regions. Specifically, these aggregates were found in cells expressing the substance P, parvalbumin, calbindin, and calretinin

[69]. In addition to neurons, the role of glial cells has also been investigated in this structure. α-synuclein inclusions were found in microglia, pericytes, and astrocytes, but not in oligodendrocytes. This may be due to glial cells participating in the uptake and degradation of α-synuclein

[3].

7.4. Olfactory Tract

The olfactory tract (OT) runs from the OB and extends posteriorly along the ventral part of the frontal lobe. It is composed of myelinated axons from mitral and tufted cells. The OT transmits information to the primary olfactory cortex, composed of the AON, olfactory tubercle, piriform cortex, anterior entorhinal cortex, peri amygdaloid cortex, and the anterior cortical nucleus of the amygdala

[70].

An imaging technique used to evaluate the OT is Diffusion Tensor Imaging (DTI), which uses fractional anisotropy (FA) to measure the structural integrity of axons through fiber density, myelin structure, and axonal diameter. FA is calculated based on the movement of water molecules within the cylindrical-shaped axons, which generates an anisotropic diffusion of water molecules within the axon

[72]. The FA value ranges from 0 to 1. A value of zero indicates the isotropic movement of water molecules, i.e., the cerebrospinal fluid, while a value of one represents anisotropic movement, i.e., the nerve fibers

[73]. In a study involving 23 patients with PD, a lower FA and a smaller OT volume were found compared to the controls

[74]. Another study utilized a high-resolution MRI sequence in combination with voxel-based statistical analysis and found a reduction in the volume of the OT in patients with PD

[75].

7.5. Piriform Cortex

The piriform cortex is part of the primary olfactory cortex and is crucial for perceiving and discriminating odors and olfactory memory

[76]. It is also responsible for processing complex mixtures of synthetic odorants and short-term olfactory habituation

[76]. As part of the paleocortex, it comprises three layers. Layer I, the molecular and outermost layer, is where axon terminals from tufted and mitral cells synapse; layer II is densely populated by pyramidal neurons and semilunar cells; and layer III is composed of polymorphic cells

[77][78][77,78]. An fMRI study showed that the right piriform cortex was more activated than the left while judging the familiarity of an odor

[79]. Histological analysis has demonstrated the presence of LBs in the Piriform cortex

[80]. Using Voxel-Based Morphometry (VBM), a smaller Gray Matter Volume (GMV) was found in the right piriform cortex of patients with PD

[75]. Additional studies have found that the smaller the volume of this area (atrophy), the worse the olfactory performance

[81][82][83][81,82,83].

7.6. Hippocampus

The hippocampus is an elongated structure that is wider in the anterior portion and becomes narrower in the posterior. It is in the medial part of the temporal lobe, adjacent to the lateral ventricles, and is approximately 4 to 4.5 cm long. It can be divided into the head, body, and tail

[84]. The hippocampus receives input from the piriform cortex

[85], but the primary source of information comes from the entorhinal cortex via the perforant pathway, which reaches the dentate gyrus. Then, this structure forms a synapse with the CA3 region through the mossy fibers, and from there, forms a synapse with the CA1 region through the Schaffer collateral pathway; it finally sends efferent projections to the entorhinal cortex, completing the classical trisynaptic circuit of the hippocampus

[86].

Although the hippocampus is primarily known for its role in learning and memory, it also participates in the central processing of odors

[87]. Together with the amygdala, it is considered part of the limbic olfactory pathway

[71]. According to the Braak stages, this structure is affected by α-synuclein pathology in stages three or four

[88]. Using fMRI, it was observed that hyposmic patients with PD showed a decrease in its activation

[89].

The volume of this structure was evaluated in 18 patients with PD and compared to 18 normosmic controls. A lower volume was found in both hemispheres in patients with PD and hyposmia, being more pronounced in the body subfields. Furthermore, this was correlated positively with scores obtained in an odor identification test

[87]. In a study by Bohnen and colleagues, selective hyposmia was investigated, in which individuals had difficulty identifying some specific odors but not others. This study revealed selective hyposmia for dill pickle, banana, and licorice. Additionally, using Positron Emission Tomography (PET) within the same study, dopamine transporter binding was measured in the ventral and dorsal striatum, amygdala, and hippocampus, finding a correlation between the dopamine binding mainly in the hippocampus and selective hyposmia. The authors interpreted these findings as suggesting that the dopaminergic innervation of the hippocampus is implicated in the higher-level cognitive processes required for the odor identification task

[88].

7.7. Orbitofrontal Cortex

The orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) is part of the neocortex and gets its name from its location above the eye sockets. It has been considered a secondary olfactory cortex since it participates in olfactory information processing

[70] and has functions in olfactory recognition memory

[90]. In healthy subjects, it has been shown that the medial OFC cortical thickness is positively related to olfactory performance

[91][92][91,92]. Specifically, the right OFC has been associated with the conscious perceptual experience of odors

[93]. At the same time, the left has been implicated in evaluating odors in terms of their pleasantness or unpleasantness, also known as hedonic odor judgment

[94]. Using VBM, a decrease in volume has been observed in subjects with anosmia without neurodegenerative diseases

[95].

Employing electroencephalography, it was discovered that odor recognition deficits in PD are related to reduced activation in the OFC

[96]. It has also been reported that a more significant loss of gray matter in this area is associated with worse olfactory function in patients with PD

[81]. However, in an additional study conducted on 20 patients with PD, no association was found between these variables

[97]. In a study of 24 patients with PD, DTI was used to evaluate the relationship between OD and white matter integrity through fractional anisotropy (FA) in central areas of the olfactory system. The results indicated that patients with OD had lower FA values in the OFC, particularly in the areas adjacent to the straight gyrus

[98].

The study by Silveira-Moriyama and colleagues found α-synuclein pathology in the OFC in patients with PD

[80]. One study shows that if α-synuclein pathology affects the OFC, it is more likely to be diagnosed as clinical PD. However, if the pathology is limited to the OB or OT, the diagnosis of this disease is less likely

[71].

7.8. Amygdala

The amygdala, also known as the amygdaloid complex, is a brain structure located in the ventral part of the brain, specifically in the anteromedial region of the temporal lobes. It consists of different nuclei divided into three groups: basolateral, central, and corticomedial. The latter connects with the olfactory system and is considered the primary olfactory cortex because it receives monosynaptic afferents from the OB. Specifically, it establishes connections with the cortical, medial, and periamygdaloid complex nuclei

[99].

In an analysis of 18 patients with PD, LBs were demonstrated in approximately 4% of neurons in the amygdala, mainly in the basolateral and cortical nuclei. In addition, a stereological analysis estimated a 20% reduction in volume. This reduction was primarily due to a 30% reduction in the volume of the corticomedial complex (central, medial, and cortical nuclei). The study suggests that the decline in the amygdala volume may be related to OD in patients with PD, as the cortical nucleus has essential connections with the OB

[100].

An additional MRI study with 115 PD patients with PD and 78 healthy controls found reduced GMV. However, there were no significant differences in the volume of the amygdala nuclei

[101]. By using the resting-state functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (rsfMRI) technique, an imaging technique performed while the subject is not engaged in an explicit task, it was determined that, in patients with PD, certain regions of this structure, such as the left centromedial cortex, left and right basolateral, and left superficial, had reduced connectivity with several areas of the brain, including the olfactory cortex. The same study found a negative correlation between the severity of anosmia and the functional connectivity of the different subregions of the amygdala

[101].

An additional report using rsfMRI found that patients with severe hyposmia exhibit altered functional connectivity between the amygdala and other brain regions, such as the inferior parietal lobe and the fusiform and lingual gyrus

[102]. Morphometric analysis using MRI found positive correlations between olfactory performance and GMV in the right amygdala in moderately advanced PD patients

[82]. Chen and colleagues found a smaller volume of gray matter in the amygdala in these patients

[75]. An additional study also found a reduction in gray matter in the right amygdala

[103].

7.9. Cerebellum

The cerebellum is in the posterior cranial fossa and comprises a medial structure called the vermis and the lateral hemispheres. Although it has traditionally been attributed to motor functions, it is also known to play cognitive and sensory roles

[104]. In 1998, a study by Sobel and colleagues was the first to demonstrate the involvement of this structure in the olfactory system

[105]. Using fMRI and an olfactory task, the researchers found a negative relationship between odorant concentration and airflow volume, with activation in the posterior part of the cerebellar hemispheres, specifically in the inferior semilunar lobule, superior semilunar lobule and the posterior part of the quadrangular lobule. This activation was positively correlated with the concentration of the presented odor, suggesting that the cerebellum may participate in a feedback mechanism to regulate airflow volume based on odor concentration. Additional fMRI studies found cerebellar activation in response to olfactory stimulation

[106][107][108][109][106,107,108,109]. However, it should be noted that the pathway by which olfactory information reaches the cerebellum and its specific function in this sensory system has not yet been determined

[109][110][109,110].

Considering that a decrease in the cortical gray matter was observed in subjects with anosmia

[95][111][95,111], the cerebellum may be involved in OD in patients with pathologies primarily affecting the cerebellum. For example, it has been observed that patients with spinocerebellar ataxias exhibit OD

[112][113][112,113]. In the case of PD, Sobel and colleagues showed that besides the odor identification impairment, these patients also had altered olfactomotor functions, as a significant decrease in airflow rate during sniffing was detected. The authors suggested that this alteration could be one of the reasons for OD in PD, given that sniffing, as a fine motor process, could be controlled by the cerebellum

[114].

Moreover, another study showed that patients with unilateral cerebellar lesions had an impairment regarding the identification of odors using the nostril contralateral to the lesion, suggesting a contralateral connection between each nasal cavity and a cerebellar hemisphere. Additionally, they displayed deficiencies in olfactomotor abilities, as a lower volume and sniffing speed were detected compared to the controls

[115].