This paper provides a detailed review of the application of hydrogel coatings in biomedical antibacterial applications and introduces the principles of adhesion on the surface of materials and antibacterial strategies. Hydrogels can be attached to the surface of biomaterials in three ways: The first is surface-initiated graft crosslinking polymerization. The second is anchoring the hydrogel coating to the substrate surface. The third is the LbL self-assembly technique to coat crosslinked hydrogels. Hydrogel coatings’ antibacterial strategies are divided into three types: The first type is bacteria repellence and inhibition. The second type is the contact surface killing of bacteria. The third type is the release of antibacterial agents.

The antibacterial hydrogel coating interacts with organic and inorganic components as a biocompatible surface modifier, and the coating acts as a buffer between biomaterials and human tissues, making the biphasic interface of the material more stable and flexible and meeting the various needs of human tissue repair. The two key advantages of hydrogel coatings are as follows: Firstly, the coating can be firmly attached to the surface through chemical crosslinking and various anchoring reactions. Secondly, the coatings can attach to almost all kinds of materials, such as precious metals, oxides, polymers, and ceramics. Hydrogel coatings have excellent prospects for application, simple processing, stable performance, and wide application. Although significant progress has resulted from the research of antibacterial hydrogel coatings in biomedical applications, most of the research is only at the stage of cell and animal experiments, and further research on subsequent clinical applications needs to be conducted. The current research difficulties include the following: Firstly, the preparation method of antibacterial hydrogel coatings needs to be improved. Although the graft density of surface-initiated graft crosslinking polymerization is high, the initiator needs to be grafted to the surface, and the preparation process is relatively complex. The method of fixing the hydrogel coating to the substrate surface may result in uneven coverage of the hydrogel coating to the substrate surface due to the steric hinderance of the graft chain. Secondly, greater attention should be given to the study of the chemical stability of hydrogel coatings, including swelling, durability, degradability, mechanical properties, etc., which are important for the long-term effect of antibacterial hydrogel coatings on the human body. For example, swelling could be a problem for the coating of tubular medical devices, as the large swelling degree of hydrophilic hydrogels might block the tube. Finally, sterilization has been reported as an issue for most hydrogel coatings. In the complex environment of the body, the hydrogel coating needs to adapt to high temperature, high pressure, oxidation, and other conditions but also needs to maintain adhesion properties and bactericidal activity on the surface of the substrate. These problems will become the focus of future research on antibacterial hydrogel coatings. Future research directions may focus on the following aspects. First, there is a need to improve the adhesion of hydrogel coatings. The graft density should be large and uniform, so that the hydrogel coating uniformly covers the surface of the substrate, which is convenient for subsequent modification. Second, improvement of the mechanical properties of hydrogels and study of their long-term chemical stability are required, including improving the mechanical properties and breaking strength of hydrogels by crosslinking other chemicals. A third focus is the improvement of the swelling property of hydrogel, which is controlled by the change of pH and temperature. Improvement of this property is necessary for an intelligent and stable hydrogel coating. Fourth is the selection of materials that use monomers or segments with controllable degradation cycles and that have nontoxicity and harmless degradation products. This review provides a theoretical reference for follow-up research.

The antibacterial hydrogel coating interacts with organic and inorganic components as a biocompatible surface modifier, and the coating acts as a buffer between biomaterials and human tissues, making the biphasic interface of the material more stable and flexible and meeting the various needs of human tissue repair. The two key advantages of hydrogel coatings are as follows: Firstly, the coating can be firmly attached to the surface through chemical crosslinking and various anchoring reactions. Secondly, the coatings can attach to almost all kinds of materials, such as precious metals, oxides, polymers, and ceramics. Hydrogel coatings have excellent prospects for application, simple processing, stable performance, and wide application. The current research difficulties include the following: Firstly, the preparation method of antibacterial hydrogel coatings needs to be improved. Although the graft density of surface-initiated graft crosslinking polymerization is high, the initiator needs to be grafted to the surface, and the preparation process is relatively complex. The method of fixing the hydrogel coating to the substrate surface may result in uneven coverage of the hydrogel coating to the substrate surface due to the steric hinderance of the graft chain. Secondly, greater attention should be given to the study of the chemical stability of hydrogel coatings, including swelling, durability, degradability, mechanical properties, etc., which are important for the long-term effect of antibacterial hydrogel coatings on the human body. For example, swelling could be a problem for the coating of tubular medical devices, as the large swelling degree of hydrophilic hydrogels might block the tube. Finally, sterilization has been reported as an issue for most hydrogel coatings. In the complex environment of the body, the hydrogel coating needs to adapt to high temperature, high pressure, oxidation, and other conditions but also needs to maintain adhesion properties and bactericidal activity on the surface of the substrate. These problems will become the focus of future research on antibacterial hydrogel coatings. Future research directions may focus on the following aspects. First, there is a need to improve the adhesion of hydrogel coatings. The graft density should be large and uniform, so that the hydrogel coating uniformly covers the surface of the substrate, which is convenient for subsequent modification. Second, improvement of the mechanical properties of hydrogels and study of their long-term chemical stability are required, including improving the mechanical properties and breaking strength of hydrogels by crosslinking other chemicals. A third focus is the improvement of the swelling property of hydrogel, which is controlled by the change of pH and temperature. Improvement of this property is necessary for an intelligent and stable hydrogel coating. Fourth is the selection of materials that use monomers or segments with controllable degradation cycles and that have nontoxicity and harmless degradation products.

- hydrogel coatings

- antibacterial property

- biomaterials

Hydrogels exhibit excellent moldability, biodegradability, biocompatibility, and extracellular matrix-like properties, which make them widely used in biomedical fields. Because of their unique three-dimensional crosslinked hydrophilic networks, hydrogels can encapsulate various materials, such as small molecules, polymers, and particles; this has become a hot research topic in the antibacterial field. The surface modification of biomaterials by using antibacterial hydrogels as coatings contributes to the biomaterial activity and offers wide prospects for development. A variety of surface chemical strategies have been developed to bind hydrogels to the substrate surface stably. We first introduce the preparation method for antibacterial coatings in this review, which includes surface-initiated graft crosslinking polymerization, anchoring the hydrogel coating to the substrate surface, and the LbL self-assembly technique to coat crosslinked hydrogels. Then, we summarize the applications of hydrogel coating in the biomedical antibacterial field. Hydrogel itself has certain antibacterial properties, but the antibacterial effect is not sufficient. In recent research, in order to optimize its antibacterial performance, the following three antibacterial strategies are mainly adopted: bacterial repellent and inhibition, contact surface killing of bacteria, and release of antibacterial agents. We systematically introduce the antibacterial mechanism of each strategy. The review aims to provide reference for the further development and application of hydrogel coatings.

1. Introduction

In the current biomedical field, medical devices, such as catheters, hernia nets, implants, and wound dressings, are often adhered by bacteria, leading to varying degrees of infection and posing a threat to the health of patients. Once bacteria adhere to the surface of the substrate, they will rapidly form a biofilm, which attracts more bacteria, affecting the antibacterial effect of the immune system. Therefore, the prevention of bacterial infection in the process of biomaterial implantation has become the focus of researchers. Surface coating or modification, which preserves the original properties of the material and changes only the surface properties, has been recognized as a promising strategy for introducing antibacterial efficacy into biomaterials. Some bionic surface morphologies with high aspect ratios are effective against colonization by bacteria, although the mechanism of antibacterial activity is not clear. For methods of tailoring surface chemistry, substrates can be chemically modified or physically coated with a variety of antibacterial substances, including polymers, functional groups, inorganic nanoparticles, hydrogels, and antibiotics. Among these bactericidal materials, hydrogel coating has many advantages and has been widely studied.

2. Preparation Methods of Hydrogel Coatings

Hydrogels are prepared by chemical and physical crosslinking, but it is challenging to fix physically crosslinked hydrogels on the surface of materials due to the lack of binding sites for binding into the three-dimensional network. In addition, the poor mechanical properties of physically crosslinked hydrogels compared to chemically crosslinked hydrogels limit the application of physically crosslinked hydrogels as durable coating materials [38]. The chemically crosslinked hydrogels can be gelatinized by monomer polymerization or conjugation reactions between polymer chains, whereby we can attach these hydrogels to the material surface in various ways to form stable hydrogel coatings. The general strategies can be divided into three types: The first is surface-initiated graft crosslinking polymerization. The second is anchoring the hydrogel coating to the substrate surface. Third is the LbL self-assembly technique to coat crosslinked hydrogels.

2.1. Surface-Initiated Graft Crosslinking Polymerization

Free radical polymerization is a crucial way to prepare polymeric materials. The polymerization reaction is initiated by active radicals located on the surface of the substrate, so the adhesion of hydrogels can be promoted by generating active radicals on the substrate surface and introducing grafting sites on the surface.

2.1.1. Direct Generation of Reactive Radicals on the Substrate Surface

2.1.2. Introduction of Peroxide Groups on the Substrate Surface

2.1.3. Introduction of Catechol Groups on the Substrate Surface

2.1.4. Introduction of Silane Coupling Agents on the Substrate Surface

2.2. Anchoring the Hydrogel Coating to the Substrate Surface

The preparation of stable polymer brushes on the material surface is possible by initiating graft-crosslinking polymerization on the substrate surface, which introduces a high density of reaction sites. However, the reaction efficiency is low, and the preparation of hydrogel coatings on the material surface does not require too many reaction sites. In general terms, the hydrogel can be thought of as a large molecule; immobilization on the material surface improves the coating binding stability and reaction efficiency.

2.2.1. Click Chemistry for Anchoring Hydrogels to the Substrate Surface

2.2.2. Dopamine Group Functionalized Hydrogels Anchored on the Substrate Surface

2.2.3. Anchoring Hydrogel Layers by Free Radical Polymerization

2.3. LbL Self-Assembly Technique to Coat Crosslinked Hydrogels

The layer-by-layer self-assembly technique may prepare coatings on substrate surfaces through alternating deposition methods, and the coatings can be attached mainly by hydrogen bonding, electrostatic interactions, and charge transfer interactions. Because of the low stability of such noncovalent bonding forces, each layer can be deposited conjugately by covalent bonding in the preparation of hydrogel coatings. The LbL self-assembly technique is more suitable for preparing ultrathin hydrogel coatings. The substrate surface needs pretreatment, and the covalent attachment of the layer to the substrate surface may be realized by grafting functional groups. For example, the surface of the silicon wafer undergoes functionalization through reactants containing dopamine groups; an ultrathin hydrogel coating can be prepared by depositing alternating polyacrylic acid (PAA) and chitosan quaternary ammonium salts using the LbL self-assembly technique. The coating surface is positively charged and effectively inhibits bacterial adhesion.

3. Hydrogel Coatings in Biomedical Antibacterial Applications

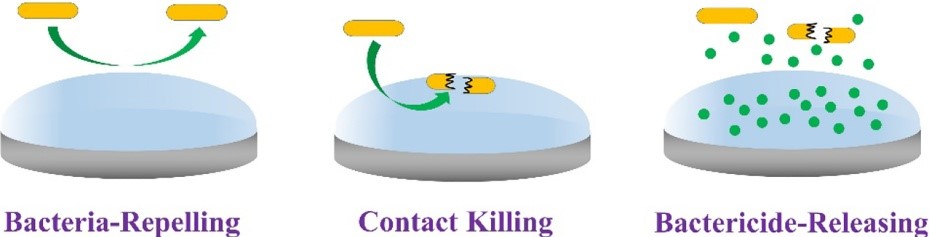

The following three antibacterial methods are the main methods for material surface modification by hydrogel coatings: The first is bacterial repellence and inhibition. The second is the contact surface killing of bacteria. The third is the release of antibacterial agents (Figure 7).

3.1. Bacterial Repellence and Inhibition

In the earliest stage of bacterial biofilm formation, bacterial adhesion on the surface is reversible, so the introduction of hydrogel coatings that repell bacterial adhesion is the most direct antibacterial method. The hydrogel coating prepared by this method has better biocompatibility. When biomaterials are implanted into the body, proteins tend to absorb nonspecifically on the surface, which promotes bacterial adhesion; thus, the repellent hydrogel coating should effectively inhibit the nonspecific absorption of proteins. Substances with hydrogen bonding acceptors and hydrophilic polar functional groups may inhibit the nonspecific absorption of proteins; they may form hydrogen bonds with water molecules in aqueous media and form a highly hydrated layer on the polymer surface to effectively achieve antibacterial properties. Polyethylene glycols (PEG), polyvinyl alcohols (PVA), polyacrylates, amphiphilic polymers, polysaccharides, and other hydrophilic substances are widely used as raw materials in the field of antibacterial hydrogels [80]. Next, the applications of hydrogel coatings containing the above substances in biomaterials are introduced.

3.2. Contact Surface Killing of Bacteria

Researches show that the combination of bactericidal compounds and hydrogel coatings can effectively kill bacteria. Different from the passive antibacterial mechanism of bacterial-repelling hydrogel coatings, the bactericidal hydrogel coating can actively kill bacteria by destroying the cell membrane of bacteria, thus preventing the propagation of bacteria and achieving effective antibacterial activity. The bactericidal compounds commonly used generally contain cations and hydrophobic groups, and since bacteria have negative charges, they can be adsorbed by the cations of the bactericidal compounds. The hydrophobic groups of bactericides may also damage the lipid composition of the bacterial membranes. Some widely used bactericides are antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) and quaternary ammonium compounds (QACs).

3.3. Release of Antibacterial Agents

The three-dimensional network structure of hydrogels can be loaded with antibiotics, AMPs, cationic polymers, silver ions, copper ions, antibacterial drugs, and other bactericidal compounds to enhance the antibacterial properties of the biomaterials. Compared with the above two methods, this method is more flexible and controllable, repelling bacteria and killing bacteria via released antibacterial agents. However, the preparation process is relatively complex and requires consideration of the release rate and concentration of the antimicrobial agents. For example, Hoque et al. prepared a biocompatible hydrogel using dextran methacrylate (Dex-MA) as a monomer and encapsulated it with a small molecular cationic biocide by in situ loading during photopolymerization. The hydrogels showed a sustained release of biocide and displayed 100% activity against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) for an extended period of time (until day 5).

Due to the limitation of the surface hydrogel coating function, the coated antibacterial substance will become depleted gradually and cannot maintain an excellent antibacterial effect for a long period. Therefore, the release rate of antibacterial substances should be reasonably controlled. Thus, an intelligently controlled release coating structure can be prepared to release antibacterial substances under specific conditions (pH, light reaction, temperature, and REDOX reaction) to kill bacteria and free bacteria attached to the material surface. The applications of these intelligent controlled-release hydrogel coatings will be described in the following sections.