Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Albert Fekete | -- | 1258 | 2023-05-25 06:31:35 | | | |

| 2 | Catherine Yang | Meta information modification | 1258 | 2023-05-25 07:13:52 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Fekete, A.; Sárospataki, M. Late Renaissance Garden Units. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/44810 (accessed on 08 February 2026).

Fekete A, Sárospataki M. Late Renaissance Garden Units. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/44810. Accessed February 08, 2026.

Fekete, Albert, Máté Sárospataki. "Late Renaissance Garden Units" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/44810 (accessed February 08, 2026).

Fekete, A., & Sárospataki, M. (2023, May 25). Late Renaissance Garden Units. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/44810

Fekete, Albert and Máté Sárospataki. "Late Renaissance Garden Units." Encyclopedia. Web. 25 May, 2023.

Copy Citation

The use of plants in Renaissance gardens is the subject of numerous studies and essays on botanical history in Europe. A garden unit was defined as a garden or garden section with distinct denomination and function (plant use). In the case of “Type A” sites, it can be identified as a total of three characteristic garden units on the basis of the archives, which occurred regularly in the examined Late Renaissance gardens: flower garden, vegetable garden, and orchard.

renaissance garden art

plant use

landscape architecture

historic garden

1. The Flower Garden

Mostly formal gardens planted with herbaceous flowers, often decorated with herbs, in regular order. Of the explored sites, 20 places are mentioned having flower gardens. Despite the fact that the flower garden was primarily decorative, it appears in many places together with kitchen gardens/allotments.

“The design of the flower garden depends also closely on the composition of the landscape, and is the reflection of a lifestyle, a perspective, a philosophy and a changing socio-economic environment. With their flowers, the late Renaissance gardens of the Carpathian Basin were also the gardens of reality and freedom, because of the pomp of the West and the Ottoman dependency of the East. The symbol of national freedom at this time is the garden, where in addition to the flowers, the splendor and comfort of the gazebos showed this real world and the arising thoughts aof future independence as reconcilable,”[1]

As Csoma and Tüdős pointed out (see above), the garden must be approached as a microcosm of the landscape, and gardening must be regarded as the forerunner of landscape transformation.

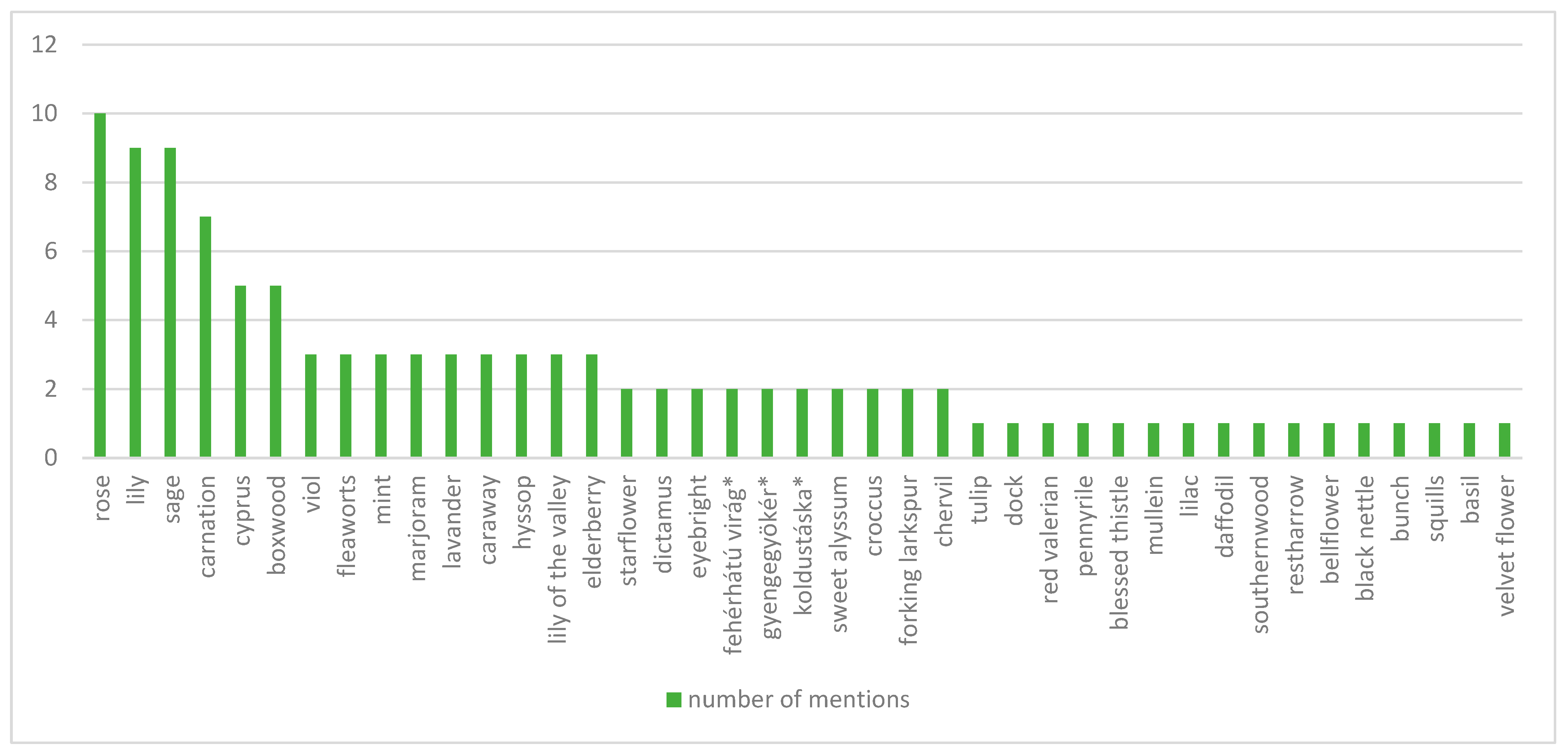

The researchers analyzed the inventories of the flower gardens in numerous cases thanks to the whole plant lists made of the species found there, but occasionally the species composition was not determined on the basis of live plants but from the prepared vegetable distillates. The researchers collected 42 mentions of different flowers (with ornamental, medicinal, or condimental effects). The taxonomic identification of three of these flowers (marked with an asterisk in the Figure 1) has not been possible based on the folk nomenclature used in archival materials, so it is not known exactly what kind of flowers they are. The flower species used in Transylvanian Late Renaissance gardens are shown in Figure 1. These show that the most common flowers are rose (mentioned in 10 locations), sage, lily (nine locations), and carnation (seven locations), while some flowers, such as lilac, bellflower spur flower, etc., are found only in a single garden.

Figure 1. Flower species used during 17–18th centuries in the Transylvanian residential gardens, mentioned in the inventories and other archival materials. The taxonomic identification of the species marked with an asterisk has not been possible based on the folk nomenclature used in archival materials, so it is not known exactly what kind of flowers they are. (Source: prepared by the Authors, based on [2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28]).

With regard to the varieties of the gardens, the highest number of flower species was mentioned in the case of Komána (Comana de Jos, 25 different flower species) and Uzdiszentpéter (Sanpetru de Campie, 24 flower species). The number of described flower species largely depended on the season in which the census was taken and the depth of plant knowledge of the census taker.

2. The Vegetable Garden

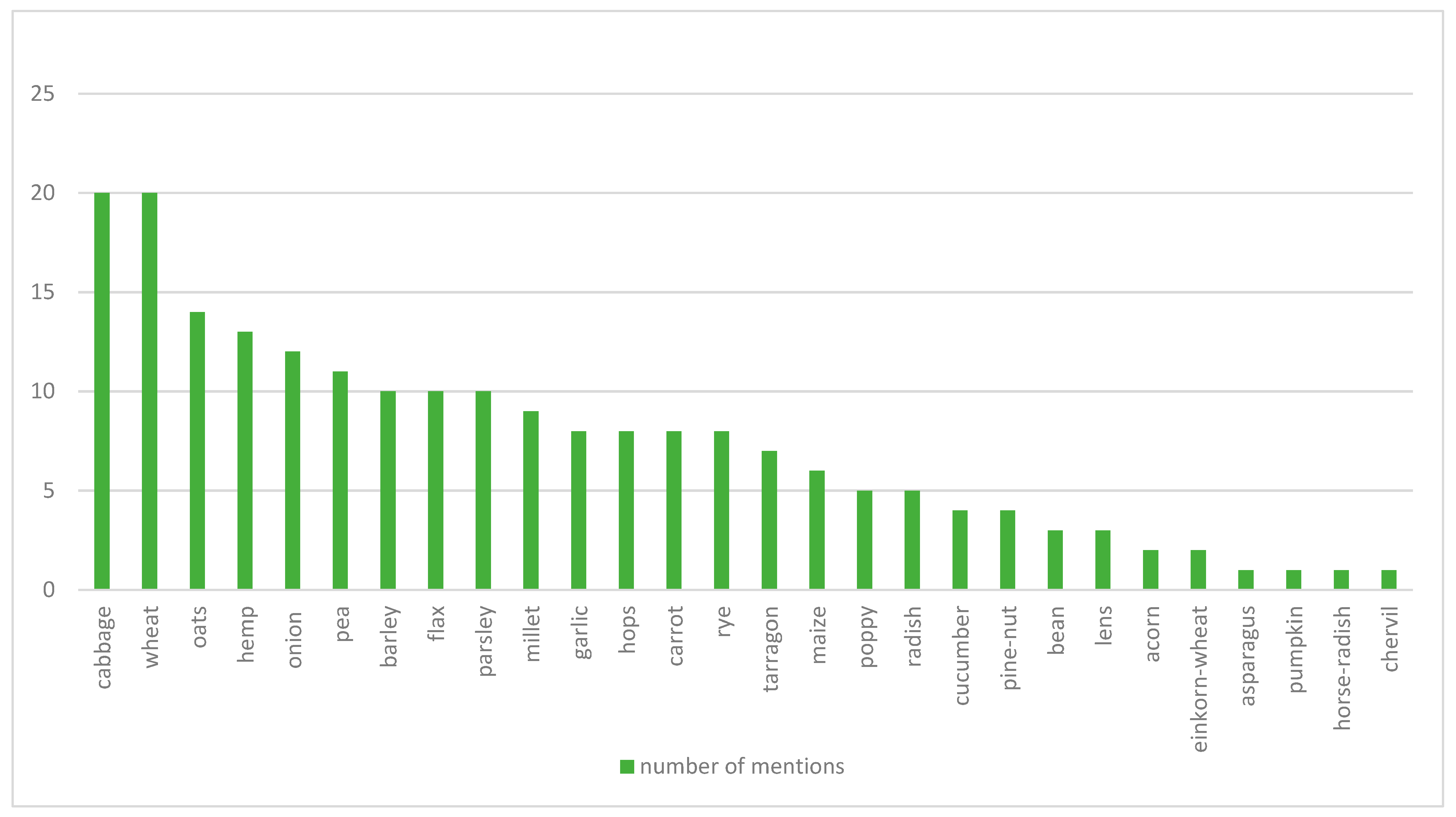

In general, a section of a geometrical garden was considered, mainly with ordered plantings of vegetables. Whenever one of the planted vegetables was in a larger proportion in the garden, the garden was named after the respective vegetable variety: cabbage garden in Görgényszentimre (Gurghiu, RO, 1652) or maize garden in Branyicska (Branisca, RO, 1757). The research identified vegetable gardens on 30 sites based on the descriptions. In these 30 locations, the researchers collected 30 mentions of different vegetables (and fodderplants). This highlights that the most common vegetable was the cabbage (mentioned in 20 locations), followed by some cereals and fodderplant species, e.g., wheat (20 locations), hemp (14 locations), and oats (13 locations), while some vegetables (such as pumpkin, chervil, asparagus etc.) were found only in a single garden (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Frequency of the most common vegetables, cereals and fodder plants used during the 17–18th centuries in the Transylvanian residential gardens, mentioned in the inventories and other archival materials (Source: prepared by the Authors, based on [2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28]).

3. The Orchard

A garden area where mostly fruit trees were planted was considered. Similar to the vegetable garden, the name of the garden area could also be the name of the dominant fruit variety here: sour cherry garden in Uzdiszentpéter (Sânpetru de Câmpie, RO, 1679), apple garden in Csíkkozmás (Cozmeni, RO, 1688), plum tree garden in Görgényszentimre (Gurghiu, RO, 1652). Orchards are mentioned in 39 locations in the descriptions. Orchards (or fruit trees) were very often found in flower garden compartiments, too. This category includes the following sites: Négerfalva (Negrilesti, RO, 1697), Borberek (Vurpar, RO 1701), Szásznádas (Nadasul Sasesc, RO 1712), Szászcsanád (Cenade, RO 1736) Marosszentkirály (Sancraiu de Mures, RO, 1753)(B. Nagy, 1970), Sárpatak (Sapartoc, RO, 1736), Nagyercse (Ercea, RO, 1750), Vajdahunyad (Hunedoara, RO, 1681), Branyicska (Branisca, RO, 1726), Szentbenedek (Manastirea, RO, 1784), and Mezőörményes (Urmenis, RO, 1721).

Figure 3 shows a terraced orchard garden on the castle hill from Segesvár (Sighisoara, RO), and some compartmented gardens organized in the manor courtyards (bottom, right), on the river shore, at the end of 17th century.

Figure 3. View of Schassburg the turn of 17/18 centuries, with representation of orchards and compartmented gardens (Source: [29]).

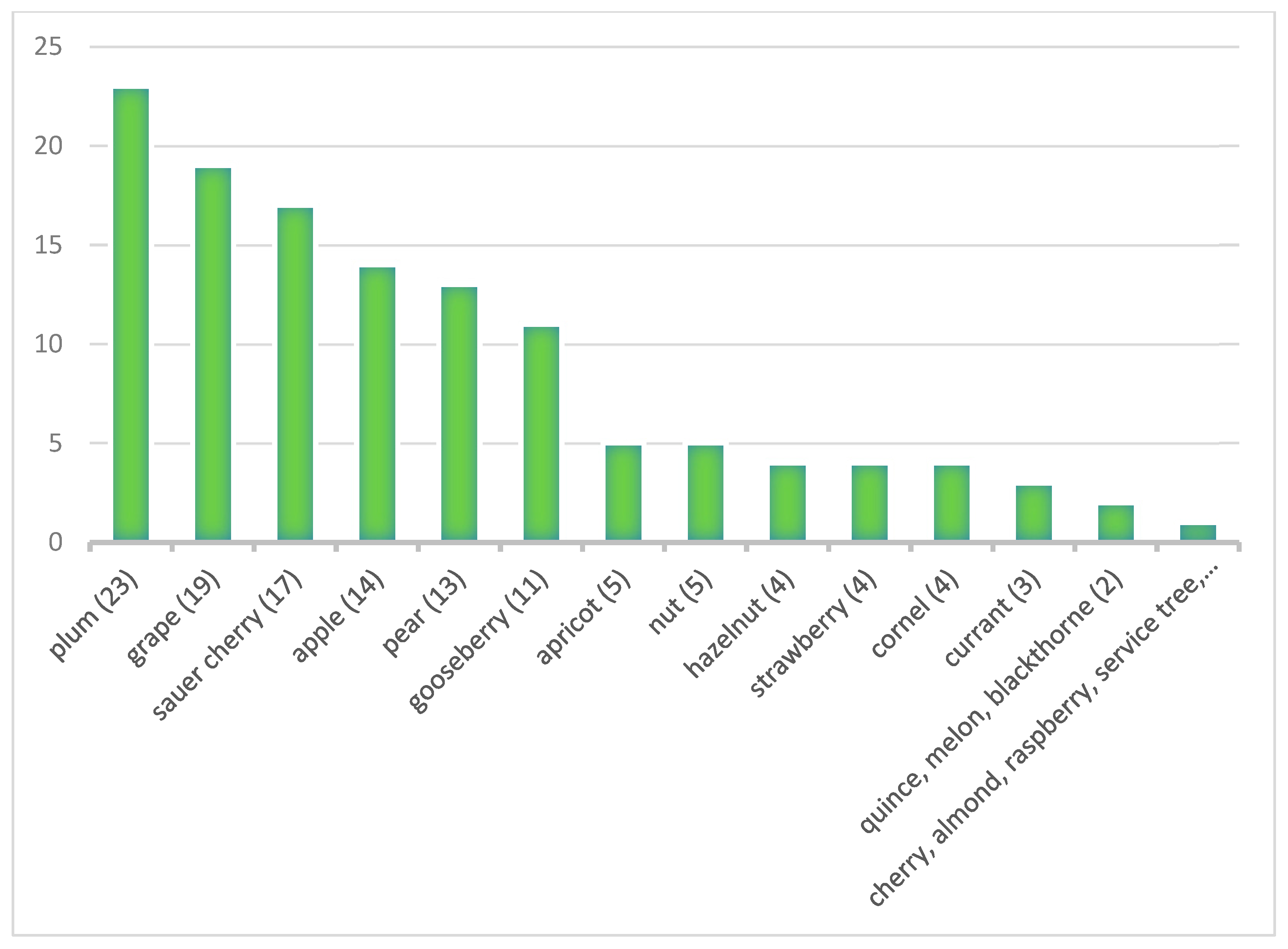

During the research, the researchers found references to a total of 21 different fruit varieties in 39 residence gardens. The fruit varieties mentioned in contemporary inventariums and their frequency are shown in Figure 4 and Table 1 for each location. These show that the most popular fruits are plums (mentioned in 23 locations), grapes (19 locations), and sour cherries (17 locations). According to records, the rarest fruits are rowan, quince, cherry, almond, and raspberry. At the same time, Mediterranean plants are also included in the inventarium at two locations: lemon in Uzdiszentpéter and olive tree in Fogaras.

Table 1. List of residential gardens with fruit gardens with a specification of the used fruit varieties (Source: prepared by the Authors, based on [2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28]).

| No | Location | Data (Year) | Apple | Apricot | Sorb | Quince | Lemon | Melon | Nut | Strawberry | Gooseberry | Cherry | Blackthorne | Pear | Almond | Raspberry | Sauercherry | Hazelnut | Oil Tree | Cornel | Plum | Grape | Currant |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Kisbarcsa | 1624 | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | Fogaras | 1632 | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| 3 | Siménfalva | 1636 | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | Tasnád | 1644 | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||||

| 5 | Nagyteremi | 1647 | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 6 | Királyfalva | 1647 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 7 | Meggykerék | 1647 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 8 | Drassó | 1647 | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 9 | Marosvécs | 1648 | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| 10 | Komána | 1648 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||

| 11 | Görgény | 1652 | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||

| 12 | Gerend | 1652 | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||||

| 13 | Búzábocsárd | 1658 | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 14 | Mezőszengyel | 1656 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 15 | Szurdok | 1657 | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 16 | Bethlen | 1661 | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||

| 17 | Mezőbodon | 1679 | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| 18 | Uzdiszentpéter | 1679 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||

| 19 | Nagysajó | 1681 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||

| 20 | Oprakercisóra | 1683 | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 21 | Csíkkozmás | 1688 | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| 22 | Nagybún | 1692 | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||||

| 23 | Borberek | 1694 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||

| 24 | Kővár | 1694 | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 25 | Vajdahunyad | 1695 | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 26 | Szentbenedek | 1696 | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| 27 | Egeres | 1699 | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| 28 | Zentelke | 1715 | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 29 | Grid | 1716 | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||

| 30 | Mezőörményes | 1721 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||

| 31 | Koronka | 1724 | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| 32 | Marosszentkirály | 1725 | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||

| 33 | Aranykút | 1728 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||

| 34 | Bonchida | 1736 | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||||

| 35 | Gernyeszeg | 1751 | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| 36 | Branyicska | 1757 | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||||

| 37 | Szilágycsehi | 17. c. | x | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 38 | Gyulafehérvár | 17. c. | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||

| 39 | Ebesfalva | 17. c. | x | x | |||||||||||||||||||

| TOTAL Number | 14 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 11 | 1 | 2 | 13 | 1 | 1 | 17 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 23 | 19 | 3 | ||

References

- Szikra, É.; Egy, X.V. századi palotakert újjászületése (Mátyás király visegrádi kertjei) . Műemlékvédelem 2003, 3, 186–192.

- Margit, B.N. Várak, Kastélyok, Udvarházak, Ahogy a Régiek Látták; Kriterion Kiadó: Bukarest, Romania, 1973.

- Nagy, M.B. Stílusok, Művek, Mesterek; Kriterion Kiadó: Bukarest, Romania, 1977.

- Balogh, J. A Késő-Renaissance és a Kora-Barokk Művészet; Révai: Budapest, Hungary, 1940.

- Balogh, J. Az Erdélyi Renaissance. 1. köt., 1460–1541; Erdélyi Tudományos Intézet: Kolozsvár, Romania, 1943.

- Balogh, J. Kolozsvári reneszánsz láda 1776-tól. In Emlékkönyv Kelemen Lajos Születésének Nyolcvanadik Évfordulójára; Bodor, A., Ed.; Tudományos Könyvkiadó: Bukarest, Romania, 1957; pp. 9–23.

- Balogh, J. Kolozsvári Kőfaragó Műhelyek, XVI. Század; MTA Művészettörténeti Kutató Csoport: Budapest, Hungary, 1985; pp. 9–23.

- Balogh, J. A Művészet Mátyás Király Udvarában; Akadémiai Kiadó: Budapest, Hungary, 1966.

- Zsigmond, J. A Gyalui Vártartomány Urbáriumai; Erdélyi Tudományos Intézet: Kolozsvár, Romania, 1944.

- Zsigmond, J. Adatok a Dézsma Fejedelemségkori Adminisztrációjához; Erdélyi-Múzeum-Egyesület: Kolozsvár, Romania, 1945.

- Zsigmond, J. Az Otthon és Művészete a XVI–XVII. Századi Kolozsváron: Szempontok Reneszánszkori Művelődésünk Kutatásához; Tud. Kiadó: Kolozsvár, Romania, 1958.

- Zsigmond, J. Erdélyi Okmánytár. Oklevelek, Levelek és Más Írásos Emlékek Erdély Történetéhez I.: 1023–1300; Akad. K.: Budapest, Hungary, 1997.

- Archival source: Arhivele Academiei Romane, Mikó_Rédey család levéltára, dobozolt anyag, 179–197 lap (Nagysajó, 1681) .

- Archival source: Arhivele Academiei Ro.mane, Jósika család hitbizományi levéltára, Fasc. I, Nr. 14. (Csíkkozmás, 1688) .

- Archival source: Arhivele Academiei Romane, Bánffy család levéltára, Fasc 28, Nr.2. (Mezőörményes, 1721) .

- Szádeczky, L. (Ed.) I. Apafi Mihály Fejedelem Udvartartása, Bornemisza Anna Gazdasági Naplói 1667–1690; Magyar Tudományos Akadémia Könyvkiadóhivatala: Budapest, Hungary, 1911; Volume 1.

- Tüdős, S.K. Egy székely nemesasszony élete és személyisége Apafi korában. Lázár Erzsébet Kálnoky Sámuelné. In Erdély és Patak Fejedelemasszonya, Lorántffy Zsuzsanna I–II; Tamás, E., Ed.; Rákóczi Múzeum: Sárospatak, Hungary, 2000; Volume 1, pp. 93–106.

- Nagy-Tóth, F.; Fodorpataki, L. Tündérkertész Lorántffy Zsuzsanna kertészeti jelentősége. In Erdély és Patak Fejedelemasszonya, Lorántffy Zsuzsanna I–II; Tamás, E., Ed.; Rákóczi Múzeum: Sárospatak, Hungary, 2000; Volume 2, pp. 123–140.

- Makkai, L. Rákóczi György Birtokainak Gazdasági Iratai (1631–1648); Akadémiai Kiadó: Budapest, Hungary, 1954; Available online: http://real-eod.mtak.hu/id/eprint/14013 (accessed on 9 February 2023).

- Bornemisza Anna Gazdasági Naplója. , 1667–1672.—243 f. 117. Biblioteca Digitala BCU Cluj. Available online: http://dspace.bcucluj.ro/handle/123456789/24983 (accessed on 29 March 2023).

- Bornemisza Anna Gazdasági Naplója. , 1667–1672.—243 f. 345. Biblioteca Digitala BCU Cluj. Available online: http://dspace.bcucluj.ro/handle/123456789/24983 (accessed on 29 March 2023).

- Archival source: “Inventarium”, melyet Kisfaludi András a gyulafehérvári káptalan requisitora és a kancellária officiálisa Horváth Boldizsár készítettek. (Összeírás: Vár és berendezése, gazdasági épületek, majorság igen részletes leltára, állatok, szántó, rét, kert, halastó, kocsma). Az erdélyi fejedelmi fiskus javai. Fogaras váruradalma. (Fogaras) HU MNL OL E 156—A.—Fasc. 014.—No. 039. 23.

- Archival source: “Urbarium”, melyet a gyulafehérvári káptalan officiálisa készített. (Subditusok neve, állataik, census, szolgálatuk, allódiális javak részletezve.) Connumeratio. Az erdélyi fiskus java. Fogaras váruradalma (Komána, Porumbák) HU MNL OL E 156—A.—Fasc. 014.—No. 038.

- Archival source: Arhivele Nationale Romane, Sepsiszentgyörgy. Fond 64, fasc. I. (Olasztelek, 1730) .

- Archival source: Magyar Tudományos Akadémia Levéltára Kemény család csekelaki levéltára, 1646, DD, Nr. 102 .

- Archival source: Magyar Tudományos Akadémia Levéltára Jósika család hitbizományi levéltára, limbus. 1736. Fasc. XXXV, Nr. 35.). 1726 (Fasc. 10, Nr. 1.). 1756 (Fasc. 70, Nr. 2.). 1761 (Fasc. 70, Nr. 30.). (Branyicska). .

- Archival source: Magyar Tudományos Akadémia Levéltára Bánffy család levéltára, Fasc. 1, Nr. 42. 1715 (Fasc. XLIII/15.). 1717 (Fasc. 1b, Nr. 41.). 1774 (Fasc. XXXII, Nr. 5.). 1780 (Fasc. 1, Nr. 44.). 1794 (Fasc. 32, Nr. 15.) .

- Archival source: Magyar Tudományos Akadémia Levéltára Bánffy család levéltára, 1638 (Fasc. 28, Nr. 1.). 1751 (AkadLt. A Bánffy család levéltára, Fasc. 28, Nr. 4.). (Mezőörményes) .

- Archival source: Mappa della Transilvania e Provintie contique nella quales Hadtörténeti Intézet és Múzeum, B IX a 487/15 , B IX a, B IX Ausztria–Magyarország, B I–XV. Európa.

More

Information

Subjects:

Green & Sustainable Science & Technology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

697

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

25 May 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No