1. Indoor Sacred Soundscapes

1.1. The Aspect of Sound in the Medieval Serbian Churches

Considering the acoustical problems, it is necessary to keep in mind the basic purpose of the examined space, as well as its end users’ expectations regarding the sonic environment. The Serbian Orthodox Church adopted the Byzantine comprehension of sacred space as an ideal image of the universe in which sound consequently contributed to the overall religious experience. Saint Sava, the first archbishop of the Serbian Orthodox Church and the youngest son of the Grand Prince Stefan Nemanja, referred to the sound of divine service as the very soul of the sacred place

[1]. The divine service, as the most significant religious act, has three main purposes: to spread the Christian faith and lift the faithful’s spirit to God; to facilitate and induce praying, expressed in both spoken pious conversation with God and ecclesiastical chanting; and to induce redemption and the unification of man and God through faith, and a Christian life full of virtues, prayer, and secrets

[2]. In other words, both spoken and chanted word has been important in Orthodox Christian religious practice.

Along with Christian faith, Byzantine chanting tradition was adopted in medieval Serbia. This monophonic

a cappella chant is based on recognizable musical formulas, with a gradual melodic flow and using musical intervals smaller than a semitone

[3]. Each spoken word is given the quality of a song so that the chanting highlights the essence of the lyrics. Saint John of Damascus systematized church chanting in the Octoechos, the church book for chanters that contains eight voices or modes, each “ruling” the divine service for a week. The adoption of the eight modes of the antique music enabled the expression of a variety of feelings in Byzantine chanting in accordance with the liturgical cycle

[4]. The spiritual importance of chanting is also emphasized by medieval hagiographers: Teodosije wrote that while on his deathbed, Stefan Nemanja (later canonized as Saint Simeon) requested to be escorted with monks’ chanting, until finally he looked as if he himself “chanted an angel song with angels”

[5]. The chanting was expected to be acoustically intensified inside a church by blurring and dissolving sound into an immersive acoustic experience, thus enhancing the stimuli of vision and scent

[6].

1.2. Church Acoustics

1.2.1. Monastic Churches

The acoustics of medieval monastic churches have been studied in the last several decades, including the acoustic vessels embedded in the massive walls and the acoustics of the church’s interior space.

Acoustic vessels are found in 15 medieval churches that are now under the jurisdiction of the Serbian Orthodox Church in what today is Serbia. Several of them have been examined theoretically

[7], but only the ones from two churches—in the villages Komarane

[8] and Trg

[9]—have been tested in the laboratory. The resonant frequency of the tested vessels is in the range of a male voice. However, from the archaeoacoustic point of view, it is not only the question of acoustic efficiency that is important but the ideas that lie beneath the building practice of embedding acoustic vessels into church walls

[10]. Therefore, it is necessary to include an analysis of all available vessels from medieval Serbia in order to arrive at a statistically justified conclusion to contribute to the existing body of knowledge on acoustic vessel practices in medieval Europe

[11][12][13], possibly leading to a better understanding of the transmission of this practice between East and West.

Previous acoustic measurements of monastic churches built in medieval Serbia included Lazarica church

[14] and the monastic churches of Ljubostinja Monastery and Naupara Monastery

[15], Manasija Monastery, Ravanica Monastery, and Pavlovac Monastery

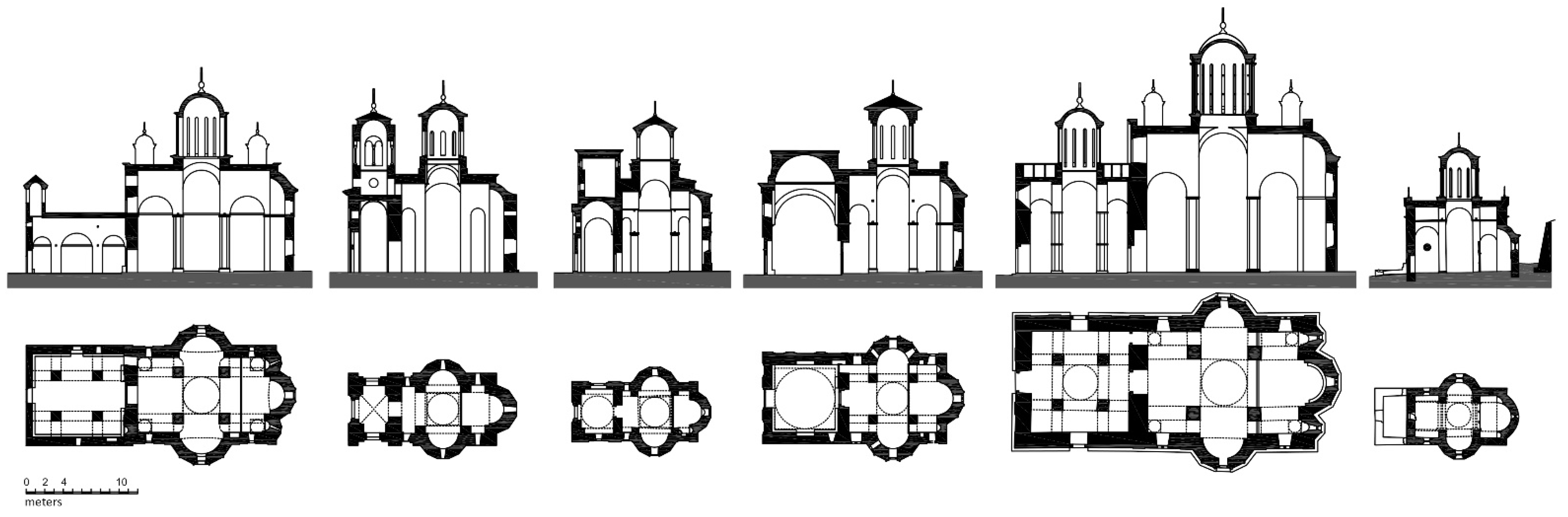

[16]. All these churches were built in the Morava architectural style (1371–1456), which is considered to be the climax of church building in Serbia. They have a triconch plan combined with a developed or compressed inscribed cross, chanting apses on the northern and southern side, and a central dome (

Figure 1). The developed inscribed cross plan has four columns supporting the central dome, which enabled building a larger church, as can be observed in

Figure 1. For the purpose of comparison, Manasija church (

Figure 1, second from the right) has a volume of about 4000 cubic meters, while the smallest one also built in the Morava style is Pavlovac church (

Figure 1, the first one from right), which has a volume of about 400 cubic meters.

Figure 1. Plans and longitudinal sections of the Morava-style medieval churches (range of years of building), from the left to the right: Ravanica (1375–1377), Lazarica (1377–1380), Naupara (1377–1382), Ljubostinja (1381–1388), Manasija (1407–1427), and Pavlovac (1410–1425).

When discussing acoustics, it is important to note the finishing of large surfaces. Medieval monastic churches in Serbia usually have stone floors and fresco painted walls from the floor to the apex of the dome. However, the level of fresco paintings preservation varies from one church to another. Figure 2 shows the case of Ravanica monastic church, in which the upper zone of the wall paintings is significantly damaged and large areas are mortared as a part of conservation works. There are also churches that have no wall paintings at all, such as Lazarica and Pavlovac. The iconostases (the screens separating the naos from the sanctuary apse) are found today made of stone with a height of about 2.5 m (as in medieval times), or made of wood and significantly taller, with a large wooden cross on top. The church furniture is made of wood, and is dominantly located in the apses and under the central dome.

Figure 2. The nave interior of the Ravanica monastic church: view towards the altar (left and middle) and upwards to the central dome (right) (photo: Zorana Đorđević).

Acoustic measurements of impulse responses were carried out for all of the above-mentioned churches using EASERA acoustic software (Version 1.0b (2005), SDA—Software Design Anhert GmbH, Germany). The level of measured background noise in all churches was extremely low, ranging from 21 to 23 dBA, which was expected considering that the locations of the churches are isolated from any external sources of noise, far from urban areas. The only exception is the Lazarica church, which is located in an urban environment, and where the background noise level during measurement was 26 dBA.

Interesting conclusions can be drawn from the comparison of acoustic parameters of churches of different volumes, such as Ljubostinja (circa 1500 m

3) and Naupara (circa 500 m

3). Although Ljubostinja church has a volume three times larger than that of Naupara, differences in the average reverberation times between the two churches are not so pronounced. This can be explained by the fact that Ljubostinja has more wooden surfaces within the naos, which is an additional reason for the even higher average absorption coefficient of the Ljubostinja naos compared with the same area in Naupara. The significantly shorter-than-expected reverberation time in Ljubostinja could be explained by the columns in the naos, which are dominant acoustic diffraction elements. Sound diffraction exerts its own impact on shortening reverberation time due to an overall shortening of the average path distance that sound waves pass. Such acoustical situations increase the possibility of significantly different behavior in sound fields (that can result in the shortening of reverberation time), which cannot be observed simply by comparing only the overall volumes of two or more spaces. The similar reverberation times in both churches’ naos might indicate similar values of acoustic parameters that describe speech intelligibility; however, this is not the case. Namely, Speech Transmission Index (STI) which was derived from the impulse response measurement using EASERA software, has much greater values for Naupara, indicating noticeably higher levels of speech intelligibility for this church. Such a situation can be explained by its smaller interior volume and the reduced path distances that sound waves pass in Naupara, resulting in the greater part of the reflection energy arriving to the listener within the ear’s integration time zone (first 50 ms after the arrival of direct sound). The sound energy that reaches listeners within this time zone is considered as useful in the sense of speech intelligibility. More energy comes to a listener after this period, which is characteristic for Ljubostinja, distracting the speech recognition process and resulting in lesser values in speech intelligibility parameters. It is notable that the best speech intelligibility is under the central dome of the Naupara naos, which is close enough to a listener to provide reflection that improves overall speech intelligibility. Finally, acoustic parameters clearly indicate a significant reduction in speech intelligibility in the case of sound field excitation from the altar. Singing in the altar area behind the iconostasis has a specific role in Orthodox divine service, with the main intention of encouraging a sense of the holy mystery, while the comprehensibility of spoken and sung text is not so important

[15].

In the case of Lazarica church, the STI parameter indicates that intelligibility under the dome highly depends on the position of the sound source. When the excitation signal was from the altar, the STI parameter had a value of 0.491 when measured directly under the dome, and when the excitation was from the chanting apse, the STI for the same receiver position was 0.673. Such a situation can be explained with specific relations between chanting apse and the “under the dome“ position. A person standing under the dome is in front of the chanting apse, having the highest “direct to reflected” sound ratio, which directly impacts speech intelligibility, while there is a physical barrier (iconostasis) between the sound source in the altar and the same receiver position

[14].

In addition to the comparison of acoustic parameters, the subjective assessment of church acoustics provides valuable additional information on the experience of sound in a sacred place. A comparative analysis of acoustic parameters measured in three monastic churches built from masonry—Manasija, Ravanica, and Pavlovac—along with a wooden church in Brzan village was conducted together with a subjective assessment of sound field characteristics with 119 respondents, aged 15 to 61, based on listening to the auralization files of Byzantine chanting and speech. Pavlovac church is perceived as the largest space by 39% of respondents, ahead of the Manasija church, which has a nearly 8-times-larger volume than Pavlovac. Such an unexpected result is due to the acoustic influence of the dome. A listener beneath the dome in Pavlovac church observes acoustic phenomena that are not so audibly conspicuous in higher churches, such as Ravanica and Manasija. The dome directs the sound waves towards its geometric focus, producing a unique play of late delays and consequential changes of the phase differences of the reflected sound waves, finally resulting in a subjective perception of a much larger space than it actually is. The results of acoustic measurements support this as well. The subjective evaluation of speech intelligibility and the STI parameter are matching. They are both inversely proportional to the sizes of the church, so that their values decrease as the volume grows. This is fairly logical situation, since higher amounts of late sound energy coming to the listener, which is a characteristic of larger spaces, is the main reason for decreases in overall speech intelligibility. The results of the subjective evaluation suggest the same: the smallest church (Brzan) is evaluated as “the best”, while the biggest one (Manasija) is seen as having “the worst” speech intelligibility. Additionally, different positions within the same church are characterized by different values of STI parameter. Thus, the speech generated inside the naos, in the case of Ravanica and Manasija, is almost completely incomprehensible in the narthex: most of the respondents (85%) were evaluated as “unsatisfied” in those positions regarding speech intelligibility

[16].

Changes to the original church interior might dramatically affect the experience of sound. For example, the Trg church deviates from the expected values of the reverberation time. The average RT @ 500 Hz for small churches of overall volume similar to the volume of Trg church (around 400 m

3) is around 1.6 s

[17]. However, the average measured values of the T30 parameter in Trg church is 0.60 s at the octave with the central frequency of 500 Hz. This might be due to the presence of wooden furniture but also a thick layer of carpets that authors were not allowed to remove during the acoustic measurements. Such floor carpeting, often justified by the necessary thermal insulation of the church floor, produces a significant deviation from the original acoustic condition of the church. Accordingly, it should be noted that the “original” reverberation time of the church could be even higher than 30% in the higher frequency range but not significant in the lower frequency range

[9].

Additionally, Trg church is a good illustration for an acoustic situation where the Early Decay Time (EDT) parameter has consistently greater values than the T30 parameter in the case of sound excitation from the altar area, while in the case of excitation from the naos, the situation is the opposite. Since EDT correlates with reverberance, or as a perceived reverberation during music play or speech (at least as perceived by the audience), the conclusion is the that overall perceived reverberance inside of the church is greater in the case of chanting from altar, then from the naos. In other words, divine service from the naos position has a tendency toward intimacy due to the nearness of the talker and listener, while the performance from the altar causes difficulty in locating a sound source, thus adding to the sense of mystery of the religious service. The same conclusion can be drawn for most of the other analyzed medieval churches.

1.2.2. Wooden Churches

Wooden churches have been built in Serbia since the medieval times. The earliest recorded mention of log churches in Serbian lands was in the Life of Saint Sava, written in the 14th century. The hagiographer Teodosije wrote that Saint Sava himself encouraged people to build wooden churches whenever needed

[5]. Under the Ottoman rule in Serbia from the 15th to the 19th century, wooden churches retained their simple architecture that allowed them to be easily repaired, disassembled, and transferred to another well-hidden location

[9]. Therefore, the shape of wooden churches did not change from the medieval period. That entitles us, in the scope of this paper, to examine the archaeoacoustic studies of log churches built after medieval period, because turbulent historical circumstances, including uprisings and migrations, left us with log churches not older than the 17th century

[18]. There are about 40 wooden churches preserved today in Serbia. After the First (1804) and the Second (1815) Uprising, and particularly after the official Ottoman recognition of liberty to fully practice Orthodox religion (Hatisherif from 1830), the revitalization of wooden churches began.

Although traditionally called log churches, these buildings are not made of logs but planks. Usually, the oak tree was used, as it is perceived as the most durable building material and provides good sound insulation, rousing feelings of warmth and intimacy

[18]. The architecture is quite simple: single-nave church, consisting of narthex, nave, and apse, and a high roof with eaves. The log church in Brzan village (

Figure 3), built in the first half of 19th century, is particularly interesting as it was equipped with acoustic vessels—ceramic jugs pierced on the bottom. These vessels used to hang from the roof beams, between the roof and the false wooden vault made in a trough shape. As previously mentioned, the acoustic vessels were usually embedded in the masonry walls of medieval churches. The case of Brzan church suggests that the same acoustic practice was applied in wooden architecture as well. The vessels could not be embedded in thin wooden walls but they were hung on the roof beams. When Brzan church was reconstructed in 1960s, mortar was peeled from the interior walls, leaving the visible notches on the wooden planks that are usually made to apply the mortar on the wood. The iconostasis, reaching the ceiling, is also made of wood, and the floor is paved using bricks. Pavlović, who led the reconstruction, wrote that the Brzan church was an acoustical space

[19].

Figure 3. Wooden church in Brzan village: acoustic vessels hanging on the roof construction as found during the reconstruction works in the 1960s (left), church exterior (middle), church interior (right) (photo: Institute for the Protection of Cultural Monuments of Serbia (left), Zorana Đorđević (middle and right)).

2. Outdoor Sacred Soundscapes

2.1. Semantra and Bells

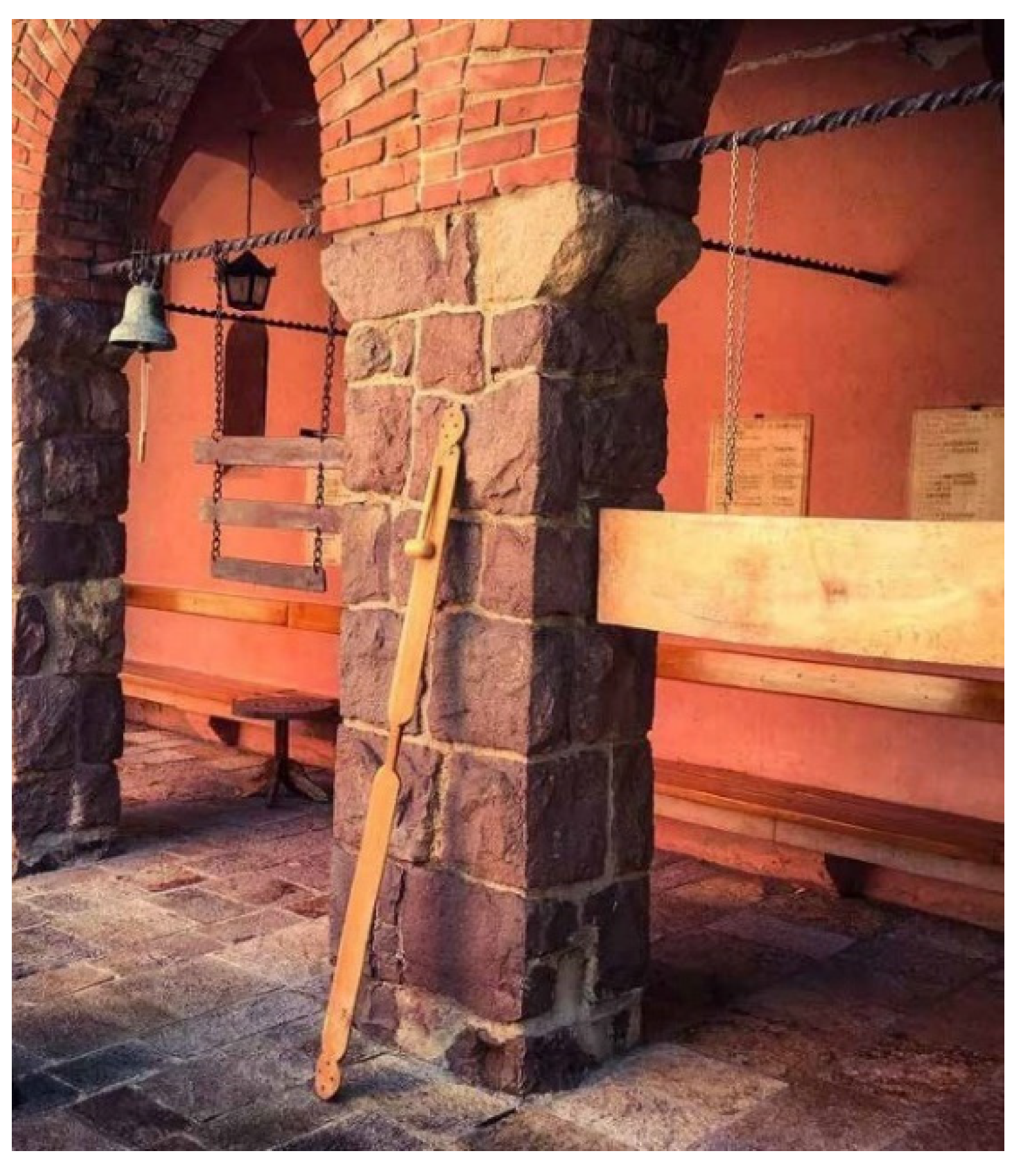

As a traditional instrument in Byzantium, the semantron was adopted in medieval Serbia, known under the names of klepalo and bilo

[20]. The klepalo is a wooden board played with wooden mallets. As

Figure 4 shows, today two types of klepalo—a thin and long plank were found, which is played while a person leans it on their shoulder, or a massive piece of wood hanging on ropes outdoors, usually in the vicinity of the bell tower or church entrance. The bilo is made of bronze plates, which are played with metal hammers while hanging. These three types of semantra were mentioned in the Hilandar Monastery typikon, drafted by Saint Sava in 13th century based on the model of the rule of the Evergetis Monastery in Constantinople. The Hilandar typikon recommends to follow the custom of playing the klepalo and bilo as the first call to divine service, which would then be carried on with bell ringing

[1]. As Rodriguez noted, the Evergetis typikon does not mention bells; however, Saint Sava did mention them in the place which the former refers to the bronze semantron (probably bilo). Arguing further that bell ringing was introduced earlier in medieval Serbia than in Byzantium, Rodriguez pointed out that monuments, such as the endowments of St. Sava’s father, the Grand Prince Stefan Nemanja, such as the monastic church of Saint Nicholas near Kuršumlija (1159–1166) and Đurđevi Stupovi (1166), were both originally built with bell towers. However, while bell ringing did not assume the role of semantra, these percussion instruments were used in conjunction throughout the medieval period, creating an eclectic religious soundscape

[21]. Listing and analyzing the extant bells from medieval Serbia and the wider region, Rodriguez concluded that the pealing of bells had an important role in the local religious soundscape

[22].

Figure 4. The setting of large percussion instruments in the Žiča monastery. From left to right: bell, bilo, klepalce or manual klepalo, klepalo (photo: Zorana Đorđević).

2.2. Litany Procession

Zavetina is a day devoted to a patron saint who protects a village. When a misfortune befalls the village—disease, flood or drought—the villagers would take a vow (

zavet in Serbian) to a saint to celebrate his/her day if in return he/she protects them from the occurring accident. This vow would then pass on to their descendants

[23]. An essential role in the celebration of

Zavetina is placed on

Zapis—a sacred tree with a cross incurved into its bark. This open-air sacred place is a primitive temple where people prayed and made sacrifices. Each village has several sacred trees. The main

Zapis is usually located in a village center, while others are located on a village border, often on private properties

[24].

The most important part of the

Zavetina celebration is a litany procession that starts with a gathering of villagers around the main

Zapis. Then, a priest reads a prayer while villagers carry red flags, crosses, and icons around the sacred tree (

Figure 5). After completing three circles around the

Zapis, the congregation goes around the village borders, visiting all the sacred trees and repeating the same activities of three times circling around each sacred tree while a priest reads a prayer. Then, they would decorate the tree and renew the cross in its bark by recurving it. Consecrating the sacred trees on the village borders, the area inside or along the circle is separated as sacred, leaving as profane everything that remains outside the circle

[25]. The intention of drawing this imagined circle around a village is to protect its inhabitants from various misfortunes. The litany procession was welcome to go across the crop fields to influence the abundant harvest. There was also a belief that litany can contribute to healing people, who were therefore brought onto the procession path

[26]. The litany completes in front of the main

Zapis with the common feast, followed by numerous rite activities, including breaking the festive cake, naming the hosts by the priest, and giving toasts

[25].

Figure 5. Litany on Saint Marco’s Day in the village Lužnice (photo: Marija Dragišić).

2.3. Open-Air Assemblies Related to the State and the Church

Sacred places in medieval Serbia were also used for various gatherings. The most important one was the state assembly—the representative body of medieval Serbia. To discuss the acoustics of open-air sacred places where the medieval assemblies were held, it is essential to know the purpose of these assemblies, the approximate number of participants, and the physical characteristics of the location.

The state assembly gathered the high clergy of the Serbian Orthodox Church, including all the episcopes headed by the archbishop (from the mid-14th century, the patriarch) and an equal number of hegumens or elders of Serbia’s most renowned medieval monasteries. Towards the end of the 14th century, the assembly consisted of the 29 most prominent representatives of the Serbian Orthodox Church—the archbishop, 14 episcopes, and 14 hegumens. In addition to the clergy, the state assembly included the representatives of the state’s civil and military administration, which was, at the most, two or three times the number of the representatives of the church assemblies. If the ruler was absent, he was substituted by his wife. The total number of the assembly participants was limited to about 100 of the most influential persons in the state. The participants were divided into groups and seated around separate tables

[27].

The state assemblies were initiated by the ruler, who chose the time and place, usually in the capital or in a monastery

[28]. On these occasions, rulers were crowned; heirs to the crown were proclaimed; deceased rulers were canonized; church dignitaries, archbishops, and patriarchs were elected; laws were passed; wars were declared; and decisions on important state issues were made. Prior to making the decision, the ruler was obliged to discuss the matter with the most prominent representatives, after which he would announce his decision to the assembly. For example, on the first state assembly in the town of Ras, which was summoned by the progenitor of the Nemanjić dynasty, Stefan Nemanja, both political and religious debate was on the matter of heresy. Later assemblies also show that accordance on state matters often came through long debates, and the assembly could take several days. On the second assembly held in 1196 outside the Saint Peter’s Church in Ras, Nemanja abdicated and appointed his middle son Stefan as heir. To do so, Nemanja needed the support of the assembly, because appointing the younger son as a successor was in breach of tradition and custom laws regarding the rights of the firstborn son and as such needed to be ratified by the state representative body. On this occasion, Nemanja gave a short speech to the assembly. Although the Church did not limit the sovereignty of the ruler, it had the obligation of the ethical supervision but could not deprive the ruler of the throne. On the other hand, the ruler proposed and then the state assembly elected the new archbishop. For that purpose, the assembly would summon at least twice—the first time to elect the archbishop and the second time to attend the church ceremony and the celebration. However, the assembly did not always approve the ruler’s suggestion for the archbishop. During the rule of the king Milutin Nemanjić (1282–1321), the assembly was summoned three times in one year to elect a suitable archbishop

[27].

In addition to the state assemblies, there were also the church assemblies and the church–people’s assemblies. With the foundation of the Serbian autocephalous Archiepiscopy in 1219, Saint Sava became the first archbishop of the Serbian Orthodox Church. He had introduced the church assemblies, which became particularly important after Serbia fell under Ottoman rule in 1459, as they also took over the role of the medieval Serbian state assemblies

[29].

The third type was the church–people’s assembly, which included high clergy, the royal family, and nobility, but also a significant number of poor people. The Church organized them, supported by the ruler, with a clear aim to enhance the reputation of both the Church and the Serbian State. One of the great church–people’s assemblies was organized for the transportation of the relics of Saint Luke the Evangelist in 1453. When the relics, which were believed to have miraculous power, arrived in Serbia from Epirus where they were purchased, they were welcomed by a great solemn procession of the state and church officials, as well as numerous common people. The relics were transported to the capital of Smederevo, where they were then carried through and around the city while the procession attendees chanted church songs. Finally, the relics were placed at the Smederevo Metropolitan Church

[27].