| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Saoni Banerjee | -- | 1323 | 2023-09-15 15:16:15 | | | |

| 2 | Lindsay Dong | Meta information modification | 1323 | 2023-09-19 03:24:33 | | | | |

| 3 | Lindsay Dong | -31 word(s) | 1292 | 2023-09-19 10:49:13 | | |

Video Upload Options

Poverty increases vulnerability towards somatisation and influences the sense of mastery and well-being. The present study on adolescents living in relative poverty in a high-income group country (Israel) and a low-middle-income group country (India) explored the nature of somatisation tendency (ST) and its relationship with potency and perception of poverty (PP). Potency, a buffer against stress-induced negative health effects, was hypothesized to be negatively related to ST and mediate the link between PP and ST. Purposive sampling was used to collect questionnaire-based data from community youth (12–16 years) of two metropolitan cities—Kolkata (India, N = 200) and Tel-Aviv (Israel, N = 208). A clinically significant level of ST was reported by both Indian and Israeli youth experiencing 5–7 somatic symptoms on average. Potency was found to be a significant predictor of ST in both countries (p < 0.05) and emerged as a significant mediator (p < 0.001) in the PP and ST relationship among Indian adolescents.

1. Introduction

2. Somatisation and Poverty in Low-Income Adolescent Groups

2.1. Somatisation Tendency

2.2. Somatisation and Poverty in Adolescence

2.3. Somatisation and Potency in Adolescence

References

- Yates, W.R.; Dunayevich, E. Medscape—Somatic Symptom Disorders. 2014. Available online: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/294908-overview (accessed on 5 July 2017).

- Rhee, H.; Miles, M.S.; Halpern, C.T.; Holditch-Davis, D. Prevalence of recurrent physical symptoms in US adolescents. Pediatr. Nurs. 2005, 31, 314.

- Swain, M.S.; Henschke, N.; Kamper, S.J.; Gobina, I.; Ottová-Jordan, V.; Maher, C.G. An international survey of pain in adolescents. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 447.

- Viernes, N.; Zaidan, Z.A.; Dorvlo, A.S.; Kayano, M.; Yoishiuchi, K.; Kumano, H.; Kuboki, T.; Al-Adawi, S. Tendency toward deliberate food restriction, fear of fatness and somatic attribution in cross-cultural samples. Eat. Behav. 2007, 8, 407–417.

- Cheng, Q.; Xu, Y.; Xie, L.; Hu, Y.; Lv, Y. Prevalence and environmental impact factors of somatization tendencies in eastern Chinese adolescents: A multicenter observational study. Cad. Saude Publica 2019, 35, e00008418.

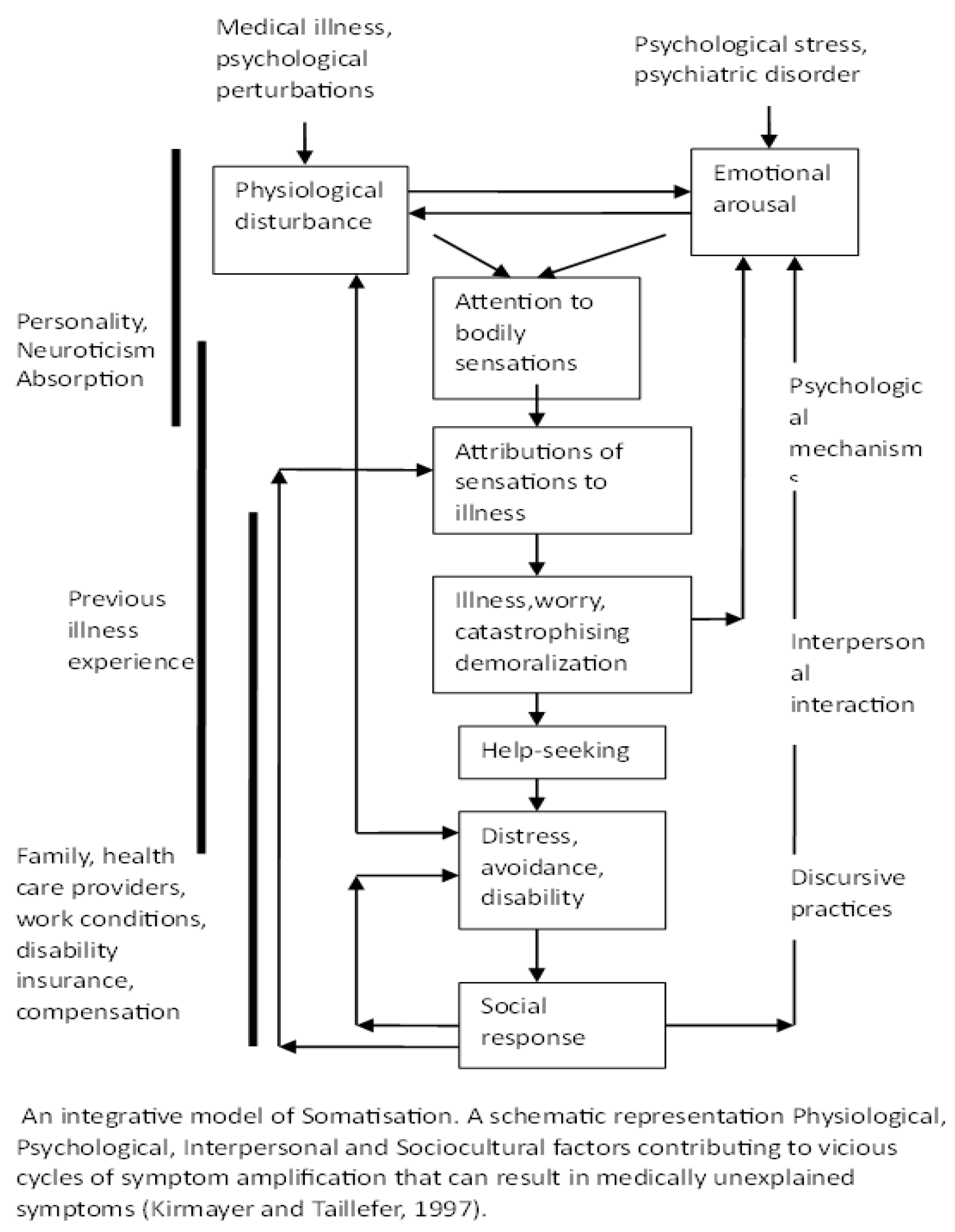

- Kirmayer, L.J.; Taillefer, S. Somatoform disorders. In Adult Psychopathology, 3rd ed.; Hersen, M., Turner, S., Eds.; John Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1997.

- Hobfoll, S.E. Social and psychological resources and adaptation. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2002, 6, 307–324.

- OECD. Education at a Glance 2014: OECD Indicators; OECD: Paris, France, 2018.

- Patel, N. Understanding Psychological Conflicts in Patients with Essential Hypertension and Exploring Matching Homoeopathic Remedies. Homœopath. Links 2018, 31, 234–240.

- Dimsdale, J.E.; Creed, F.; Escobar, J.; Sharpe, M.; Wulsin, L.; Barsky, A.; Lee, S.; Irwin, M.R.; Levenson, J. Somatic symptom disorder: An important change in DSM. J. Psychosom. Res. 2013, 75, 223–228.

- Dijkstra-Kersten, S.M.; Sitnikova, K.; van Marwijk, H.W.; Gerrits, M.M.; van der Wouden, J.C.; Penninx, B.W.; van der Horst, H.E.; Leone, S.S. Somatisation as a risk factor for incident depression and anxiety. J. Psychosom. Res. 2015, 79, 614–619.

- Creed, F.H.; Davies, I.; Jackson, J.; Littlewood, A.; Chew-Graham, C.; Tomenson, B.; Macfarlane, G.; Barsky, A.; Katon, W.; McBeth, J. The epidemiology of multiple somatic symptoms. J. Psychosom. Res. 2012, 72, 311–317.

- Lee, S.; Creed, F.H.; Ma, Y.L.; Leung, C.M. Somatic symptom burden and health anxiety in the population and their correlates. J. Psychosom. Res. 2015, 78, 71–76.

- Ruchkin, V.; Schwab-Stone, M. A longitudinal study of somatic complaints in urban adolescents: The role of internalizing psychopathology and somatic anxiety. J. Youth Adolesc. 2014, 43, 834–845.

- Bae, S.M.; Kang, J.M.; Chang, H.Y.; Han, W.; Lee, S.H. PTSD correlates with somatization in sexually abused children: Type of abuse moderates the effect of PTSD on somatization. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0199138.

- Raffagnato, A.; Angelico, C.; Valentini, P.; Miscioscia, M.; Gatta, M. Using the Body When There Are No Words for Feelings: Alexithymia and Somatization in Self-Harming Adolescents. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 262.

- Karkhanis, D.G.; Winsler, A. Somatization in children and adolescents: Practical implications. J. Indian Assoc. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2016, 12, 79–115.

- Frenkel, L.; Swartz, L.; Bantjes, J. Chronic traumatic stress and chronic pain in the majority world: Notes towards an integrative approach. Crit. Public Health 2018, 28, 12–21.

- Bourdillon, M.; Boyden, J. (Eds.) Growing Up in Poverty: Findings from Young Lives; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014.

- Brando, N.; Schweiger, G. (Eds.) Philosophy and Child Poverty: Reflections on the Ethics and Politics of Poor Children and Their Families; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; Volume 1.

- Marmot, M.; Allen, J.; Bell, R.; Bloomer, E.; Goldblatt, P. WHO European review of social determinants of health and the health divide. Lancet 2012, 380, 1011–1029.

- Kirmayer, L.J.; Young, A. Culture and somatization: Clinical, epidemiological, and ethnographic perspectives. Psychosom. Med. 1998, 60, 420–430.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013.

- Hughes, M.; Tucker, W. Poverty as an adverse childhood experience. North Carol. Med. J. 2018, 79, 124–126.

- Shonkoff, J.P.; Garner, A.S.; Siegel, B.S.; Dobbins, M.I.; Earls, M.F. Technical Report: The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. From The committees on psychosocial aspects of child and family health; early childhood, adoption and dependent care, and section on developmental and behavioral pediatrics. Pediatrics 2012, 129, e232–e246.

- Babu, A.R.; Aswathy Sreedevi, A.J.; Krishnapillai, V. Prevalence and determinants of somatization and anxiety among adult women in an urban population in Kerala. Indian J. Community Med. 2019, 44 (Suppl. S1), S66.

- Gureje, O.; Simon, G.E.; Ustun, T.B.; Goldberg, D.P. Somatization in cross-cultural perspective: A World Health Organization study in primary care. Am. J. Psychiatry 1997, 154, 989–995.

- Wagle, U.R. Poverty in Kathmandu: What do subjective and objective economic welfare concepts suggest? J. Econ. Inequal. 2006, 5, 73–95.

- Blackorby, C.; Donaldson, D. Welfare ratios and distributionally sensitive cost-benefit analysis. J. Public Econ. 1987, 34, 265–290.

- Rank, M.R.; Hirschl, T.A. The likelihood of experiencing relative poverty over the life course. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0133513.

- Lee, K.; Zhang, L. Cumulative Effects of Poverty on Children’s Social-Emotional Development: Absolute Poverty and Relative Poverty. Community Ment. Health J. 2022, 58, 930–943.

- Sen, A.K. Commodities and Capabilities; Elsevier Science Publishers: Oxford, UK, 1985.

- Sen, A.K. Development as Freedom; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1999.

- Cook, J.A.; Mueser, K.T. Is recovery possible outside the financial mainstream? Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2016, 39, 295–298.

- Sylvestre, J.; Notten, G.; Kerman, N.; Polillo, A.; Czechowki, K. Poverty and serious mental illness: Toward action on a seemingly intractable problem. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2018, 61, 153–165.

- Joychan, S.; Kazi, R.; Patel, D.R. Psychosomatic pain in children and adolescents. J. Pain Manag. 2016, 9, 155.

- Petanidou, D.; Giannakopoulos, G.; Tzavara, C.; Dimitrakaki, C.; Kolaitis, G.; Tountas, Y. Adolescents’ multiple, recurrent subjective health complaints: Investigating associations with emotional/behavioural difficulties in a cross-sectional, school-based study. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2014, 8, 1–8.

- Ran, L.; Wang, W.; Ai, M.; Kong, Y.; Chen, J.; Kuang, L. Psychological resilience, depression, anxiety, and somatization symptoms in response to COVID-19: A study of the general population in China at the peak of its epidemic. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 262, 113261.

- Keller, C.J. Courage, Psychological Well-being, and Somatic Symptoms. Ph.D. Thesis, Seattle Pacific University, Seattle, WA, USA, 13 April 2016. Available online: https://digitalcommons.spu.edu/cpy_etd/17 (accessed on 10 July 2017).

- DeLongis, A.; Folkman, S.; Lazarus, R.S. The impact of daily stress on health and mood: Psychological and social resources as mediators. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 486.

- Masten, A.S. Global Perspectives on Resilience in Children and Youth. Child. Dev. 2014, 85, 6–20.

- Overton, W.F. A new paradigm for developmental science: Relationism and relational-developmental systems. App. Dev. Sci. 2013, 17, 94–107.

- Wright, M.O.D.; Masten, A.S.; Narayan, A.J. Resilience processes in development: Four waves of research on positive adaptation in the context of adversity. In Handbook of Resilience in Children; Goldstein, S., Brooks, R.B., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 15–37.

- Ben-Sira, Z. Potency: A stress-buffering link in the coping-stress-disease relationship. Sot. Sci. Med. 1985, 21, 397–406.

- Lev-Wiesel, R. Enhancing potency among male adolescents at risk to drug abuse: An action research. Child Adolesc. Soc. Work. J. 2009, 26, 383–398.

- Bhattacharyya, A.; Lev-Wiesel, R.; Banerjee, M. Roles of Emotional Reactions and Potency in Coping with Abusive Experiences of Indian Adolescent. J. Child Adolesc. Trauma 2020, 14, 61–72.

- Lev-Wiesel, R. Living under the threat of relocation: Different buffering effects of personal coping resources on men and women. Marriage Fam. Rev. 1999, 29, 97–108.

- Ladipo, M.M.; Obimakinde, A.M.; Irabor, A.E. Familial and socio-economic correlates of somatisation disorder. Afr. J. Prim. Health Care Fam. Med. 2015, 7, 1–8.

- Wethington, E.; Glanz, K.; Schwartz, M.D. Stress, coping, and health behavior. Health Behav. Theory Res. Pract. 2015, 223, 242.

- Muñoz, L.R. Graduate student self-efficacy: Implications of a concept analysis. J. Prof. Nurs. 2020, 37, 112–121.

- Wallston, K.A. Control Beliefs: Health Perspectives. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 819–821.

- Ross, C.E.; Mirowsky, J. Alienation: Psychosociological Tradition. In International Encyclopaedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; p. 2.

- Deflem, M. Anomie, Strain, and Opportunity Structure. In The Handbook of the History and Philosophy of Criminology; Triplett, R.A., Ed.; Wiley, Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 140–155.