| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Camila Xu | -- | 1386 | 2022-10-31 01:35:18 |

Video Upload Options

Reference Point Indentation (RPI) refers to a specialized form of indentation testing. RPI utilizes a unique method of measurement by establishing a relative reference point at the location of measurement. This unique capability makes it possible to measure materials that are in motion, oddly shaped, visco-elastic, or that may be coated or covered by another, softer material. Unlike traditional indentation testing, RPI testing uses the location of measurement as the relative displacement reference position. Indentation itself is perhaps the most commonly applied means of testing the mechanical properties of materials. The technique has its origins in the Mohs scale of mineral hardness, in which materials are ranked according to what they can scratch and are, in turn, scratched by. The characterization of solids in this way takes place on an essentially discrete scale, so much effort has been expended in order to develop techniques for evaluating material hardness over a continuous range. Hence, the adoption of the Meyer, Knoop, Brinell, Rockwell, and Vickers hardness tests. More recently (ca. 1975), nanoindentation techniques have been established as the primary tool for investigating the hardness of small volumes of material. However, even more recently (ca. 2006), interest in measuring functional roles of biomaterials drove the development of the Reference Point Indentation technique. New research in field such as biomaterials has led scientists to begin considering materials as complex systems that behave differently than the constituent parts. For example, materials like bone are hierarchical and made of many components including calcium, collagen, water, and non-collagenous proteins. Each of these components has unique material properties. When combined to form bone, the function of the tissue is different than any one constituent. Understanding this mechanical system is becoming a new field of research called Materiomics. RPI specifically aims to aid materiomics researchers understand the functional capabilities of these types of materials at a relevant length-scale.

1. Background

In a traditional indentation test (macro or micro indentation), a hard tip whose mechanical properties are known (frequently made of a very hard material like diamond) is pressed into a sample whose properties are unknown. The load placed on the indenter tip is increased as the tip penetrates further into the specimen and soon reaches a user-defined value. At this point, the load may be held constant for a period or removed. The area of the residual indentation in the sample is measured and the hardness, [math]\displaystyle{ H }[/math], is defined as the maximum load, [math]\displaystyle{ P_{max} }[/math], divided by the residual indentation area, [math]\displaystyle{ A_r }[/math], or

[math]\displaystyle{ H=\frac{P_{max}} {A_{r}} }[/math].

For most non-Reference Point Indentation techniques, the projected area may be measured directly using light microscopy. As can be seen from this equation, a given load will make a smaller indent in a "hard" material than a "soft" one.

This technique is limited due to large and varied tip shapes, with indenter rigs which do not have very good spatial resolution (the location of the area to be indented is very hard to specify accurately). Comparison across experiments, typically done in different laboratories, is difficult and often meaningless. Reference Point Indentation improves on these macro and micro indentation tests by indenting on the microscale with a very precise tip shape, high spatial resolutions to place the indents, and by providing real-time load-displacement (into the surface) data while the indentation is in progress.

2. Reference Point Indentation

What makes RPI different?

Unlike traditional methods which require restrictive sample preparation, RPI sets a local reference point that allows materials to be tested in their unmodified natural state. In tissue research, RPI makes in vivo measurements possible, enabling material properties to be measured longitudinally over time within a single sample or animal.

Value of RPI for tissue research:

Can rapidly measure material properties on previously impossible samples (in vivo, in vitro and ex vivo small samples without preparation). Translational. Currently used for both laboratory and clinical research projects.

Tissue Examples:

Hard – [ex: Bone]: Micron-level indentation studies enable direct determination of bone tissue quality. Allowing improved understanding of failure dynamics without compromising whole bone integrity.

Dynamic Measurement Capability:

A unique use for Reference Point Indentation measurements is to measure dynamic changes of a material by cyclic indentation at a set rate. The change in the load-displacement curve as a function of cycle can be used to calculate visco-elastic properties of materials, such as tan delta or dynamic phase-change. These capabilities are being used to investigate materials which undergo dynamic loading such as bone, cartilage, and spinal disc.

How does RPI Work?

Reference Point Indentation uses a unique probe assembly to establish a surface-localized reference point to accurately “feel” a material. One specific form of RPI uses a multi-probe assembly that includes a test probe contained within the sheath of an outer reference probe. In Reference Point Indentation large loads and small tip sizes are used, so the indentation area may be up to a few hundred square micrometres. Atomic force microscopy or scanning electron microscopy techniques may be utilized to image the indentation, but can be quite cumbersome and requires that the measurement site be exposed and potentially altered in order to make the measurement. Instead, an indenter with a geometry known to high precision is employed.

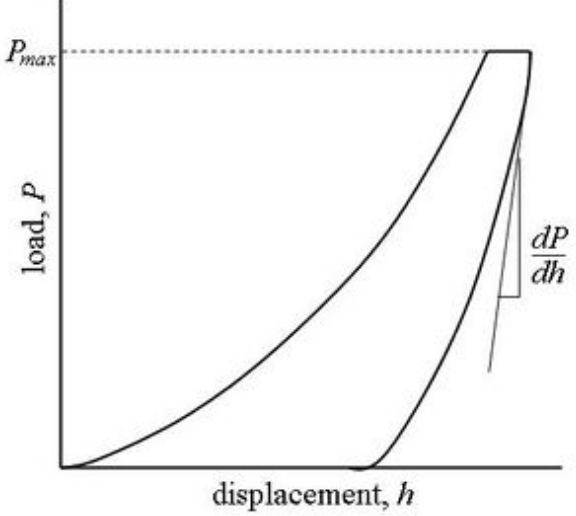

During the course of the modified instrumented indentation process, a record of the depth of penetration is made, and then the area of the indent is determined using the known geometry of the indentation tip. While indenting various parameters, such as load and depth of penetration, can be measured. A record of these values can be plotted on a graph to create a load-displacement curve (such as the one shown in Figure 1). These curves can be used to extract more sophisticated mechanical properties of the material.[1][2][3]

Each load-displacement curve can be directly analyzed to determine indentation distance, relative stiffness, and energy dissipated.

3. Software

Software is the best method to analyze the Reference Point Indentation load versus displacement curves for mechanical property calculations.

4. Devices

The construction of a depth-sensing Reference Point Indentation system is made possible by the inclusion of very sensitive displacement and load sensing systems. Load transducers must be capable of measuring forces in the newtonto micronewton range and displacement sensors are very frequently capable of sub-micrometer resolution. Environmental isolation is not crucial to the operation of the instrument because the reference point is isolated to the location of measurement. Vibrations transmitted to the device, fluctuations in atmospheric temperature and pressure, and thermal fluctuations of the components during the course of an experiment can cause errors, but these errors are typically not significant.

There are currently 2 Reference Point Indentation devices available. One is the BioDent Reference Point Indenter which is designed for laboratory research and the other is called the OsteoProbe which is designed for clinical research. Neither devices is approved for diagnostic medical procedures. Clinical diagnostic devices are currently under development (2014).

5. Limitations

Conventional microindentation methods for calculation of Modulus of elasticity (Young's Modulus) (based on the unloading curve) are limited to linear, isotropic materials. Problems associated with the "pile-up" or "sink-in" of the material on the edges of the indent during the indentation process remain a problem that is still under investigation. Reference Point Indentation offers an additional draw back in that measurements of tissues, like bone, that are rough and/or covered by soft tissue make accurate contact area measurements difficult. With an unknown contact area, measures of traditional elastic modulus become difficult to interpret. Additionally, in many instances the tissue being measured experience forces that are beyond the yield point and are no longer in the elastic region of behavior.

It is possible to measure the pile-up contact area using computerized image analysis of atomic force microscope (AFM) images of the indentations.[4] This process also depends on the linear isotropic elastic recovery for the indent reconstruction.

6. History

Reference Point Indentation was invented by physicist Dr. Paul K. Hansma at the University of California, Santa Barbara in 2006. His contributions to the field of Atomic Force Microscopy are well documented; particularly the invention of the Multi-Mode AFM. Reference Point Indentation is now being used at various research universities on a wide range of tissues including, but not limited to, bone, cartilage, tendon, muscle, sclera, and cornea.

References

- W.C. Oliver and G.M. Pharr. "Measurement of hardness and elastic modulus by instrumented indentation: Advances in understanding and refinements to methodology". "J. Mater. Res." 19 (2004), 3. (review article) http://journals.cambridge.org/action/displayAbstract?fromPage=online&aid=8029498&fileId=S0884291400085800

- Fischer-Cripps, A.C. Nanoindentation. (Springer: New York), 2004. W.C. Oliver, G.M. Pharr J. Mater. Res. 7 (1992) 1564. Y.-T. Cheng, C.-M. Cheng, "Scaling, dimensional analysis, and indentation measurements", "Mater. Sci. Eng." R, 44 (2004) 91. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0927796X04000415

- J. Malzbender, J.M.J. den Toonder, A.R. Balkenende, G. de With, "A Methodology to Determine the Mechanical Properties of Thin Films, with Application to Nano-Particle Filled Methyltrimethoxysilane Sol-Gel Coatings", "Mater. Sci. Eng." Reports 36 (2002) 47. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0927796X01000407

- Shuman, David; "Computerized Image Analysis Software for Measuring Indents by AFM", "Microscopy-Analysis", P 21, (May 2005) http://www.microscopy-analysis.com/magazine/issues/computerized-image-analysis-software-measuring-indents-afm