Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Piotr Rzeźniczek | -- | 2082 | 2023-10-13 11:56:30 | | | |

| 2 | Rita Xu | -2 word(s) | 2080 | 2023-10-13 12:03:05 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Rzeźniczek, P.; Gaczkowska, A.D.; Kluzik, A.; Cybulski, M.; Bartkowska-Śniatkowska, A.; Grześkowiak, M. Lazarus Phenomenon. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/50263 (accessed on 08 February 2026).

Rzeźniczek P, Gaczkowska AD, Kluzik A, Cybulski M, Bartkowska-Śniatkowska A, Grześkowiak M. Lazarus Phenomenon. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/50263. Accessed February 08, 2026.

Rzeźniczek, Piotr, Agnieszka Danuta Gaczkowska, Anna Kluzik, Marcin Cybulski, Alicja Bartkowska-Śniatkowska, Małgorzata Grześkowiak. "Lazarus Phenomenon" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/50263 (accessed February 08, 2026).

Rzeźniczek, P., Gaczkowska, A.D., Kluzik, A., Cybulski, M., Bartkowska-Śniatkowska, A., & Grześkowiak, M. (2023, October 13). Lazarus Phenomenon. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/50263

Rzeźniczek, Piotr, et al. "Lazarus Phenomenon." Encyclopedia. Web. 13 October, 2023.

Copy Citation

Autoresuscitation is a phenomenon of the heart during which it can resume its spontaneous activity and generate circulation. It was described for the first time by K. Linko in 1982 as a recovery after discontinued cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). J.G. Bray named the recovery from death the Lazarus phenomenon in 1993. It is based on a biblical story of Jesus’ resurrection of Lazarus four days after confirmation of his death. Up to the end of 2022, 76 cases (coming from 27 countries) of spontaneous recovery after death were reported; among them, 10 occurred in children. The youngest patient was 9 months old, and the oldest was 97 years old. The longest resuscitation lasted 90 min, but the shortest was 6 min.

Lazarus phenomenon

Lazarus syndrom

autoresuscitation

1. The Death and Resurrection of Lazarus

Now a certain man was sick, Lazarus of Bethany, the village of Mary and her sister Martha. It was the Mary who anointed the Lord with ointment, and wiped His feet with her hair, whose brother Lazarus was sick. So the sisters sent word to Him, saying, “Lord, behold, he whom You love is sick”. But when Jesus heard this, He said, “This sickness is not to end in death, but for the glory of God…”. Now Jesus had spoken of his death, but they thought that He was speaking of literal sleep. So Jesus then said to them plainly, “Lazarus is dead, and I am glad for your sakes that I was not there, so that you may believe; but let us go to him”. So when Jesus came, He found that he had already been in the tomb four days. So Jesus, again being deeply moved within, came to the tomb. Now it was a cave, and a stone was lying against it. Jesus said, “Remove the stone”. Martha, the sister of the deceased, said to Him, “Lord, by this time there will be a stench, for he has been dead four days”. Jesus said to her, “Did I not say to you that if you believe, you will see the glory of God?”. So they removed the stone. Then Jesus raised His eyes, and said, “Father, I thank You that You have heard Me. “Lazarus, come forth”. The man who had died came forth, bound hand and foot with wrappings, and his face was wrapped around with a cloth. Jesus said to them, “Unbind him, and let him go”. John 11: New American Standard Bible 1995 (NASB95) [1].

2. Introduction

The phenomenon of Lazarus syndrome presented in this article, otherwise known as autoresuscitation, is a phenomenon known in the literature, although no sufficient scientific evidence pointing to the specific cause of such phenomenon has been demonstrated so far. The intention of the authors is to present to the medical community a problem connected to the spontaneous return of life functions after the patient’s death.

Throughout centuries there has always been a fear among people that one may wake up in the coffin after being buried. That concern stemmed from the difficulty of confirming death.

There are known cases in the literature describing patients who, after being pronounced dead, somehow became alive again. This phenomenon resulted in the past from a lack of possibility to exclude the so-called reversible causes of cardiac arrest, among others, such as hypothermia or poisoning included in the updated guidelines of the European Resuscitation Council (ERC) 2021 [2]. In the past special coffins were even constructed, which enabled the communication of the buried deceased people with those alive should the signs of life return to them.

Nowadays, the declaration of death is not as difficult as before. Currently, the technical improvements enable us to perform thorough diagnostics, which limit the possibility of an “error” and of coming back to life of a patient who had been pronounced dead.

3. Lazarus Phenomenon—What Do We Know?

The cases of patients in which life functions, including heart rate, have been restored after death have been presented in world literature. Initially, this phenomenon became known as “autoresuscitation” and was described for the first time in 1982 by K. Linko et al. [3]. The definition of this phenomenon as “Lazarus Syndrome/Phenomenon” was proposed by J.G Bray in 1993, influenced by the Bible story about Lazarus, who was resurrected by Jezus 4 days after his death [4]. In his 2004 article, E.F. Wijdicks specified that autoresuscitation is a phenomenon of the heart, which can resume spontaneous activity and thus generate a heartbeat [5]. It has been noted that “autoresuscitation” or “coming back to life” can occur following insufficient resuscitation or lack thereof when the circulation is restored by itself (spontaneously).

The data from the literature point to various times of returning of the life functions, from a few seconds to several dozen minutes. A case of autoresuscitation after 30 s was reported by JP Duff [6]; however, the longest recorded time of resuming all life function presented in literature so far—180 min—has been described by AT Guyen [7]. The greatest number of autoresuscitation cases described as Lazarus Syndrome took place within a few minutes time frame and this is why most authors recommend at least 10 min monitoring of the patient’s ECG recording following the cessation of all resuscitation procedures in order to exclude autoresuscitation.

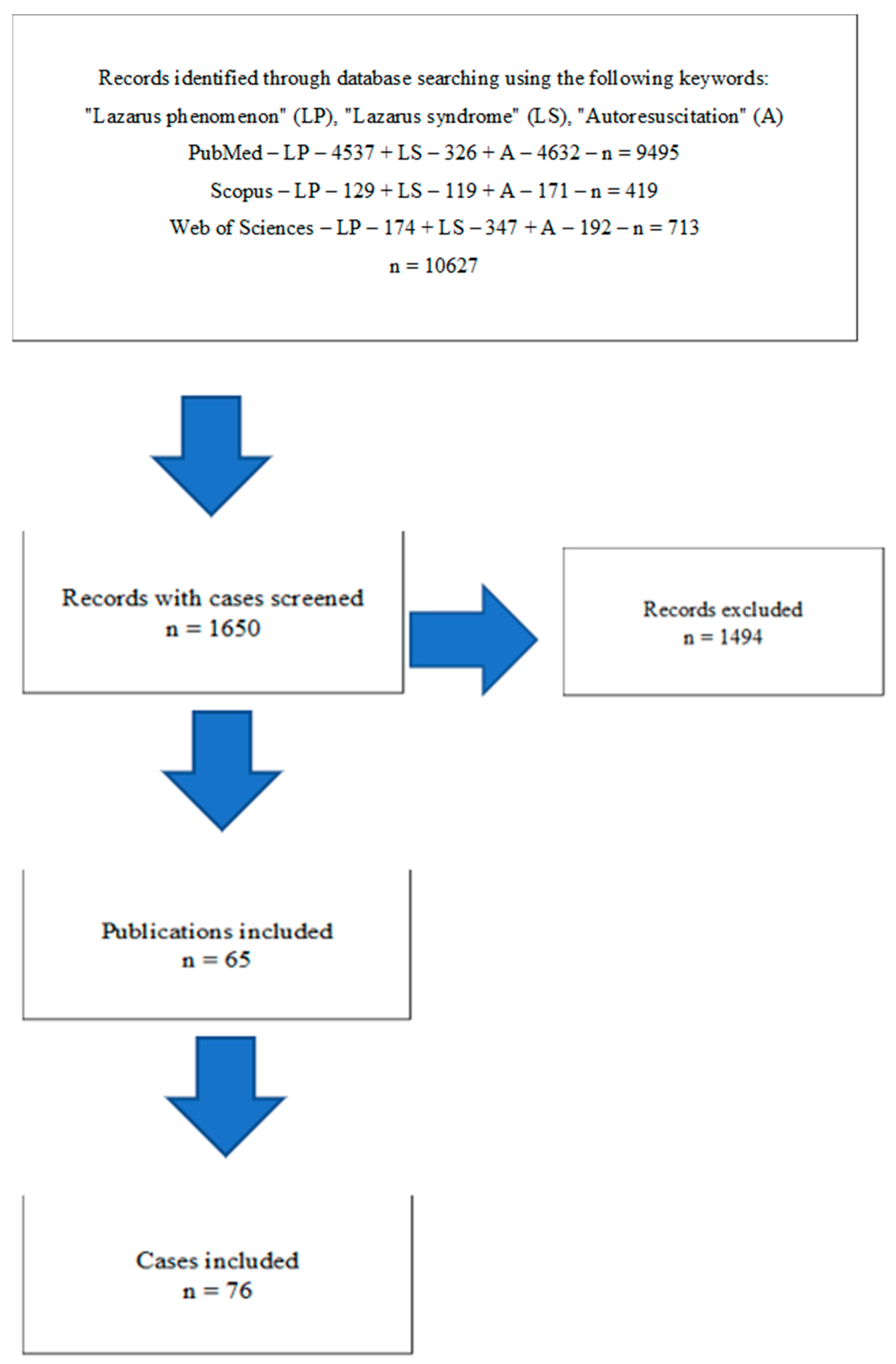

The following three electronic databases were searched, containing all reports published from the year 1982 until 31 December 2022: PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science. The phrases used for analyses were: “Lazarus phenomenon” or “Lazarus or phenomenon”, “Lazarus syndrome or Lazarus or syndrome”, and “Autoresuscitation or Auto-resuscitation”. Each database was independently reviewed by two members of the research team, and the results were compared. Duplicated records were excluded, as well as review articles. In the remaining original reports, researchers searched case reports of Lazarus syndrome. Finally, researchers found 10,627 records, 1650 entries met the criteria for inclusion in the initial analysis, and after further exclusion of 1494 reports, researchers received 65 publications in which 76 cases of Lazarus syndrome were described.

Figure 1 illustrates how the data was collected.

Figure 1. Flowchart of case selection.

4. Presumed Causes of Lazarus Syndrome

At this point, it is not known precisely what factors lead to autoresuscitation. Based on available publications, the factors that can be taken into account include hyperventilation, alkalosis, auto-PEEP (positive end-expiratory pressure), delayed drug action, hyperkalemia, unnoticeable vital signs as well as metabolic disorders [8][9].

Hyperventilation means the state of over-ventilation of a patient resulting from the administration of too much of the tidal volume with excessive frequency. It leads to a decrease in partial pressure of carbon dioxide (pCO2) and further to the development of respiratory alkalosis. It results in a shift in the hemoglobin dissociation curve to the left and reduced oxygen delivery to the tissues. The consequence of hyperventilation is cerebral vasoconstriction, which can lead to hypoxia of the central nervous system. It seems that the most important mechanism in Lazarus syndrome, which should be considered during hyperventilation, is a shortening of the exhalation time, leading to increased intrathoracic pressure and decreased venous return with a subsequent decrease in cardiac output. Decreased venous return translates directly to a slower delivery of drugs to the central circulation (and thus to delayed drug action, which is cited as another mechanism). When death is confirmed, resuscitation is discontinued, and then the patient’s “overventilation” state may be reversed. Generated due to excessive hyperventilation, the pressure in the chest is lowered, and perhaps by this mechanism, the heart can restart its activity. Cases of hyperventilation as a mechanism underlying Lazarus syndrome have been reported in children [6].

Auto-PEEP (Positive End Expiratory Pressure) [10], i.e., positive end-expiratory pressure in the airway, a type of air trap, which is predisposed by factors such as shortening the expiration time by increasing the respiratory rate, tidal volume, or inspiratory time, which is characteristic of hyperventilation and, similarly to hyperventilation, may lead to an increase in intrathoracic pressure, which may result in impaired venous return to the heart and a decrease in its output [11][12]. In this case, venous return is also reduced and may also slow down the distribution of drugs to the central circulation, referred to as the delayed-action mechanism. The confirmation of the above causes—i.e., hyperventilation and auto-PEEP—may be the case of the so-called incomplete Lazarus syndrome in a 7-day-old newborn admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit after aortic coarctation surgery [11]. Eight hours after surgery, the newborn in the ward had a significant drop in blood pressure (MAP 20–25 mmHg), with a heart rate of 70–80/min. Ventilation with a self-inflating bag was introduced, but the hypotension deepened, and only after the cessation of mechanical ventilation did the arterial pressure begin to increase. Suspecting the negative impact of excessive ventilation on the circulatory system, the number of breaths from the ventilator and PEEP were reduced, and within a few seconds, the return of a well-palpable pulse and normal sinus rhythm was observed. Cessation of mechanical ventilation and subsequent decrease in respiratory parameters led to the normalization of arterial pressure. This confirms one of the presumed causes of autoresuscitation—that is, hyperventilation, dynamic hyperinflation of the lungs together with air trapping (which in the described newborn was also confirmed in a chest radiograph). The following are also cited as the causes of the Lazarus phenomenon: lack of observation of vital signs (in the case of, for example, hypothermia), poisoning, and hyperkalemia. However, they are all listed in the European Resuscitation Guidelines (ERC 2021) as reversible causes of cardiac arrest that should be considered during resuscitation. If confirmed, the patient must be treated appropriately and cannot be pronounced dead.

Based on current data from the literature, researchers have described above the most likely causes of Lazarus syndrome, which have not been proven so far. Researchers included the others as “controversial” because they are part of the reversible causes of cardiac arrest (which, according to the ERC 2021 guidelines starting from letter “H”, are: hypoxia, hypo-/hyperthermia, hypovolemia, hypo-/hyperkalemia, and metabolic disturbances [2]) and cannot be considered as separate causes.

Based on the available literature on the subject, some of the “controversial” causes of the Lazarus phenomenon will be discussed below.

A patient who shows no minimal vital signs, where a probable cause may be even hypothermia [13], presents with a controversial situation because hypothermia is a reversible cause of cardiac arrest, and only its exclusion or an increase in the patient’s body temperature may justify the declaration of death. Nevertheless, there are scientific reports which describe it as one of the reasons for the Lazarus phenomenon. In the case of hypothermia, biochemical processes are slowed down, which translates into the slowdown of basic life functions—virtually imperceptible breathing and pulse. Hypothermia is a state of decreased core body temperature with the distinction of several stages: mild, moderate, and severe hypothermia. In severe hypothermia (below 28 °C), all life processes slow down significantly with bradycardia, dilated pupils, lack of pupil reaction to light, and cardiac arrhythmias leading to cardiac arrest [14]. The above symptoms of hypothermia (especially in the deep stage) are identical to the clinical symptoms occurring in clinical death. Clinical death is a reversible condition. Resuscitation procedures in hypothermia, their length, drug distribution, etc., differ significantly from standard procedures [2]. In this case, it is important to consider the circumstances in which cardiac arrest occurred, the quality and conditions of resuscitation, the experience of medical personnel in recognizing minimal signs of life, proper patient monitoring, and consideration of advanced diagnostic techniques in making a decision to continue or withdraw from resuscitation.

Other causes of the Lazarus phenomenon are poisoning, i.e., a broadly understood phenomenon associated with the presence of harmful substances, poisons, drugs, etc., in the body. Toxic substances interact with compounds involved in physiological processes, disrupting their proper functioning at the systemic, cellular, or subcellular (mitochondrial) level. Diagnosis of poisoning is not always straightforward, and the supply of antidotes in such situations is often difficult and, in some situations, impossible [15]. Like hypothermia, poisoning is one of the reversible causes of cardiac arrest.

Hyperkalemia was mentioned in the cited literature as one of the causes of cardiac arrest in the course of renal failure and was also considered among the causes of the Lazarus phenomenon. Excessive levels of potassium ions lead to myocardial dysfunction in the sodium-potassium pump mechanism, which results in life-threatening arrhythmias, including cardiac arrest [16].

In the interpretation of the causes of autoresuscitation, the fact of the coexistence of many diseases in the patient is emphasized (e.g., cancer, cardiovascular diseases—e.g., cardiomyopathy [17], ischemic heart disease, sepsis [18]), as well as the patient’s advanced age [19]—the older the patient, the worse the prognosis, which undoubtedly affects survival after resuscitation.

References

- John 11. In New American Standard Bible; (NASB95); The Lockman Foundation: La Habra, CA, USA, 1995; Available online: https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=John%2011&version=NASB1995 (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- European Resuscitation Council. Guidelines for Resuscitation 2021; European Resuscitation Council: Brussels, Belgium, 2021; 161p.

- Linko, K.; Honkavaara, P.; Salmenpera, M. Recovery after discontinued cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Lancet 1982, 1, 106–107.

- Bray, J.G., Jr. The Lazarus phenomenon revisited. Anesthesiology 1993, 78, 991.

- Wijdicks, E.F.; Diringer, M.N. Electrocardiographic activity after terminal cardiac arrest in neurocatastrophes. Neurology 2004, 62, 673–674.

- Duff, J.P.; Joffe, A.R.; Sevcik, W.; deCaen, A. Autoresuscitation after pediatric Cardiac Arrest. Is hyperventilation a cause? Pediatr. Emerg. Care 2011, 27, 208–209.

- Guven, A.T.; Petridis, G.; Ozkal, S.S.; Kalfoglu, E.A. Lazarus Phenomenon in Medicolegal Prospective: A case report. Bull. Leg. Med. 2017, 22, 224–227.

- Rogers, P.L.; Schlichtig, R.; Miro, A.; Pinsky, M. Auto-PEEP during CPR. An “occult” cause of electromechanical dissociation? Chest 1991, 99, 492–493.

- Kämäräinen, A.; Virkkunen, I.; Holopainen, L.; Erkkilä, E.P.; Yli-Hankala, A.; Tenhunen, J. Spontaneous defibrillation after cessation of resuscitation in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: A case of Lazarus phenomenon. Resuscitation 2007, 75, 543–546.

- Laghi, F.; Goyal, A. Auto-PEEP in respiratory failure. Minerva Anestesiol. 2012, 78, 201–221.

- Gutierrez, S.G.S.; Montoro, V.D.; Gómez, J.M.G.; Manso, G.M. Dynamic hyperinflation, a case report. Pediatr. Int. 2020, 62, 647–649.

- Berlin, D. Hemodynamic consequences of auto-PEEP. J. Intensive Care Med. 2014, 29, 81–86.

- Peiris, A.N.; Jaroudi, S.; Gavin, M. Hypothermia. JAMA 2018, 319, 1290.

- Willmore, R. Cardiac Arrest Secondary to Accidental Hypothermia: Rewarming Strategies in the Field. Air Med. J. 2020, 39, 64–67.

- Habacha, S.; Mghaieth Zghal, F.; Boudiche, S.; Fathallah, I.; Blel, Y.; Aloui, H.; Mourali, M.S.; Brahmi, N.; Kouraichi, N. Toxin-induced cardiac arrest: Frequency, causative agents, management and hospital outcome. Tunis Med. 2020, 98, 123–130.

- Long, B.; Warix, J.R.; Koyfman, A. Controversies in Management of Hyperkalemia. J. Emerg. Med. 2018, 55, 192–205.

- Brieler, J.; Breeden, M.A.; Tucker, J. Cardiomyopathy: An Overview. Am. Fam. Physician 2017, 96, 640–646.

- Morgan, R.W.; Fitzgerald, J.C.; Weiss, S.L.; Nadkarni, V.M.; Sutton, R.M.; Berg, R.A. Sepsis-associated in-hospital cardiac arrest: Epidemiology, pathophysiology, and potential therapies. J. Crit. Care 2017, 40, 128–135.

- Hirlekar, G.; Karlsson, T.; Aune, S.; Ravn-Fischer, A.; Albertsson, P.; Herlitz, J.; Libungan, B. Survival and neurological outcome in the elderly after in-hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation 2017, 118, 101–106.

More

Information

Subjects:

Health Care Sciences & Services

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.7K

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

13 Oct 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No