You're using an outdated browser. Please upgrade to a modern browser for the best experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Antonio Scarano and Version 2 by Lindsay Dong.

Dental implant-supported prostheses are a well-established rehabilitation treatment for partially or completely edentulous patients that restore function and esthetics while having long-term survival rates. The tissues surrounding osseointegrated dental implants are referred to as peri-implant tissues, consisting of soft and hard tissue parts. The soft tissue part forms following the placement of implant/abutment during the wound healing and is known as “peri-implant mucosa,” while the hard tissue part makes contact with the implant surface to ensure implant stability.

- dental implant

- evidence-based practice

- mucositis

- peri-implant disease

1. Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions

1.1. Peri-Implant Health

Healthy peri-implant tissues is a more objective definition of implant success that focuses on the biological and esthetic health of surrounding tissues in addition to the implant function rather than just implant survival. This is clinically assessed by:

-

Absence of clinical inflammatory signs;

-

No bleeding and suppuration on mild probing (0.25 N);

-

Stable probing depth compared to previous visits;

The physiological probing depth around implants cannot be determined since the absence of the periodontal ligament provides less resistance to probe insertion. Consequently, excessive force on probing can disrupt the integrity of the mucosa-abutment attachment and produce bleeding on healthy implants. As such, we could have peri-implant health on implants with reduced bone support, successfully treated implants, or implants positioned in a diminished alveolar crest [2][4].

The peri-implant mucosa section facing the implant consists of two compartments, a “coronal” compartment lined with the sulcular epithelium and a thin epithelial attachment, whereas the “apical” compartment contacts the connective tissue implant surface. Histologically, this mucosa contains a connective tissue core, often covered by orthokeratinized epithelium on its outer surface [1][3]. Therefore, after abutment placement, the mucosal height gradually stabilizes to 3–4 mm, with a 2 mm epithelium [3][5] (Figure 1).

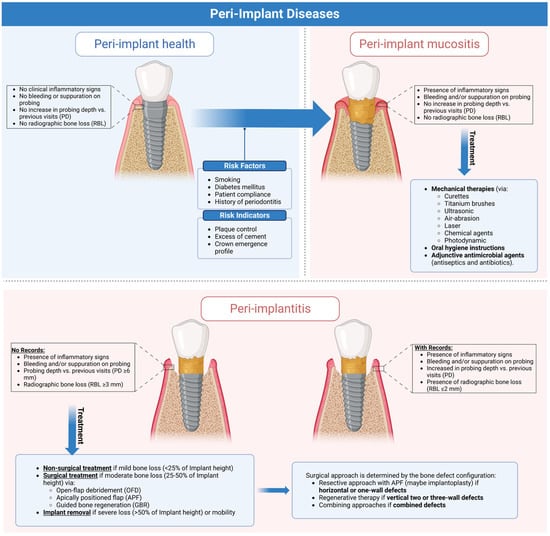

Figure 1. Graphical abstract illustrating the clinical characteristics of peri-implant health and diseases and current evidence-based approaches for managing peri-implant diseases. This figure was created using Biorender.com (https://app.biorender.com).

1.2. Peri-Implant Mucositis

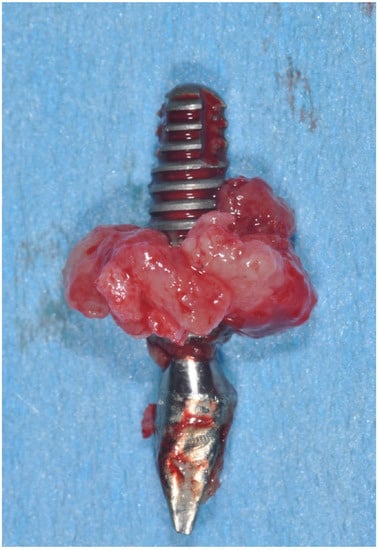

Peri-implant mucositis (Figure 2) is an inflammation in the peri-implant tissue that is clinically identified by bleeding and/or suppuration on probing without radiographic bone loss [4][6].

Figure 2.

Peri-implant mucositis; there is gingival inflammation around the implant unit.

Although a recognized cause–effect relationship exists between mucositis and plaque accumulation [5][7], reestablishing good oral hygiene could restore the clinical parameters and biochemical markers in the peri-implant crevicular fluid to normal. Even if implants have less plaque accumulation, they often show more inflammation and bleeding sites than teeth [6][8]. Histologically, the inflammatory lesion is found in the connective tissue, lateral to the epithelial barrier, and it is more extensive for advanced lesions (0.36 mm2) than in the early lesion (three weeks 0.14 mm2) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

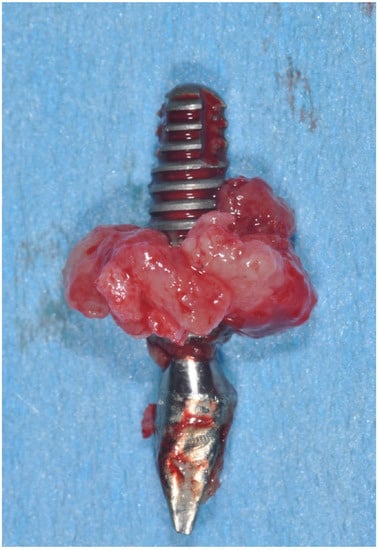

Peri-implant mucositis; inflammatory tissues induced by abutment loosening.

1.3. Peri-Implantitis

Peri-implant mucositis is an inflammation in the peri-implant soft tissues with a progressive loss in the supporting bone. It is clinically identified by bleeding and/or suppuration on probing, increased pocket depth compared to previous visits, and radiographic bone loss [7][9] (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Peri-implantitis; (

A

) Clinical signs. (

B

) Probing depth. (

C

) Peri-implant inflammatory tissue.

Standardized intraoral radiographs should be performed to monitor changes in bone levels around implants beginning with abutment placement, as crestal losses of more than 2 mm (physiological remodeling) from the baseline should be considered pathological [2][4]. When previous clinical or radiographic data are unavailable, the diagnosis should be confirmed by bleeding and/or suppuration on probing, a pocket depth greater than 6 mm, and more than 3 mm of radiographic bone loss (measured from the most coronal part of the marginal bone crest). Histologically, the inflammation becomes twice the size of the periodontal lesion (3.5 mm2 versus 1.5 mm2), extending to the bone crest and containing more neutrophils and lymphocytes B CD19+ than mucositis and more polymorphonuclear and macrophages than periodontitis [8][9][10,11] (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Clinical aspect of implant removed for peri-implantitis.

2. Epidemiology of Peri-Implant Diseases

Evaluation of the diseases’ epidemiological features aims to determine how frequently and why the disease arises. Such epidemiological data are used to assess and improve available disease-specific prevention approaches, which are often implemented to target the affected population [10][14]. As such, Derks et al. showed that the prevalence of peri-implant mucositis ranged from 19% to 65% and peri-implantitis from 1% to 47% [11][15]. However, Lee et al., in a meta-analysis, showed that the mean prevalence of peri-implant mucositis was 29.48% (implant-based) and 46.83% (subject-based), and the mean prevalence of peri-implantitis was 9.25% (implant-based) and 19.83% (subject-based) [12][16]. Moreover, Rakic et al. revealed in a meta-analysis that the peri-implantitis prevalence was 18.5% (implant-level) and 12.8% (patient-level) [13][17]; however, Dreyer et al. revealed in a meta-analysis that the peri-implantitis prevalence ranged from 1.1% to 85.0% (implant-level) and an incidence ranged from 0.4% (within three years) to 43.9% (within five years) [14][18].

Such variations in prevalence are due to methodological heterogeneity in reporting the peri-implant biological complications in studies, which limits attempts to estimate the true impact of peri-implant diseases globally; thus, that emphasizes the importance of fully adopting case definitions by the World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-implant Diseases (2017) for accurate prevalence estimation [15][19].

3. Risk Factors and Indicators

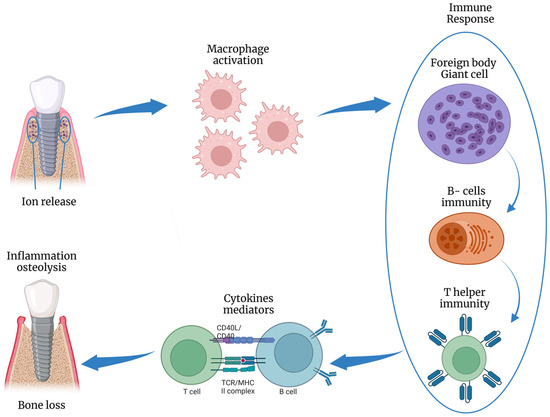

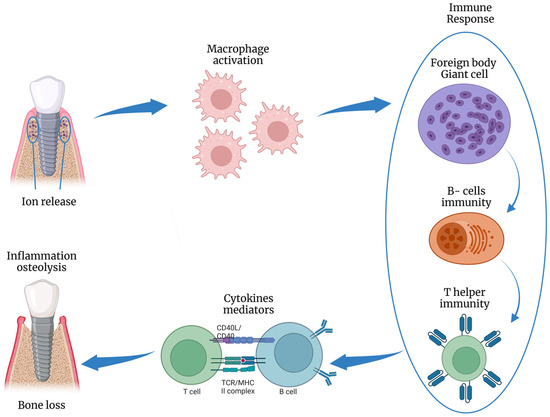

Risk factors are disease-causing agents usually established by longitudinal research, whereas risk indicators depend on cross-sectional investigations [16][20]. Several risk factors and risk indicators of peri-implant diseases are summarized in Figure 3. Smoking and diabetes are the most well-known systemic risk factors that have been reliably related to peri-implant disorders. Poor plaque control is a risk factor since it makes it difficult to reach the implant sites during oral hygiene, explaining the higher incidence of peri-implantitis in areas with limited access to oral hygiene (65%) compared to cleanable areas (18%) [17][25]. Excess cement retained around peri-implant soft tissues promotes plaque accumulation due to its rough surface [18][26], and its removal promotes the normalization of inflammation indices [19][27]. Thus, cemented prostheses without cement residues appear to have no increased risk of developing peri-implantitis compared to screw-retained prostheses (Figure 4). Adherence to oral hygiene instructions is also a risk factor, as Costa et al. [20][28] and Roccuzzo et al. [21][24] found that individuals who followed a regular maintenance program had a lower incidence of peri-implantitis (18% and 27%, respectively) than those who did not (43% and 47%). There is controversy about the minimum amount of keratinized mucosa around the implant; however, many observational studies indicated that keratinized mucosal deficiency (<2 mm) causes more discomfort in oral hygiene procedures, higher plaque levels, deeper pockets, and bleeding [22][23][29,30]. The presence of peri-implantitis has been associated with many gene polymorphisms (e.g., IL-1 gene) and osteoprotegerin (IL-6, and TNF7). In addition, Titanium and/or iron particles were identified in peri-implant tissue biopsies and inflammatory cells at peri-implantitis areas [24][31]. Titanium atoms may boost T-lymphocyte differentiation towards the osteoclastic pathway [25][32] and could alter microbial genetic expression via epigenetic DNA methylation [26][33] (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Schematic illustration of the inflammatory response to titanium ions release, inducing osteolysis. This figure was created using Biorender.com.

4. Prevention of Peri-Implant Diseases

With the increasing prevalence of peri-implantitis, and its irreversible condition with limited and expensive treatments, preventing peri-implant diseases is becoming paramount to decreasing its incidence and boosting implant success rates [27][28][48,49]. As such, The European Federation of Periodontology (EFP) established some recommendations for managing the primary risk factors of peri-implant diseases throughout implant workflow [27][48]. Proper personalized risk assessment for the individual patient is the primary key to these preventive measures, which aim to address and modify any relevant risk factors (either local or systemic) [28][49].

Such preventive measures begin before implant placement (“Primordial prevention”) by addressing the underlying risk factors that may induce disease development (e.g., preventing noncommunicable diseases (diabetes type-II) by healthy behavior promotion such as not smoking, increasing physical activity, and healthy diets) [28][49]. Once implant placement occurs, preventive measures (“Primary prevention”) are implemented to maintain the peri-implant tissues healthy over time and address any risk factors that may trigger disease onset, such as regularly controlling biofilm accumulation around implants and practically educating and motivating patients on oral hygiene measures). Then, early management and control of peri-implant mucositis should be implemented to prevent peri-implantitis progression (“Secondary prevention”) [28][49].