Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Rita Xu and Version 1 by Peshang Hama Karim.

European member states have high emission reduction potential. They send a strong signal to the rest of the world with their action or inaction on climate change. Yet, within the EU, national-level climate policies (NLCP) lag behind the EU Commission’s overall climate goals. Transparency of and accountability for climate action requires an integrative perspective.

- climate change

- climate impacts

- climate policy

- EU

- Public Attitudes

- Paris Agreement

1. Introduction

The European Union (EU) contributes significantly to global emissions, historically and currently. EU countries (EU-27) have been responsible for approximately 18% of global carbon dioxide emissions since the industrial revolution, mainly produced by the four most polluting countries in the EU—Germany, France, Italy, and Poland [1].

The EU continues to contribute significantly to global warming, although awareness and concern about climate change are widespread in European societies [2]. Additionally, the EU is considered a global leader in political commitment towards climate action [3]. This evolution in public concern and responsible governance coincides with growing knowledge about the impacts of climate change [4] and the increasing viability and affordability of technology to make sustainable transitions [5]. It seems that the stage is set; however, climate action is slow and incremental rather than rapid and transformative [6,7][6][7]. While many states make commitments to climate action, wresearchers have not seen the scale and speed of transformation that is necessary to keep the planet well under 2 °C of warming [8]. While the accusation by climate activists and the public that effective policy (and climate action) lags behind climate change impacts is common, there is a need for more empirical evidence to support this claim. The difference between commitment and action is referred to as ‘the knowledge–action gap’ and has led to a new sub-field of climate science called ‘climate action science’ [9].

Diverse countries within the EU are expected to work together to achieve the aspirations of the European Green Deal—perhaps the biggest social and economic transformation in human history in such a short time. There is a lack of research examining the connections between domains and factors enabling and inhibiting climate action and comparing these relationships over time in the EU [10].

2. Climate Change Impacts—The Trends

The frequency and severity of climate and weather extreme events have increased over the years [12][11]. Events such as wildfires, extreme precipitation, and heat on land and in the ocean are more and more significant. The European Union is increasingly at risk of extreme climate events such as heat-related human mortality, marine and terrestrial ecosystem disruptions, water scarcity, losses in crop production, and risks to infrastructure [13][12].3. Climate Change Policy—The Trends

The EU has pledged to achieve net-zero greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 2050. To do so, the governments of the European countries have committed themselves to climate change mitigation policies. Mitigation policies seek to prevent or reduce GHGs that cause climate change while climate change adaptation policies anticipate the adverse effects of climate change and seek to minimise potential damages. Since the Kyoto Protocol in the early 2000s, climate policies have sustained the trend in emission reduction. Emissions have been driven down by national and EU-level climate policies targeting energy efficiency and increasing the use of renewable energy fields [14][13]. In general, progress has continued in the EU since the Paris Agreement, with emissions decreasing [15][14]. However, some disparities at the macro-regional level can be observed, with individual member states showing less support for climate policies [16][15]. Increasing the effort is required to reach the 2050 target [17][16]. A recent study showed that in order to meet the European Commission’s objectives for renewable energy, the current progress of EU member states needs to double [18][17].4. Public Attitudes towards Climate Change—The Trends

Studies show that the level of concern for climate change has increased in the EU since the Paris Agreement [19][18]. Jakučionytė-Skodienė and Liobikienė [20][19] show that on a 10-point scale, the average climate change concern in EU countries between 2015 and 2019 has increased from 7.24 to 7.86, and they hypothesise that the evolution could have been triggered by the discussions around the Paris Agreement, as well as by the movement against climate change and extreme weather events. Moreover, the study highlights the increased feeling of personal responsibility within the EU-27 since the Paris Agreement, which increased by 1.7 times between 2015 and 2019. Studies, however, demonstrate that concern for climate change is not uniform throughout Europe, with countries such as Portugal, Spain, and Germany showing a higher level of concern than Ireland or the Eastern European countries [21][20]. Given this disparity, it is important to study both components together at the EU level and at the regional level.5. Climate Change Impacts and Public Attitudes towards Climate Change

Of the articles we identified in our searches, most investigated pairwise relationships between these two domains, such as the relationship between climate change impacts and public attitudes towards climate change. For example, Arıkan and Günay [22][21] tested whether perceived threats from climate change influence climate change concern and found that both the planetary threat and personal threat have substantive effects on climate change concern, with personal threat exerting a greater influence on climate change concern than the planetary threat, with a stronger effect in high-income countries than low-income ones.6. Climate Change Impacts and Climate Change Policy

Another pairwise relationship examined in the literature is the dyad between climate change impacts and climate policies. Climate policy can include policies that mitigate emissions, adapt to climate change, or (ideally) do both. Aguiar et al. [23][22] examined 147 local adaptation strategies in Europe and found that the key triggers for policy action (adaptation) were the increasing frequency of extreme weather events as well as incentives via research projects and implementation of EU policies. This demonstrates a connection between climate change impacts and climate policy in the EU, with the main barriers to climate change adaptation policy being uncertainty, insufficient resources/capacity, and insufficient political commitment.7. Public Attitudes towards Climate Change and Climate Change Policy

Other research has explored the relationship between public attitudes towards climate change and climate policy. Public concern about climate change is a crucial variable influencing public support for climate action [22][21]. Events that are understood to be impacts of climate change can shape human attitudes, understanding, and risk assessment of global environmental changes [24,25][23][24].8. Public Attitudes and Climate Policies

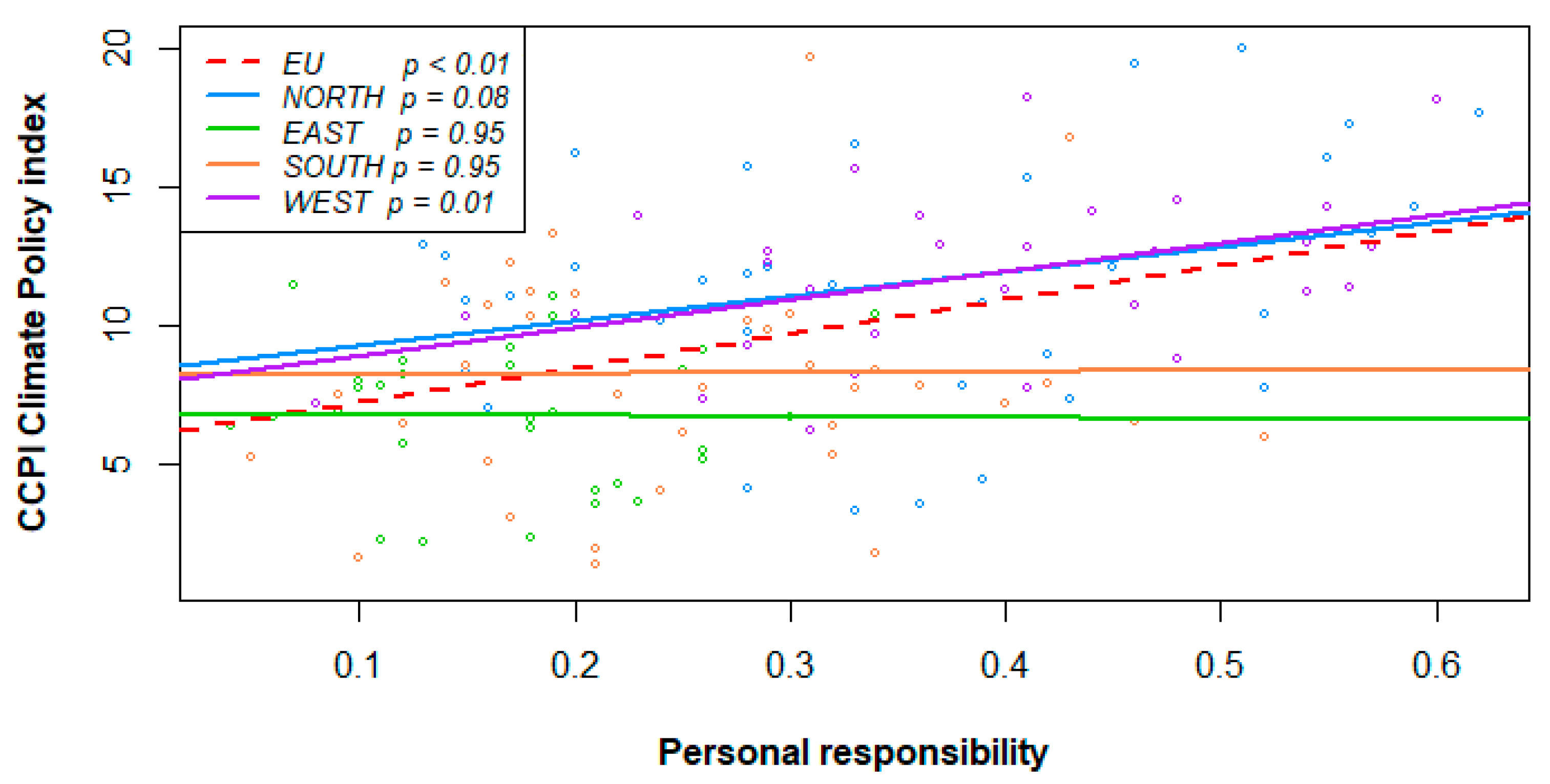

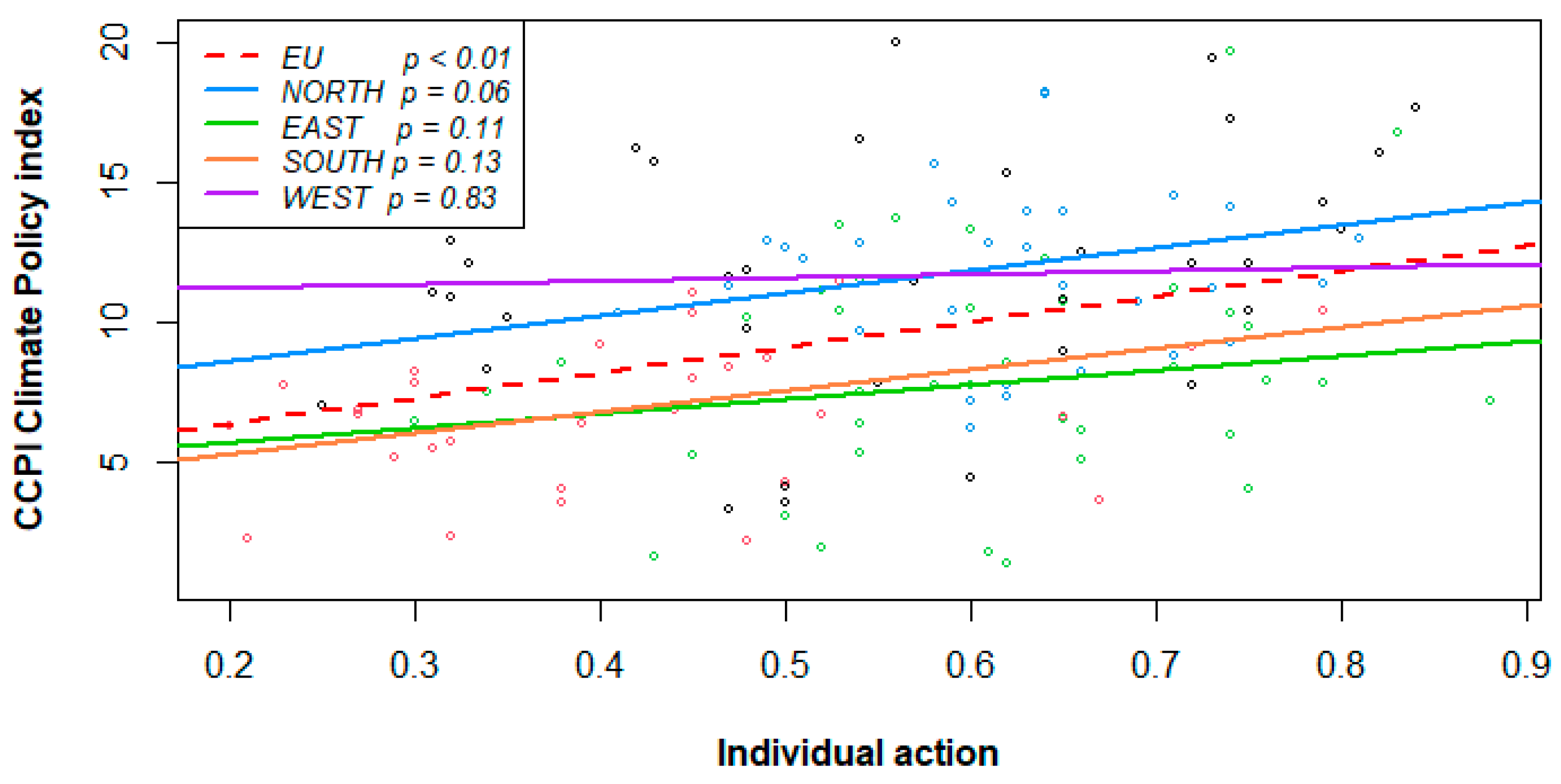

Combining domains again, wresearchers looked at a possible relationship between the three components of public attitudes towards climate change and climate policies at the EU- and macro-regional levels. According to ourthe results, the perceived seriousness of climate change and climate policy are not significantly related to one another, both at the EU and macro-regional levels. In contrast, in terms of perceived personal responsibility for tackling climate change, at the EU level, the relationship with climate policy is positive and significant (p < 0.01, F = 29.30, df = 132). At the macro-regional level, only the western countries (p = 0.01, F = 6.82, df = 28) show a significant positive relationship between personal responsibility for climate change and climate policy. In the other regions, there is no significant relationship between these variables. In terms of individual action to fight climate change, at the EU level, there is a positive and significant relationship with climate policy (p < 0.01, F = 18.15, df = 132). At the macro-regional level, no significant relationship was detected between individual action to fight climate change and climate policy. Figure 1 and Figure 2 show the linear regressions between climate policy (CCPI) and the Eurobarometer questions related to feelings of personal responsibility for climate change and individual action to fight climate change.

Figure 1. There is a positive relationship between the feeling of personal responsibility for climate change and climate policy at an EU level. Significant (0.05 > p ≥ 0.01), highly significant (p < 0.01).

Figure 2. There is a positive relationship between individual action to fight climate change and climate policy at an EU level. Significant (0.05 > p ≥ 0.01), highly significant (p < 0.01).

References

- Statista. Emissions in the EU—Statistics & Facts|Statista. 15 August 2022. Available online: https://www.statista.com/topics/4958/emissions-in-the-european-union/#dossierKeyfigures (accessed on 15 April 2023).

- Poortinga, W.; Whitmarsh, L.; Steg, L.; Böhm, G.; Fisher, S. Climate change perceptions and their individual-level determinants: A cross-European analysis. Glob. Environ. Change 2019, 55, 25–35.

- Oberthür, S.; Groen, L. The European Union and the Paris Agreement: Leader, mediator, or bystander? Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 2017, 8, e445.

- Nongqayi, L.; Risenga, I.; Dukhan, S. Youth’s knowledge and awareness of human contribution to climate change: The influence of social and cultural contexts within a developing country. Educ. Dev. Psychol. 2022, 3, 44–57.

- Cowls, J.; Tsamados, A.; Taddeo, M.; Floridi, L. The AI gambit: Leveraging artificial intelligence to combat climate change—Opportunities, challenges, and recommendations. AI Soc. 2023, 38, 283–307.

- Climate Action Tracker. Climate target updates slow as science ramps up need for action. In Climate Action Tracker Global Update September. 2021. Available online: https://climateactiontracker.org/documents/871/CAT_2021-09_Briefing_GlobalUpdate.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2023).

- Constantino, S.M.; Sparkman, G.; Kraft-Todd, G.T.; Bicchieri, C.; Centola, D.; Shell-Duncan, B.; Vogt, S.; Weber, E.U. Scaling Up Change: A Critical Review and Practical Guide to Harnessing Social Norms for Climate Action. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 2022, 23, 50–97.

- World Meteorological Organization. The State of the Global Climate 2021|World Meteorological Organization. 2021. Available online: https://public.wmo.int/en/our-mandate/climate/wmo-statement-state-of-global-climate (accessed on 15 April 2023).

- Jungmann, M.; Vardag, S.N.; Kutzner, F.; Keppler, F.; Schmidt, M.; Aeschbach, N.; Gerhard, U.; Zipf, A.; Lautenbach, S.; Siegmund, A.; et al. Zooming-in for climate action—Hyperlocal greenhouse gas data for mitigation action? Clim. Action 2022, 1, 1–8.

- Ponthieu, E. The European Green Deal and Other Climate Plans. In The Climate Crisis, Democracy and Governance; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 17–36.

- IPCC. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Masson-Delmotte, B.Z., Zhai, P., Pirani, A., Connors, S.L., Péan, C., Berger, S., Caud, N., Chen, Y., Goldfarb, L., Gomis, M.I., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021; Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/assessment-report/ar6/ (accessed on 15 April 2023).

- IPCC. Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. In Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Pörtner, H.-O., Roberts, D.C., Tignor, M., Poloczanska, E.S., Mintenbeck, K., Alegría, A., Craig, M., Langsdorf, S., Löschke, S., Möller, V., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022.

- Lamb, W.; Grubb, M.; Diluiso, F.; Minx, J. Countries with sustained greenhouse gas emissions reductions: An analysis of trends and progress by sector. Clim. Policy 2022, 22, 1–17.

- European Parliament. EU Progress towards 2020 Climate Change Goals (Infographic)|News|European Parliament. 2022. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/headlines/society/20180706STO07407/eu-progress-towards-2020-climate-change-goals-infographic (accessed on 15 April 2023).

- Davidovic, D.; Harring, N. Exploring the cross-national variation in public support for climate policies in Europe: The role of quality of government and trust. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2020, 70, 101785.

- Deutch, J. Is Net Zero Carbon 2050 Possible? Joule 2020, 4, 2237–2240.

- Poschmann, J.; Bach, V.; Finkbeiner, M. Are the EU climate ambitions reflected on member-state level for greenhouse gas reductions and renewable energy consumption shares? Energy Strategy Rev. 2022, 43, 100936.

- Ricart, S.; Olcina, J.; Rico, A.M. Evaluating Public Attitudes and Farmers’ Beliefs towards Climate Change Adaptation: Awareness, Perception, and Populism at European Level. Land 2018, 8, 4.

- Jakučionytė-Skodienė, M.; Liobikienė, G. The Changes in Climate Change Concern, Responsibility Assumption and Impact on Climate-friendly Behaviour in EU from the Paris Agreement Until 2019. Environ. Manag. 2022, 69, 1–16.

- Poortinga, W.; Fisher, S.; Bohm, G.; Steg, L.; Whitmarsh, L. European Attitudes to Climate Change and Energy. Topline Results from Round 8 of the European Social Survey; European Social Survey ERIC: London, UK, 2018.

- Arıkan, G.; Günay, D. Public attitudes towards climate change: A cross-country analysis. Br. J. Politics Int. Relat. 2021, 23, 158–174.

- Aguiar, F.C.; Bentz, J.; Silva, J.M.N.; Fonseca, A.L.; Swart, R.; Santos, F.D.; Penha-Lopes, G. Adaptation to climate change at local level in Europe: An overview. Environ. Sci. Policy 2018, 86, 38–63.

- Otto-Banaszak, I.; Matczak, P.; Wesseler, J.; Wechsung, F. Different perceptions of adaptation to climate change: A mental model approach applied to the evidence from expert interviews. Reg. Environ. Change 2011, 11, 217–228.

- Kundzewicz, Z.W.; Matczak, P.; Otto, I.M.; Otto, P.E. From “atmosfear” to climate action. Environ. Sci. Policy 2020, 105, 75–83.

More