Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Vítor Carvalho and Version 2 by Sirius Huang.

Blind people often encounter challenges in managing their clothing, specifically in identifying defects such as stains or holes. With the progress of the computer vision field, it is crucial to minimize these limitations as much as possible to assist blind people with selecting appropriate clothing.

- blind people

- clothing defect detection

- object detection

- deep learning

1. Introduction

Visual impairment, e.g., blindness, can have a significant impact on the psychological and cognitive functioning of an individual. Several studies have shown that vision impairment is associated with a variety of negative health outcomes and a poor quality of life [1][2][1,2]. Additionally, blindness currently affects a significant number of individuals, and thus it should not be assumed as a minor concern for society. According to a recent study, there are 33.6 million people worldwide suffering from blindness, which clearly shows the dimension of this population group [3].

The use of assistive technology can help in mitigating the negative effects of blindness and improve the quality of life of people who are blind. Although there has been a proliferation of smart devices and advancements in cutting-edge technology for blind people, most research efforts have been directed towards navigation, mobility, and object recognition, leaving aesthetics aside [4][5][6][4,5,6]. The selection of clothing and preferred style for different occasions is a fundamental aspect of one’s personal identity [7]. This has a significant impact on the way we perceive ourselves, and on the way we are perceived by others [7][8][7,8]. Nonetheless, individuals who are blind may experience insecurity and stress when it comes to dressing-up due to a lack of ability to recognize the garments’ condition. This inability to perceive visual cues can make dressing-up a daily challenge. In addition, blind people may have a higher probability of clothing staining and tearing due to the inherent difficulties in handling objects and performing daily tasks. In particular, detecting stains in a timely manner is crucial to prevent them from becoming permanent or hard to remove. Despite the promising potential of technological solutions in the future, significant challenges still need to be overcome. The lack of vision makes it challenging for these individuals to identify small irregularities or stains in the textures or fabrics of clothing, and they rely on others for assistance.

2. Defect Detection in Clothing

Defect detection in clothing remains a barely addressed topic on the literature. However, if the scope of the topic is expanded to the industry, some interesting works have been carried out, mainly regarding the fabric quality control in the textile industry. Such quality control approach still plays an important role in the industry, and can be an appealing starting point for defect detection in clothing with other purposes in sight [9][17]. Based on the aforementioned premise, a quick literature survey allows perceiving that machine vision based on image processing technology has replaced manual inspection, and allows for reducing costs and increasing the detection accuracy. An integral part of modern textile manufacturing is the automatic detection of fabric defects [10][18]. More recently, due to their success in a variety of applications, deep learning methods have been applied to the detection of fabric defects [11][19]. A wide range of applications were developed using convolutional neural networks (CNNs), such as image classification, object detection, and image segmentation [12][20]. Defect detection using convolutional neural networks can be applied to several different objects [13][14][15][21,22,23]. Comparatively to traditional image processing methods, CNNs can automatically extract useful features from data without requiring complex feature designs to be handcrafted [16][24]. Zhang et al. [17][25] presented a comparative study between different networks of YOLOv2, with proper optimization, in a collected yam-dyed fabric defect dataset, achieving an intersection over union (IoU) of 0.667. Another method, unsupervised, based on multi-scale convolutional denoising autoencoder networks, was presented by Mei et al. [18][26]. A particularity of this approach is the possibility of being trained with only a small number of defects, without label ground truth or human intervention. A maximum accuracy of 85.2% was reported from four datasets. A deep-fusion fabric defect detection algorithm, i.e., DenseNet121-SSD (Densely Connected Convolutional Networks 121-Single-Shot Multi-Box Detector), was proposed by He et al. [19][27]. By using a deep-fusion method, the detection is more accurate, and the detection speed becomes more efficient, achieving a mean average precision (mAP) of 78.6%. Later, Jing et al. [20][28] proposed a deep learning segmentation model, i.e., Mobile-Unet, for fabric defect segmentation. Here, a benchmark is performed with conventional networks on two fabric image databases, the Yarn-dyed Fabric Images (YFI) and the Fabric Images (FI), allowing to reach IoU values of 0.92 and 0.70 for YFI and FI, respectively. A novel model of a defect detection system using artificial defect data, based on stacked convolutional autoencoders, was then proposed by Han et al. [21][29]. Their method was evaluated through a comparative study with U-Net with real defect data, and it was concluded that actual defects were detected using only non-defect and artificial data. Additionally, an optimized version of the Levenberg–Marquardt (LM)-based artificial neural network (ANN) was developed by Mohammed et al. for leather surfaces [22][30]. The latter enables the classification and identification of defects in computer vision-based automated systems with an accuracy of 97.85%, compared with 60–70% obtained through manual inspection. Likewise, Xie et al. [23][31] proposed a robust fabric defect detection method, based on the improved RefineDet. Three databases were used to evaluate their study. Additionally, a segmentation network with a decision network was proposed by Huang et al. [24][32], with the reduced number of images needed to achieve accurate segmentation results being a major advantage. Furthermore, a deep learning model to classify fabric defects in seven categories based on CapsNet was proposed by Kahraman et al. [25][33], achieving an accuracy of 98.71%. Table 1 summarizes the main results of the aforementioned works, including the datasets used.Table 1. Literature overview on textile fabric defect detection, including the author, year, method, dataset, defect classes, and metrics.

| Author | Year | Method | Dataset | Defect Classes | Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hang et al. [17][25] | 2018 | DL object detection (YOLOv2) |

Collected dataset: 276 manually labeled defect images | 3 | IoU: 0.667 |

| Mei et al. [18][26] | 2018 | Multiscale convolutional denoising autoencoder network model | Fabrics dataset: ca. 2000 samples of garments and fabrics | - | Accuracy: 83.8% |

| KTH-TIPS | - | Accuracy: 85.2% | |||

| Kylberg Texture: database of 28 texture classes | - | Accuracy: 80.3% | |||

| Collected dataset: ms-Texture | - | Accuracy: 84.0% | |||

| He et al. [19][27] | 2020 | DenseNet-SSD | Collected dataset: 2072 images | 6 | mAP: 78.6% |

| Jing et al. [20][28] | 2020 | DL segmentation (Mobile-Unet) | Yarn-dyed Fabric Images (YFI): 1340 images composed in a PRC textile factory. |

4 | IoU: 0.92; F1: 0.95 |

| Fabric Images (FI): 106 images provided by the Industrial Automation Research Laboratory of the Department of Electrical and Electronic Engineering at Hong Kong University | 6 | IoU: 0.70; F1: 0.82 | |||

| Han et al. [21][29] | 2020 | Stacked convolutional autoencoders | Synthetic and collected dataset | - | F1: 0.763 |

| Mohammed et al. [22][30] | 2020 | A multilayer perceptron with a LM algorithm | Collected dataset: 217 images | 11 | Accuracy: 97.85% |

| Xie et al. [23][31] | 2020 | Improved RefineDet | TILDA dataset: 3200 images; only 4 classes were used from 8 in total, resulting in 1597 defect images. | 4 of 8 | mAP: 80.2%; F1: 82.1% |

| Hong Kong patterned textures database: 82 defective images. | 6 | mAP: 87.0%; F1: 81.8% | |||

| DAGM2007 Dataset: 2100 images | 10 | mAP: 96.9%; F1: 97.8% | |||

| Huang et al. [24][32] | 2021 | Segmentation network | Dark redfFabric (DRF) | 4 | IoU: 0.784 |

| Patterned texture fabric (PTF) | 6 | IoU: 0.695 | |||

| Light blue fabric (LBF) | 4 | IoU: 0.616 | |||

| Fiberglass fabric (FF) | 5 | IoU: 0.592 | |||

| Kahraman et al. [25][33] | 2022 | Capsule Networks | TILDA dataset | 7 | Accuracy: 98.7% |

Figure 1. Examples of defects from the TILDA dataset: (a) large oil stain in the upper right corner, and (b) medium-sized hole in the upper left corner.

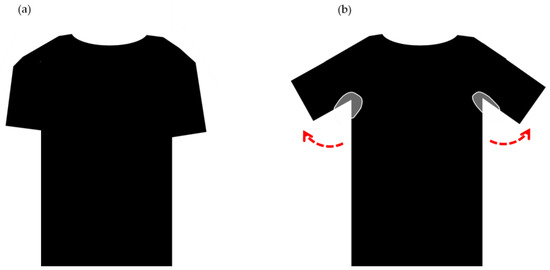

Figure 2.

Visibility of the defects on clothing: (

a

) imperceptible sweat stain and (

b

) visible sweat stain.