Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Rosa Divella | -- | 1665 | 2023-04-04 10:29:36 | | | |

| 2 | Dean Liu | Meta information modification | 1665 | 2023-04-06 03:39:47 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Divella, R.; Marino, G.; Infusino, S.; Lanotte, L.; Gadaleta-Caldarola, G.; Gadaleta-Caldarola, G. Physical Activity and Mediterranean Diet in Cancer. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/42770 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Divella R, Marino G, Infusino S, Lanotte L, Gadaleta-Caldarola G, Gadaleta-Caldarola G. Physical Activity and Mediterranean Diet in Cancer. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/42770. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Divella, Rosa, Graziella Marino, Stefania Infusino, Laura Lanotte, Gaia Gadaleta-Caldarola, Gennaro Gadaleta-Caldarola. "Physical Activity and Mediterranean Diet in Cancer" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/42770 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Divella, R., Marino, G., Infusino, S., Lanotte, L., Gadaleta-Caldarola, G., & Gadaleta-Caldarola, G. (2023, April 04). Physical Activity and Mediterranean Diet in Cancer. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/42770

Divella, Rosa, et al. "Physical Activity and Mediterranean Diet in Cancer." Encyclopedia. Web. 04 April, 2023.

Copy Citation

A healthy diet and an active lifestyle are both effective ways to prevent, manage, and treat many diseases, including cancer. A healthy, well-balanced diet not only ensures that the body gets the right amount of nutrients to meet its needs, but it also lets the body get substances that protect against and/or prevent certain diseases. It is now clear that obesity is linked to long-term diseases such as heart disease, diabetes, and cancer.

lifestyle

cancer

nutrition

1. Introduction

Approximately 30–35% of all malignancies are attributed to so-called lifestyle factors, which include an imbalanced diet, being overweight or obese, abusing alcohol, and inactivity [1]. Obesity, defined as abnormal excess accumulation of fat in adipose tissue, causes chronic low-grade inflammation. It is associated with a high risk of developing the four main types of non-communicable diseases (NCDs), namely, type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease, and several types of cancer [2][3]. In tumors of the breast, colon, liver, and prostate, obesity is generally a predictor of poor clinical outcomes. Consequently, diet, viewed as the totality of eating habits, is a significant environmental component capable of regulating neoplastic risk either as a protective factor or as a risk factor, depending on the quality, amount, and frequency of intake of the foods that comprise it [4]. The relationship between nutrition and the immune system is crucial to both sustaining health and causing illness. When the immune system is hyperactive as a result of an unhealthy lifestyle and an imbalanced diet, a low-grade chronic inflammatory state is induced, which increases the risk of developing chronic degenerative illnesses and cancers [5][6]. Nutrition has a dual nature because it can be either a weapon of prevention and therapy or a cause of pathological events if it is primarily composed of pro-inflammatory foods consumed on a regular basis. Diets, such as the traditional Mediterranean diet (MD), and regular physical exercise are effective methods for preventing overweight, obesity, and NCDs, as well as reducing visceral fat and, as a result, the generation of pro-inflammatory cytokines and hormonal imbalances [7][8]. Moreover, the UNESCO in 2010 officially defined the MD as a cultural heritage of humanity, exalting conviviality, sensory stimulation, socialization, biodiversity, and seasonality, aspects that can reinforce the MD’s beneficial effects on wellbeing, quality of life, and healthy physical activity. Furthermore, a balanced diet is now regarded as a very effective tool for the prevention and reduction of mortality and the recurrence of oncological illnesses [9][10]. These intrinsic characteristics of the Mediterranean diet allow us to place it in a really healthy lifestyle, which is reflected in the culinary and working traditions (fishing and sheep farming) of the Mediterranean people, which require intense physical effort (far from a sedentary life) and, therefore, high energy consumption.

Physical exercise benefits cancer patients, including those receiving oncological treatments such as chemotherapy, hormone therapy, radiation, and surgery, as well as those in the rehabilitation phase and long-term survivors [11]. Physical exercise is now shown to be safe for cancer patients and must be included in treatment regimens, even though it must be tailored to the subject being treated, the kind of pathology, comorbidities, physical conditions, and effort tolerance [9]. Physical exercise, when combined with a balanced diet and a proper lifestyle (no smoking or drinking), leads to a prolongation of the expected lifespan and a decrease in the risk of chronic degenerative illnesses and tumors, which are statistically common in the adult population [12].

2. The Mediterranean Diet (MD)

Thanks to its unusual preventative effects, the MD has attracted the attention of scientists throughout the world. The Mediterranean diet constitutes a food model that characterizes not only a lifestyle but also a culture and has been indicated as a hub for improving health, quality of life, and life span. Numerous studies have highlighted the positive correlation between MD and longevity; individuals who adhere to a nutritional style such as this have a longer life expectancy [13][14]. Moreover, the Mediterranean diet prevents many metabolic, cardiovascular, and neurodegenerative diseases; insulin resistance; and different types of cancer [15][16]. Today, cancer represents the second leading cause of death in the world, immediately after cardiovascular diseases, but its onset curve has lowered in parallel with other chronic degenerative diseases, such as diabetes and obesity. In this context, diet plays a very important role. Epidemiological and clinical studies support the association between nutrition and the development or progression of different cancer malignancies such as colon, breast, prostate, and other cancers, defining these tumors as diet-associated cancers [17][18]. If followed correctly, it may help people avoid the chronic inflammation that results from being overweight, developing metabolic syndrome, and gaining excess weight due to a poor diet. In general, the Mediterranean diet is full of healthy nutrients, including antioxidants, anti-inflammatories, and insulin sensitizers [19][20]. Within several months of its implementation, it has been linked to less inflammation and has been shown to reduce inflammatory cytokines (IL-6 and TNF-alpha) and the C-reactive protein and to enhance anti-inflammatory IL-10 [21][22]. In addition to lowering insulin levels and correcting hepatic steatosis, the MD has been shown to reverse the metabolic syndrome in a significant number of patients. It is a healthy routine that has been shown to reduce cancer risk [23][24]. This is because eating these foods together helps prevent DNA damage, cell proliferation, and the survival of cancer cells by lowering oxidative and inflammatory processes inside the body [25]. Furthermore, in the DIMENU study (Dieta Mediterranea and Nuoto), according to the data reported in the literature, serum from adolescents with high adherence to the Mediterranean diet reduced inflammation in human macrophage in vitro models, suggesting that it could have a positive impact on the prevention of chronic diseases, including cancers in adulthood [26].

3. Role of an Anti-Inflammatory and Calorie-Restricted Diet in Cancer Prevention

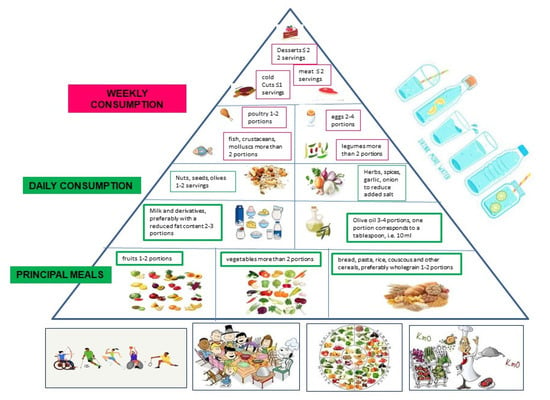

The typical Mediterranean diet can help avoid cancer. To achieve this objective, it is recommended to follow the diet following the suggestions below and illustrated in the model of the Mediterranean diet pyramid illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The typical Mediterranean diet and lifestyle raccomandations to follow: Mediterranean Lifestyle.

The Typical Mediterranean Diet Recommendations to Follow

- (1)

-

Consume whole grains every day, three portions a day of vegetables, two portions a day of fruit, and legumes 3–4 times a week.

- (2)

-

Limit the consumption of red meat, avoid processed meats such as preserved meats, cold cuts, and frankfurters.

- (3)

-

Stay away from items high on the glycemic index, such as white bread, white rice, and simple sweets. Dinner carbs are acidifying and may raise blood sugar and insulin levels, so it is best to avoid them.

- (4)

-

Fruit is best eaten on an empty stomach, either first thing in the morning or late in the afternoon and never toward the conclusion of a meal, especially one that is high in carbs. Do not eat fruit salad since it contains ingredients with wildly varying pH levels, many of which might lead to stomach and bowel issues.

- (5)

-

Foods high in acidity and polyamines should be avoided (vegetables of the nightshade family, oranges, tangerines, mandarin oranges).

- (6)

-

Stay away from packaged foods with hydrogenated polyunsaturated fatty acids (trans), which cause high cholesterol and inflammation throughout the body, which damages cells. Trans fats can be found in bakery products such as industrial bread, cookies, and pastries, as well as in ready-to-eat meals and French fries.

- (7)

-

Food supplements should not be taken unless they have been properly tested in clinical trials.

- (8)

-

Observe a moderate calorie restriction while making sure that all essential nutrients are in the diet. This is to make sure that the nutritional status is not affected (for example 1–2 days a week).

- (9)

-

Weight should be managed in a healthy way; one should “stay trim” and monitor one’s waist circumference (waist size), which should be no more than 80–88 cm in women and 94–102 cm in males.

- (10)

-

Even more so as you get older, it is important to get your body moving every day; try going for a brisk 30 min walk, walking 10,000 steps, or spending an hour at the gym.

Numerous studies suggest that calorie restriction decreases plasma insulin, glucose levels, sex hormones, and inflammatory cytokines; increases detoxifying enzymes; decreases oxidative stress; and increases adiponectin, an anti-inflammatory protein produced by adipocytes [27][28][29]. When the diet contains all the required nutrients, 25–30% less calories in the diet lengthens animal life and minimizes the occurrence of cancers [30]. In fact, it has been shown that calorie restriction stimulates the AMPK (AMP-activated protein kinase) protein, which decreases the production of mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin), one of the major oncogenes and regulators of cell growth and proliferation [31][32]. When caloric restriction is accompanied by a drop in animal protein, plasma levels of IGF-1 decline, which, in conjunction with insulin, activates the PI3K–Akt–mTORC signaling pathway [33]. As an alternative to mitochondrial respiration, the latter may stimulate cell growth and aerobic glycolysis, which constitutes the primary energy source of cancer cells. Aerobic glycolysis generates lactic acid and acidifies the milieu in which tumors thrive; the acidity increases tumor dissemination by boosting angiogenesis through VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor) [34]. It has been shown that even brief periods of fasting (a couple of days a week) lower blood sugar, insulin, and IGF-1 levels and enhance the efficacy of oncological therapies [35][36]. By blocking mTOR, calorie restriction is in fact able to limit cancer cells’ DNA repair capabilities. In the days before chemotherapy, calorie restriction might be prescribed to cancer patients. In conclusion, the key points of physical exercise and a healthy Mediterranean diet are given below:

-

Modulates insulin levels, reduces insulin resistance and insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1).

-

Fights against weight gain and obesity.

-

Decreases the production of inflammatory adipokines and leptin (mitogenic factor) while increasing the production of adiponectin (pro-apoptotic factor) by adipocytes with anti-inflammatory and antitumor action.

-

Reduces plasma levels of estrogens, which are involved in the growth of breast and endometrial cancer cells.

-

Contributes to the anti-inflammatory action with the muscular release of anti-inflammatory myokines whose protective effect in many tumors has been demonstrated.

-

Increases intestinal motility, thereby reducing the contact time of the intestinal mucosa with carcinogenic compounds.

-

Modifies the composition and metabolic profile of the microbiota, exerting a protective action in inflammatory bowel diseases.

References

- Ng, R.; Sutradhar, R.; Yao, Z.; Wodchis, W.P.; Rosella, L.C. Smoking, drinking, diet and physical activity-modifiable lifestyle risk factors and their associations with age to first chronic disease. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2020, 49, 113–130.

- Marshall, K.; Beaden, P.; Durrani, H.; Tang, K.; Mogilevskii, R.; Bhutta, Z. The role of the private sector in noncommunicable disease prevention and management in low- and middle-income countries: A series of systematic reviews and thematic syntheses. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2023, 18, 2156099.

- Cheah, Y.K.; Lim, K.K.; Ismail, H.; Mohd Yusoff, M.F.; Kee, C.C. Can the association between hypertension and physical activity be moderated by age? J. Taibah Univ. Med. Sci. 2023, 18, 844–854.

- Gherasim, A.; Arhire, L.I.; Niță, O.; Popa, A.D.; Graur, M.; Mihalache, L. The relationship between lifestyle components and dietary patterns. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2020, 79, 311–323.

- Soldati, L.; Di Renzo, L.; Jirillo, E.; Ascierto, P.A.; Marincola, F.M.; De Lorenzo, A. The influence of diet on anti-cancer immune responsiveness. J. Transl. Med. 2018, 16, 75.

- Childs, C.E.; Calder, P.C.; Miles, E.A. Diet and Immune Function. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1933.

- Calcaterra, V.; Verduci, E.; Vandoni, M.; Rossi, V.; Fiore, G.; Massini, G.; Berardo, C.; Gatti, A.; Baldassarre, P.; Bianchi, A.; et al. The Effect of Healthy Lifestyle Strategies on the Management of Insulin Resistance in Children and Adolescents with Obesity: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4692.

- Sood, S.; Feehan, J.; Itsiopoulos, C.; Wilson, K.; Plebanski, M.; Scott, D.; Hebert, J.R.; Shivappa, N.; Mousa, A.; George, E.S.; et al. Higher Adherence to a Mediterranean Diet Is Associated with Improved Insulin Sensitivity and Selected Markers of Inflammation in Individuals Who Are Overweight and Obese without Diabetes. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4437.

- United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. Available online: http://www.unesco.org/culture/ich/index.php (accessed on 8 October 2015).

- Dominguez, L.J.; Veronese, N.; Di Bella, G.; Cusumano, C.; Parisi, A.; Tagliaferri, F.; Ciriminna, S.; Barbagallo, M. Mediterranean diet in the management and prevention of obesity. Exp. Gerontol. 2023, 174, 112121.

- Iolascon, G.; Di Pietro, G.; Gimigliano, F.; Mauro, G.L.; Moretti, A.; Giamattei, M.T.; Ortolani, S.; Tarantino, U.; Brandi, M.L. Physical exercise and sarcopenia in older people: Position paper of the Italian Society of Orthopaedics and Medicine (OrtoMed). Clin. Cases Miner. Bone Metab. 2014, 11, 215–221.

- Cerqueira, É.; Marinho, D.A.; Neiva, H.P.; Lourenço, O. Inflammatory Effects of High and Moderate Intensity Exercise-A Systematic Review. Front. Physiol. 2020, 10, 1550.

- Turati, F.; Dalmartello, M.; Bravi, F.; Serraino, D.; Augustin, L.; Giacosa, A.; Negri, E.; Levi, F.; La Vecchia, C. Adherence to the World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research Recommendations and the Risk of Breast Cancer. Nutrients 2020, 12, 607.

- Ribeiro, G.; Ferri, A.; Clarke, G.; Cryan, J.F. Diet and the microbiota–gut–brain-axis: A primer for clinical nutrition. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care. 2022, 25, 443–450.

- Merra, G.; Noce, A.; Marrone, G.; Cintoni, M.; Tarsitano, M.G.; Capacci, A.; De Lorenzo, A. Influence of Mediterranean Diet on Human Gut Microbiota. Nutrients 2020, 13, 7.

- Itsiopoulos, C.; Mayr, H.L.; Thomas, C.J. The anti-inflammatory effects of a Mediterranean diet: A review. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care. 2022, 25, 415–422.

- Romagnolo, D.F.; Selmin, O.I. Mediterranean Diet and Prevention of Chronic Diseases. Nutr. Today 2017, 52, 208–222.

- Dominguez, L.J.; Di Bella, G.; Veronese, N.; Barbagallo, M. Impact of Mediterranean Diet on Chronic Non-Communicable Diseases and Longevity. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2028.

- Muscogiuri, G.; Verde, L.; Sulu, C.; Katsiki, N.; Hassapidou, M.; Frias-Toral, E.; Cucalón, G.; Pazderska, A.; Yumuk, V.D.; Colao, A.; et al. Mediterranean Diet and Obesity-related Disorders: What is the Evidence? Curr. Obes. Rep. 2022, 11, 287–304.

- Janssen, J.A. The Impact of Westernization on the Insulin/IGF-I Signaling Pathway and the Metabolic Syndrome: It Is Time for Change. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4551.

- Lécuyer, L.; Laouali, N.; Dossus, L.; Shivappa, N.; Hébert, J.R.; Agudo, A.; Tjonneland, A.; Halkjaer, J.; Overvad, K.; Katzke, V.A.; et al. Inflammatory potential of the diet and association with risk of differentiated thyroid cancer in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) cohort. Eur. J. Nutr. 2022, 61, 3625–3635.

- Hayati, Z.; Montazeri, V.; Shivappa, N.; Hebert, J.R.; Pirouzpanah, S. The association between the inflammatory potential of diet and the risk of histopathological and molecular subtypes of breast cancer in northwestern Iran: Results from the Breast Cancer Risk and Lifestyle study. Cancer 2022, 128, 2298–2312.

- Bifulco, M.; Pisanti, S. The mystery of longevity in Cilento: A mix of a good dose of genetic predisposition and a balanced diet based on the Mediterranean model. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 71, 1020–1021.

- Naureen, Z.; Dhuli, K.; Donato, K.; Aquilanti, B.; Velluti, V.; Matera, G.; Iaconelli, A.; Bertelli, M. Foods of the Mediterranean diet: Tomato, olives, chili pepper, wheat flour and wheat germ. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2022, 63 (Suppl. 3), E4–E11.

- Naureen, Z.; Bonetti, G.; Medori, M.C.; Aquilanti, B.; Velluti, V.; Matera, G.; Iaconelli, A.; Bertelli, M. Foods of the Mediterranean diet: Garlic and Mediterranean legumes. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2022, 63 (Suppl. 3), E12–E20.

- Koelman, L.; Egea Rodrigues, C.; Aleksandrova, K. Effects of Dietary Patterns on Biomarkers of Inflammation and Immune Responses: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Adv. Nutr. 2022, 13, 101–115.

- Millar, S.R.; Navarro, P.; Harrington, J.M.; Shivappa, N.; Hébert, J.R.; Perry, I.J.; Phillips, C.M. Dietary score associations with markers of chronic low-grade inflammation: A cross-sectional comparative analysis of a middle- to older-aged population. Eur. J. Nutr. 2022, 61, 3377–3390.

- Ryan, M.C.; Itsiopoulos, C.; Thodis, T.; Ward, G.; Trost, N.; Hofferberth, S.; O’Dea, K.; Desmond, P.V.; Johnson, N.A.; Wilson, A.M. The Mediterranean diet improves hepatic steatosis and insulin sensitivity in individuals with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Hepatol. 2013, 59, 138–143.

- Mirabelli, M.; Chiefari, E.; Arcidiacono, B.; Corigliano, D.M.; Brunetti, F.S.; Maggisano, V.; Russo, D.; Foti, D.P.; Brunetti, A. Mediterranean Diet Nutrients to Turn the Tide against Insulin Resistance and Related Diseases. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1066.

- Augimeri, G.; Galluccio, A.; Caparello, G.; Avolio, E.; La Russa, D.; De Rose, D.; Morelli, C.; Barone, I.; Catalano, S.; Andò, S.; et al. Potential Antioxidant and An-ti-Inflammatory Properties of Serum from Healthy Adolescents with Optimal Mediterra-nean Diet Adherence: Findings from DIMENU Cross-Sectional Study. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1172.

- Mentella, M.C.; Scaldaferri, F.; Ricci, C.; Gasbarrini, A.; Miggiano, G.A.D. Cancer and Mediterranean Diet: A Review. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2059.

- La Russa, D.; Marrone, A.; Mandalà, M.; Macirella, R.; Pellegrino, D. Antioxidant/Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Caloric Restriction in an Aged and Obese Rat Model: The Role of Adiponectin. Biomedicines 2020, 8, 532.

- Martin, B.; Mattson, M.P.; Maudsley, S. Caloric restriction and intermittent fasting: Two potential diets for successful brain aging. Ageing Res. Rev. 2006, 5, 332–353.

- Colleluori, G.; Villareal, D.T. Weight strategy in older adults with obesity: Calorie restriction or not? Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2023, 26, 17–22.

- Brandhorst, S.; Longo, V.D. Fasting and Caloric Restriction in Cancer Prevention and Treatment. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2016, 207, 241–266.

- Kopelovich, L.; Fay, J.R.; Sigman, C.C.; Crowell, J.A. The mammalian target of rapamycin pathway as a potential target for cancer chemoprevention. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2007, 16, 1330–1340.

More

Information

Subjects:

Primary Health Care

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

699

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

06 Apr 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No