Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | David Eshun Yawson | -- | 2958 | 2022-11-17 10:54:58 | | | |

| 2 | Vivi Li | -2 word(s) | 2956 | 2022-11-18 02:59:26 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Yawson, D.E.; Yamoah, F.A. Agility in Supply Chains. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/35096 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Yawson DE, Yamoah FA. Agility in Supply Chains. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/35096. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Yawson, David Eshun, Fred A. Yamoah. "Agility in Supply Chains" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/35096 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Yawson, D.E., & Yamoah, F.A. (2022, November 17). Agility in Supply Chains. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/35096

Yawson, David Eshun and Fred A. Yamoah. "Agility in Supply Chains." Encyclopedia. Web. 17 November, 2022.

Copy Citation

The influence of the rapidly changing business environment due to the COVID-19 global pandemic presents an important organizational challenge to fresh produce export supply chains in developing countries such as Ghana. Such an inimical supply chain problem highlights the relevance of supply chain agility as a potent methodological framework to measure, monitor and evaluate these challenges in stable as well as turbulent times.

fresh produce supply chain

ombudsman agility framework

stable business environment

COVID-19 turbulent environment

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted global supply chains and negatively impacted national economies around the world [1]. This has revealed vulnerabilities in global food supply chains that are critical for human survival. Gao et al. [2] (p. 832) define supply chain disruptions as events such as fire or machine breakdown in a production facility, an unexpected surge in demand or a reduction in supply, natural disasters, or customs delays in a node of the supply chain. Food industry players in developing countries have been encouraged to explore global markets for their produce [3] to grow and further develop their businesses [4]. Such a strategy will enable them to take advantage of the potential benefits of participating in the global economy [5][6]. However, global food supply chains have been largely affected and brought under scrutiny during this pandemic as countries respond to measures and regulations to combat the pandemic [7][8][9]. Indeed, food production, transporting and shipping have been disrupted to different degrees and in different instances [10][11]. These have caused unprecedented disruptions at various operational levels in these supply chains and participating organisations. [8][11][12][13] The attendant disruptions in the demand patterns from international to the local have called into question the paradigm anchored in overreliance on global supply chains in times such as the current pandemic as against alternative parallel development of “local food” channels for these global export food chains [14][15], especially those with linkages to Sub-Saharan African food supply chains [16].

Ghana, a Sub-Saharan African lower middle-income country has been supported by global organisations to develop alternate exports, which are mainly for food products and termed as Non-Traditional Exports (NTEs) [17][18]. In Ghana, one of the main NTEs is the export of fresh pineapples. Typically, food export supply chains have been developed based on the paradigm of participating in world trade [3][6][19] with the hope of building competitiveness [20]. However, these food export supply chains, especially the fresh pineapple export chains have on many occasions suffered major incidents/shocks of changes in market regulation and in demand patterns that have bankrupted a significant number of chain actors (companies) seeking to export in the recent past [21][22][23]. Admittedly, the COVID-19 pandemic is by all measures a major global challenge which has severely impacted the export food chains. These shocks especially by this pandemic are more devastating as almost all food exporters in developing countries such as Ghana, do not have alternative competitive “local food” product outlets to rely on in times of such global pandemics [5][16]. Therefore, where almost all national country borders were closed to human and goods traffic for food exporters at some point during the pandemic as part of measures to manage the pandemic, this did create critical challenges. These issues cascade into other issues of safeguarding small and medium businesses to protecting local economies. However, these incidences and shocks encountered by actors in the fresh fruits export supply chain would have to serve as learning opportunities to build strategic agility in these chains [4][24][25][26]. This is to improve competitiveness in these chains and enable them to withstand shocks in their connection to international food supply chains [4][10][24][26][27].

2. Theoretical Foundations of Agility in Supply Chains

2.1. Horticulture Exports Supply Chain and COVID-19 Pandemic

Research on the global COVID-19 pandemic posits that it is expected to have severe economic consequences, resulting in a 3 % contraction of the world economy [22]. In this view, countries in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) are expected to be most severely affected [16]. Vos et al. [9] posited that the COVID-19 pandemic will affect food supply chains in three main ways. These are succinctly captured in Van Hoyweghen et al. [13] (p. 424) as:

- i.

-

“disruptions in international trade, stemming from an increase in trade costs due to restrictions in international mobility and quarantine measures, or stemming from trade policy measures, such as export taxes and bans, in response to the crisis.”

- ii.

-

“decline in on-farm labour, stemming from workers being unwilling or unable to work due to contamination risk and various containment measures, leading to reductions in land productivity and declining agricultural output.”

- iii.

-

“decline in productivity and farm output, caused by disruptions in distribution channels and in the provision of capital inputs and services. Effects likely differ with the type of product, and the structure and organization of supply chains.”

In addition, the literature recognises that the size of production and distribution units, the capital intensity of operations, the level of vertical coordination, the length of the chains, and the level of integration in international markets will be impacted differently resulting in supply chains exhibiting different levels of resilience to the effects of COVID-19 pandemic [28][29][30]. These will affect supply chains differently with distinctions in traditional, transitional and modern supply chains. Van Hoyweghen et al. [13] (p. 424) therefore argued that “as traditional and transitional supply chains are less integrated in international markets on the output side and oriented more toward production for domestic markets, they might be less affected by international trade disruptions.”

2.2. Horticulture Exports Supply Chain Monitoring and Evaluation

Researchers then proceed to review the literature on monitoring and evaluation frameworks for horticultural supply chains to enable the study to evaluate the effects of the global COVID-19 pandemic measures in the Ghanaian horticultural supply chain. There is a need to monitor and evaluate the horticulture export supply chain for the impact of the pandemic and present strategic agility imperatives. The literature presents studies and frameworks for optimal replenishment strategy [31] and disruption risk mitigation [2]. However, Webber and Labaste [20] posit the application of traditional monitoring approaches in most Sub-Saharan African horticultural export supply chains encounters difficulties. These include, but are not limited to systems, that are not adjusted to the measurement vocabulary of the industry; challenges in attributing industry changes to strategic interventions; inability to provide insights from monitoring into enhancing organisational practices to drive the industry; and inability to clearly delegated or insufficient resources allocated monitoring responsibilities. There is, therefore, the need for appropriate methods for monitoring performance in the Sub-Saharan African horticultural export supply chain to provide feedback for decision-making, especially in a global disruption such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Even as the markets for the exporters are driven by foreign demand with high continual business environment changes.

Currently, the literature acknowledges the PAID (Process indicators, Action indicators, Investment indicators, Delivered results) framework as the most comprehensive evaluation approach used for supply chains [20]. This framework not only measures co-investment by stakeholders in addition to delivered results and can be used in supply chain projects when proper benchmarks are determined by chain actors. However, it has not been designed to measure impacts experienced by actors in the supply chain and various systems components of the supply chain. The framework focuses on performance chain-wide by (1) implementation of strategy and (2) increases in productivity [20]. Therefore, leaving a gap of in need for a framework to measure the effects on the systems component of the supply chains.

2.3. A Theoretical Lens for Supply Chain Agility

Supply chain agility seen as strategic agility requires the competence to manage, sense changes and mobilize resources to adjust to change caused by strategic discontinuities, business environment and disruptions. Thus, supply chain agility could be considered a dynamic capability, since the literature defines dynamic capability as the ability to “integrate, build and reconfigure internal and external competencies to address rapidly changing environments” (Teece, [32] (p. 516)). Do et al. [33] present research that has employed dynamic capability as a theoretical lens to enhance understanding of strategic supply chain agility [32][34][35][36][37].

The framework to sense the required supply chain agility prerequisites and redesign variables as discussed in Section 2.2 has been sparsely researched and has left a gap in the measurement of supply chain components. Since supply chain agility as strategic agility is a management decision and Mentzer et al. [38] proposed a broader and generalised definition for supply chain management as the systematic, strategic coordination of business functions and organisation tactics across actors within the supply chain, ultimately for improving the long-term performance of the supply chain actors and the supply chain as a whole. In addition, from the system dynamics view and the “logistical concept”, a supply chain scenario consists of a managed system, managing system, information and organization [39].

Therefore, to ensure the application of supply chain agility and to implement it, there are identified variables in the supply chain that could be redesigned to achieve the required agile configuration of the supply chain. These are the supply chain redesign variables. A supply chain redesign variable is defined as a management decision variable at the strategic, tactical or operational level that determines the setting of one of the descriptive elements of the managed, managing, information system or organization structure [28]. Vorst [40] (p. 64) classifies these redesign variables in a supply chain as shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Classification of Supply Chain Redesign Variables. Adapted from Vorst (2000) [40] (p. 64).

| Managed System | Managing System | Information System | Organization |

|---|---|---|---|

| Network design Facility design Resource and product characteristics |

Hierarchical decision levels Type of decision making Position of the Customer order decoupling point (CODP) Level of coordination

|

Transactional IT systems Analytical IT systems |

Division of tasks Division of authority and responsibilities. |

Additionally, Yawson and Aguiar [41][42] developed elements of the components that will require supply chain agility in developing countries’ horticultural export supply chains based on the redesign variables in Table 1 and is presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Typology of Fresh Produce Horticultural Export Supply Chain Elements of the Components Requiring Agility.

| Supply Chain Management Concept Component | Elements of The Supply Chain Components Requiring Agility |

|---|---|

| Managed System (Infrastructure) (MDS) |

Cold chain infrastructure_(MDS 1) |

| Post-harvest infrastructure_(MDS2) | |

| Packaging material (e.g., pallets, cartons)_(MDS3) | |

| Field infrastructure for production_(MDS4) | |

| Field infrastructure for labour_(MDS5) | |

| Internal logistics infrastructure (e.g., transport)_(MDS6) | |

| External logistics infrastructure (e.g., shipping, air)_(MDS7) | |

| Road infrastructure_(MDS8) | |

| Environment (e.g., taxes, regulation)_(MDS9) | |

| Production infrastructure_(MDS10) | |

| Input suppliers (e.g., fertilizers, pesticides)_(MDS11) | |

| Planting material production_(MDS12) | |

| Distribution network design_(MDS13) | |

| Product varieties_(MDS14) | |

| Land for production_(MDS15) | |

| Irrigation facilities_(MDS16) | |

| Managing System (Management) (MGS) |

Management structure_(MGS1) |

| Management Systems_(MGS2) | |

| Decision Making_(MGS3) | |

| Level of coordination in the organization_(MGS4) | |

| Level of coordination in the supply chain_(MGS5) | |

| Information System (INS) |

Information exchange system_(INS1) |

| Electronic information systems_(INS2) | |

| Electronic information management_(INS3) | |

| Databases on markets and competition_(INS4) | |

| Standardized information system for supply chain integration _(INS5) | |

| Organization (ORG) |

Definition of organizational logistical objectives_(ORG1) |

| Definition of supply chain logistical objectives_(ORG2) | |

| Definition of organizational logistical performance indicators_(ORG3) | |

| Definition of supply chain logistical performance indicators_(ORG4) | |

| Training of staff (internal and external)_(ORG5) |

With the disruptive change due to the COVID-19 pandemic in fresh produce supply chains, therefore, dealing with uncertainty denotes whether or when a certain event occurs. However, dealing with uncertainty requires evaluating the implications if certain events were to occur. In the case of the fresh produce supply chain, strategic agility would be the supply chain actor organizations or chain-wide supply chain response. Generally, for fresh produce supply chains, horticultural producers adopt and develop various strategies in order to survive and develop [43]. These strategies are based on three key aspects: (1) organisational innovation; (2) production innovation; and (3) product innovation [44].

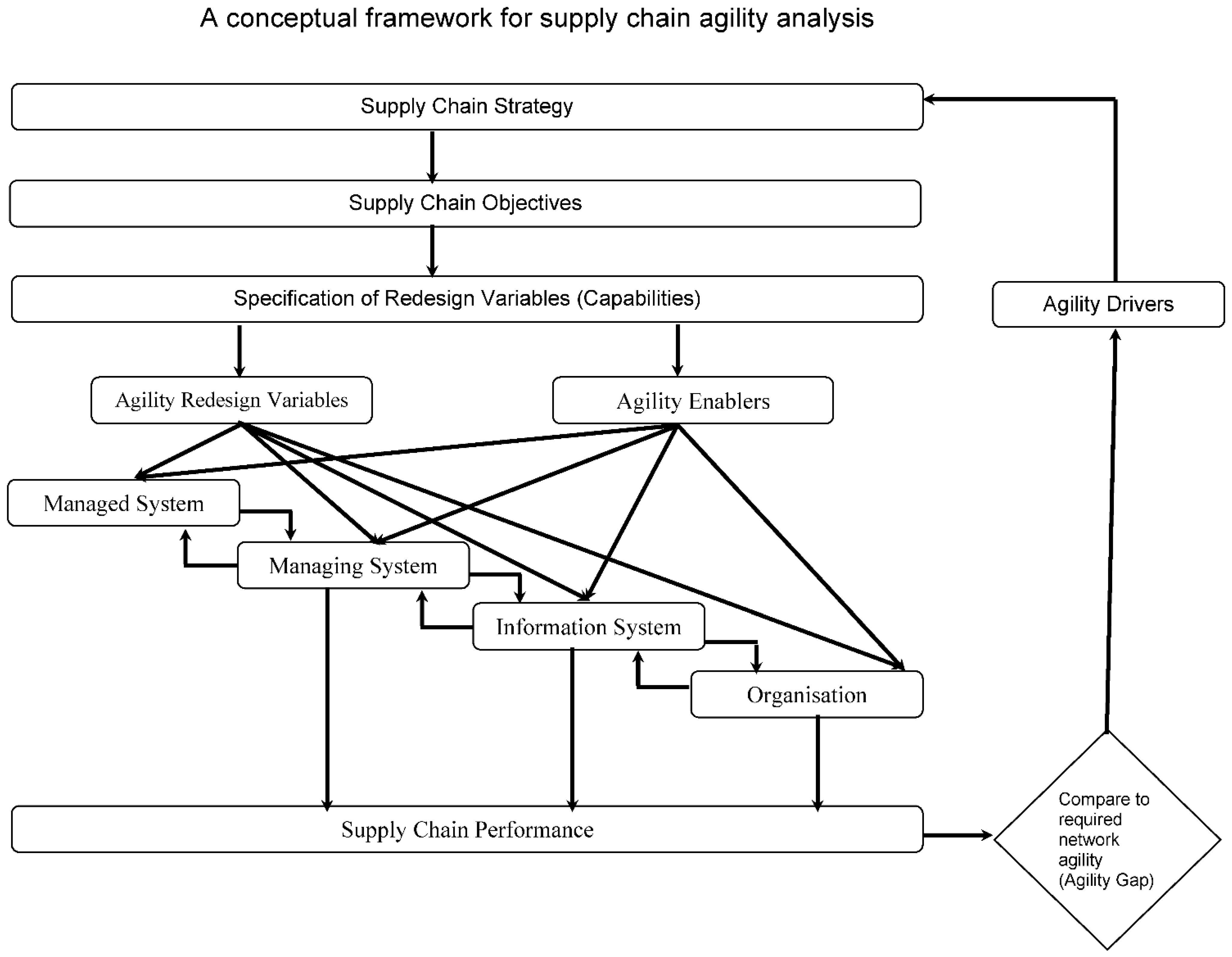

Therefore, researchers adopt the framework by Yawson and Aguiar [41] and Yawson and Aguiar [42] to identify components and elements in a developing countries’ horticultural export supply chain that required agility due to the disruption of the COVID-19 pandemic. This is to provide insight into supply chain evaluation in the horticultural export development context to enable the building of the critical responsive strategy required to compete. In the framework, the external and internal environment are conceptualised to affect the four theoretical (logistical concept) components of the supply chain, the managed system (infrastructure), managing system (management), information system and organisation system. The framework is shown in Figure 1. The relationships of the agility drivers to the various components of the supply chain are presented, ensuring the framework account for internal and external environmental factors (politics, economics, society and technology) [45] and also four agility dimensions: cooperating to enhance competitiveness, enriching the customer, mastering change and uncertainty, and leveraging the impact of people and information [46]. Additionally, the framework also accounts for companies as part of a network, showing the affected and the level of agility of the supply chain [47]. From the framework in Figure 1, the change factors relate to the following components of the supply chain elements:

Figure 1. Conceptual Framework for Supply Chain Agility Analysis.

-

The managed system: The supply chain actors with specified roles in the supply chain and their required infrastructure [48], which can be viewed from three levels: network design, facility design, and resource characteristics.

-

The managing system: This component plans, controls and coordinates the business processes in the supply chain to ensure the realization of the logistical objectives within the limitations of the supply chain configuration and strategic supply chain objectives [49].

-

The information system: This component provides and coordinates the information for the managing system for decision-making and control of actions.

-

The organisation structure: This component comprises two main elements [50]: the establishment of tasks and their coordination to realize set objectives.

-

Agility drivers: These are internal or external factors in the business environment influencing the required level of business agility. Zhang and Sharifi [51] (p. 498) define “agility drivers as changes/pressures from the business environment that necessitate a company to search for new ways of running its business in order to maintain its competitiveness”.

-

Specification of redesign variables (capabilities): These are the essential capabilities variable needed by the company in order to respond positively to utilising the business environment changes.

-

Agility gaps: Agility gaps arise when the firm has difficulty in acquiring the level of agility to respond to business environment changes in a timely and cost-effective manner.

-

Agility enablers: Agility enablers are the required variables for a business to enhance its strategic agility. The model presents enablers of supply chain actors and supply chain strategic agility.

-

Supply chain performance: Supply chain performance is the level at which a supply chain fulfils end-user requirements based on performance indicators and the given total cost to the supply chain [40].

-

Agility redesign variable: This is management decisions at the strategic level that determines one of the logistic concept components of the supply chain (managed, managing, information system and organisation structure).

The framework operates in two steps: Firstly, it identifies the elements of the components of the supply chain that requires agility by identifying elements of component that actors of the chain find difficult in meeting or changing to meet in the supply chain. This is done through a questionnaire sent to actors in the supply chain with questions on the elements of the components shown in Table 2. Secondly, the questionnaire is then analysed for the Agility gap using an index interpreted and interventions prescribed.

The Agility Gap Index is adapted from the work of van Oosterhout et al. [47]. They developed a business Agility Gap index for which they argue that if businesses find it difficult to cope with major changes which go beyond their normal flexibility, they are termed to have faced an agility gap. The interview instrument for the framework interrogates strategic agility with a two-stage question approach. The first step asks the participant “To what extent are changes in the current business environment affecting supply chain elements in your business?” (Then, a list of the elements of the components follows). The items are scored on a Likert-5point scale anchored on 1 (Very low) to 5 (Very high). For items representing processes that score 4 or 5 (high and very high extent of change, respectively) a follow-up question. Therefore, whole business entities, supply change actors and specific supply change processes could be termed to have an agility gap. The changes required are termed business change and the factors causing these are business environment change factors. In the second step, the degree of the impact due to the business environment change factor is measured with a follow-up question in the survey instrument for items representing processes that score 4 or 5 (high and very high extent of change, respectively) on a Likert-5point scale asking the participant to indicate the level of difficulty in having to cope with the change. The responses to the follow-up questions are also scored on a Likert-5point scale of difficulty anchored on 1 (Very low) to 5 (Very high). These are then computed as an Agility gap index score with a percentage. Therefore, Agility gap index scores can be computed for elements of the supply change components, an aggregate of the components in supply chains and whole supply chains [41][42]. The results are interpreted according to a scale developed by Oosterhout et al. [47]. The agility gap index calculated as a ratio in percentage is scaled to a number between 0% (no Agility gap at all) and 100% (largest Agility gap possible). These are classified as ‘most urgent’ gaps (ratios ≥ 60%), ‘high urgency’ gaps (ratios > 50% and < 60%), ‘lower level of urgency’ gaps (ratios > 40% and ≤ 50%), ‘Normal’ gaps (ratios < 40%) and ‘No Gap at All’ (ratios = 0) using a scale by van Oosterhout et al. [47]. The higher the agility gap index ratio percentage, the more urgent the agility gap. According to Oosterhout et al. [47] if businesses find it difficult to cope with major changes, which go beyond their normal level of flexibility, they are faced with an agility gap and need intervention. Therefore, the supply chain agility methodological framework has the potential as a potential panacea to identify components of the horticulture export supply chain for the development of a responsive strategy to resolve fresh produce export chain challenges in a turbulent (COVID-19) business environment.

References

- IMF. World Economic Outlook, 2020 (April), the Great Lockdown. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2020/04/14/weo-april-2020 (accessed on 24 February 2022).

- Gao, S.Y.; Simchi-Levi, D.; Teo, C.P.; Yan, Z. Disruption risk mitigation in supply chains: The risk exposure index revisited. Oper. Res. 2019, 67, 831–852.

- World Bank. World Development Report 2008: Agriculture for Development; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2008.

- Giuliani, E.; de Marchi, V.; Rabellotti, R. Do global value chains offer developing countries learning and Innovation opportunities? Eur. J. Dev. Res. 2017, 30, 389–407.

- Feyaerts, H.; Van den Broeck, G.; Maertens, M. Global and local food value chains in Africa: A review. Agric. Econ. 2020, 51, 143–157.

- Gereffi, G. Global value chains in a post-Washington consensus world: Shifting governance structures, trade patterns and development prospects. Rev. Int. Political Econ. 2014, 21, 9–37.

- Laborde, D.; Martin, W.; Vos, R. Impacts of COVID-19 on global poverty, food security and diets. Agric. Econ. 2021, 52, 375–390.

- Reardon, T.; Bellemare, M.F.; Zilberman, D. How COVID-19 May Disrupt Food Supply Chains in Developing Countries. Retrieved from IFPRI Blog Post. 2020. Available online: https://www.ifpri.org/blog/how-covid-19-may-disrupt-food-supply-chains-developingcountries (accessed on 20 February 2022).

- Vos, R.; Martin, W.; Laborde, D. How Much Will Global Poverty Increase Because of COVID-19? 2020. Available online: https://www.ifpri.org/blog/how-much-will-global-poverty-increase-because-covid-19 (accessed on 20 February 2022).

- Glauber, J.; Laborde, D.; Martin, W.; Vos, R. COVID-19: Trade restrictions are worst possible response to safeguard food security. In COVID-19 & Global Food Security; Swinnen, J., McDermott, J., Eds.; International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI): Washington, DC, USA, 2020; pp. 66–68.

- Hobbs, J.E. Food supply chains during the COVID-19 pandemic. Can. J. Agric. Econ. 2020, 68, 171–176.

- Reardon, T.; Swinnen, J. COVID-19 and Resilience Innovations in Food Supply Chains. Retrieved from IFPRI Blog Post. 2020. Available online: https://www.ifpri.org/blog/covid-19-and-resilience-innovations-food-supply-chains (accessed on 20 February 2022).

- Van Hoyweghen, K.; Fabry, A.; Feyaerts, H.; Wade, I.; Maertens, M. Resilience of global and local value chains to the COVID-19 pandemic: Survey evidence from vegetable value chains in Senegal. Agric. Econ. 2021, 52, 423–440.

- Christiaensen, L.; Rutledge, Z.; Taylor, J.E. Viewpoint: The future of work in agri-food. Food Policy 2021, 99, 101963.

- Panwar, R. It’s time to develop local production and supply networks. Strategy Insight Note. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2020, 28, 1–3. Available online: https://cmr.berkeley.edu/2020/04/local-production-supply-networks/ (accessed on 24 February 2022).

- McCullough, E. Labor productivity and employment gaps in Sub-Saharan Africa. Food Policy 2017, 67, 133–152.

- Trienekens, J.; Willems, S. Innovation and Governance in International Food Supply Chains: The Cases of Ghanaian Pineapples and South African Grapes. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2007, 10, 42–63.

- Legge, A.; Orchard, J.; Graffham, A.; Greenhalgh, P.; Kleih, U. The Production of Fresh Produce in Africa for Export to the United Kingdom: Mapping Different Value Chains; Natural Resources Institute: Chatham, UK, 2006.

- Amanor, K.S. Global Food Chains, African Smallholders and World Bank Governance. J. Agrar. Change 2009, 9, 247–262.

- Webber, M.C.; Labaste, P. Building Competitiveness in Africa’s Agriculture: A Guide to Value Chain Concepts and Applications; The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2010.

- Asante-Poku, N.A. Global Value-Chain Participation and Development: The Experience of Ghana’s Pineapple Export Sector. In Future Fragmentation Processes; The Commonwealth: London, UK, 2017; Volume 96.

- Kleemann, L. Organic Pineapple Farming in Ghana a Good Choice for Smallholders? J. Dev. Areas 2016, 50, 109–130.

- Fold, N.; Gough, K.V. From smallholders to transnationals: The impact of changing consumer preferences in the EU on Ghana’s pineapple sector. Geoforum 2008, 39, 1687–1697.

- Dupouy, Ε.; Gurinovic, M. Sustainable food systems for healthy diets in Europe and Central Asia: Introduction to the special issue. Food Policy 2020, 96, 101952.

- Falkowski, J. Resilience of farmer-processor relationships to adverse shocks: The case of dairy sector in Poland. Br. Food J. 2015, 117, 2465–2483.

- Jacobi, J.; Mukhovi, S.; Llanque, A.; Augstburger, H.; Käser, F.; Pozo, C.; Peter, M.N.; Delgado, J.M.F.; Kiteme, B.P.; Rist, S.; et al. Operationalizing food system resilience: An indicator-based assessment in agroindustrial, smallholder farming, and agroecological contexts in Bolivia and Kenya. Land Use Policy 2018, 79, 433–446.

- Bourlakis, M.A.; Weightman, P.W.H. Food Supply Chain Management; Blackwell Publishing Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2004.

- Vorst, J.G.A.J.; Beulens, A.J.M. A Research Model for the Redesign of Food Supply Chains. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 1999, 2, 161–174.

- Ryder, R.; Fearne, A. Procurement best practice in the food industry: Supplier clustering as a source of strategic competitive advantage. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2003, 8, 12–16.

- Sheffi, Y.; Rice, J.B., Jr. A supply chain view of the resilient enterprise. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2005, 47, 41. Available online: https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/a-supply-chain-viewof-the-resilient-enterprise/ (accessed on 1 November 2010).

- Corsini, R.R.; Costa, A.; Fichera, S.; Framinan, J.M. A new data-driven framework to select the optimal replenishment strategy in complex supply chains. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2022, 55, 1–25.

- Teece, D.J.; Pisano, G.; Shuen, A. Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 509–533.

- Do, Q.N.; Mishra, N.; Wulandhari, N.B.I.; Ramudhin, A.; Sivarajah, U.; Milligan, G. Supply chain agility responding to unprecedented changes: Empirical evidence from the UK food supply chain during COVID-19 crisis. Supply Chain Manag. 2021, 26, 737–752.

- Gligor, D.M.; Holcomb, M.C.; Feizabadi, J. An exploration of the strategic antecedents of firm supply chain agility: The role of a firm’s orientations. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2016, 179, 24–34.

- Eckstein, D.; Goellner, M.; Blome, C.; Henke, M. The performance impact of supply chain agility and supply chain adaptability: The moderating effect of product complexity. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2015, 53, 3028–3046.

- Whitten, G.D.; Green, K.W.; Zelbst, P.J. Triple-a supply chain performance. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2012, 32, 28–48.

- Blome, D.; Schoenherr, T.; Rexhausen, C. Antecedents and enablers of supply chain agility and its effect on performance: A dynamic capabilities perspective. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2013, 51, 1295–1318.

- Mentzer, J.T.; DeWitt, W.; Keebler, J.S.; Min, S.; Nix, N.W.; Smith, C.D.; Zacharia, Z.G. Defining supply chain management. J. Bus. Logist. 2001, 22, 1–25.

- Ribbers, A.M.A.; Verstegen, M.F.G.M. Toegepaste Logistiek; Kluwer Bedrijfswetenschappen: Deventer, The Netherlands, 1992.

- Vorst, J.G.A.J. Effective Supply Chains: Generating, Modeling and Evaluating Supply Chain Scenarios. Ph.D. Thesis, Wageningen University, The Hague, The Netherlands, 2000.

- Yawson, D.E.; Aguiar, L.K. Agility in the Ghanaian International Pineapple Supply Chain. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Fresh Produce Supply Chain Management, Chiang Mai, Thailand, 6–10 December 2006; Available online: http://www.fao.org/ag/ags/subjects/en/agmarket/chiangmai/aguiar.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2007).

- Yawson, D.E.; Aguiar, L.K. Agility in the Ghanaian international pineapple supply chain. Presented at the 17th Annual Forum and Symposium IAMA Conference, Parma, Italy, 14–17 June 2007; RAPRA Publication 2007/21. UN Food and Agriculture Organisation: Rome, Italy, 2007; pp. 200–213.

- Thoen, R. The EU market for fresh horticultural products: Trends and opportunities for Sub-Sahara Africa producers. In Potential Contribution of Horticulture to Growth Strategies in Sub-Sahara Africa: Developing Horticulture Supply Chains for Growth and Poverty Reduction in Sub-Saharan Africa; World Bank Institute Seminar: Washington, DC, USA, 2004.

- Capitanio, F.; Coppola, A.; Pascucci, S. Indicators for drivers of innovation in the food sector. Br. Food J. 2009, 111, 820–838.

- Palmer, A.; Hartley, B. The Business Environment; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2002.

- Goldman, S.; Nagel, R.; Preiss, K. Agile Competitors and Virtual Organizations; Van Nostrand Reinhold: New York, NY, USA, 1995.

- Van Oosterhout, M.; Waarts, E.; van Hillegersberg, J. Change factors requiring agility and implications for IT. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2006, 15, 132–145.

- Beulens, A.J.M. Continuous replenishment in food chains and associated planning problems. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Advances in Methodology and Software for Decision Support Systems, Luxemburg, 8–10 September 1996; IIASA: Laxenburg, Austria, 1996.

- Bertrand, J.W.M.; Wortmann, J.C.; Wijngaard, J. Production Control—A Structural and Design-Oriented Approach; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1990.

- Mintzberg, H. The Structuring of Organisations; Prentice-Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1979.

- Zhang, Z.; Sharifi, H. A methodology for achieving agility in manufacturing organizations. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2000, 20, 496–512.

More

Information

Subjects:

Management

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

552

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

18 Nov 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No