The stimulator of interferon genes (STING) is an adaptor protein involved in the activation of IFN-β and many other genes associated with the immune response activation in vertebrates. STING induction has gained attention from different angles such as the potential to trigger an early immune response against different signs of infection and cell damage, or to be used as an adjuvant in cancer immune treatments. Pharmacological control of aberrant STING activation can be used to mitigate the pathology of some autoimmune diseases. The STING structure has a well-defined ligand binding site that can harbor natural ligands such as specific purine cyclic di-nucleotides (CDN). In addition to a canonical stimulation by CDNs, other non-canonical stimuli have also been described, but the exact mechanism of some of them has not been well defined.

- STING

- IFN

- antiviral response

1. Introduction

2. cGAS-STING Canonical Signaling Pathway

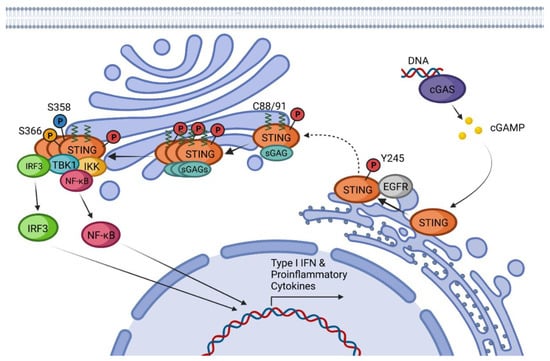

Among all cellular DNA sensors, cGAS is the best characterized and considered essential for developing an innate immune response against cytosolic dsDNA [25,26][25][26]. This protein can detect pathogenic DNA or DNA released from the mitochondria or the nucleus after cell damage, even when it has been oxidized [25,27][25][27]. dsDNA fragments of more than 20 base pairs (bp) can be recognized by cGAS in a sequence-independent manner inducing its dimerization in a 2:2 DNA/cGAS complex [25,28][25][28]. Fragments of DNA smaller than 20 bp are recognized by cGAS but are unable to induce dimerization and thus do not induce its activation, while long chains of dsDNA induce the formation of ladder-like structures that result in a stronger activation of this sensor [25,29][25][29]. After the formation of dimers or higher structures, cGAS changes conformation enabling its catalytic site activation (Figure 1) [25,28][25][28]. Once activated, cGAS can use adenine triphosphate (ATP) and guanine triphosphate (GTP) as substrates to produce the secondary metabolite cyclic cGAMP [25,26,28][25][26][28]. cGAMP produced by cGAS is a CDN that contains two phosphodiester bonds, one between the 2′-OH of GMP and the 5′-phosphate of AMP and the other between the 3′-OH of AMP and the 5′-phosphate of GMP (2′3′-cGAMP). This ring-structured molecule acts as a second messenger, binding and inducing STING activation. It has also been described that cGAMP can pass to neighboring cells through gap junctions in a process dependent on connexin 43 allowing contacting cells to trigger STING activation [30].

3. STING Non-Canonical Signaling Pathway

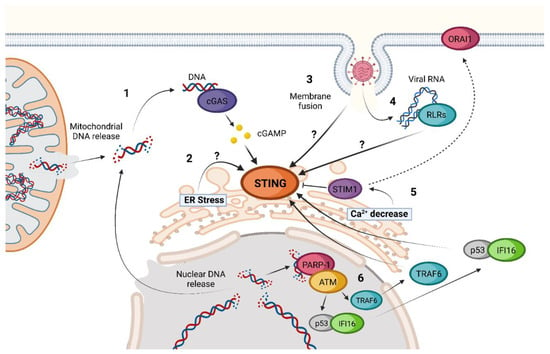

The activation of STING is possible even in the absence of cGAS, 2′3′-cGAMP, or other CDNs as inducers (Figure 2) [56,57][56][57]. Until now, different cGAS-independent mechanisms of STING activation have been described.

References

- Ishikawa, H.; Barber, G.N. STING is an Endoplasmic Reticulum Adaptor that Facilitates Innate Immune Signalling. Nature 2008, 455, 674–678.

- Barber, G.N. STING: Infection, Inflammation, and Cancer. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2015, 15, 760–770.

- Cai, H.; Imler, J. cGAS-STING: Insight on the Evolution of a Primordial Antiviral Signaling Cassette. Fac. Rev. 2021, 10, 54.

- Kranzusch, P.J. cGAS and CD-NTase Enzymes: Structure, Mechanism, and Evolution. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2019, 59, 178–187.

- Morehouse, B.R.; Govande, A.A.; Millman, A.; Keszei, A.F.A.; Lowey, B.; Ofir, G.; Shao, S.; Sorek, R.; Kranzusch, P.J. STING Cyclic Dinucleotide Sensing Originated in Bacteria. Nature 2020, 586, 429–433.

- Anastasiou, M.; Newton, G.A.; Kaur, K.; Carrillo-Salinas, F.J.; Smolgovsky, S.A.; Bayer, A.L.; Ilyukha, V.; Sharma, S.; Poltorak, A.; Luscinskas, F.W.; et al. Endothelial STING Controls T Cell Transmigration in an IFNI-Dependent Manner. JCI Insight. 2021, 6, e149346.

- Yu, Y.; Yang, W.; Bilotta, A.J.; Yu, Y.; Zhao, X.; Zhou, Z.; Yao, S.; Xu, J.; Zhou, J.; Dann, S.M.; et al. STING Controls Intestinal Homeostasis through Promoting Antimicrobial Peptide Expression in Epithelial Cells. FASEB J. 2020, 34, 15417–15430.

- Nazmi, A.; Mukhopadhyay, R.; Dutta, K.; Basu, A. STING Mediates Neuronal Innate Immune Response Following Japanese Encephalitis Virus Infection. Sci. Rep. 2012, 2, 347.

- Larkin, B.; Ilyukha, V.; Sorokin, M.; Buzdin, A.; Vannier, E.; Poltorak, A. Cutting Edge: Activation of STING in T Cells Induces Type I IFN Responses and Cell Death. J. Immunol. 2017, 199, 397–402.

- Walker, M.M.; Crute, B.W.; Cambier, J.C.; Getahun, A. B Cell-Intrinsic STING Signaling Triggers Cell Activation, Synergizes with B Cell Receptor Signals, and Promotes Antibody Responses. J. Immunol. 2018, 201, 2641–2653.

- Souza-Fonseca-Guimaraes, F.; Parlato, M.; de Oliveira, R.B.; Golenbock, D.; Fitzgerald, K.; Shalova, I.N.; Biswas, S.K.; Cavaillon, J.; Adib-Conquy, M. Interferon-Γ and Granulocyte/Monocyte Colony-Stimulating Factor Production by Natural Killer Cells Involves Different Signaling Pathways and the Adaptor Stimulator of Interferon Genes (STING). J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 10715–10721.

- Margolis, S.R.; Wilson, S.C.; Vance, R.E. Evolutionary Origins of cGAS-STING Signaling. Trends Immunol. 2017, 38, 733–743.

- Paludan, S.R.; Bowie, A.G. Immune Sensing of DNA. Immunity 2013, 38, 870–880.

- Yang, P.; An, H.; Liu, X.; Wen, M.; Zheng, Y.; Rui, Y.; Cao, X. The Cytosolic Nucleic Acid Sensor LRRFIP1 Mediates the Production of Type I Interferon Via a Beta-Catenin-Dependent Pathway. Nat. Immunol. 2010, 11, 487–494.

- Lin, B.; Goldbach-Mansky, R. Pathogenic Insights from Genetic Causes of Autoinflammatory Inflammasomopathies and Interferonopathies. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2022, 149, 819–832.

- Ishikawa, H.; Ma, Z.; Barber, G.N. STING Regulates Intracellular DNA-Mediated, Type I Interferon-Dependent Innate Immunity. Nature 2009, 461, 788–792.

- Li, X.; Wu, J.; Gao, D.; Wang, H.; Sun, L.; Chen, Z.J. Pivotal Roles of cGAS-cGAMP Signaling in Antiviral Defense and Immune Adjuvant Effects. Science 2013, 341, 1390–1394.

- Sun, Y.; Cheng, Y. STING Or Sting: cGAS-STING-Mediated Immune Response to Protozoan Parasites. Trends Parasitol. 2020, 36, 773–784.

- Webb, L.G.; Fernandez-Sesma, A. RNA Viruses, and the cGAS-STING Pathway: Reframing our Understanding of Innate Immune Sensing. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2022, 53, 101206.

- Nitta, S.; Sakamoto, N.; Nakagawa, M.; Kakinuma, S.; Mishima, K.; Kusano-Kitazume, A.; Kiyohashi, K.; Murakawa, M.; Nishimura-Sakurai, Y.; Azuma, S.; et al. Hepatitis C Virus NS4B Protein Targets STING and Abrogates RIG-I-Mediated Type I Interferon-Dependent Innate Immunity. Hepatology 2013, 57, 46–58.

- Rui, Y.; Su, J.; Shen, S.; Hu, Y.; Huang, D.; Zheng, W.; Lou, M.; Shi, Y.; Wang, M.; Chen, S.; et al. Unique and Complementary Suppression of cGAS-STING and RNA Sensing-Triggered Innate Immune Responses by SARS-CoV-2 Proteins. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 123.

- Corrales, L.; McWhirter, S.M.; Dubensky, T.W.; Gajewski, T.F. The Host STING Pathway at the Interface of Cancer and Immunity. J. Clin. Investig. 2016, 126, 2404–2411.

- Foote, J.B.; Kok, M.; Leatherman, J.M.; Armstrong, T.D.; Marcinkowski, B.C.; Ojalvo, L.S.; Kanne, D.B.; Jaffee, E.M.; Dubensky, T.W.; Emens, L.A. A STING Agonist Given with OX40 Receptor and PD-L1 Modulators Primes Immunity and Reduces Tumor Growth in Tolerized Mice. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2017, 5, 468–479.

- Demaria, O.; De Gassart, A.; Coso, S.; Gestermann, N.; Di Domizio, J.; Flatz, L.; Gaide, O.; Michielin, O.; Hwu, P.; Petrova, T.V.; et al. STING Activation of Tumor Endothelial Cells Initiates Spontaneous and Therapeutic Antitumor Immunity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 15408–15413.

- Yu, L.; Liu, P. Cytosolic DNA Sensing by cGAS: Regulation, Function, and Human Diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 170.

- Sun, L.; Wu, J.; Du, F.; Chen, X.; Chen, Z.J. Cyclic GMP-AMP Synthase is a Cytosolic DNA Sensor that Activates the Type I Interferon Pathway. Science 2013, 339, 786–791.

- Gehrke, N.; Mertens, C.; Zillinger, T.; Wenzel, J.; Bald, T.; Zahn, S.; Tüting, T.; Hartmann, G.; Barchet, W. Oxidative Damage of DNA Confers Resistance to Cytosolic Nuclease TREX1 Degradation and Potentiates STING-Dependent Immune Sensing. Immunity 2013, 39, 482–495.

- Decout, A.; Katz, J.D.; Venkatraman, S.; Ablasser, A. The cGAS-STING Pathway as a Therapeutic Target in Inflammatory Diseases. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2021, 21, 548–569.

- Luecke, S.; Holleufer, A.; Christensen, M.H.; Jønsson, K.L.; Boni, G.A.; Sørensen, L.K.; Johannsen, M.; Jakobsen, M.R.; Hartmann, R.; Paludan, S.R. cGAS is Activated by DNA in a Length-Dependent Manner. EMBO Rep. 2017, 18, 1707–1715.

- Wan, D.; Jiang, W.; Hao, J. Research Advances in how the cGAS-STING Pathway Controls the Cellular Inflammatory Response. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 615.

- Burdette, D.L.; Monroe, K.M.; Sotelo-Troha, K.; Iwig, J.S.; Eckert, B.; Hyodo, M.; Hayakawa, Y.; Vance, R.E. STING is a Direct Innate Immune Sensor of Cyclic Di-GMP. Nature 2011, 478, 515–518.

- Gürsoy, U.K.; Gürsoy, M.; Könönen, E.; Sintim, H.O. Cyclic Dinucleotides in Oral Bacteria and in Oral Biofilms. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2017, 7, 273.

- Devaux, L.; Sleiman, D.; Mazzuoli, M.; Gominet, M.; Lanotte, P.; Trieu-Cuot, P.; Kaminski, P.; Firon, A. Cyclic Di-AMP Regulation of Osmotic Homeostasis is Essential in Group B Streptococcus. PLoS Genet. 2018, 14, e1007342.

- Purcell, E.B.; Tamayo, R. Cyclic Diguanylate Signaling in Gram-Positive Bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2016, 40, 753–773.

- Randall, T.E.; Eckartt, K.; Kakumanu, S.; Price-Whelan, A.; Dietrich, L.E.P.; Harrison, J.J. Sensory Perception in Bacterial Cyclic Diguanylate Signal Transduction. J. Bacteriol. 2022, 204, e0043321.

- Ha, D.; O’Toole, G.A. C-Di-GMP and its Effects on Biofilm Formation and Dispersion: A Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Review. Microbiol. Spectr. 2015, 3, MB-2014.

- Cohen, D.; Melamed, S.; Millman, A.; Shulman, G.; Oppenheimer-Shaanan, Y.; Kacen, A.; Doron, S.; Amitai, G.; Sorek, R. Cyclic GMP-AMP Signalling Protects Bacteria Against Viral Infection. Nature 2019, 574, 691–695.

- Ergun, S.L.; Fernandez, D.; Weiss, T.M.; Li, L. STING Polymer Structure Reveals Mechanisms for Activation, Hyperactivation, and Inhibition. Cell 2019, 178, 290–301.e10.

- Shang, G.; Zhang, C.; Chen, Z.J.; Bai, X.; Zhang, X. Cryo-EM Structures of STING Reveal its Mechanism of Activation by Cyclic GMP-AMP. Nature 2019, 567, 389–393.

- Wang, C.; Wang, X.; Veleeparambil, M.; Kessler, P.M.; Willard, B.; Chattopadhyay, S.; Sen, G.C. EGFR-Mediated Tyrosine Phosphorylation of STING Determines its Trafficking Route and Cellular Innate Immunity Functions. EMBO J. 2020, 39, e104106.

- Dobbs, N.; Burnaevskiy, N.; Chen, D.; Gonugunta, V.K.; Alto, N.M.; Yan, N. STING Activation by Translocation from the ER is Associated with Infection and Autoinflammatory Disease. Cell Host Microbe 2015, 18, 157–168.

- Luo, W.; Li, S.; Li, C.; Lian, H.; Yang, Q.; Zhong, B.; Shu, H. iRhom2 is Essential for Innate Immunity to DNA Viruses by Mediating Trafficking and Stability of the Adaptor STING. Nat. Immunol. 2016, 17, 1057–1066.

- Ni, G.; Konno, H.; Barber, G.N. Ubiquitination of STING at Lysine 224 Controls IRF3 Activation. Sci. Immunol. 2017, 2, eaah7119.

- Fang, R.; Jiang, Q.; Guan, Y.; Gao, P.; Zhang, R.; Zhao, Z.; Jiang, Z. Golgi Apparatus-Synthesized Sulfated Glycosaminoglycans Mediate Polymerization and Activation of the cGAMP Sensor STING. Immunity 2021, 54, 962–975.e8.

- Mukai, K.; Konno, H.; Akiba, T.; Uemura, T.; Waguri, S.; Kobayashi, T.; Barber, G.N.; Arai, H.; Taguchi, T. Activation of STING Requires Palmitoylation at the Golgi. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11932.

- Zhang, C.; Shang, G.; Gui, X.; Zhang, X.; Bai, X.; Chen, Z.J. Structural Basis of STING Binding with and Phosphorylation by TBK1. Nature 2019, 567, 394–398.

- Yu, Y.; Liu, J.; Liu, C.; Liu, R.; Liu, L.; Yu, Z.; Zhuang, J.; Sun, C. Post-Translational Modifications of cGAS-STING: A Critical Switch for Immune Regulation. Cells 2022, 11, 3043.

- Li, Z.; Liu, G.; Sun, L.; Teng, Y.; Guo, X.; Jia, J.; Sha, J.; Yang, X.; Chen, D.; Sun, Q. PPM1A Regulates Antiviral Signaling by Antagonizing TBK1-Mediated STING Phosphorylation and Aggregation. PLoS Pathog. 2015, 11, e1004783.

- Tamura, T.; Yanai, H.; Savitsky, D.; Taniguchi, T. The IRF Family Transcription Factors in Immunity and Oncogenesis. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2008, 26, 535–584.

- Balka, K.R.; Louis, C.; Saunders, T.L.; Smith, A.M.; Calleja, D.J.; D’Silva, D.B.; Moghaddas, F.; Tailler, M.; Lawlor, K.E.; Zhan, Y.; et al. TBK1 and IKKε Act Redundantly to Mediate STING-Induced NF-κB Responses in Myeloid Cells. Cell Rep. 2020, 31, 107492.

- Zhu, Q.; Man, S.M.; Gurung, P.; Liu, Z.; Vogel, P.; Lamkanfi, M.; Kanneganti, T. Cutting Edge: STING Mediates Protection Against Colorectal Tumorigenesis by Governing the Magnitude of Intestinal Inflammation. J. Immunol. 2014, 193, 4779–4782.

- Gui, X.; Yang, H.; Li, T.; Tan, X.; Shi, P.; Li, M.; Du, F.; Chen, Z.J. Autophagy Induction Via STING Trafficking is a Primordial Function of the cGAS Pathway. Nature 2019, 567, 262–266.

- Zhang, R.; Kang, R.; Tang, D. The STING1 Network Regulates Autophagy and Cell Death. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 208.

- Liu, D.; Wu, H.; Wang, C.; Li, Y.; Tian, H.; Siraj, S.; Sehgal, S.A.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Shang, Y.; et al. STING Directly Activates Autophagy to Tune the Innate Immune Response. Cell Death Differ. 2019, 26, 1735–1749.

- Tian, Y.; Wang, M.; Zhao, J. Crosstalk between Autophagy and Type I Interferon Responses in Innate Antiviral Immunity. Viruses 2019, 11, 132.

- Srikanth, S.; Woo, J.S.; Wu, B.; El-Sherbiny, Y.M.; Leung, J.; Chupradit, K.; Rice, L.; Seo, G.J.; Calmettes, G.; Ramakrishna, C.; et al. The Ca2+ Sensor STIM1 Regulates the Type I Interferon Response by Retaining the Signaling Adaptor STING at the Endoplasmic Reticulum. Nat. Immunol. 2019, 20, 152–162.

- Petrasek, J.; Iracheta-Vellve, A.; Csak, T.; Satishchandran, A.; Kodys, K.; Kurt-Jones, E.A.; Fitzgerald, K.A.; Szabo, G. STING-IRF3 Pathway Links Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress with Hepatocyte Apoptosis in Early Alcoholic Liver Disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 16544–16549.

- Dunphy, G.; Flannery, S.M.; Almine, J.F.; Connolly, D.J.; Paulus, C.; Jønsson, K.L.; Jakobsen, M.R.; Nevels, M.M.; Bowie, A.G.; Unterholzner, L. Non-Canonical Activation of the DNA Sensing Adaptor STING by ATM and IFI16 Mediates NF-κB Signaling After Nuclear DNA Damage. Mol. Cell 2018, 71, 745–760.e5.

- Jønsson, K.L.; Laustsen, A.; Krapp, C.; Skipper, K.A.; Thavachelvam, K.; Hotter, D.; Egedal, J.H.; Kjolby, M.; Mohammadi, P.; Prabakaran, T.; et al. IFI16 is Required for DNA Sensing in Human Macrophages by Promoting Production and Function of cGAMP. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14391.

- Li, S.; Kong, L.; Yu, X. The Expanding Roles of Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress in Virus Replication and Pathogenesis. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2015, 41, 150–164.

- Choi, J.; Song, C. Insights into the Role of Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress in Infectious Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 3147.

- McGuckin Wuertz, K.; Treuting, P.M.; Hemann, E.A.; Esser-Nobis, K.; Snyder, A.G.; Graham, J.B.; Daniels, B.P.; Wilkins, C.; Snyder, J.M.; Voss, K.M.; et al. STING is Required for Host Defense Against Neuropathological West Nile Virus Infection. PLoS Pathog. 2019, 15, e1007899.

- Chen, Y.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Y.; Chiu, W.; Shen, M. The STIM1-Orai1 Pathway of Store-Operated Ca2+ Entry Controls the Checkpoint in Cell Cycle G1/S Transition. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 22142.

- Mekahli, D.; Bultynck, G.; Parys, J.B.; De Smedt, H.; Missiaen, L. Endoplasmic-Reticulum Calcium Depletion and Disease. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2011, 3, a004317.

- Wrighton, K. The STING Behind Dengue Virus Infection. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 16, 330.

- Ni, G.; Ma, Z.; Damania, B. cGAS and STING: At the Intersection of DNA and RNA Virus-Sensing Networks. PLoS Pathog. 2018, 14, e1007148.

- Franz, K.M.; Neidermyer, W.J.; Tan, Y.; Whelan, S.P.J.; Kagan, J.C. STING-Dependent Translation Inhibition Restricts RNA Virus Replication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E2058–E2067.

- Webb, L.G.; Veloz, J.; Pintado-Silva, J.; Zhu, T.; Rangel, M.V.; Mutetwa, T.; Zhang, L.; Bernal-Rubio, D.; Figueroa, D.; Carrau, L.; et al. Chikungunya Virus Antagonizes cGAS-STING Mediated Type-I Interferon Responses by Degrading cGAS. PLoS Pathog. 2020, 16, e1008999.

- Aguirre, S.; Maestre, A.M.; Pagni, S.; Patel, J.R.; Savage, T.; Gutman, D.; Maringer, K.; Bernal-Rubio, D.; Shabman, R.S.; Simon, V.; et al. DENV Inhibits Type I IFN Production in Infected Cells by Cleaving Human STING. PLoS Pathog. 2012, 8, e1002934.

- Ding, Q.; Cao, X.; Lu, J.; Huang, B.; Liu, Y.; Kato, N.; Shu, H.; Zhong, J. Hepatitis C Virus NS4B Blocks the Interaction of STING and TBK1 to Evade Host Innate Immunity. J. Hepatol. 2013, 59, 52–58.

- Sun, L.; Xing, Y.; Chen, X.; Zheng, Y.; Yang, Y.; Nichols, D.B.; Clementz, M.A.; Banach, B.S.; Li, K.; Baker, S.C.; et al. Coronavirus Papain-Like Proteases Negatively Regulate Antiviral Innate Immune Response through Disruption of STING-Mediated Signaling. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e30802.

- Aguirre, S.; Luthra, P.; Sanchez-Aparicio, M.T.; Maestre, A.M.; Patel, J.; Lamothe, F.; Fredericks, A.C.; Tripathi, S.; Zhu, T.; Pintado-Silva, J.; et al. Dengue Virus NS2B Protein Targets cGAS for Degradation and Prevents Mitochondrial DNA Sensing during Infection. Nat. Microbiol. 2017, 2, 17037.

- Lai, J.; Wang, M.; Huang, C.; Wu, C.; Hung, L.; Yang, C.; Ke, P.; Luo, S.; Liu, S.; Ho, L. Infection with the Dengue RNA Virus Activates TLR9 Signaling in Human Dendritic Cells. EMBO Rep. 2018, 19, e46182.

- Sun, B.; Sundström, K.B.; Chew, J.J.; Bist, P.; Gan, E.S.; Tan, H.C.; Goh, K.C.; Chawla, T.; Tang, C.K.; Ooi, E.E. Dengue Virus Activates cGAS through the Release of Mitochondrial DNA. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 3594.

- Liu, X.; Wei, L.; Xu, F.; Zhao, F.; Huang, Y.; Fan, Z.; Mei, S.; Hu, Y.; Zhai, L.; Guo, J.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein-Induced Cell Fusion Activates the cGAS-STING Pathway and the Interferon Response. Sci. Signal. 2022, 15, eabg8744.

- Holm, C.K.; Jensen, S.B.; Jakobsen, M.R.; Cheshenko, N.; Horan, K.A.; Moeller, H.B.; Gonzalez-Dosal, R.; Rasmussen, S.B.; Christensen, M.H.; Yarovinsky, T.O.; et al. Virus-Cell Fusion as a Trigger of Innate Immunity Dependent on the Adaptor STING. Nat. Immunol. 2012, 13, 737–743.

- Holm, C.K.; Rahbek, S.H.; Gad, H.H.; Bak, R.O.; Jakobsen, M.R.; Jiang, Z.; Hansen, A.L.; Jensen, S.K.; Sun, C.; Thomsen, M.K.; et al. Influenza A Virus Targets a cGAS-Independent STING Pathway that Controls Enveloped RNA Viruses. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 10680.

- Liu, Y.; Goulet, M.; Sze, A.; Hadj, S.B.; Belgnaoui, S.M.; Lababidi, R.R.; Zheng, C.; Fritz, J.H.; Olagnier, D.; Lin, R. RIG-I-Mediated STING Upregulation Restricts Herpes Simplex Virus 1 Infection. J. Virol. 2016, 90, 9406–9419.