Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Rosalba D'Onofrio | -- | 1906 | 2023-06-11 22:51:59 | | | |

| 2 | Catherine Yang | Meta information modification | 1906 | 2023-06-12 02:45:42 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

D’onofrio, R.; Camaioni, C.; Mugnoz, S. The Utility of Joint SECAP Plans. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/45428 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

D’onofrio R, Camaioni C, Mugnoz S. The Utility of Joint SECAP Plans. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/45428. Accessed February 07, 2026.

D’onofrio, Rosalba, Chiara Camaioni, Stefano Mugnoz. "The Utility of Joint SECAP Plans" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/45428 (accessed February 07, 2026).

D’onofrio, R., Camaioni, C., & Mugnoz, S. (2023, June 11). The Utility of Joint SECAP Plans. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/45428

D’onofrio, Rosalba, et al. "The Utility of Joint SECAP Plans." Encyclopedia. Web. 11 June, 2023.

Copy Citation

The “Joint Sustainable Energy and Climate Action Plans” (Joint SECAPs) introduced by the Covenant of Mayors (CoM) are voluntary tools that favour a joint approach to energy planning and climate change mitigation/adaptation among municipalities in the same territorial area.

Joint SECAPs

climate adaptation

multilevel governance

local government

1. Introduction

Although climate change is a global problem and much of the responsibility for initiating actions to address this challenge is shared politically on the international, national, and regional levels, such actions must be implemented on the local level [1][2][3].

Cities and municipalities are key in promoting mitigation and adaptation actions [4][5][6] and play a crucial role in pursuing sustainability, equitably distributing resources, and promoting new climate policies, low-carbon technologies, and sustainable infrastructure [7]. Local governments play this role in three main ways [8]: (a) leading the local community (by developing and implementing local policies and regulations that pursue objectives beyond national targets); (b) acting as an infrastructure manager and/or owner (by encouraging energy efficiency in public buildings and promoting sustainable products and services through green public procurement) [9][10]; and (c) sharing information with the local community on experiences and examples to improve knowledge and awareness about climate change [11].

European adaptation policies have progressed quickly in recent years with the introduction of the European Green Deal [12], the new EU Adaptation Strategy [13], and the Climate Law of 2021 [14]. Scientific research has also dealt extensively with adaptation [15][16], studying a variety of aspects including the spatial aspect of plans [17]; indicators and metrics for verifying their effectiveness [18]; the reasons for the success of some experiments [19]; the importance of a long-term perspective [20]; the role of the local community [21][22]; and the role of cities [23]. Nevertheless, measures and plans dealing with mitigation are still favoured with regard to operations [24][25]. This propensity for mitigation rather than adaptation was clearly highlighted a few years ago by a survey of 885 European cities [26]. The survey showed that about 66% of EU cities with a population of at least 50,000 had a local mitigation plan, 26% had an adaptation plan, only 17% had a joint mitigation/adaptation plan, and about 33% had no local climate plan. Most research in recent years has regarded large cities [27][28] and the barriers to developing and planning policies and actions for adaptation [29][30][31][32]. Small cities and municipalities instead do not seem able to effectively address climate risks due to a lack of resources [30], the necessary skills [33], and the lack of policy tools that larger cities and entities have [29].

A good observatory for investigating these difficulties, especially with respect to adaptation and small municipalities, is the ‘Covenant of Mayors’ (CoM). This is an initiative by the European Commission, the role of which is to encourage local entities to commit themselves to climate actions, with growing participation in recent years [33][34][35]. This network of municipalities was created in 2008 and integrated into the Covenant of Mayors for Climate and Energy and then into the Global Covenant of Mayors for Climate and Energy (GcoM) in 2017.

Official documents and the Covenant of Mayors offer a preferential look at the policies implemented by local authorities, as shown by the recent Joint Research Centre (JRC) report ‘Covenant of Mayors: 2021 assessment. Climate change mitigation and adaptation at local level’ [36]. This report underlines how the large majority of signers (63.2% of 10,500 signatories as of 2021) have committed themselves to reaching objectives that do not include adaptation, but only mitigation. This delay in addressing adaptation is associated with the difficulty of local entities to develop actions in sectors that hold jurisdiction or limited financial capacity and the difficulty of monitoring, given that most action plans do not include monitoring reports in the current phase (only 69 of 953 action plans). This report also confirmed that small towns and municipalities have very limited capacity for action with regard to adaptation [36].

Faced with these documented difficulties, especially in small municipalities and cities, some researchers argue that it is necessary to increase the governance capacity of adaptation by proposing a strategy to reconcile the needs of different actors and promote collective action and coordination [37]. To do so, a good opportunity may be the creation of municipal climate networks to support adaptation efforts [38][39][40]. Building networks would allow for the pooling of resources, with the exchange of crucial information on adaptation policies and actions and mutual learning [30]. Networking [41][42] could facilitate the implementation of custom solutions based on local needs [43], strengthen local communities, and increase the ‘environmental awareness’ of different stakeholders [44]. The results of this strategy could also lead to solutions to common problems [30] and promote adaptation actions integrated into decisionmaking processes [45].

Networking to build common, shared actions to tackle climate change is one of the objectives of the Joint SECAP Plans (Sustainable Energy and Climate Action Plans) [46]. These local, voluntary plans promoted by the CoM follow a joint approach to energy planning and mitigation of/adaptation to climate change in surrounding cities to obtain results that are more effective than in isolated cases. The municipalities involved would, therefore, benefit from economies of scale, with evident savings in personnel and resources [46].

2. The Potential of Joint SECAPs and Their Implementation in Italy

Despite various difficulties, according to the New EU Adaptation Strategy on Adaptation to Climate Change [13], the local level is the ‘bedrock of adaptation’ and local authorities play a crucial role in implementing national adaptation strategies, promoting smarter, quicker, and more systematic adaptation and spreading awareness about adaptation in all areas of intervention [23].

Joint SECAPs, which are recommended by the CoM for small/medium-sized municipalities within the same territorial area, cover a population of roughly less than 10,000 inhabitants per municipality, although the tool can also be used for larger agglomerations [47].

Under the CoM, SECAPs are strategic documents that dictate guidelines on procedures to implement in the fight against climate change [46], although without defining binding precepts, so the actions do not, for example, directly affect territorial governance regulations [48].

Viewed from this perspective, combating climate change would be a challenge to solve not on the local scale, but in other areas. These aspects lead to potential conflict. While the construction and management of the plan on the local level are desirable, the involvement of entities, actors, and tools pertaining to other competencies and other governance levels is required. Resolving potential conflict requires the promotion and reinforcement of coordination activities and a clear division of tasks and responsibilities for the different public actors participating in the process [4][49].

On the other hand, the joint construction of SECAPs could strengthen the bargaining power of small municipalities vis-à-vis higher level bodies and territorial stakeholders, interpreting the perspectives regarding the sustainability of the different stakeholders and actors, becoming more open to debate in order to achieve short- and long-term adaptation goals [50][51][52], and transforming current barriers into factors for enabling action and change [53]. By promoting Joint SECAPs, the difficulties found in small municipalities would be resolved. Such difficulties include

-

The fragmentation of skills among different sectors of the public administration and the absence of coordination between them [56].

-

The sector-based approach of SECAPs and the lack of an integrated urban vision do not encourage their consideration as institutional tools on par with urban plans, regulations, etc. They are often simply considered as tools for planning and financing ordinary interventions in urban areas [44].

The European Horizon 2020 research ‘Path2LC’ identifies joint planning as a possible solution to overcome barriers to the implementation of SECAPs [57]. In its recent report entitled ‘D4.9 SE(C)APs: From local planning to concrete action Barriers, success factors and decision processes’, the plans were analysed by the network of researchers (five European countries and followers), with the result that in most cases only partial results were achieved, the so-called ‘low-hanging fruit’ [57]. This means that to date, only easy-to-implement measures have been introduced, disregarding ones that are more strategic.

These measures include, for example, those regarding education or raising awareness among some bands of the population [57]. According to the Path2LC project, this lack of consideration of the role of SECAPs is due to the scarce skills and motivation of stakeholders, the inability to integrate these plans within ordinary territorial management, powerlessness when faced with the jungle of financing available to implement the action plans, etc.

One very effective solution indicated by this research is the ‘Learning Municipality Networks’ approach, that is, exchange networks activated among the different relevant administrations to define objectives and common actions. In support of this network, the project involves a series of tools such as webinars, peer-to-peer sessions (inter-regional and inter-national), expert input, and tailored workshops, as well as an open-source knowledge base. The underlying idea is to overcome obstacles by exchanging knowledge and experiences between the municipalities and cities participating in the network, improving coordination between different sectors of the public administration, cooperation with civil society, and the availability of the planning and monitoring tools necessary to develop and reach the objectives set in the plans.

While Joint SECAPs as conceived by the CoM are only referenced indirectly in the Path2LC project, they are more explicitly called on by the Italian Institute for Environmental Protection and Research (ISPRA) in its ‘Report 2020 on the State of activation of the Covenant of Mayors’ [58]. ISPRA states that it is essential to use SECAPs to strengthen joint action on behalf of small Italian municipalities. It, therefore, calls for incentives to encourage the submission of Joint SECAPs to reach minimum population thresholds, at least those above 3000 inhabitants.

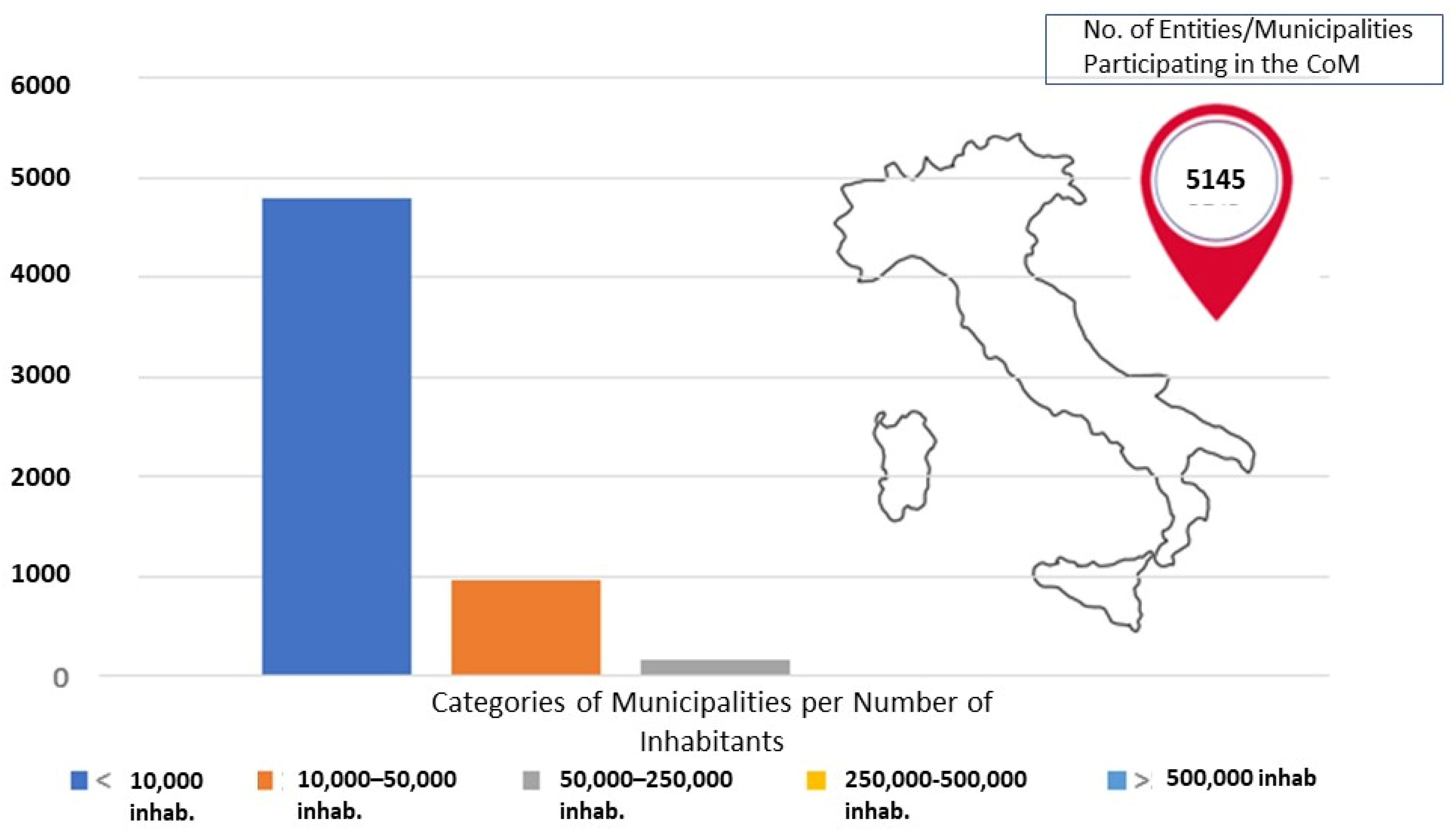

The call by ISPRA is very important for Italy. Although the country has not developed a national law to impose the development of climate plans, it participates significantly in the CoM (Figure 1), with 5145 municipal signatories, the vast majority of which (4968) have less than 50,000 inhabitants (Figure 1). Although a large number of Italian local authorities have made commitments with respect to adaptation, few have addressed this issue in their SECAP (Table 1).

Figure 1. Total Italian signatories and classes of entities per number of inhabitants. March 2023. Source: CoM, https://eu-mayors.ec.europa.eu/en/signatories, accessed on 3 March 2023. Figure produced by the authors.

Table 1. Signatories of the Covenant of Mayors as of 2021 and their commitments. Source: ISPRA, http://bogelso.sinanet.isprambiente.it/temi/cambiamenti-climatici/il-patto-dei-sindaci-per-il-clima-e-lenergia, accessed on 3 March 2023. Table produced by the authors.

| Italian Signatories of the Covenant of Mayors | Signatories Who Have Submitted an Action Plan | Signatories That Have Monitored the Action Plan | Signatories That Have Made Commitments with Respect to Adaptation | TOT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <10,000 residents | 2497 (70%) | 703 (20%) | 354 (10%) | 3554 |

| 10,000–50,000 | 686 (60%) | 279 (24%) | 195 (16%) | 1160 |

| 50,000–250,000 | 115 (52%) | 57 (26%) | 47 (22%) | 219 |

| 250,000–500,000 | 9 (50%) | 4 (22%) | 5 (28%) | 18 |

| >500,000 | 5 (38%) | 4 (31%) | 4 (31%) | 13 |

In the above-mentioned report, ISPRA attributes the scant participation and performance of small and medium-small municipalities to sudden institutional changes, the widespread lack of qualified personnel for implementation, monitoring, and evaluation of the results of the actions taken, fragmentation among different offices and departments in the public administration, the lack of data and skills important for climate change initiatives, and the frequent lack of coordination and political leadership to guarantee the necessary consistency.

The report, therefore, recommends specific promotion and support for small municipalities to pursue the following:

-

Greater harmonisation of data and methods;

-

Greater sharing of technical skills as well as the necessary personnel, not only for adherence and preparing the plan, but also for the expected monitoring stages;

-

More adequate management of the issues of climate-change adaptation by developing more stringent guidelines on the means of stating and calculating emissions;

-

Strengthening promotional activities through the use of mechanisms that encourage the presentation of Joint SECAPs.

References

- Baker, I.; Peterson, A.; Brown, G.; McAlpine, C. Local government response to the impacts of climate change: An evaluation of local climate adaptation plans. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2012, 107, 127–136.

- Bebbington, J.; Unerman, J.; O’Dwyer, B. Sustainability Accounting and Accountability; Taylor and Francis: London, UK, 2014.

- Hoppe, T.; van den Berg, M.M.; Coenen, F.H. Reflections on the Uptake of Climate Change Policies by Local Governments: Facing the Challenges of Mitigation and Adaptation. Energy Sustain. Soc. 2014, 4, 8. Available online: http://www.energsustainsoc.com/content/4/1/8 (accessed on 23 May 2023).

- Amundsen, H.; Hovelsrud, G.K.; Aall, C.; Karlsson, M.; Westskog, H. Local governments as drivers for societal transformation: Towards the 1.5 °C ambition. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2018, 31, 23–29.

- Aguiar, F.C.; Bentz, J.; Silva, J.M.N.; Fonseca, A.L.; Swart, R.; Santos, F.D.; Penha-Lopes, G. Adaptation to climate change at local level in Europe: An overview. Environ. Sci. Policy 2018, 86, 38–63.

- Cheung, T.T.T.; Oßenbrügge, J. Urban energy transitions and climate change; actions, relations and local dependences in Germany. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2020, 69, 101728.

- Gouldson, A.P.; Colenbrander, S.; Sudmant, A.; Godfrey, N.; Millward-Hopkins, J.; Fang, W.; Zhao, X. Accelerating Low-Carbon Development in the Worlds Cities. New Clim. Econ. 2015. Available online: https://www.newclimateeconomy.report (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- Van Staden, M.; Musco, F. (Eds.) Local Governments and Climate Change—Sustainable Energy Planning and Implementation in Small and Medium Sized Communities, 1st ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2010; Volume 39.

- Bryngemark, E.; Söderholm, P.; Thörn, M. The adoption of green public procurement practices: Analytical challenges and empirical illustration on Swedish municipalities. Ecol. Econ. 2023, 204, 107655.

- Kordos, V.; Golubovic, V.; Zunac, A.G. Green Public Procurement, Economic and Social Development: Book of Proceedings—83 rd International Scientific Conference on Economic and Social Development—“Green Marketing”; ZBW—Leibniz-Informationszentrum Wirtschaft/Leibniz Information Centre for Economics: Kiel, Germany, 2022.

- Carlson, D. Preparing for Climate Change—An Implementation Guide for Local Governments in British Columbia. 2012. Available online: https://www.wcel.org/publication/preparing-climate-change-implementation-guide-local-governments-british-columbia (accessed on 16 March 2022).

- European Commission. The European Green Deal. 2019. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:b828d165-1c22-11ea-8c1f-01aa75ed71a1.0002.02/DOC_1&format=PDF (accessed on 23 May 2023).

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. Forging a Climate-Resilient Europe—The New EU Strategy on Adaptation to Climate Change. 2021. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=COM:2021:82:FIN (accessed on 23 May 2023).

- Official Journal of the European Union. Regulation (EU) 2021/1119 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 June 2021 Establishing the Framework for Achieving Climate Neutrality and Amending Regulations (EC) No 401/2009 and (EU) 2018/1999 (‘European Climate Law’). 2021. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/homepage.html (accessed on 23 May 2023).

- Woodruff, S.C.; Meerow, S.; Stults, M.; Wilkins, C. Adaptation to Resilience Planning: Alternative Pathways to Prepare for Climate Change. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2018, 42, 64–75.

- UNFCCC. What Do Adaptation to Climate Change and Climate Resilience Mean? 2022. Available online: https://unfccc.int/topics/adaptation-and-resilience/the-big-picture/what-do-adaptation-toclimate-change-and-climate-resilience-mean (accessed on 23 May 2023).

- Thoidou, E. Spatial Planning and Climate Adaptation: Challenges of Land Protection in a Peri-Urban Area of the Mediterranean City of Thessaloniki. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4456.

- Moser, S.C.; Boykoff, M.T. Successful Adaptation to Climate Change Linking Science and Policy in a Rapidly Changing World; Routledge: London, UK, 2013.

- Rivas, S.; Urraca, R.; Bertoldi, P.; Thiel, C. Towards the EU Green Deal: Local key factors to achieve ambitious 2030 climate targets. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 320, 128878.

- Filho, W.L.; Shiel, C.; Paço, A.; Mifsud, M.; Ávila, L.V.; Brandli, L.L.; Molthan-Hill, P.; Pace, P.; Azeiteiro, U.M.; Vargas, V.R.; et al. Sustainable Development Goals and sustainability teaching at universities: Falling behind or getting ahead of the pack? J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 232, 285–294.

- Carmen, E.; Fazey, I.; Ross, H.; Bedinger, M.; Smith, F.M.; Prager, K.; McClymont, K.; Morrison, D. Building community resilience in a context of climate change: The role of social capital. AMBIO 2022, 51, 1371–1387.

- Fazey, I.; Carmen, E.; Ross, H.; Rao-Williams, J.; Hodgson, A.; Searle, B.A.; AlWaer, H.; Kenter, J.O.; Knox, K.; Butler, J.R.A.; et al. Social dynamics of community resilience building in the face of climate change: The case of three Scottish communities. Sustain. Sci. 2021, 16, 1731–1747.

- EEA. EEA Report “Urban Adaptation in Europe: How Cities and Towns Respond to Climate Change”. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/358264183_Urban_adaptation_in_Europe_how_cities_and_towns_respond_to_climate_change (accessed on 23 May 2023).

- Reckien, D.; Flacke, J.; Dawson, R.J.; Heidrich, O.; Olazabal, M.; Foley, A.; Hamann, J.J.-P.; Orru, H.; Salvia, M.; De Gregorio Hurtado, S.; et al. Climate change response in Europe: What’s the reality? Analysis of adaptation and mitigation plans from 200 urban areas in 11 countries. Clim. Chang. 2014, 122, 331–340.

- De Oliveira, J.A.P.; Doll, C.N.H.; Kurniawan, T.A.; Geng, Y.; Kapshe, M.; Huisingh, D. Promoting win–win situations in climate change mitigation, local environmental quality and development in Asian cities through co-benefits. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 58, 1–6.

- Reckien, D.; Salvia, M.; Heidrich, O.; Church, J.M.; Pietrapertosa, F.; De Gregorio-Hurtado, S.; D’Alonzo, V.; Foley, A.; Simoes, S.G.; Lorencová, E.K.; et al. How are cities planning to respond to climate change? Assessment of local climate plans from 885 cities in the EU-28. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 191, 207–219.

- Araos, M.; Berrang-Ford, L.; Ford, J.D.; Austin, S.E.; Biesbroek, R.; Lesnikowski, A. Climate change adaptation planning in large cities: A systematic global assessment. Environ. Sci. Policy 2016, 66, 375–382.

- Dupuis, J.; Biesbroek, R. Comparing apples and oranges: The dependent variable problem in comparing and evaluating climate change adaptation policies. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2013, 23, 1476–1487.

- Bausch, T.; Koziol, K. New Policy Approaches for Increasing Response to Climate Change in Small Rural Municipalities. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1894.

- Häußler, S.; Haupt, W. Climate change adaptation networks for small and medium-sized cities. SN Soc. Sci. 2021, 1, 262.

- Otto, A.; Kern, K.; Haupt, W.; Eckersley, P.; Thieken, A.H. Ranking local climate policy: Assessing the mitigation and adaptation activities of 104 German cities. Clim. Chang. 2021, 167, 5.

- Fitton, J.M.; Addo, K.A.; Jayson-Quashigah, P.-N.; Nagy, G.J.; Gutiérrez, O.; Panario, D.; Carro, I.; Seijo, L.; Segura, C.; Verocai, J.E.; et al. Challenges to climate change adaptation in coastal small towns: Examples from Ghana, Uruguay, Finland, Denmark, and Alaska. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2021, 212, 105787.

- Covenant of Mayors. Flashback: The Origins of the Covenant of Mayors. Available online: https://www.covenantofmayors.eu/about/covenant-initiative/origins-and-development.html (accessed on 1 April 2022).

- Bertoldi, P.; Rivas Calvete, S.; Kona, A.; Hernandez Gonzalez, Y.; Marinho Ferreira Barbosa, P.; Palermo, V.; Baldi, M.; Lo Vullo EMuntean, M. Covenant of Mayors: 2019 Assessment; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2020; ISBN 978-92-76-10721-7.

- Basso, M.; Tonin, S. The implementation of the Covenant of Mayors initiative in European cities: A policy perspective. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 78, 103596.

- Melica, G.; Treville, A.; Franco De Los Rios, C.; Baldi, M.; Monforti-Ferrario, F.; Palermo, V.; Ulpiani, G.; Ortega Hortelano, A.; Lo Vullo, E.; Marinho Ferreira Barbosa PBertoldi, P. Covenant of Mayors: 2021 Assessment; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2022.

- Van Popering-Verkerk, J.; Molenveld, A.; Duijn, M.; van Leeuwen, C.; van Buuren, A. A Framework for Governance Capacity: A Broad Perspective on Steering Efforts in Society. Adm. Soc. 2022, 54, 1767–1794.

- Hauge, L.; Hanssen, G.S.; Flyen, C. Multilevel networks for climate change adaptation—What works? Int. J. Clim. Chang. Strat. Manag. 2019, 11, 215–234.

- Landauer, M.; Juhola, S.; Klein, J. The role of scale in integrating climate change adaptation and mitigation in cities. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2019, 62, 741–765.

- Goh, K. Flows in formation: The global-urban networks of climate change adaptation. Urban Stud. 2020, 57, 2222–2240.

- Meijerink, S.; Stiller, S. What Kind of Leadership Do We Need for Climate Adaptation? A Framework for Analyzing Leadership Objectives, Functions, and Tasks in Climate Change Adaptation. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2013, 31, 240–256.

- Schmid, J.C.; Knierim, A.; Knuth, U. Policy-induced innovations networks on climate change adaptation—An ex-post analysis of collaboration success and its influencing factors. Environ. Sci. Policy 2016, 56, 67–79.

- Granberg, M.; Elander, I. Local Governance and Climate Change: Reflections on the Swedish Experience. Local Environ. 2007, 12, 537–548. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/235734847_Local_Governance_and_Climate_Change_Reflections_on_the_Swedish_Experience (accessed on 23 May 2023).

- Scorza, F.; Santopietro, L. A systemic perspective for the Sustainable Energy and Climate Action Plan (SECAP). Eur. Plan. Stud. 2021, 1–21.

- Laukkonen, J.; Blanco, P.K.; Lenhart, J.; Keiner, M.; Cavric, B.; Kinuthia-Njenga, C. Combining climate change adaptation and mitigation measures at the local level. Habitat Int. 2009, 33, 287–292.

- Bertoldi, P. (Ed.) Guidebook ‘How to Develop a Sustainable Energy and Climate Action Plan (SECAP)—PART 3—Policies, Key Actions, Good Practices for Mitigation and Adaptation to Climate Change and Financing SECAP(s)’; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2018.

- Covenant of Mayors. Quick Reference Guide. Joint Sustainable Energy & Climate Action Plan. 2017. Available online: https://www.covenantofmayors.eu/support/reporting.html (accessed on 23 May 2023).

- Torelli, G. Il Contrasto ai Cambiamenti Climatici nel Governo del Territorio. 2020. Available online: https://www.federalismi.it/nv14/articolo-documento.cfm?Artid=40908 (accessed on 23 May 2023).

- Koch, I.C.; Vogel, C.; Patel, Z. Institutional dynamics and climate change adaptation in South Africa. Mitig. Adapt. Strat. Glob. Chang. 2007, 12, 1323–1339.

- Shaw, A.; Sheppard, S.; Burch, S.; Flanders, D.; Wiek, A.; Carmichael, J.; Robinson, J.; Cohen, S. Making local futures tangible—Synthesizing, downscaling, and visualizing climate change scenarios for participatory capacity building. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2009, 19, 447–463.

- Bardsley, D.K.; Sweeney, S.M. Guiding climate change adaptation within vulnerable natural resource management systems. Environ. Manag. 2010, 45, 1127–1141.

- Corfee-Morlot, J.; Cochran, I.; Hallegatte, S.; Teasdale, P.-J. Multilevel risk governance and urban adaptation policy. Clim. Chang. 2011, 104, 169–197.

- Biesbroek, G.R.; Klostermann, J.E.M.; Termeer, C.J.A.M.; Kabat, P. On the nature of barriers to climate change adaptation. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2013, 13, 1119–1129.

- Göpfert, C.; Wamsler, C.; Lang, W. Enhancing structures for joint climate change mitigation and adaptation action in city administrations—Empirical insights and practical implications. City Environ. Interact. 2020, 8, 100052.

- Melica, G. Multilevel governance of sustainable energy policies: The role of regions and provinces to support the participation of small local authorities in the covenant of mayors. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 39, 729–739.

- Uyl, R.M.D.; Russel, D.J. Climate adaptation in fragmented governance settings: The consequences of reform in public administration. Environ. Politics 2022, 27, 341–361.

- Chassein, E.; Frank, V.S. Path2LC. D4.9 SE(C)APs: From Municipal Planning to Concrete Action Barriers, Success Factors and Decision Processes. 2021. Available online: https://www.path2lc.eu/the-project/ (accessed on 23 May 2023).

- Ispra. Stato di Attuazione del Patto dei Sindaci in Italia, Rapporti 316/2020. 2020. Available online: https://www.isprambiente.gov.it/it/pubblicazioni/rapporti/stato-di-attuazione-del-patto-dei-sindaci-in-italia (accessed on 23 May 2023).

More

Information

Subjects:

Area Studies

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

655

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

12 Jun 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No