| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | David Fryburg | -- | 2941 | 2023-06-12 16:14:21 | | | |

| 2 | Dean Liu | -3 word(s) | 2938 | 2023-06-13 03:02:42 | | |

Video Upload Options

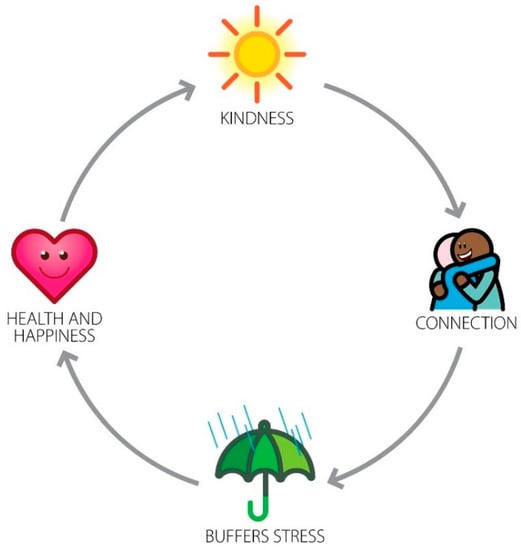

The healthcare workplace is a high-stress environment. All stakeholders, including patients and providers, display evidence of that stress. High stress has several effects. Even acutely, stress can negatively affect cognitive function, worsening diagnostic acumen, decision-making, and problem-solving. It decreases helpfulness. As stress increases, it can progress to burnout and more severe mental health consequences, including depression and suicide. One of the consequences (and causes) of stress is incivility. Both patients and staff can manifest these unkind behaviors, which in turn have been shown to cause medical errors. The human cost of errors is enormous, reflected in thousands of lives impacted every year. The economic cost is also enormous, costing at least several billion dollars annually in the US alone. The warrant for promoting kindness, therefore, is enormous. Kindness creates positive interpersonal connections, which, in turn, buffers stress and fosters resilience. Kindness, therefore, is not just a nice thing to do: it is critically important in the workplace. Ways to promote kindness, including leadership modeling positive behaviors as well as the deterrence of negative behaviors, are essential.

1. Disruptive Behaviors in the Health Care Workplace

2. Kindness Is Not Just about Being Nice

3. Promoting Kindness and Connection in the Health Care Workplace

References

- Jacobs, A.K. Rebuilding an Enduring Trust in Medicine. Circulation 2005, 111, 3494–3498.

- Wiegmann, D.A.; ElBardissi, A.W.; Dearani, J.A.; Daly, R.C.; Sundt, T.M., 3rd. Disruptions in surgical flow and their relationship to surgical errors: An exploratory investigation. Surgery 2007, 142, 658–665.

- Leonard, M.W.; Frankel, A.S. Role of effective teamwork and communication in delivering safe, high-quality care. Mt. Sinai J. Med. 2011, 78, 820–826.

- Leonard, M.; Graham, S.; Bonacum, D. The human factor: The critical importance of effective teamwork and communication in providing safe care. Qual. Saf. Health Care 2004, 13 (Suppl. S1), i85–i90.

- Paulmann, S.; Furnes, D.; Bøkenes, A.M.; Cozzolino, P.J. How Psychological Stress Affects Emotional Prosody. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0165022.

- Glavin, R.J. Human performance limitations (communication, stress, prospective memory and fatigue). Best Pract. Res. Clin. Anaesthesiol. 2011, 25, 193–206.

- Mehrabian, A.; Ferris, S.R. Inference of attitudes from nonverbal communication in two channels. J. Consult. Psychol. 1967, 31, 248–252.

- Kappen, M.; van der Donckt, J.; Vanhollebeke, G.; Allaert, J.; Degraeve, V.; Madhu, N.; Van Hoecke, S.; Vanderhasselt, M.-A. Acoustic speech features in social comparison: How stress impacts the way you sound. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 22022.

- Carter, M.; Thompson, N.; Crampton, P.; Morrow, G.; Burford, B.; Gray, C.; Illing, J. Workplace bullying in the UK NHS: A questionnaire and interview study on prevalence, impact and barriers to reporting. BMJ Open 2013, 3, e002628.

- Carlasare, L.E.; Hickson, G.B. Whose Responsibility Is It to Address Bullying in Health Care? AMA J. Ethics 2021, 23, E931–E936.

- Andersson, L.M.; Pearson, C.M. Tit for Tat? The Spiraling Effect of Incivility in the Workplace. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1999, 24, 452–471.

- Dabekaussen, K.F.A.A.; Scheepers, R.A.; Heineman, E.; Haber, A.L.; Lombarts, K.M.J.M.H.; Jaarsma, D.A.D.C.; Shapiro, J. Health care professionals’ perceptions of unprofessional behaviour in the clinical workplace. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0280444.

- Cook, A.F.; Arora, V.M.; Rasinski, K.A.; Curlin, F.A.; Yoon, J.D. The prevalence of medical student mistreatment and its association with burnout. Acad. Med. 2014, 89, 749–754.

- Kemper, K.J.; Schwartz, A. Bullying, Discrimination, Sexual Harassment, and Physical Violence: Common and Associated With Burnout in Pediatric Residents. Acad. Pediatr. 2020, 20, 991–997.

- Leape, L.L.; Shore, M.F.; Dienstag, J.L.; Mayer, R.J.; Edgman-Levitan, S.; Meyer, G.S.; Healy, G.B. Perspective: A culture of respect, part 1: The nature and causes of disrespectful behavior by physicians. Acad. Med. 2012, 87, 845–852.

- Rosenstein, A.H.; O’Daniel, M. A survey of the impact of disruptive behaviors and communication defects on patient safety. Jt. Comm. J. Qual. Patient Saf. 2008, 34, 464–471.

- Einarsen, S.; Hoel, H.; Notelaers, G. Measuring exposure to bullying and harassment at work: Validity, factor structure and psychometric properties of the Negative Acts Questionnaire-Revised. Work. Stress 2009, 23, 24–44.

- Westbrook, J.; Sunderland, N.; Li, L.; Koyama, A.; McMullan, R.; Urwin, R.; Churruca, K.; Baysari, M.T.; Jones, C.; Loh, E.; et al. The prevalence and impact of unprofessional behaviour among hospital workers: A survey in seven Australian hospitals. Med. J. Aust. 2021, 214, 31–37.

- Lim, S.; Goh, E.Y.; Tay, E.; Tong, Y.K.; Chung, D.; Devi, K.; Tan, C.H.; Indran, I.R. Disruptive behavior in a high-power distance culture and a three-dimensional framework for curbing it. Health Care Manag. Rev. 2022, 47, 133–143.

- Oppel, E.M.; Mohr, D.C.; Benzer, J.K. Let’s be civil: Elaborating the link between civility climate and hospital performance. Health Care Manag. Rev. 2019, 44, 196–205.

- Cooper, W.O.; Guillamondegui, O.; Hines, O.J.; Hultman, C.S.; Kelz, R.R.; Shen, P.; Spain, D.A.; Sweeney, J.F.; Moore, I.N.; Hopkins, J.; et al. Use of Unsolicited Patient Observations to Identify Surgeons with Increased Risk for Postoperative Complications. JAMA Surg. 2017, 152, 522–529.

- Lagoo, J.; Berry, W.R.; Miller, K.; Neal, B.J.; Sato, L.; Lillemoe, K.D.; Doherty, G.M.; Kasser, J.R.; Chaikof, E.L.; Gawande, A.A.; et al. Multisource Evaluation of Surgeon Behavior Is Associated with Malpractice Claims. Ann. Surg. 2019, 270, 84–90.

- Rowe, S.G.; Stewart, M.T.; Van Horne, S.; Pierre, C.; Wang, H.; Manukyan, M.; Bair-Merritt, M.; Lee-Parritz, A.; Rowe, M.P.; Shanafelt, T.; et al. Mistreatment Experiences, Protective Workplace Systems, and Occupational Distress in Physicians. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2210768.

- Viotti, S.; Converso, D.; Hamblin, L.E.; Guidetti, G.; Arnetz, J.E. Organisational efficiency and co-worker incivility: A cross-national study of nurses in the USA and Italy. J. Nurs. Manag. 2018, 26, 597–604.

- Gascon, S.; Leiter, M.P.; Andrés, E.; Santed, M.A.; Pereira, J.P.; Cunha, M.J.; Albesa, A.; Montero-Marín, J.; García-Campayo, J.; Martínez-Jarreta, B. The role of aggressions suffered by healthcare workers as predictors of burnout. J. Clin. Nurs. 2013, 22, 3120–3129.

- Hatfield, M.; Ciaburri, R.; Shaikh, H.; Wilkins, K.M.; Bjorkman, K.; Goldenberg, M.; McCollum, S.; Shabanova, V.; Weiss, P. Addressing Mistreatment of Providers by Patients and Family Members as a Patient Safety Event. Hosp. Pediatr. 2022, 12, 181–190.

- Li, Y.-L.; Li, R.-Q.; Qiu, D.; Xiao, S.-Y. Prevalence of Workplace Physical Violence against Health Care Professionals by Patients and Visitors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 299.

- Weber-Shandwick. Civility in Americal 2019: Solutions for Tomorrow; Weber-Shandwick: New York, NY, USA, 2019.

- Philips, T.; Stuart, H. An Age of Incivility: Understanding the New Politics; Policy Exchange: London, UK, 2018.

- Schilpzand, P.; De Pater, I.E.; Erez, A. Workplace incivility: A review of the literature and agenda for future research. J. Organ. Behav. 2016, 37, S57–S88.

- Loh, J.M.I.; Saleh, A. Lashing out: Emotional exhaustion triggers retaliatory incivility in the workplace. Heliyon 2022, 8, E08694.

- Cohen, S.; Wills, T.A. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol. Bull. 1985, 98, 310–357.

- Aknin, L.B.; Dunn, E.W.; Norton, M.I. Happiness Runs in a Circular Motion: Evidence for a Positive Feedback Loop between Prosocial Spending and Happiness. J. Happiness Stud. 2012, 13, 347–355.

- Ekman, P. Darwin’s compassionate view of human nature. JAMA 2010, 303, 557–558.

- Keltner, D. Born to Be Good: The Science of a Meaningful Life; W. W. Norton & Co.: New York, NY, USA, 2009; p. 209.

- Fryburg, D.A. Kindness as a Stress Reduction-Health Promotion Intervention: A Review of the Psychobiology of Caring. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2022, 16, 89–100.

- Kozlowski, D.; Hutchinson, M.; Hurley, J.; Rowley, J.; Sutherland, J. The role of emotion in clinical decision making: An integrative literature review. BMC Med. Educ. 2017, 17, 255.

- LeBlanc, V.R.; McConnell, M.M.; Monteiro, S.D. Predictable chaos: A review of the effects of emotions on attention, memory and decision making. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. Theory Pract. 2015, 20, 265–282.

- Liu, G.; Chimowitz, H.; Isbell, L.M. Affective influences on clinical reasoning and diagnosis: Insights from social psychology and new research opportunities. Diagnosis 2022, 9, 295–305.

- Trzeciak, S.; Mazzarelli, A.; Booker, C. Compassionomics: The Revolutionary Scientific Evidence That Caring Makes a Difference; Studer Group: Pensacola, FL, USA, 2019.

- Shanafelt, T.D.; Noseworthy, J.H. Executive Leadership and Physician Well-being: Nine Organizational Strategies to Promote Engagement and Reduce Burnout. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2017, 92, 129–146.

- Regehr, C.; Glancy, D.; Pitts, A.; LeBlanc, V.R. Interventions to reduce the consequences of stress in physicians: A review and meta-analysis. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2014, 202, 353–359.

- Arnetz, J.E.; Hamblin, L.; Russell, J.; Upfal, M.J.; Luborsky, M.; Janisse, J.; Essenmacher, L. Preventing Patient-to-Worker Violence in Hospitals: Outcome of a Randomized Controlled Intervention. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2017, 59, 18–27.

- Murray, M.; Murray, L.; Donnelly, M. Systematic review of interventions to improve the psychological well-being of general practitioners. BMC Fam. Pract. 2016, 17, 36.

- Patel, A.; Plowman, S. The Increasing Importance of a Best Friend at Work; Gallup: Washington, DC, USA, 2022.

- Holt-Lunstad, J. Fostering Social Connection in the Workplace. Am. J. Health Promot. 2018, 32, 1307–1312.

- Leape, L.L.; Shore, M.F.; Dienstag, J.L.; Mayer, R.J.; Edgman-Levitan, S.; Meyer, G.S.; Healy, G.B. Perspective: A culture of respect, part 2: Creating a culture of respect. Acad. Med. 2012, 87, 853–858.

- Ellithorpe, M.E.; Ewoldsen, D.R.; Oliver, M.B. Elevation (sometimes) increases altruism: Choice and number of outcomes in elevating media effects. Psychol. Pop. Media Cult. 2015, 4, 236–250.

- Algoe, S.B.; Haidt, J. Witnessing excellence in action: The ‘other-praising’ emotions of elevation, gratitude, and admiration. J. Posit. Psychol. 2009, 4, 105–127.

- Freeman, D.; Aquino, K.; McFerran, B. Overcoming beneficiary race as an impediment to charitable donations: Social dominance orientation, the experience of moral elevation, and donation behavior. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2009, 35, 72–84.

- Fryburg, D.A.; Ureles, S.D.; Myrick, J.G.; Carpentier, F.D.; Oliver, M.B. Kindness Media Rapidly Inspires Viewers and Increases Happiness, Calm, Gratitude, and Generosity in a Healthcare Setting. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 591942.