Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ghaleb Adnan Husseini | -- | 4802 | 2022-10-28 04:41:58 |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Ali, A.A.; Abuwatfa, W.H.; Al-Sayah, M.H.; Husseini, G.A. Gold-Nanoparticle Hybrid Nanostructures for Multimodal Cancer Therapy. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/31690 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Ali AA, Abuwatfa WH, Al-Sayah MH, Husseini GA. Gold-Nanoparticle Hybrid Nanostructures for Multimodal Cancer Therapy. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/31690. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Ali, Amaal Abdulraqeb, Waad H. Abuwatfa, Mohammad H. Al-Sayah, Ghaleb A. Husseini. "Gold-Nanoparticle Hybrid Nanostructures for Multimodal Cancer Therapy" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/31690 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Ali, A.A., Abuwatfa, W.H., Al-Sayah, M.H., & Husseini, G.A. (2022, October 28). Gold-Nanoparticle Hybrid Nanostructures for Multimodal Cancer Therapy. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/31690

Ali, Amaal Abdulraqeb, et al. "Gold-Nanoparticle Hybrid Nanostructures for Multimodal Cancer Therapy." Encyclopedia. Web. 28 October, 2022.

Copy Citation

With the urgent need for bio-nanomaterials to improve the currently available cancer treatments, gold nanoparticle (GNP) hybrid nanostructures are rapidly rising as promising multimodal candidates for cancer therapy. Gold nanoparticles (GNPs) have been hybridized with several nanocarriers, including liposomes and polymers, to achieve chemotherapy, photothermal therapy, radiotherapy, and imaging using a single composite. The GNP nanohybrids used for targeted chemotherapy can be designed to respond to external stimuli such as heat or internal stimuli such as intratumoral pH.

gold-nanoparticle hybrid nanostructures

multimodal therapy

photothermal therapy

triggered drug delivery

1. Introduction

A wide range of bio-nanomaterials is becoming a subject of interest for biomedical purposes. Of those nanomaterials, FDA-approved gold nanoparticles have been well-studied for their promising role in improving drug delivery and imaging [1][2][3]. Gold nanoparticles (GNPs), which are composed of gold atom aggregates of sizes ranging from 1 to 100 nm [4], have been extensively studied and utilized for biomedical applications, including the diagnosis and/or treatment of cancer [5][6], among others [7][8]. This is mainly due to their unique localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) and photothermal conversion ability, as reviewed by Vines et al. [9] and Sztandera et al. [10]. LSPR results when nanoparticles are irradiated with light of a particular wavelength, causing the surface electrons in the metal conduction band to oscillate coherently, resulting in the separation of their surface charge (dipole oscillation) [9][11]. Although all noble metal nanoparticles exhibit LSPR, GNPs are classified as the most stable, rendering them advantageous over other LSPR-characterized nanoparticles [12].

Stemming from their LSPR property, GNPs possess the ability to convert light (i.e., near-infrared (NIR) light) to heat in a process known as photothermal conversion. Photothermal conversion makes GNPs suitable candidates for the thermal ablation of cancer cells in a noninvasive treatment strategy known as photothermal therapy (PTT) [9][13]. Eradicating tumor cells via heat is especially advantageous in cancer therapy due to cells’ higher sensitivity to heat compared with normal ones [14]. Furthermore, heat generation was reported to intensify chemotherapeutic cytotoxic effects by increasing the blood vessel permeability, thereby allowing more drugs to reach and accumulate at the tumor site. Heat can also trigger the release of encapsulated drugs from heat-sensitive carriers, thereby achieving more tumor-specific drug release and avoiding drug-associated, off-target, unwanted side effects [15][16][17][18]. Although other nanomaterials, such as magnetic nanoparticles, can induce hyperthermia, GNP-associated photothermal conversion provides practical advantages over other nanomaterials. For instance, magnetic nanoparticles require the application of an alternating magnetic field to the whole body to trigger heat generation. In contrast, GNP photothermal conversion involves the application of a near-infrared (NIR) laser specifically to the site of interest rather than to the whole body [9]. Furthermore, GNPs were found to be relatively safer than other metal nanoparticles [19], with a safety profile that depends on several factors, including size, shape [9], and concentration [20].

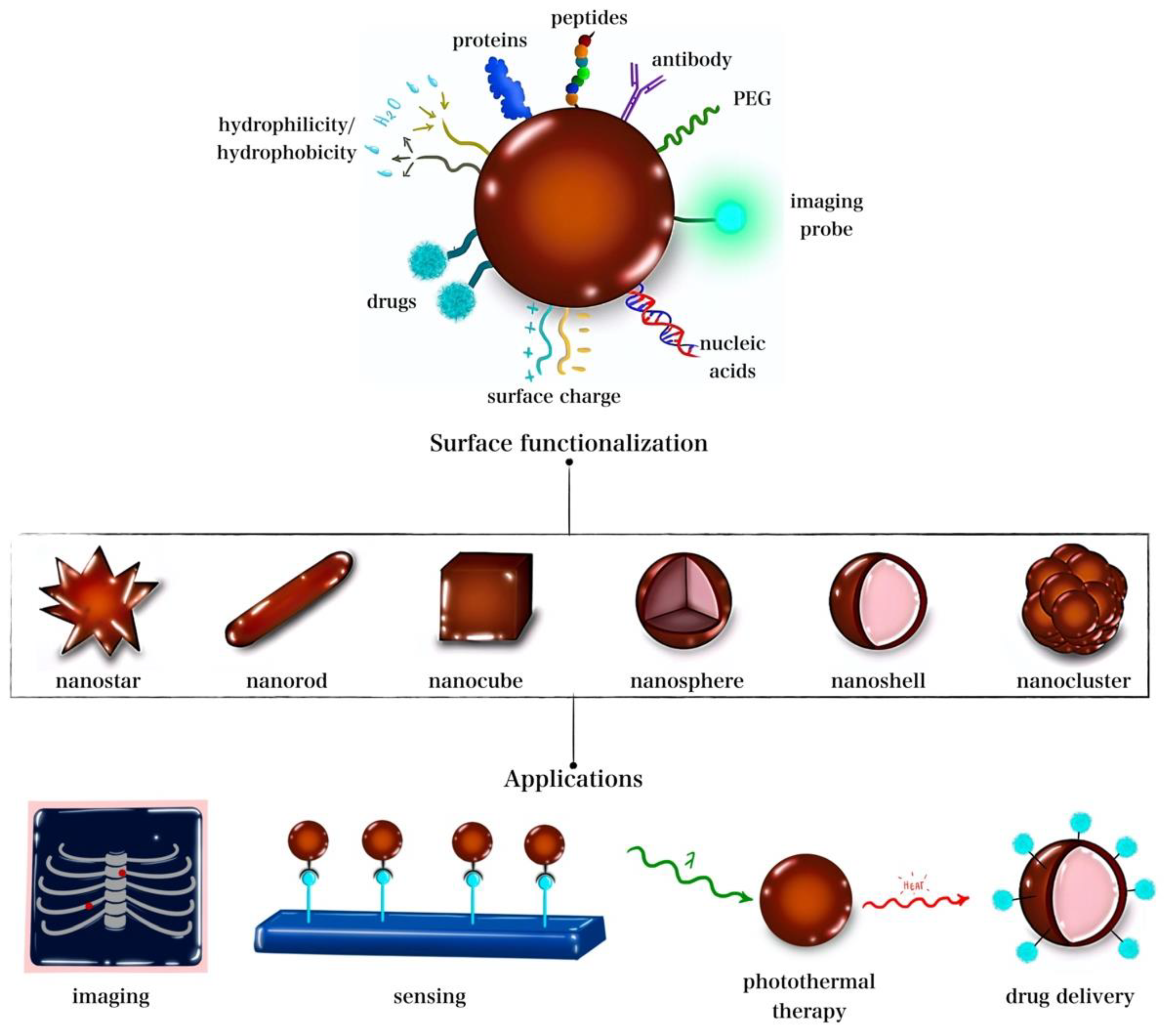

Moreover, GNPs’ various possible sizes, shapes, and surface functionalizations provide a level of control over the nanoparticles and allow further tailoring of their properties for specific applications to be conducted [21]. For instance, Yang et al. [22] reported that gold nanostars were found to possess higher photothermal conversion abilities than spherical or rod-shaped GNPs. In contrast, spherical GNPs showed higher uptake by cells compared to gold nanorods. Chan et al. reported that the size of spherical GNPs also influenced their uptake levels, with the highest degree of uptake being achieved for a size of 50 nm [23]. Furthermore, GNPs also serve as efficient radiosensitizing agents due to their high atomic number and ability to absorb X-rays, which makes them good candidates for tumor radiosensitization [24]. Their strong X-ray absorption abilities make them suitable as computed tomography (CT) contrast agents [25]. In fact, GNPs were reported to improve radiotherapy [24][26][27] and CT imaging [25][28][29]. Hence, GNPs can provide a multimodal therapeutic platform capable of chemotherapy delivery, PTT, radiotherapy, and imaging.

Multimodal therapeutic platforms have been explored to overcome tumor resistance to chemo-radiotherapy. Tumors are known to develop resistance to both chemotherapy and radiotherapy, rendering them eventually ineffective. Therefore, combining chemotherapy/radiotherapy with the hyperthermic annihilation of cancer cells could combat chemotherapy-/radiotherapy-resistant tumors. However, the combination of chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and PTT poses another clinical challenge, as it exposes the patient to a higher level of toxicity [24]. Such a challenge could be overcome with nanoparticles to achieve chemo-radiotherapy and PTT. This is due to the nanoparticle ability to preferentially accumulate at the tumor site due to the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect, thereby leaving normal tissues with tightly junctioned blood vessels more or less void of nanoparticles [30]. Figure 1 summarizes the different shapes, surface engineering, functionalization moieties, and some common theragnostic applications of GNPs.

Figure 1. GNP hybrid nanostructures shapes, functionalization, and common applications.

Despite the extensive advances in utilizing nanomaterials, including GNPs, for biomedical applications, individual nanomaterials still suffer from limitations of their own. For instance, systematically administered PTT materials such as inorganic nanoparticles tend to accumulate mostly in the liver and spleen rather than at the tumor site, thereby limiting their therapeutic effectivity. When administered directly to the tumor site to avoid liver and spleen accumulation, nanomaterials are prone to be rapidly cleared up due to their small size. Additionally, cancer treatment usually requires multiple, repeated treatments, which could be difficult with such rapidly cleared, unretained nanoparticles. Furthermore, those inorganic PTT nanomaterials are usually nondegradable [31]. To overcome such limitations, one well-developed strategy is the hybridization of nanomaterials to develop nanostructures with combined advantages and/or compensated weaknesses. Such hybridized nanocomposites are designed to have a performance surpassing that of their individual components [32]. Among these are GNP nanohybrids, which are rapidly emerging as promising candidates for cancer therapy via dual PTT and the triggered delivery of chemotherapeutics. Some GNP hybrid nanostructures were reported to prolong circulation time and increase their cellular internalization rate compared with conventional GNPs, thus achieving more effective and specific delivery of the carried drugs [33]. Furthermore, GNP nanohybrids can also achieve thermoresponsive drug release when combined with a heat-sensitive nanocarrier [34][35][36].

GNPs hybridized with stimuli-sensitive nanocarriers for triggered drug release, individually or combined with other approaches for synergistic (e.g., combined chemotherapy and hyperthermia), multimodal tumor cell ablation, are becoming an increasingly explored topic. For example, GNP photothermal conversion abilities were combined with nanocarriers that responded to heat and other conditions of the tumor microenvironment (TME) [37]. Such unique conditions (e.g., low pH) in a hybrid nanostructure allow a higher degree of tumor-specificity and improved cancer treatment to be obtained [38][39].

2. Smart Drug Delivery Nanocarriers

Several treatment strategies have been developed to combat the disease, including the most commonly utilized approach, chemotherapy. However, despite the advances achieved, cancer therapeutics still possess major limitations that restrict their use. Therefore, interest has shifted towards exploiting nano-based approaches, which hold the potential to overcome those limitations [40]. Chemotherapy is considered one of the most effective cancer treatments available, whether as a single treatment modality or combined with other approaches. However, chemotherapy is limited by its inability to discriminate between cancerous and normal cells, resulting in off-target toxicities [40]. In addition to systematic toxicity, some approved cancer therapeutics also suffer from poor water solubility and a short circulation half-life [41]. Such side effects and limitations can be overcome by trapping the drug within a nanosized carrier capable of carrying the drug through biological barriers to the tumor site and releasing the drug when triggered [41][42][43][44].

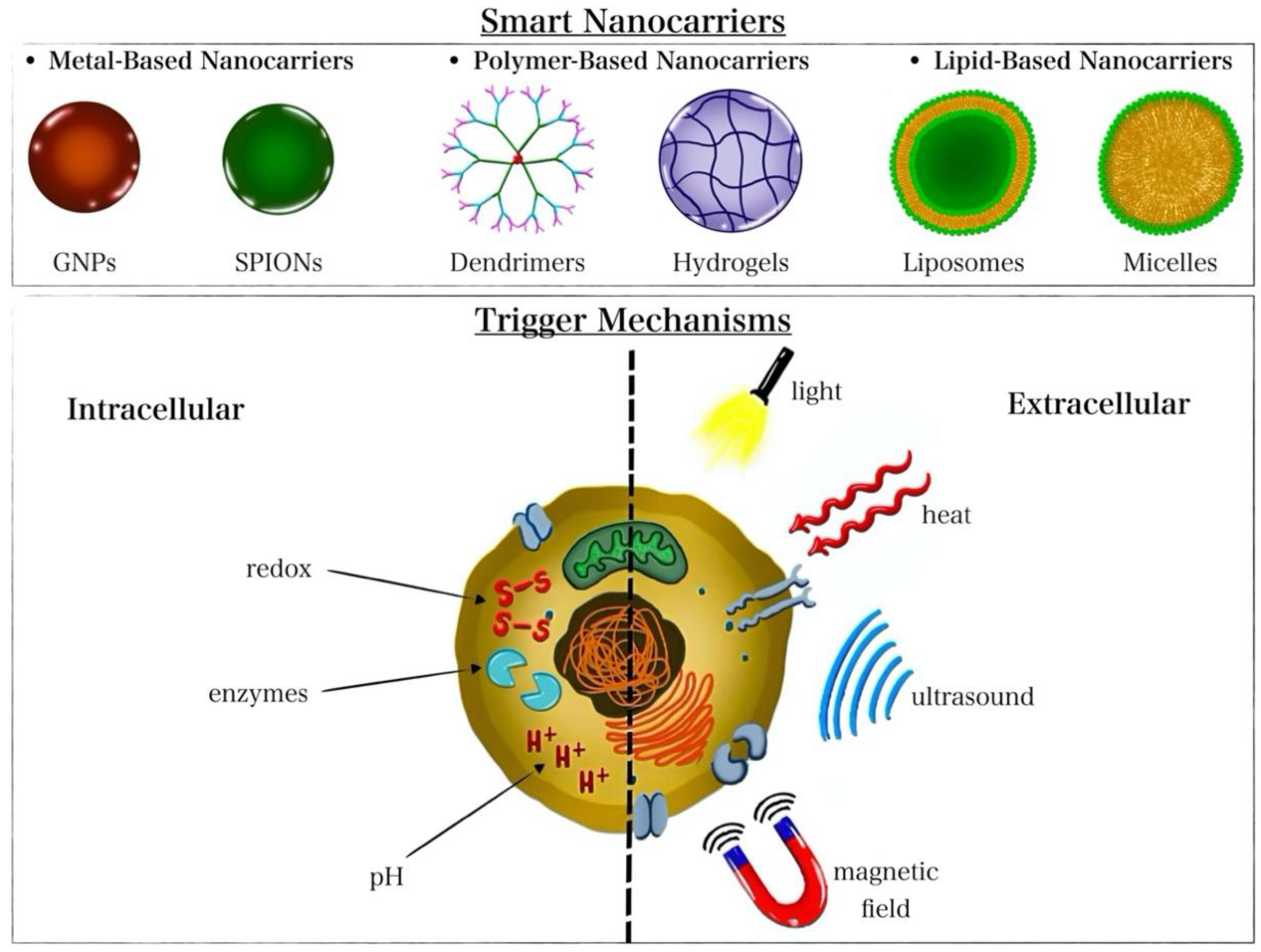

Drug nanocarriers have been developed and studied extensively for cancer therapy using a variety of carriers and drugs. Nanocarriers could be used to allow the delivery of a drug across some of the highly selective biological barriers, such as the blood–brain barrier (BBB) [45]. In addition, several nanocarriers possess stimulus responsiveness due to the structural changes they undergo in response to particular stimuli, such as pH, temperature [46][47], or redox [46], which can be utilized to achieve tailored drug release. Due to their specificity in release, such “smart” nanovehicles for drug delivery purposes have become a widely investigated and reported strategy in the literature [44][45][46][47][48][49].

Some of the most explored nanocarriers for drug delivery purposes are liposomes, micelles, hydrogels, GNPs, iron oxide nanoparticles, carbon-based nanomaterials (e.g., carbon nanotubes), mesoporous nanoparticles, and dendrimers. Different nanocarriers utilize different structures, drug encapsulation mechanisms, and release-triggering stimuli [50][51]. Generally, nanoparticle-mediated delivery enhances drug solubility, bioavailability, stability, and circulation time while reducing its side effects. Broadly, nanocarriers can be divided into metal-based, polymeric, and lipid-based nanocarriers:

- (1)

-

Metal-based nanocarriers are among the emerging materials for biomedicine and drug delivery applications [52]. GNPs and iron oxide nanoparticles (IONPs) have been increasingly studied for drug delivery purposes, as reviewed by Hossen et al. [51]. GNPs and IONPs share the common attractive feature of heat generation that can trigger drug release and/or kill cells via thermal ablation. Both nanoparticles have the benefits of easy synthesis and surface functionalization, [51] and serve as contrast agents to enhance imaging and achieve image-guided therapy [53][54][55]. Additionally, SPIONs exhibit the advantageous property of magnetic targeting via an external magnetic field for spatial targeting [56]. Venditti et al. reported that GNPs are used to improve the bioavailability of drugs [57]. Yet, the practical application of such metal-based nanocarriers can be limited by their potential toxicity [58];

- (2)

-

Polymer-based smart nanocarriers include hydrogels and dendrimers. Dendrimers are large, highly branched polymers capable of loading drugs via entrapment in spaces within the network or by attaching to branching points (via hydrogen bonding or to surface groups via electrostatic interactions) [59][60]. Hydrogels, on the other hand, are composed of hydrophilic crosslinked polymer chains capable of cargo entrapment and delivery [61][62][63]. Dendrimers and hydrogels have been reported for the efficient delivery of genes, drugs, and proteins [64][65][66][67][68][69] and for stimulus-responsive release under various triggers, including temperature, pH, and redox conditions [70][71]. However, dendrimers suffer from their complicated and costly synthesis procedures, and both dendrimers and hydrogels are restricted by their ability to host solely hydrophilic drugs [58];

- (3)

-

Lipid-based nanocarriers include liposomes and micelles. Liposomes, membrane-like self-assembled lipid bilayers, are utilized for the delivery of hydrophobic/hydrophilic drugs, genes, and proteins while possessing high biocompatibility and stimulus responsiveness (e.g., ultrasound and temperature responsiveness) [72]. Micelles are organic nanocarriers similar in structure to liposomes but made up of a single layer. Unlike liposomes, micelles can also be composed of amphiphilic polymers [73][74]. Micelles are used to transport hydrophobic drugs, genes, and proteins and exhibit stimulus responsiveness making them “smart” nanocarriers [75][76]. Liposomes are limited by their poor stability and possibility of triggering an immune response, while micelles are limited by their occasional cytotoxicity and degradability [58]. Several triggering mechanisms can be used to stimulate the release of encapsulated cargo from the nanocarriers [77]. The different types of nanocarriers and possible release trigger mechanisms are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Illustration of the different nanocarrier types and release-triggering mechanisms.

Figure 2. Illustration of the different nanocarrier types and release-triggering mechanisms.

3. Organic GNP Nanohybrid Chemotherapeutic Platforms

3.1. Multimodal Liposome–GNP Nanohybrids

The temperature responsiveness of some nanocarriers, such as liposomes and polymers, makes them suitable vehicles to be hybridized with heat-generating nanomaterials, such as GNPs [46][47]. Several studies explored hybridizing GNPs with thermosensitive nanocarriers to achieve combined hyperthermia-triggered drug release and the thermal ablation of tumor cells [34][38][39][78][79][80][81]. Likewise, some nanocarriers can respond to internal stimuli such as the TME acidic pH [38][39][79], thereby allowing the utilization of multiple stimuli to trigger drug release. One of the materials investigated for GNP hybridization due to their heat responsiveness is liposomes [34][38][39][78][79][80][81]. Liposomes [82] have greatly impacted drug delivery applications by improving the stability, cellular uptake, biodistribution, and biocompatibility of several drugs. Since the first focus on their clinical potential in the 1980s, liposomes have been used to encapsulate hydrophilic and hydrophobic drugs, nucleic acids, proteins, and imaging probes. Advances in liposome-mediated drug delivery were covered by Sercombe et al. [83] and O. B. Olusanya [84]. Low-temperature-sensitive liposomes (LTSLs) capable of undergoing phase transition at low temperatures serve as ideal temperature-responsive carriers due to their ability to respond to mild hyperthermia, which is harmless to normal tissues [78]. LTSLs are used to deliver drugs via mild hyperthermia, such as phase III FDA-approved ThermoDox®, which uses LSTLs to deliver DOX [85]. Despite their numerous advantages, liposomes still suffer from some drawbacks, including their poor drug release and low retention time at the tumor site, which reduce the efficacy of the treatment [86]. GNP–liposome nanohybrids could improve drug release and, thus, therapeutic efficacy.

Koga et al. studied liposome–GNP nanohybrids for the delivery of chemotherapeutic drug doxorubicin (DOX) as a potential strategy to overcome limitations associated with FDA-approved nanoformulation Doxil® (PEGylated liposomal DOX) [34]. Doxil®’s prolonged circulation time due to the presence of PEG is known to cause palmar–plantar erythrodysesthesia, an adverse dermatological skin reaction caused by certain chemotherapeutic drugs [87]. Furthermore, Doxil® was found to utilize the endocytic pathway to enter the cell, which leads to the lysosomal sequestration of the nanocomposite, which could prevent DOX from entering into the nucleus [88], its main site of cytotoxic action [89]. To overcome those limitations, Koga et al. covalently coated thermosensitive PEGylated liposomal DOX with a surface gold nanoshell to achieve a temperature-triggered release of DOX. This study reported the effective gold-nanoshell conversion of NIR light to heat, the induction of heat-induced liposomal phase transition and subsequent DOX release, the biocompatibility of the nanocomposite, and a significantly enhanced eradication of tumor cells via synergistic DOX/hyperthermia effects compared with single DOX or single hyperthermia treatments in vitro. Although the work by Koga et al. claimed to improve the bioavailability of DOX using the GNP-coated thermoresponsive liposomes, the researchers failed to describe the mechanism by which incorporating GNP into Doxil® could avoid lysosomal sequestration [34]. GNP/DOX-loaded liposomes could possibly evade lysosomal entrapment by (1) rupturing the lysosome upon photothermal conversion or (2) causing the heat-triggered release of DOX outside of the cancer cells, thereby making DOX available for all cancer cells at that site. Synergistic PTT/chemotherapy delivery using thermosensitive liposomal GNPs was also studied by Xing et al. [38]. Interestingly, this work utilized two stimuli, heat and low TME-characteristic pH, to trigger DOX release. Xing et al. reported high NIR-to-heat conversion efficiency and successful DOX release via dual heat-induced liposomal phase transition and low-pH-induced membrane instability. Importantly, the GNP–liposome nanohybrid exhibited superior cytotoxicity in vitro and in vivo due to the synergistic PTT–chemotherapy activity while causing negligible systematic toxicity in vivo [38].

Another work by Thakur et al. [90] exploited GNP-incorporated thermosensitive liposomes but delivered a photosensitizer rather than a drug to achieve combined photodynamic therapy (PDT) and PTT. In addition to combining PDT and PTT, this strategy could overcome the limitation of hydrophobicity associated with fluorescent PDT photosensitizer zinc phthalocyanine (ZnPc) by shielding it within liposomes. The GNP-encapsulated ZnPc liposomes showed the efficient entrapment of ZnPc, stability under storage and physiologic conditions, and effective photothermal conversion ability that efficiently triggered ZnPc release. In addition, the nanohybrid retained ZnPc-characteristic fluorescence, efficiently generated singlet oxygen for PDT, and significantly improved internalization and cancer cell growth inhibition in vitro, which substantially inhibited tumor growth due to PDT/PTT synergism [90]. Although this nanohybrid was not used to deliver drugs, it still has the potential to carry and deliver anti-cancer drugs with ZnPc, thereby combining the cytotoxic effects of the delivered drug, PDT, and PTT in a single composite. In addition to tumor annihilation, the fluorescent properties of this nanohybrid could make possible its future utilization for diagnosis or image-guided multimodal delivery/PDT/PTT.

Furthermore, gold nanomaterials were reported to improve PDT by several papers [91][92][93], further extending their potential for PDT therapy and combination with other approaches, such as PTT. Kautzka et al. delivered both a photosensitizer (Rose Bengal) and a chemotherapeutic drug (DOX) using NIR light stimulus for dual enhanced PDT and chemotherapy toxicity. This work reported an improved GNP-induced generation of singlet oxygen species and PDT/chemotherapy cell death in vitro. However, the maximum cell death reported did not exceed 38%. This could have been due to the insufficient heat generated to induce liposomal phase transition (45 °C) at the chosen NIR wavelength [94]. Ou et al. [78] co-delivered LSTL-encapsulated DOX and multi-branched gold nanoantennas (MGNs) for combined heat-triggered DOX delivery and PTT in triple-negative breast cancer in vitro. The co-delivered MGNs and DOX-LSTLs achieved efficient cellular internalization and induced significant cell death in vitro due to NIR-induced heat generation from MGNs and resulting DOX release from LSTLs. Therefore, this study achieved a light-activated, controlled drug delivery that could evade the typical DOX-associated off-target toxicities [78].

Another study by Won et al. improved liposome–GNP nanohybrid drug delivery within a chitosan hydrogel as a reservoir to retain the nanocomposite in the TME [86]. Chitosan was used as a reservoir system due to its ability to undergo a solid–gel phase transition in response to temperature. Importantly, chitosan is a biocompatible and biodegradable polymer with low toxicity and immune response. The researchers reported significant improvement in nanohybrid localization and retention at the tumor site, efficient and sustained heat generation in response to NIR with subsequent DOX release, and significant inhibition of tumor growth while maintaining a good systematic safety profile [86]. In a similar work, Wang et al. utilized chitosan-modified liposomes coated with a gold nanoshell for combined PTT and dual pH/temperature resveratrol (anti-cancer drug) release. The results showed efficient heat generation by the gold nanoshell surpassing that reported for gold nanostars or nanorods and enhanced pH responsiveness due to the presence of amine groups on chitosan. Moreover, increased temperature responsiveness due to the presence of the thermosensitive liposomes was observed, supported by the enhanced resveratrol release in response to the dual pH/temperature stimuli. In vitro analyses showed efficient cellular uptake enhanced by NIR and improved cell death due to resveratrol and PTT synergy [39]. Similarly, Luo et al. utilized GNP–liposome nanohybrids with chitosan for dual pH/temperature oleanolic acid (anti-cancer drug) release. The study reported efficient low-pH- and heat-triggered oleanolic acid release and enhanced chemo-photothermal killing of cancerous cells compared with single chemotherapy or photothermal therapy in vitro and in vivo [79].

Unlike most studies that conjugate GNPs to the liposomal surface, He et al. encapsulated DOX-loaded gold nanocages within thermosensitive liposomes. The liposomal coating was used to improve the stability and biocompatibility of the GNPs. The study showed that coating the GNPs with liposomes and loading DOX did not influence the gold nanocages’ photothermal properties but increased their cellular uptake and nuclear localization. The conversion of NIR light to heat efficiently triggered DOX release due to the liposomes’ phase transition and induced significant tumor cell eradication via hyperthermia/DOX synergy in vitro [80]. In a study by Singh et al., nanogold-coated liposomes were similarly used to load the anti-cancer drug curcumin [95]. The study reported high curcumin loading efficiency, efficient conversion of NIR light to heat, dual PTT- and hyperthermia-triggered curcumin release, significant enhancement in cellular uptake, and in vitro PTT-/curcumin-induced cell death [95]. Several other similar studies utilized liposome–GNP nanohybrids for the delivery of different drugs to improve their bioavailability (e.g., poorly water-soluble betulinic acid), avoid systematic side effects (e.g., DOX), and essentially achieve enhanced tumor annihilation [79][96][97][98][99][100][101].

Another study by Li et al. utilized immune-targeted GNP-coated liposomes modified with a HER-2 antibody to deliver the drug cyclopamine, a drug capable of stroma destruction and tumor cell eradication [102]. The proposed nanoformulation was reported to induce significant toxicity against tumor cells in vitro and in vivo, due to combined chemotherapy/PTT and deep tumor penetration compared with single chemotherapy or PTT treatments. Additionally, HER2 surface modification increased the cellular uptake of the drug-loaded nanocomposite in vitro and in vivo. Notably, the nanocomposite maintained a good safety profile in vivo [102].

Another strategy explored by Zhang et al. used ammonium bicarbonate (ABC)- and DOX-encapsulated liposomal gold nanorods (GNRs) for image-guided, NIR-triggered drug release. Upon exposure to NIR light, ABC decomposes and generates carbon dioxide, causing transient cavitation that can promote DOX release. The DOX/ABC-loaded liposomal GNRs were also decorated with folic acid to achieve tumor targeting. Furthermore, GNRs were also used as CT contrast agents to achieve image-guided chemotherapy delivery to tumor cells. In vitro and in vivo studies served as good CT contrast agents and showed increased tumor inhibition upon NIR exposure compared with ABC-lacking composites [103]. On the other hand, Rengan et al. developed thermosensitive GNP-modified liposomes for hyperthermia-triggered drug release, PTT, and CT imaging. The results showed efficient PTT and PTT-induced cell death in vitro, the heat-triggered release of the model drug/dye calcein, and CT contrast of the GNP liposomes [104].

In addition to solid GNPs, thermoresponsive liposomes were also studied with hollow GNPs (HGNPs). HGNPs gained attention over solid GNPs, particularly for drug delivery purposes, due to the presence of an inner cavity capable of drug hosting and possessing higher photothermal conversion abilities [81]. Similar to solid GNPs, HGNPs come in different morphologies, such as spheres, rods, stars, and cages. Their use for biomedical applications was reviewed by Park et al. [105]. Several studies explored bare HGNPs to encapsulate drugs and achieve heat-triggered drug release with/without PTT, as reported by You et al. [106] and Xiong et al. [107]. Those studies incorporated groups that can be cleaved via heat generation, such as surface peptides linked to GNPs through Au-S bonds [107]. A study that compared solid GNP–liposome nanohybrids with hollow GNP–liposome nanohybrids reported an eight-fold enhancement of anticancer activity from chemotherapy–hyperthermia coaction using hollow GNP-loaded liposomes [81].

Other studies explored liposome–GNP nanohybrids as drug carriers without the use of triggering stimuli or stimuli other than temperature [41][108][109][110][111][112]. Sonkar et al. [108] reported the use of transferrin-coated liposomes encapsulating chemotherapy docetaxel and GNPs. This transferrin-targeted nanoformulation achieved sustained docetaxel release, a higher tumor cell eradication at a lower concentration compared with the marketed docetaxel, and higher cellular uptake compared with their non-targeted counterparts. Although this work did not benefit from photothermal conversion, this nanoformulation could be further modified by utilizing thermoresponsive delivery and dual chemotherapy/PTT actions for multimodal therapy [108]. Hamzawy et al. delivered the drug temozolomide via intratracheal inhalation using GNP–liposome hybrids as nanocarriers. The nanocomposite showed improved in vivo drug delivery while avoiding systematic toxicity [111]. Another study by Zhang et al. delivered PTX from GNP–liposome nanohybrids via diffusion, glutathione (GSH)-induced release, and enzyme-mediated release [110]. GSH is a commonly upregulated antioxidant in cancers to counteract oxidative stresses [113]. Therefore, GSH provides a tumor-specific endogenous stimulus for drug delivery purposes [114]. Bao et al. [41] also used GNP–liposome hybrids to deliver chemotherapeutic drug paclitaxel using the enzyme esterase and the antioxidant GSH as triggers. This study reported sustained intracellular paclitaxel release, improved blood circulation time, and enhanced anti-cancer activity in vivo [41]. Furthermore, liposomal GNPs were also used to deliver genes in addition to drugs without utilizing GNPs for heat-related effects (PTT or heat-triggered release) or radiotherapy [112].

GNP–liposome nanohybrids were also explored for single PTT or hyperthermia-triggered drug release. PEG-coated liposomal GNPs were studied for single PTT and were found to exhibit enhanced PTT, cell cytotoxicity, and passive targeting abilities in vivo [115]. Likewise, Kwon et al. released DOX from GNP–liposome hybrid nanostructures using NIR-generated heat and reported efficient DOX encapsulation and NIR-triggered release compared with GNP-negative thermosensitive liposomes. As a result, the nanocomposite induced tumor growth inhibition in vitro and in vivo upon DOX loading and NIR exposure [116].

Other liposome–GNP nanohybrids were used for the triggered delivery of proteins and genes, as reported by Du et al. [117], Refaat et al. [118], and Grafals-Ruiz [119]. Gene therapy is one of the promising strategies explored for cancer treatment in which genes are either: (1) provided to translate to a disease-curing protein [117] or (2) delivered to cells to regulate the expression of certain genes [117][120]. RNA interference is a commonly used type of gene therapy that involves the use of an RNA molecule to knock down a target gene. Small interfering RNA (siRNA) was studied for such inhibition of genes by targeting messenger RNAs. Although promising, treatment via siRNA is greatly limited by RNA instability and susceptibility to degradation.

Jia et al. [120] used liposomal GNPs to deliver siRNA to the mutant oncogene K-Ras in vitro and in vivo for dual siRNA and PTT tumor eradication. A photothermal nanomaterial, Prussian blue analog (PBA), gold nanoflowers, targeting RGD peptides, and liposomes were incorporated into a single composite to achieve dual NIR-triggered siRNA release and PTT (gene therapy–PTT synergy). This composite could achieve gene therapy–PTT coaction guided by three imaging modalities: CT imaging, photoacoustic imaging (PAI), and photothermal imaging (PTI). Owing to the synergism between the components of the nanohybrid, it achieved increased accumulation at the tumor site, significant siRNA-induced inhibition of K-Ras expression, and significant inhibition of tumor cell growth in vitro and in vivo upon NIR exposure. In terms of imaging abilities, the nanohybrid improved PAI, PTI, and CT imaging, thereby indicating the composites’ potential for image-guided therapy [120]. Liposomal GNPs were also used to deliver interfering RNAs (RNAi) across highly selective biological barriers, such as the BBB. Grafals-Ruiz et al. used RNAi-functionalized GNPs entrapped within liposomes and targeted via BBB-targeting peptides for glioblastoma treatment. This study reported efficient cellular internalization and the inhibition of the overexpressed microRNA (miRNA-92b) involved in glioblastoma growth and progression, both in vitro and in vivo. However, this study did not benefit from any triggering stimulus to control the release of RNAi [119]. Likewise, liposomal GNPs were exploited for the delivery of both nucleotides and drugs. Skalickova et al. encapsulated fluorescent drugs (DOX, ellipticine, and/or etoposide) and the antisense oligonucleotide that can block the N-myc protooncogene. The formulations demonstrated the suitability of the liposomal gold nanoparticles for delivering both drugs and oligonucleotides. However, this study did not employ any triggering mechanism and did not assess the biocompatibility or the tumor-killing ability of the nanohybrid in vitro or in vivo [121].

Other studies utilized GNP–liposome nanohybrids but did not benefit from the GNP photothermal properties for triggered drug release or thermal ablation. However, the incorporation of GNPs into those nanocomposites suggests their possible future utilization for photothermal conversion. Liposome-coated GNP nanohybrids loaded with the antimitotic drug docetaxel (DTX) were studied by Kang et al. The results showed efficient entrapment of DTX within the lipid bilayer, controlled untriggered DTX release, increased cellular uptake and significant toxicity surpassing that of the free drug in vitro [122]. Another study by Kunjiappan et al. also exploited liposome–GNP nanohybrids to deliver epirubicin, a chemotherapeutic agent targeting lymph-node-metastasized breast cancer, and reported similar satisfactory results [123].

3.2. Multimodal Polymer–GNP Nanohybrids

Polymeric nanocarriers are another group of smart nanovehicles that can improve the performance of traditional cancer therapeutics [124][125]. These polymeric drug delivery systems can be further modified to induce stimulus responsiveness and improve their performance [125]. Chitosan alginates and deoxyribonucleic acid are interesting natural polymeric nanocarriers for drug delivery purposes due to their natural biocompatibility, stimulus responsiveness, and hydrophobic/hydrophilic drug encapsulation [126][127]. For instance, one of the materials that polymers were hybridized with is GNPs. Zhang et al. functionalized the GNP surface with DNA and an affibody (HER2-specific antibody mimetic) to provide HER2 targeting to tumor cells for 5-fluorouracil and DOX co-delivery. Interestingly, this work reported the effective loading of both drugs and acidic pH- and DNase II (nuclease)-triggered drug release [128]. Low pH and high DNase II expression levels are both tumor-specific features that can ensure drug release specifically at the tumor site [37][129]. Furthermore, the internalization rate of the drug-loaded GNP nanohybrids of HER2-overexpressing cancer cells increased due to affibody-receptor-mediated endocytosis in vitro. In vitro studies also showed the biocompatibility of nanohybrids and improved cytotoxic effects surpassing those of the free drug combination in HER2-overexpressing breast cancer cells due to DOX/5–fluorouracil synergy and affibody-mediated internalization [128].

Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA), another smart polymeric nanocarrier, was explored as a thermosensitive drug carrier for combined heat-induced drug delivery and PTT. Park et al. utilized DOX-loaded PLGA, half-coated with GNPs, for dual chemotherapy delivery and PTT. The formulation exhibited high biocompatibility, enhanced cytotoxicity compared with single DOX or single PTT treatments due to DOX/PTT synergy, and the effective internalization of the nanohybrid in vitro [130]. Another polymeric GNP hybrid investigated by Adeli et al. used polyrotaxanes to shelter GNPs for heat-triggered DOX and cisplatin release. Polyrotaxanes are highly functional and biocompatible assemblies of α-cylodextrin rings supramolecularly anchored to PEG axes that can improve the internalization rate of nanocomposites of tumor cells. Light-to-heat conversion by GNPs induced polyrotaxane shell cleavage leading to the effective release of the encapsulated drugs and induced cytotoxicity comparable to that of free drugs while maintaining compatibility in vitro. However, even though the nanohybrid successfully induced the death of cancer cells, the viability of the cells was not reduced below ~40% for DOX and ~50% for cisplatin, respectively [33]. The GNP/polyrotaxane nanohybrid’s cytotoxic effects could be intensified by combining the heat-induced drug release with photothermal therapy, radiotherapy, or maybe both.

Other GNP polymeric nanohybrids were studied without utilizing the GNP photothermal properties for triggered drug release, thermal ablation, or radiotherapy. Dai et al. [131] hybridized GNPs with protein polymers to endue the nanocomposite with biocompatibility and improve the uptake of the hydrophobic drug curcumin. A significant enhancement in the GNP/protein polymer binding and the in vitro cellular uptake of the drug curcumin were observed. Moreover, curcumin exhibited a sustained release profile compared with GNP-free protein polymers. However, this study did not assess the toxicity of this system against cancer cells [131]. Future improvements in this hybrid nanostructure could be obtained by utilizing other GNP features, such as photothermal conversion effects.

References

- Sibuyi, N.R.S.; Moabelo, K.L.; Fadaka, A.O.; Meyer, S.; Onani, M.O.; Madiehe, A.M.; Meyer, M. Multifunctional Gold Nanoparticles for Improved Diagnostic and Therapeutic Applications: A Review. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 174.

- Kong, F.-Y.; Zhang, J.-W.; Li, R.-F.; Wang, Z.-X.; Wang, W.-J.; Wang, W. Unique Roles of Gold Nanoparticles in Drug Delivery, Targeting and Imaging Applications. Molecules 2017, 22, 1445.

- Tiwari, P.; Vig, K.; Dennis, V.; Singh, S. Functionalized Gold Nanoparticles and Their Biomedical Applications. Nanomaterials 2011, 1, 31–63.

- Chen, X.; Li, Q.W.; Wang, X.M. Gold Nanostructures for Bioimaging, Drug Delivery and Therapeutics. In Precious Metals for Biomedical Applications; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 163–176. ISBN 978-0-85709-434-6.

- Chandran, P.R.; Thomas, R.T. Gold Nanoparticles in Cancer Drug Delivery. In Nanotechnology Applications for Tissue Engineering; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 221–237. ISBN 978-0-323-32889-0.

- Maccora, D.; Dini, V.; Battocchio, C.; Fratoddi, I.; Cartoni, A.; Rotili, D.; Castagnola, M.; Faccini, R.; Bruno, I.; Scotognella, T.; et al. Gold Nanoparticles and Nanorods in Nuclear Medicine: A Mini Review. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 3232.

- Rai, M.; Yadav, A. (Eds.) Nanobiotechnology in Neurodegenerative Diseases; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; ISBN 978-3-030-30929-9.

- Rodzik-Czałka, Ł.; Lewandowska-Łańcucka, J.; Gatta, V.; Venditti, I.; Fratoddi, I.; Szuwarzyński, M.; Romek, M.; Nowakowska, M. Nucleobases Functionalized Quantum Dots and Gold Nanoparticles Bioconjugates as a Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) System—Synthesis, Characterization and Potential Applications. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2018, 514, 479–490.

- Vines, J.B.; Yoon, J.-H.; Ryu, N.-E.; Lim, D.-J.; Park, H. Gold Nanoparticles for Photothermal Cancer Therapy. Front. Chem. 2019, 7, 167.

- Sztandera, K.; Gorzkiewicz, M.; Klajnert-Maculewicz, B. Gold Nanoparticles in Cancer Treatment. Mol. Pharm. 2019, 16, 1–23.

- Huang, X.; El-Sayed, M.A. Gold Nanoparticles: Optical Properties and Implementations in Cancer Diagnosis and Photothermal Therapy. J. Adv. Res. 2010, 1, 13–28.

- Hu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Ding, T.; Liu, J.; Zhao, H. Multifunctional Gold Nanoparticles: A Novel Nanomaterial for Various Medical Applications and Biological Activities. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 990.

- Yu, C.; Xu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Timashev, P.S.; Huang, Y.; Liang, X.-J. Polymer-Based Nanomaterials for Noninvasive Cancer Photothermal Therapy. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2020, 2, 4289–4305.

- Behrouzkia, Z.; Joveini, Z.; Keshavarzi, B.; Eyvazzadeh, N.; Aghdam, R.Z. Hyperthermia: How Can It Be Used? Oman Med. J. 2016, 31, 89–97.

- Dunne, M.; Regenold, M.; Allen, C. Hyperthermia Can Alter Tumor Physiology and Improve Chemo- and Radio-Therapy Efficacy. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2020, 163–164, 98–124.

- Beik, J.; Abed, Z.; Ghoreishi, F.S.; Hosseini-Nami, S.; Mehrzadi, S.; Shakeri-Zadeh, A.; Kamrava, S.K. Nanotechnology in Hyperthermia Cancer Therapy: From Fundamental Principles to Advanced Applications. J. Control. Release 2016, 235, 205–221.

- Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, W.; Li, G.; Ma, X.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, S.; Tiwari, S.; Shi, K.; et al. Comprehensive Understanding of Magnetic Hyperthermia for Improving Antitumor Therapeutic Efficacy. Theranostics 2020, 10, 3793–3815.

- Petryk, A.A.; Giustini, A.J.; Gottesman, R.E.; Kaufman, P.A.; Hoopes, P.J. Magnetic Nanoparticle Hyperthermia Enhancement of Cisplatin Chemotherapy Cancer Treatment. Int. J. Hyperth. 2013, 29, 845–851.

- Najahi-Missaoui, W.; Arnold, R.D.; Cummings, B.S. Safe Nanoparticles: Are We There Yet? IJMS 2020, 22, 385.

- Jia, Y.-P.; Ma, B.-Y.; Wei, X.-W.; Qian, Z.-Y. The in Vitro and in Vivo Toxicity of Gold Nanoparticles. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2017, 28, 691–702.

- Singh, A.K.; Srivastava, O.N. One-Step Green Synthesis of Gold Nanoparticles Using Black Cardamom and Effect of PH on Its Synthesis. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2015, 10, 353.

- Yang, W.; Xia, B.; Wang, L.; Ma, S.; Liang, H.; Wang, D.; Huang, J. Shape Effects of Gold Nanoparticles in Photothermal Cancer Therapy. Mater. Today Sustain. 2021, 13, 100078.

- Chithrani, B.D.; Ghazani, A.A.; Chan, W.C.W. Determining the Size and Shape Dependence of Gold Nanoparticle Uptake into Mammalian Cells. Nano Lett. 2006, 6, 662–668.

- Alamzadeh, Z.; Beik, J.; Mirrahimi, M.; Shakeri-Zadeh, A.; Ebrahimi, F.; Komeili, A.; Ghalandari, B.; Ghaznavi, H.; Kamrava, S.K.; Moustakis, C. Gold Nanoparticles Promote a Multimodal Synergistic Cancer Therapy Strategy by Co-Delivery of Thermo-Chemo-Radio Therapy. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 145, 105235.

- Keshavarz, M.; Moloudi, K.; Paydar, R.; Abed, Z.; Beik, J.; Ghaznavi, H.; Shakeri-Zadeh, A. Alginate Hydrogel Co-Loaded with Cisplatin and Gold Nanoparticles for Computed Tomography Image-Guided Chemotherapy. J. Biomater. Appl. 2018, 33, 161–169.

- Hainfeld, J.F.; Dilmanian, F.A.; Zhong, Z.; Slatkin, D.N.; Kalef-Ezra, J.A.; Smilowitz, H.M. Gold Nanoparticles Enhance the Radiation Therapy of a Murine Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Phys. Med. Biol. 2010, 55, 3045–3059.

- Piccolo, O.; Lincoln, J.D.; Melong, N.; Orr, B.C.; Fernandez, N.R.; Borsavage, J.; Berman, J.N.; Robar, J.; Ha, M.N. Radiation Dose Enhancement Using Gold Nanoparticles with a Diamond Linear Accelerator Target: A Multiple Cell Type Analysis. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1559.

- Popovtzer, R.; Agrawal, A.; Kotov, N.A.; Popovtzer, A.; Balter, J.; Carey, T.E.; Kopelman, R. Targeted Gold Nanoparticles Enable Molecular CT Imaging of Cancer. Nano Lett. 2008, 8, 4593–4596.

- Chemla, Y.; Betzer, O.; Markus, A.; Farah, N.; Motiei, M.; Popovtzer, R.; Mandel, Y. Gold Nanoparticles for Multimodal High-Resolution Imaging of Transplanted Cells for Retinal Replacement Therapy. Nanomedicine 2019, 14, 1857–1871.

- Mirrahimi, M.; Khateri, M.; Beik, J.; Ghoreishi, F.S.; Dezfuli, A.S.; Ghaznavi, H.; Shakeri-Zadeh, A. Enhancement of Chemoradiation by Co-incorporation of Gold Nanoparticles and Cisplatin into Alginate Hydrogel. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2019, 107, 2658–2663.

- Hsiao, C.-W.; Chuang, E.-Y.; Chen, H.-L.; Wan, D.; Korupalli, C.; Liao, Z.-X.; Chiu, Y.-L.; Chia, W.-T.; Lin, K.-J.; Sung, H.-W. Photothermal Tumor Ablation in Mice with Repeated Therapy Sessions Using NIR-Absorbing Micellar Hydrogels Formed in Situ. Biomaterials 2015, 56, 26–35.

- Tan, C.; Chen, J.; Wu, X.-J.; Zhang, H. Epitaxial Growth of Hybrid Nanostructures. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2018, 3, 17089.

- Adeli, M.; Sarabi, R.S.; Yadollahi Farsi, R.; Mahmoudi, M.; Kalantari, M. Polyrotaxane/Gold Nanoparticle Hybrid Nanomaterials as Anticancer Drug Delivery Systems. J. Mater. Chem. 2011, 21, 18686.

- Koga, K.; Tagami, T.; Ozeki, T. Gold Nanoparticle-Coated Thermosensitive Liposomes for the Triggered Release of Doxorubicin, and Photothermal Therapy Using a near-Infrared Laser. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2021, 626, 127038.

- Howaili, F.; Özliseli, E.; Küçüktürkmen, B.; Razavi, S.M.; Sadeghizadeh, M.; Rosenholm, J.M. Stimuli-Responsive, Plasmonic Nanogel for Dual Delivery of Curcumin and Photothermal Therapy for Cancer Treatment. Front. Chem. 2021, 8, 602941.

- Pourjavadi, A.; Doroudian, M.; Bagherifard, M.; Bahmanpour, M. Magnetic and Light-Responsive Nanogels Based on Chitosan Functionalized with Au Nanoparticles and Poly(N-Isopropylacrylamide) as a Remotely Triggered Drug Carrier. New J. Chem. 2020, 44, 17302–17312.

- Yang, L. Tumor Microenvironment and Metabolism. IJMS 2017, 18, 2729.

- Xing, S.; Zhang, X.; Luo, L.; Cao, W.; Li, L.; He, Y.; An, J.; Gao, D. Doxorubicin/Gold Nanoparticles Coated with Liposomes for Chemo-Photothermal Synergetic Antitumor Therapy. Nanotechnology 2018, 29, 405101.

- Wang, M.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Luo, L.; Li, L.; Xing, S.; He, Y.; Cao, W.; Zhu, R.; Gao, D. Gold Nanoshell Coated Thermo-PH Dual Responsive Liposomes for Resveratrol Delivery and Chemo-Photothermal Synergistic Cancer Therapy. J. Mater. Chem. B 2017, 4, 1–12.

- Debela, D.T.; Muzazu, S.G.; Heraro, K.D.; Ndalama, M.T.; Mesele, B.W.; Haile, D.C.; Kitui, S.K.; Manyazewal, T. New Approaches and Procedures for Cancer Treatment: Current Perspectives. SAGE Open Med. 2021, 9, 20503121211034366.

- Bao, Q.-Y.; Zhang, N.; Geng, D.-D.; Xue, J.-W.; Merritt, M.; Zhang, C.; Ding, Y. The Enhanced Longevity and Liver Targetability of Paclitaxel by Hybrid Liposomes Encapsulating Paclitaxel-Conjugated Gold Nanoparticles. Int. J. Pharm. 2014, 477, 408–415.

- Wang, W.; Shao, A.; Zhang, N.; Fang, J.; Ruan, J.J.; Ruan, B.H. Cationic Polymethacrylate-Modified Liposomes Significantly Enhanced Doxorubicin Delivery and Antitumor Activity. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 43036.

- Chowdhury, N.; Chaudhry, S.; Hall, N.; Olverson, G.; Zhang, Q.-J.; Mandal, T.; Dash, S.; Kundu, A. Targeted Delivery of Doxorubicin Liposomes for Her-2+ Breast Cancer Treatment. AAPS Pharm. Sci. Tech. 2020, 21, 202.

- Zhang, X.; Zhu, T.; Miao, Y.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, W. Dual-Responsive Doxorubicin-Loaded Nanomicelles for Enhanced Cancer Therapy. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2020, 18, 136.

- Norouzi, M.; Yathindranath, V.; Thliveris, J.A.; Kopec, B.M.; Siahaan, T.J.; Miller, D.W. Doxorubicin-Loaded Iron Oxide Nanoparticles for Glioblastoma Therapy: A Combinational Approach for Enhanced Delivery of Nanoparticles. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 11292.

- An, X. Stimuli-Responsive Liposome and Control Release Drug; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; Volume 31.

- Wang, D.; Green, M.D.; Chen, K.; Daengngam, C.; Kotsuchibashi, Y. Stimuli-Responsive Polymers: Design, Synthesis, Characterization, and Applications. Int. J. Polym. Sci. 2016, 2016, 6480259.

- Ortega-García, A.; Martínez-Bernal, B.G.; Ceja, I.; Mendizábal, E.; Puig-Arévalo, J.E.; Pérez-Carrillo, L.A. Drug Delivery from Stimuli-Responsive Poly(N-Isopropylacrylamide-Co-N-Isopropylmethacrylamide)/Chitosan Core/Shell Nanohydrogels. Polymers 2022, 14, 522.

- Harris, M.; Ahmed, H.; Barr, B.; LeVine, D.; Pace, L.; Mohapatra, A.; Morshed, B.; Bumgardner, J.D.; Jennings, J.A. Magnetic Stimuli-Responsive Chitosan-Based Drug Delivery Biocomposite for Multiple Triggered Release. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 104, 1407–1414.

- Hajebi, S.; Rabiee, N.; Bagherzadeh, M.; Ahmadi, S.; Rabiee, M.; Roghani-Mamaqani, H.; Tahriri, M.; Tayebi, L.; Hamblin, M.R. Stimulus-Responsive Polymeric Nanogels as Smart Drug Delivery Systems. Acta Biomater. 2019, 92, 1–18.

- Hossen, S.; Hossain, M.K.; Basher, M.K.; Mia, M.N.H.; Rahman, M.T.; Uddin, M.J. Smart Nanocarrier-Based Drug Delivery Systems for Cancer Therapy and Toxicity Studies: A Review. J. Adv. Res. 2019, 15, 1–18.

- Venditti, I.; Testa, G.; Sciubba, F.; Carlini, L.; Porcaro, F.; Meneghini, C.; Mobilio, S.; Battocchio, C.; Fratoddi, I. Hydrophilic Metal Nanoparticles Functionalized by 2-Diethylaminoethanethiol: A Close Look at the Metal−Ligand Interaction and Interface Chemical Structure. J. Phys. Chem. C 2017, 121, 8002–8013.

- Yin, X.; Russek, S.E.; Zabow, G.; Sun, F.; Mohapatra, J.; Keenan, K.E.; Boss, M.A.; Zeng, H.; Liu, J.P.; Viert, A.; et al. Large T1 Contrast Enhancement Using Superparamagnetic Nanoparticles in Ultra-Low Field MRI. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 11863.

- Luo, D.; Wang, X.; Burda, C.; Basilion, J.P. Recent Development of Gold Nanoparticles as Contrast Agents for Cancer Diagnosis. Cancers 2021, 13, 1825.

- Fan, M.; Han, Y.; Gao, S.; Yan, H.; Cao, L.; Li, Z.; Liang, X.-J.; Zhang, J. Ultrasmall Gold Nanoparticles in Cancer Diagnosis and Therapy. Theranostics 2020, 10, 4944–4957.

- Fontes de Paula Aguiar, M.; Bustamante Mamani, J.; Klei Felix, T.; Ferreira dos Reis, R.; Rodrigues da Silva, H.; Nucci, L.P.; Nucci-da-Silva, M.P.; Gamarra, L.F. Magnetic Targeting with Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles for In Vivo Glioma. Nanotechnol. Rev. 2017, 6, 449–472.

- Venditti, I.; Iucci, G.; Fratoddi, I.; Cipolletti, M.; Montalesi, E.; Marino, M.; Secchi, V.; Battocchio, C. Direct Conjugation of Resveratrol on Hydrophilic Gold Nanoparticles: Structural and Cytotoxic Studies for Biomedical Applications. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1898.

- AlSawaftah, N.M.; Awad, N.S.; Pitt, W.G.; Husseini, G.A. PH-Responsive Nanocarriers in Cancer Therapy. Polymers 2022, 14, 936.

- Chauhan, A. Dendrimers for Drug Delivery. Molecules 2018, 23, 938.

- Choudhary, S.; Gupta, L.; Rani, S.; Dave, K.; Gupta, U. Impact of Dendrimers on Solubility of Hydrophobic Drug Molecules. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 261.

- de Lima, C.S.A.; Balogh, T.S.; Varca, J.P.R.O.; Varca, G.H.C.; Lugão, A.B.; Camacho-Cruz, L.A.; Bucio, E.; Kadlubowski, S.S. An Updated Review of Macro, Micro, and Nanostructured Hydrogels for Biomedical and Pharmaceutical Applications. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 970.

- Chai, Q.; Jiao, Y.; Yu, X. Hydrogels for Biomedical Applications: Their Characteristics and the Mechanisms behind Them. Gels 2017, 3, 6.

- Kopeček, J.; Yang, J. Hydrogels as Smart Biomaterials. Polym. Int. 2007, 56, 1078–1098.

- Santander-Ortega, M.J.; Lozano, M.V.; Uchegbu, I.F.; Schätzlein, A.G. Dendrimers for Gene Therapy. In Polymers and Nanomaterials for Gene Therapy; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 113–146. ISBN 978-0-08-100520-0.

- Lv, J.; Wang, C.; Li, H.; Li, Z.; Fan, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, H.; Cheng, Y. Bifunctional and Bioreducible Dendrimer Bearing a Fluoroalkyl Tail for Efficient Protein Delivery Both In Vitro and In Vivo. Nano Lett. 2020, 20, 8600–8607.

- Liu, C.; Wan, T.; Wang, H.; Zhang, S.; Ping, Y.; Cheng, Y. A Boronic Acid–Rich Dendrimer with Robust and Unprecedented Efficiency for Cytosolic Protein Delivery and CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Editing. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaaw8922.

- Kandil, R.; Merkel, O.M. Recent Progress of Polymeric Nanogels for Gene Delivery. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2019, 39, 11–23.

- Kousalová, J.; Etrych, T. Polymeric Nanogels as Drug Delivery Systems. Physiol. Res. 2018, 67, S305–S317.

- Xu, X.; Shen, S.; Mo, R. Bioresponsive Nanogels for Protein Delivery. View 2022, 3, 20200136.

- Wang, H.; Huang, Q.; Chang, H.; Xiao, J.; Cheng, Y. Stimuli-Responsive Dendrimers in Drug Delivery. Biomater. Sci. 2016, 4, 375–390.

- Chacko, R.T.; Ventura, J.; Zhuang, J.; Thayumanavan, S. Polymer Nanogels: A Versatile Nanoscopic Drug Delivery Platform. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2012, 64, 836–851.

- Bahutair, W.N.; Abuwatfa, W.H.; Husseini, G.A. Ultrasound Triggering of Liposomal Nanodrugs for Cancer Therapy: A Review. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 3051.

- Hanafy, N.; El-Kemary, M.; Leporatti, S. Micelles Structure Development as a Strategy to Improve Smart Cancer Therapy. Cancers 2018, 10, 238.

- Ghezzi, M.; Pescina, S.; Padula, C.; Santi, P.; Del Favero, E.; Cantù, L.; Nicoli, S. Polymeric Micelles in Drug Delivery: An Insight of the Techniques for Their Characterization and Assessment in Biorelevant Conditions. J. Control. Release 2021, 332, 312–336.

- Jhaveri, A.M.; Torchilin, V.P. Multifunctional Polymeric Micelles for Delivery of Drugs and SiRNA. Front. Pharmacol. 2014, 5, 77.

- Zhou, Q.; Zhang, L.; Yang, T.; Wu, H. Stimuli-Responsive Polymeric Micelles for Drug Delivery and Cancer Therapy. IJN 2018, 13, 2921–2942.

- Mi, P. Stimuli-Responsive Nanocarriers for Drug Delivery, Tumor Imaging, Therapy and Theranostics. Theranostics 2020, 10, 4557–4588.

- Ou, Y.-C.; Webb, J.A.; Faley, S.; Shae, D.; Talbert, E.M.; Lin, S.; Cutright, C.C.; Wilson, J.T.; Bellan, L.M.; Bardhan, R. Gold Nanoantenna-Mediated Photothermal Drug Delivery from Thermosensitive Liposomes in Breast Cancer. ACS Omega 2016, 1, 234–243.

- Luo, L.; Bian, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, M.; Xing, S.; Li, L.; Gao, D. Combined Near Infrared Photothermal Therapy and Chemotherapy Using Gold Nanoshells Coated Liposomes to Enhance Antitumor Effect. Small 2016, 12, 4103–4112.

- He, H.; Liu, L.; Zhang, S.; Zheng, M.; Ma, A.; Chen, Z.; Pan, H.; Zhou, H.; Liang, R.; Cai, L. Smart Gold Nanocages for Mild Heat-Triggered Drug Release and Breaking Chemoresistance. J. Control. Release 2020, 323, 387–397.

- Li, Y.; He, D.; Tu, J.; Wang, R.; Zu, C.; Chen, Y.; Yang, W.; Shi, D.; Webster, T.J.; Shen, Y. Comparative Effect of Wrapping Solid Gold Nanoparticles and Hollow Gold Nanoparticles with Doxorubicin-Loaded Thermosensitive Liposomes for Cancer Thermo-Chemotherapy. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 8628–8641.

- Hossann, M.; Kneidl, B.; Peller, M.; Lindner, L.; Winter, G. Thermosensitive Liposomal Drug Delivery Systems: State of the Art Review. IJN 2014, 9, 4387–4398.

- Sercombe, L.; Veerati, T.; Moheimani, F.; Wu, S.Y.; Sood, A.K.; Hua, S. Advances and Challenges of Liposome Assisted Drug Delivery. Front. Pharmacol. 2015, 6, 286.

- Olusanya, T.; Haj Ahmad, R.; Ibegbu, D.; Smith, J.; Elkordy, A. Liposomal Drug Delivery Systems and Anticancer Drugs. Molecules 2018, 23, 907.

- Bhardwaj, V.; Kaushik, A.; Khatib, Z.M.; Nair, M.; McGoron, A.J. Recalcitrant Issues and New Frontiers in Nano-Pharmacology. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 1369.

- Won, J.E.; Wi, T.I.; Lee, C.M.; Lee, J.H.; Kang, T.H.; Lee, J.-W.; Shin, B.C.; Lee, Y.; Park, Y.-M.; Han, H.D. NIR Irradiation-Controlled Drug Release Utilizing Injectable Hydrogels Containing Gold-Labeled Liposomes for the Treatment of Melanoma Cancer. Acta Biomater. 2021, 136, 508–518.

- Lorusso, D.; Di Stefano, A.; Carone, V.; Fagotti, A.; Pisconti, S.; Scambia, G. Pegylated Liposomal Doxorubicin-Related Palmar-Plantar Erythrodysesthesia (‘Hand-Foot’ Syndrome). Ann. Oncol. 2007, 18, 1159–1164.

- Seynhaeve, A.L.B. Intact Doxil Is Taken up Intracellularly and Released Doxorubicin Sequesters in the Lysosome: Evaluated by in Vitro/in Vivo Live Cell Imaging. J. Control. Release 2013, 172, 330–340.

- Chaikomon, K.; Chattong, S.; Chaiya, T.; Tiwawech, D.; Sritana-anant, Y.; Sereemaspun, A.; Manotham, K. Doxorubicin-Conjugated Dexamethasone Induced MCF-7 Apoptosis without Entering the Nucleus and Able to Overcome MDR-1-Induced Resistance. DDDT 2018, 12, 2361–2369.

- Thakur, N.S.; Patel, G.; Kushwah, V.; Jain, S.; Banerjee, U.C. Self-Assembled Gold Nanoparticle−Lipid Nanocomposites for On- Demand Delivery, Tumor Accumulation, and Combined Photothermal−Photodynamic Therapy. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2019, 2, 349–361.

- Kang, Z.; Yan, X.; Zhao, L.; Liao, Q.; Zhao, K.; Du, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y. Gold Nanoparticle/ZnO Nanorod Hybrids for Enhanced Reactive Oxygen Species Generation and Photodynamic Therapy. Nano Res. 2015, 8, 2004–2014.

- Zhao, T.; Yu, K.; Li, L.; Zhang, T.; Guan, Z.; Gao, N.; Yuan, P.; Li, S.; Yao, S.Q.; Xu, Q.-H.; et al. Gold Nanorod Enhanced Two-Photon Excitation Fluorescence of Photosensitizers for Two-Photon Imaging and Photodynamic Therapy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 2700–2708.

- Srivatsan, A.; Jenkins, S.V.; Jeon, M.; Wu, Z.; Kim, C.; Chen, J.; Pandey, R. Gold Nanocage-Photosensitizer Conjugates for Dual-Modal Image-Guided Enhanced Photodynamic Therapy. Theranostics 2014, 4, 163–174.

- Kautzka, Z.; Clement, S.; Goldys, E.M.; Deng, W. Light-Triggered Liposomal Cargo Delivery Platform Incorporating Photosensitizers and Gold Nanoparticles for Enhanced Singlet Oxygen Generation and Increased Cytotoxicity. IJN 2017, 12, 969–977.

- Singh, S.P.; Alvi, S.B.; Pemmaraju, D.B.; Singh, A.D.; Manda, S.V.; Srivastava, R.; Rengan, A.K. NIR Triggered Liposome Gold Nanoparticles Entrapping Curcumin as in Situ Adjuvant for Photothermal Treatment of Skin Cancer. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 110, 375–382.

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Luo, L.; Li, L.; Zhu, R.Y.; Li, A.; He, Y.; Cao, W.; Niu, K.; Liu, H.; et al. Gold-Nanobranched-Shell Based Drug Vehicles with Ultrahigh Photothermal Efficiency for Chemo-Photothermal Therapy. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2019, 18, 303–314.

- Chauhan, D.S.; Prasad, R.; Devrukhkar, J.; Selvaraj, K.; Srivastava, R. Disintegrable NIR Light Triggered Gold Nanorods Supported Liposomal Nanohybrids for Cancer Theranostics. Bioconjugate Chem. 2018, 29, 1510–1518.

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Z.; Wang, L.; Luo, L.; Wang, M.; Wang, Q.; Gao, D. Gold Nanoshell-Based Betulinic Acid Liposomes for Synergistic Chemo-Photothermal Therapy. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2017, 13, 1891–1900.

- Hua, H.; Zhang, N.; Liu, D.; Song, L.; Liu, T.; Li, S.; Zhao, Y. Multifunctional Gold Nanorods and Docetaxel-Encapsulated Liposomes for Combined Thermo- and Chemotherapy. IJN 2017, 12, 7869–7884.

- Nguyen, V.D.; Min, H.-K.; Kim, C.-S.; Han, J.; Park, J.-O.; Choi, E. Folate Receptor-Targeted Liposomal Nanocomplex for Effective Synergistic Photothermal-Chemotherapy of Breast Cancer in Vivo. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2019, 173, 539–548.

- You, J.; Zhang, P.; Hu, F.; Du, Y.; Yuan, H.; Zhu, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, J.; Li, C. Near-Infrared Light-Sensitive Liposomes for the Enhanced Photothermal Tumor Treatment by the Combination with Chemotherapy. Pharm. Res. 2014, 31, 554–565.

- Li, Y.; Song, W.; Hu, Y.; Xia, Y.; Li, Z.; Lu, Y.; Shen, Y. “Petal-like” Size-Tunable Gold Wrapped Immunoliposome to Enhance Tumor Deep Penetration for Multimodal Guided Two-Step Strategy. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2021, 19, 293.

- Zhang, N.; Li, J.; Hou, R.; Zhang, J.; Wang, P.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Z. Bubble-Generating Nano-Lipid Carriers for Ultrasound/CT Imaging-Guided Efficient Tumor Therapy. Int. J. Pharm. 2017, 534, 251–262.

- Rengan, A.K.; Jagtap, M.; De, A.; Banerjee, R.; Srivastava, R. Multifunctional Gold Coated Thermo-Sensitive Liposomes for Multimodal Imaging and Photo-Thermal Therapy of Breast Cancer Cells. Nanoscale 2014, 6, 916–923.

- Park, J.-M.; Choi, H.E.; Kudaibergen, D.; Kim, J.-H.; Kim, K.S. Recent Advances in Hollow Gold Nanostructures for Biomedical Applications. Front. Chem. 2021, 9, 699284.

- You, J.; Zhang, G.; Li, C. Exceptionally High Payload of Doxorubicin in Hollow Gold Nanospheres for Near-Infrared Light-Triggered Drug Release. ACS Nano 2010, 4, 1033–1041.

- Xiong, C.; Lu, W.; Zhou, M.; Wen, X.; Li, C. Cisplatin-Loaded Hollow Gold Nanoparticles for Laser-Triggered Release. Cancer Nano 2018, 9, 6.

- Sonkar, R.; Sonali; Jha, A.; Viswanadh, M.K.; Burande, A.S.; Narendra; Pawde, D.M.; Patel, K.K.; Singh, M.; Koch, B.; et al. Gold Liposomes for Brain-Targeted Drug Delivery: Formulation and Brain Distribution Kinetics. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2021, 120, 111652.

- Kirui, D.K.; Celia, C.; Molinaro, R.; Bansal, S.S.; Cosco, D.; Fresta, M.; Shen, H.; Ferrari, M. Mild Hyperthermia Enhances Transport of Liposomal Gemcitabine and Improves In Vivo Therapeutic Response. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2015, 4, 1092–1103.

- Zhang, N.; Chen, H.; Liu, A.-Y.; Shen, J.-J.; Shah, V.; Zhang, C.; Hong, J.; Ding, Y. Gold Conjugate-Based Liposomes with Hybrid Cluster Bomb Structure for Liver Cancer Therapy. Biomaterials 2016, 74, 280–291.

- Hamzawy, M.A.; Abo-youssef, A.M.; Salem, H.F.; Mohammed, S.A. Antitumor Activity of Intratracheal Inhalation of Temozolomide (TMZ) Loaded into Gold Nanoparticles and/or Liposomes against Urethane-Induced Lung Cancer in BALB/c Mice. Drug Deliv. 2017, 24, 599–607.

- Deng, W.; Chen, W.; Clement, S.; Guller, A.; Zhao, Z.; Engel, A.; Goldys, E.M. Controlled Gene and Drug Release from a Liposomal Delivery Platform Triggered by X-Ray Radiation. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2713.

- Noh, J.; Kwon, B.; Han, E.; Park, M.; Yang, W.; Cho, W.; Yoo, W.; Khang, G.; Lee, D. Amplification of Oxidative Stress by a Dual Stimuli-Responsive Hybrid Drug Enhances Cancer Cell Death. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6907.

- Wei, X.; Liao, J.; Davoudi, Z.; Zheng, H.; Chen, J.; Li, D.; Xiong, X.; Yin, Y.; Yu, X.; Xiong, J.; et al. Folate Receptor-Targeted and GSH-Responsive Carboxymethyl Chitosan Nanoparticles Containing Covalently Entrapped 6-Mercaptopurine for Enhanced Intracellular Drug Delivery in Leukemia. Mar. Drugs 2018, 16, 439.

- Jeon, M.; Kim, G.; Lee, W.; Baek, S.; Jung, H.N.; Im, H.-J. Development of Theranostic Dual-Layered Au-Liposome for Effective Tumor Targeting and Photothermal Therapy. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2021, 19, 262.

- Kwon, H.J.; Byeon, Y.; Jeon, H.N.; Cho, S.H.; Han, H.D.; Shin, B.C. Gold Cluster-Labeled Thermosensitive Liposmes Enhance Triggered Drug Release in the Tumor Microenvironment by a Photothermal Effect. J. Control. Release 2015, 216, 132–139.

- Du, B.; Gu, X.; Han, X.; Ding, G.; Wang, Y.; Li, D.; Wang, E.; Wang, J. Lipid-Coated Gold Nanoparticles Functionalized by Folic Acid as Gene Vectors for Targeted Gene Delivery in Vitro and in Vivo. ChemMedChem 2017, 12, 1768–1775.

- Refaat, A.; del Rosal, B.; Palasubramaniam, J.; Pietersz, G.; Wang, X.; Moulton, S.E.; Peter, K. Near-Infrared Light-Responsive Liposomes for Protein Delivery: Towards Bleeding-Free Photothermally-Assisted Thrombolysis. J. Control. Release 2021, 337, 212–223.

- Grafals-Ruiz, N.; Rios-Vicil, C.I.; Lozada-Delgado, E.L.; Quiñones-Díaz, B.I.; Noriega-Rivera, R.A.; Martínez-Zayas, G.; Santana-Rivera, Y.; Santiago-Sánchez, G.S.; Valiyeva, F.; Vivas-Mejía, P.E. Brain Targeted Gold Liposomes Improve RNAi Delivery for Glioblastoma. IJN 2020, 15, 2809–2828.

- Jia, X.; Lv, M.; Fei, Y.; Dong, Q.; Wang, H.; Liu, Q.; Li, D.; Wang, J.; Wang, E. Facile One-Step Synthesis of NIR-Responsive SiRNA-Inorganic Hybrid Nanoplatform for Imaging-Guided Photothermal and Gene Synergistic Therapy. Biomaterials 2022, 282, 121404.

- Skalickova, S.; Nejdl, L.; Kudr, J.; Ruttkay-Nedecky, B.; Jimenez Jimenez, A.; Kopel, P.; Kremplova, M.; Masarik, M.; Stiborova, M.; Eckschlager, T.; et al. Fluorescence Characterization of Gold Modified Liposomes with Antisense N-Myc DNA Bound to the Magnetisable Particles with Encapsulated Anticancer Drugs (Doxorubicin, Ellipticine and Etoposide). Sensors 2016, 16, 290.

- An, S.S.; Kang, J.H.; Ko, Y.T. Lipid-Coated Gold Nanocomposites for Enhanced Cancer Therapy. IJN 2015, 10, 33–45.

- Kunjiappan, S.; Panneerselvam, T.; Somasundaram, B.; Arunachalam, S.; Sankaranarayanan, M.; Parasuraman, P. Preparation of Liposomes Encapsulated Epirubicin-Gold Nanoparticles for Tumor Specific Delivery and Release. Biomed. Phys. Eng. Express 2018, 4, 045027.

- Vigata, M.; Meinert, C.; Hutmacher, D.W.; Bock, N. Hydrogels as Drug Delivery Systems: A Review of Current Characterization and Evaluation Techniques. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 1188.

- Das, S.S.; Bharadwaj, P.; Bilal, M.; Barani, M.; Rahdar, A.; Taboada, P.; Bungau, S.; Kyzas, G.Z. Stimuli-Responsive Polymeric Nanocarriers for Drug Delivery, Imaging, and Theragnosis. Polymers 2020, 12, 1397.

- Thelu, H.V.P.; Albert, S.K.; Golla, M.; Krishnan, N.; Ram, D.; Srinivasula, S.M.; Varghese, R. Size Controllable DNA Nanogels from the Self-Assembly of DNA Nanostructures through Multivalent Host–Guest Interactions. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 222–230.

- Yao, C.; Yuan, Y.; Yang, D. Magnetic DNA Nanogels for Targeting Delivery and Multistimuli-Triggered Release of Anticancer Drugs. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2018, 1, 2012–2020.

- Zhang, C. Co-Delivery of 5-Fluorodeoxyuridine and Doxorubicin via Gold Nanoparticle Equipped with Affibody-DNA Hybrid Strands for Targeted Synergistic Chemotherapy of HER2 Overexpressing Breast Cancer. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 22015.

- Kumar, S.; Peng, X.; Daley, J.; Yang, L.; Shen, J.; Nguyen, N.; Bae, G.; Niu, H.; Peng, Y.; Hsieh, H.-J.; et al. Inhibition of DNA2 Nuclease as a Therapeutic Strategy Targeting Replication Stress in Cancer Cells. Oncogenesis 2017, 6, e319.

- Park, H.; Yang, J.; Lee, J.; Haam, S.; Choi, I.-H.; Yoo, K.-H. Multifunctional Nanoparticles for Combined Doxorubicin and Photothermal Treatments. ACS Nano 2009, 3, 2919–2926.

- Dai, M.; Ja, F. Engineered Protein Polymer-Gold Nanoparticle Hybrid Materials for Small Molecule Delivery. J. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. 2016, 7, 356.

More

Information

Subjects:

Nanoscience & Nanotechnology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

682

Revision:

1 time

(View History)

Update Date:

28 Oct 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No