Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ka Shing (William) Cheung | -- | 1301 | 2022-11-19 05:12:48 | | | |

| 2 | Dean Liu | -4 word(s) | 1297 | 2022-11-21 03:17:53 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Cheung, K.; Wong, D. Stress of Moving Homes. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/35323 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Cheung K, Wong D. Stress of Moving Homes. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/35323. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Cheung, Ka-Shing, Daniel Wong. "Stress of Moving Homes" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/35323 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Cheung, K., & Wong, D. (2022, November 19). Stress of Moving Homes. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/35323

Cheung, Ka-Shing and Daniel Wong. "Stress of Moving Homes." Encyclopedia. Web. 19 November, 2022.

Copy Citation

Moving homes has long been considered stressful, but how stressful is it? Researches try to utilise a micro-level individual dataset in the New Zealand Government’s Integrated Data Infrastructure (IDI) to reconstruct the Social Readjustment Rating Scale (SRRS) and thereby measure stress at a whole-of-population level. The effects of residential mobility on people’s mental well-being in the context of their stress-of-moving homes are examined.

residential mobility

well-being

housing tenure

ownership

1. Introduction

Moving homes is a fundamental human experience. While residential mobility can be a mechanism that favourably enables individuals to adjust their housing preferences and well-being, leaving a familiar neighbourhood and relocating to another geographical region often has negative impacts. In moving house and home, people must break their routines and re-establish their social networks [1]. Such a transitory process can also cause much stress and anxiety. Boston Medical Centre suggests that moving house more than two times per year indicates housing instability that increases the probability of adverse health outcomes [2]. Research in psychology further suggests that individuals from households that frequently move from place to place, such as military households, have an increased risk of suicide, substance abuse and even early death [3].

However, at the longitudinal census level, the current understanding of the impact of moving homes is limited. Some researchers, such as Rumbold et al. [4], focus more on the effects of house moves on children. The reason is that longitudinal studies, particularly around the perception of the moving experience and the stress endured before and after changes in residence, often involve large-scale surveys and are very costly to conduct [5]. Other medical measurements of stress using cortisol, sex hormones, and blood pressure could be more objective [6] but are still too expensive to be extended into a census scale. Therefore, an instrument measuring stress objectively without costly sampling is always preferred. Morris et al. suggest that studies need to take account of life events to assess potential confounding or be aware of potential biases [7].

2. Moving Homes is Stressful

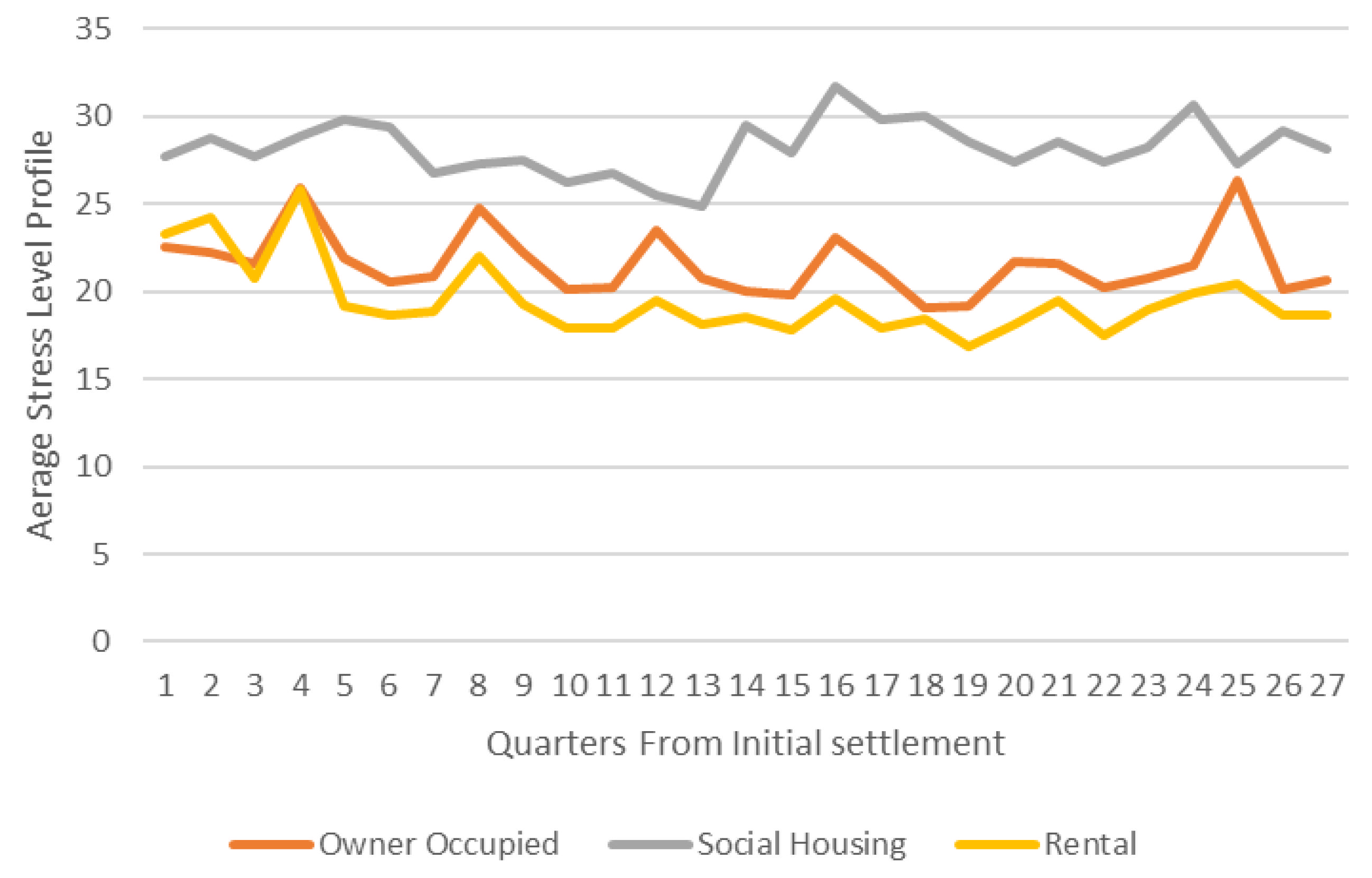

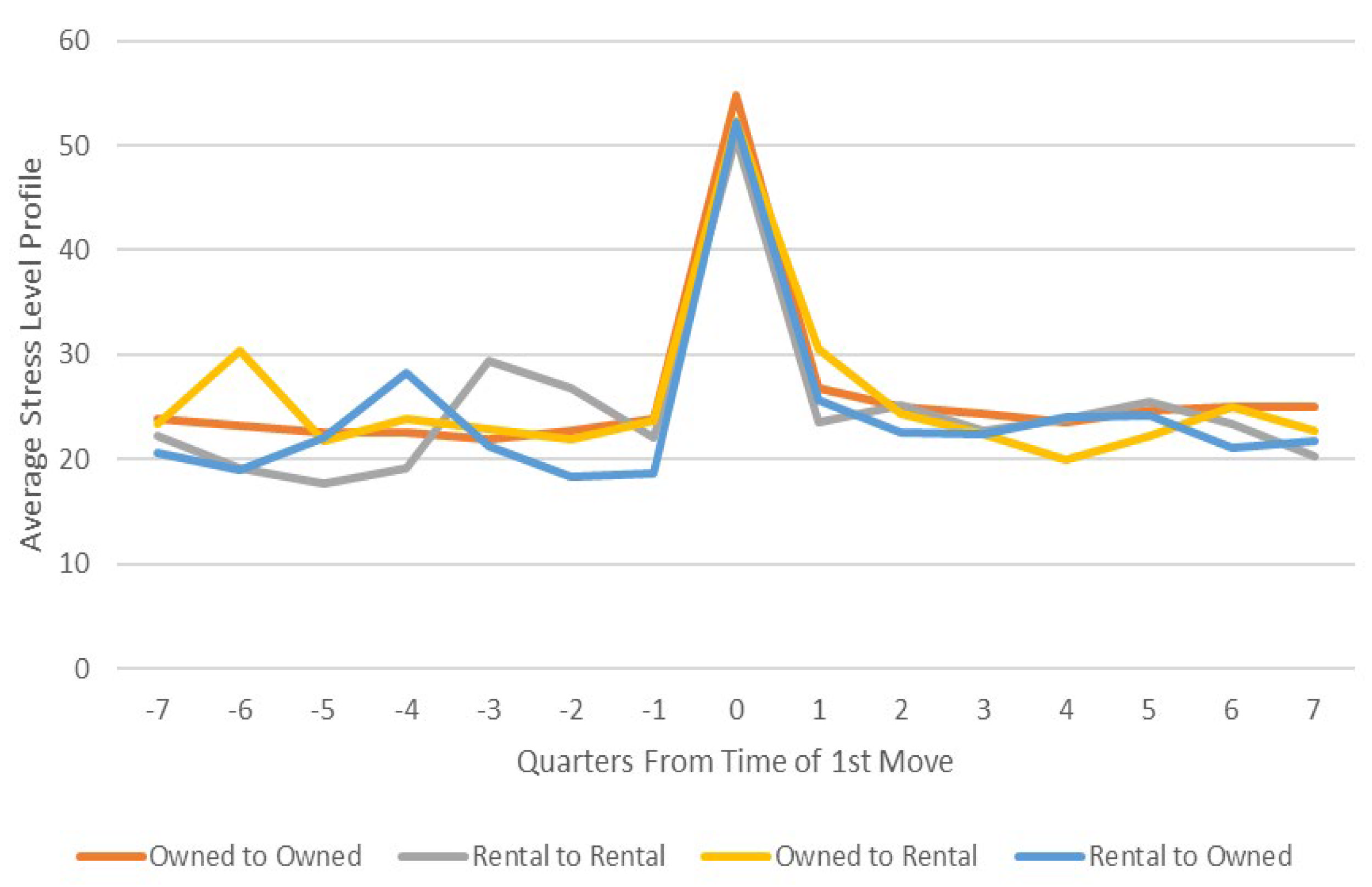

In Figure 1, it is observed that there is a cyclical component to the stress being recorded, visible in both the long-term renters’ and the owners’ segments. This has never been noted in other research articles and warrants further investigation to determine whether this is an instrument’s artefact or an actual socioeconomic phenomenon. Furthermore, when long-term renters in Figure 1 are compared with renters who moved only once, in Figure 3, it is shown that the average baseline stress levels of those who moved were both changing and fluctuating before the move event. This would suggest that there are stresses/stressors creating pressure to move, perhaps from the need for home ownership or housing insecurity.

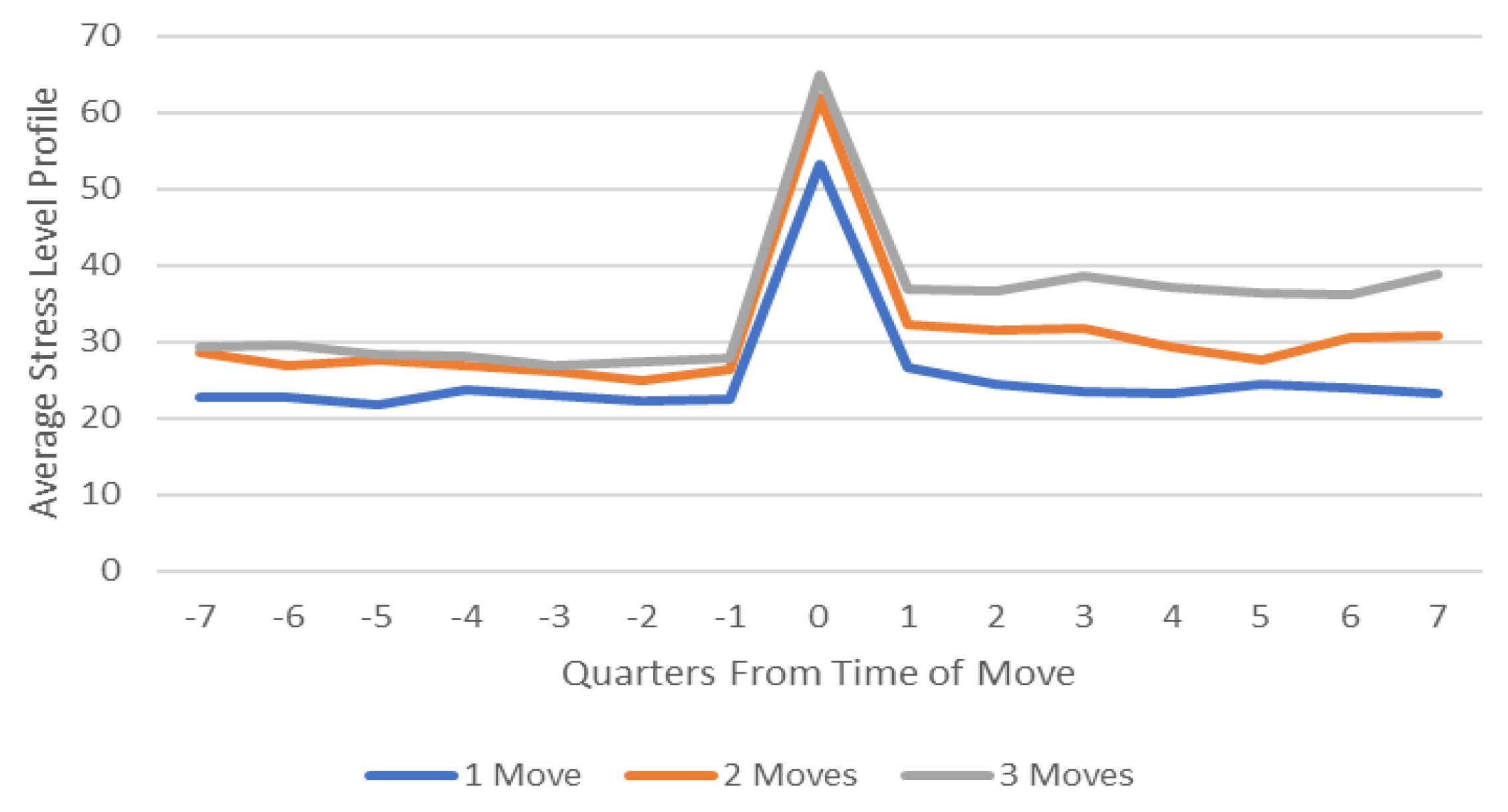

This idea of the stresses/stressors on individuals to move is also reinforced in Figure 2, where it is noted that the baseline stress preceding the movement event. On average, those who moved more frequently were higher than those who moved only once. From the observations above, the data suggest that individuals under high-stress levels, which may be related to housing insecurity, are predisposed to housing movement. While acute stresses seem to result in one-off movements, chronic stresses result in more frequent movement. This also requires further investigation.

Given that this dataset allows being down into the different stresses before and after the move event, other observations can also be made. Table 1 demonstrates the capability of this SRRS instrument in analysing aspects of an individual’s circumstances/stresses, which are traditionally not captured in conventional surveys. Another capability of this instrument is the ability to dissect households’ socioeconomic segmentation; occupancy of houses, incomes vs. market rent, ages of inhabitants, income, family structure, and also changes in tenure. For example, in Figure 1, stresses experienced by social housing individuals can also be analysed.

Table 1. For 1-move individuals, moving between their owned property to another owned property, the percentage changes in stress types, 7 quarters before to after the move.

| Alcohol and Drug Use | 433% |

| Abortion | 350% |

| Retirement | 57% |

| Victim of Violent Crimes | 54% |

| Sexual Dysfunction | 37% |

| Acute Hospitalisation | 34% |

| Depression | 26% |

| Arranged Hospitalisation | 22% |

| Birth of Child | 20% |

| Pregnancy | 13% |

| Spouse Starting/Stopping work | 13% |

| Change in Health of Family Member | 6% |

| >70% Reduction in earned Income | 3% |

| Divorce | 2% |

| Change in Financial State | 0% |

| Congenital Deformities | 0% |

| Physical Deformities/Disability | −8% |

| Marital Separation | −12% |

| Change in Residences | −13% |

| Marriage | −28% |

| Death of a Close Family Member | −50% |

For owner-occupiers moving to another owned property, there seems to be an increase in the stresses, which are not captured in traditional stress analysis, such as drug use, childbirth and abortions. The potential explanation for this pattern is that drug use is a mechanism to alleviate stress [8], and people may need to use it to reduce their stress during home moves. Other stressors such as childbirth could be closely associated with the motivations for home moves [9]. For instance, home movers want to improve the educational outcome for existing or future children, given that homeowners are more engaging parents [10]. The link between home ownership and wanting to have children seems to be associated with stress experienced by owner-occupier movers. The marriage-induced homeownership is also shown as a driver of housing market booms [11].

The original SRRS was useful in identifying suicide victims and attempters [12]. This may be an instrument that can also be used to look at other similar social contagions, including many socioeconomic and housing movement phenomena. Whilst not within the scope of this paper, in Figure 1, it is noted that adult social housing occupants, who are high in the deprivation index, experience notably more elevated stress levels, which is not unexpected. One possible use of this instrument could be as an early warning tool for detecting socioeconomic stress associated with high levels of deprivation. This could be valuable to policymakers and public/private support services, who currently can only use lagging measures that can quantify their effects 10–20 years post-events. This tool could also potentially be used to measure the impact of changes in the socioeconomic environment or policies on a quarterly basis. Housing market is often analysed in a sociopolitical context in which the state government plays an important role [13]. Identifying various stresses/stressors can provide a valuable understanding of what circumstances the population experiences and how researchers may collectively assist. These are some future research directions.

Even though the adapted population-based SRRS instrument and methodology in the research seem to be sensitive enough to capture and quantify stresses to be used for mobility research, there are limitations of use and further work which will improve this approach. While the adapted SRRS instrument was able to capture major individual and intergenerational life stresses/stressors, it is unable to capture the full spectrum of the stresses/stressors included in the original SRRS, particularly stresses/stressors coming from social and workplace sources. Since the 1960s, new stresses and psychological conditions have been recognised and should also be included in the SRRS. Since this limitation is acknowledged, many catchalls were built into the dataset, such as depression and violent crime victimisation. These catchall characteristics and stress scores are estimated, untested, and will require further testing and development.

Figure 1. Average stress of non-movers by tenure, in time.

Figure 2. Average stress of both owners and renters, by frequency of moves within 5 years. Notes: (1 Move (n = 3609), 2 Move (n = 3753), 3 move (n = 1773)).

Figure 3. Average stress of one-off movers by tenure, 7-quarter before and after a move. Notes: 2-sided t-tests are conducted amongst different housing tenures before and after a home move. The mean stress level for an owner-to-owner increases from 22.96 to 24.91 (+1.95; p-value = 0.02303; with n = 1770). The mean stress level for renter-to-renter only shows an insignificant increase from 22.35 to 23.49 (+1.14; p-value = 0.3332; with n = 489). For renters who become homeowners after the home move, the stress level exhibited a significant increase in average stress level from 21.18 to 23.12 (+1.94; p-value = 0.03292; with n = 849). For the owner who becomes a renter after the move, the stress level slightly decreases from 24 to 23.92, but the change is statistically insignificant (−0.08; p-value = 0.4566; with n = 501).

References

- Winstanley, A.; Thorns, D.C.; Perkins, H.C. Moving House, Creating Home: Exploring Residential Mobility. Hous. Stud. 2002, 17, 813–832.

- Boston Medical Center. Housing Instability Negatively Affects the Health of Children and Caregivers: New Research Finds One in Three Low-Income Renters Face Housing Instability at Greater Risk of Poor Health and Other Hardships. ScienceDaily. 22 January 2018. Available online: www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2018/01/180122110815.htm (accessed on 29 November 2021).

- Webb, R.T.; Pedersen, C.B.; Mok, P.L.H. Adverse Outcomes to Early Middle Age Linked With Childhood Residential Mobility. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2016, 51, 291–300.

- Rumbold, A.R.; Giles, L.C.; Whitrow, M.J.; Steele, E.J.; E Davies, C.; Davies, M.J.; Moore, V.M. The effects of house moves during early childhood on child mental health at age 9 years. BMC Public Heal. 2012, 12, 583.

- Kemper, P.; Blumenthal, D.; Corrigan, J.M.; Cunningham, P.J.; Felt, S.M.; Grossman, J.M.; Kohn, L.T.; Metcalf, E.C.; Peter, R.F.S.; Strouse, R.C.; et al. The design of the community tracking study: A longitudinal study of health system change and its effects on people. Inquiry 1996, 33, 195–206.

- Crosswell, A.D.; Lockwood, K.G. Best practices for stress measurement: How to measure psychological stress in health research. Health Psychol. Open 2020, 7, 2055102920933072.

- Morris, T.; Manley, D.; Northstone, K.; Sabel, C.E. How do moving and other major life events impact mental health? A longitudinal analysis of UK children. Health Place 2017, 46, 257–266.

- Sinha, R. Chronic Stress, Drug Use, and Vulnerability to Addiction. Ann. New York Acad. Sci. 2008, 1141, 105–130.

- Tan, T.H.; Khong, K.W. The Link between Homeownership Motivation and Housing Satisfaction. Int. J. Econ. Manag. 2012, 6, 1–20.

- Grinstein-Weiss, M.; Shanks, T.R.W.; Manturuk, K.R.; Key, C.C.; Paik, J.-G.; Greeson, J.K. Homeownership and parenting practices: Evidence from the community advantage panel. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2010, 32, 774–782.

- Cheung, W.K.S.; Chan, J.T.K.; Monkkonen, P. Marriage-induced homeownership as a driver of housing booms: Evidence from Hong Kong. Hous. Stud. 2020, 35, 720–742.

- Blasco-Fontecilla, H.; Delgado-Gomez, D.; Legido-Gil, T.; de Leon, J.; Perez-Rodriguez, M.M.; Baca-Garcia, E. Can the Holmes-Rahe Social Readjustment Rating Scale (SRRS) Be Used as a Suicide Risk Scale? An Exploratory Study. Arch. Suicide Res. 2012, 16, 13–28.

- Li, L.H.; Cheung, K.S. Housing price and transaction intensity correlation in Hong Kong: Implications for government housing policy. Neth. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2016, 32, 269–287.

More

Information

Subjects:

Others

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.2K

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

21 Nov 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No