1. Introduction

The surface area protected in the form of Biosphere Reserves continues to increase and has now reached the figure of 53 territories, which have been awarded this distinction by the UNESCO in the year 2021 in Spain.

This rise can be explained by the opportunities for conservation of the development of the sustainable use of these natural resources

[1]; as part of this use, the important role played by tourism should be emphasized.

Although it is true that tourist activities carried out in an uncontrolled manner can become a threat to the conservation of these spaces, the sustainable development of these activities is desirable both to develop the local communities and to generate income for the conservation of the protected space

[2]. In effect, as the authors of

[3] point out, socioeconomic development around protected spaces may help to avoid adverse effects such as checking depopulation and reducing the economic disparities suffered by rural areas.

For this reason, the sustainable management of natural spaces becomes an opportunity to create wealth and wellbeing in regions with little industrial development that see in the management of their natural legacy an opportunity to generate wealth and employment by the development of the service sector.

However, to achieve satisfactory tourist management of the natural space, it is essential to use suitable segmentation strategies. The segmentation of markets has habitually been used by marketing managers to get to know and understand differences between the potential tourists of a destination

[4]. Their importance to management lies in the fact that the suitable segmentation of a market allows destinations to anticipate development trends and offer highly diversified products to meet the needs of tourists

[5].

2. Protected Natural Spaces and Tourism: A Necessary Symbiosis

The protection of natural areas has a century-and-a-half-long history and is of a universal nature

[6]. It is worth highlighting the difference between the United States creating the first Nature Reserve in 1872 (that of Yellowstone) and after, insofar as the protection objectives of the territory established

[7]. For example, the Middle Ages saw the appearance of the first spaces protected for reasons related to hunting

[8] and with time spaces arose in which only the royalty and nobility could hunt

[7]. However, when President Grant created the first nature reserve in the USA, a new type of protected area was created, which is characterized by it being public and having recreation goals. From that year onwards, the number of protected spaces in the world has increased constantly

[7], which according to

[9] can be divided into three stages: (1) Between 1872 and 1975, the growth was helped by the beginning of the development of laws and regulations for the protection of the spaces, as well as by the creation of the first institutions that were specialized in the protection of the environment, both in a national and international sphere. There was also an event that contributed greatly to the declaration of new protected spaces, the first World Congress of Natural Reserves held in Seattle in 1962, since after it being held, around 80% of the protected areas of the world were created

[10]. (2) Between 1974 and 1992, both the policies for environmental conservation and the laws on the subject intensified and increased in number. In this second phase, the number of protected areas and their surface became more numerous all over the world, even if there existed some differences between countries. (3) The final stage began with the Rio de Janeiro summit in 1992, which marked the introduction of a new ideology regarding conservation, which links it with sustainability and its three pillars: society, environment, and ecology.

Regarding the current situation, in 2018, the protected territories attained 14.87% of the total surface area of the world

[11] and in some areas reached a much higher percentage, such as the EU with 18%. In the case of Spain, the most recent data available show that the country has protected 36.2% of the total of its land surface area and 12.3% of its marine surface area. It is also the European country that contributes the largest surface area to the Natura 2000 Network, 27.4% of the total surface area of the country, and that with the most Biosphere Reserves with 53

[12]. In the case of Extremadura, the target area of this research, the region has a total of 89 Special Conservation Areas (Zonas Especiales de Conservación, ZEC), which occupy a total of 933,772 hectares, and 71 Special Protection Areas (Zonas de Especial Protección de Aves, ZEPA) with a total surface area of 1,102,409 hectares. The protected areas are not only strategic enclaves for the protection of biodiversity and other heritage values; they also contribute towards people’s wellbeing

[12]. These data are the consequence of the important Spanish protectionist culture, which is based on the approval of the Law on Nature Reserves of the year 1916. Both the protected surface area and the various forms of protection have increased considerably, and the regulatory framework has been built up because of the regulations approved in the respective Autonomous Regions in accordance with the sharing of powers between them and the central government

[13].

An important factor which should be taken in account is the support of local communities for the establishing of the protected areas. In this sense, the economic and social circumstances influence the decisions of people as to whether to support the establishing of the protected areas

[14]; great efforts have been made to make society aware of the ecological and sociocultural values of the protected areas and to increase the involvement in the conservation process

[15]. The interaction of the tourists with the protected areas through observation or activities such as the practice of sports or education, when this is permitted, provides cultural and social benefits, in addition to increasing wellbeing and raising environmental awareness

[16].

However, the increase in tourism implies a series of negative impacts at both a national and international level

[17]. The literature fully describes the two-faced role of tourism in the sustenance of delicate environments, communities, and cultures

[18][19][20]. Concern for the environment and the negative effects mass tourism can have if uncontrolled have meant that sustainable tourism is attracting a great deal of attention

[21]; moreover, this new mode of tourism allows people to travel independently, safely and in comfort

[22].

Protected zones are a powerful way of managing land use, for sustainable development, and for nature conservation

[23], although seeking to comply with conservation objectives and the resulting arbitration of land use may cause conflict

[23]. For example, this occurs when the various parties have different visions of conservation objectives and one or several parties attempt to impose their interests at the cost of the interests of the remainder

[24][25]. In the next section, the researchers analyze the literature published on the demand for ecotourism in protected spaces.

3. The Demand for Ecotourism in Protected Spaces: A Revision of the Literature

Market segmentation is a relatively new concept

[26]. In 1956, Wendell Smith

[27] suggested that big and differentiated markets consist of many smaller and similar segments, and that targeting them allows the businesses (or in the researchers' case, the destinations) to (1) position themselves uniquely, offering a better product to their chosen target and (2) to create a long-term competitive advantage. Moreover, communicating with a smaller part of the market leads to reduced marketing expenses. The tourism industry has completely adopted and adapted the concept, and there is not a single organization without a strategy for marketing segmentation, and the focus can be, for example, on tourists of different origins or with different patterns of vacation benefits preferences

[26]. The pioneer of market segmentation was Josef Mazanec who, in 1984

[28], introduced the dominant approach in tourism marketing segmentation studies: cluster analysis. Even though cluster analysis dominates, there are also other techniques that have been adopted, like neural networks methods

[29].

A condition for a good market segmentation is to make the correct choice of breakdown variables

[30], which usually are socio-demographic, psychological or behavioral variables, as shown in

[31] for the case of the tourist accommodation market. However, Haley

[32] affirms that the most effective way to segment a market is the benefits customer (in the researchers' case, tourists) seek in each product, the advantage of this methodology being that it groups customers with similar real needs, which play a decisive role in the purchase of the product

[33][34][35]. Benefit segmentation has been applied in tourism mainly to segment tourists by their expected benefits of destinations, attractions, or activities

[36]; however, studies in the accommodation sector are scarcer

[37]. Usually, they are based on data extracted from interviews with customers and experts

[38], or factor analysis of surveys limited to subgroups of tourists, such as business travelers in luxury hotels

[39], female travelers

[40], AirBnB users

[37] or spa hotels

[41]. In the specific case of Spain, which is the country studied in this entry, Cordente-Rodríguez, Mondéjar-Jiménez and Villanueva-Álvaro

[42] analyzed excursionists in the Serranía de Cuenca National Park and divided them into two groups: those whose only motivation is to enjoy nature and natural resources and those who have multiple motivations; not only do they want to enjoy nature but also the gastronomy, as well as visiting villages to learn about their culture and traditions. The study by Carrascosa-López, Carvache-Franco, Mondéjar Jiménez and Carvache-Franco

[43], also carried out in the Serranía de Cuenca National Park and in the Albufera National Park, is similar to

[42] in that it presents the known segments of nature and multiple motivations, but it also presents a third new segment, reward and escape, which is related to the dimensions of nature, rewards and having fun.

Nature-based tourism is a broad term for which subgroups have appeared

[44][45], such as ecotourism, nature tourism and adventure tourism. The idea of ecotourism has been very popular in recent years and is a very frequent topic in literature. Ecotourism is close to sustainable tourism because they both should be ecologically, socially, and culturally sustainable, and minimize undesirable impacts on the environment

[46]. Ecotourism is the environmentally responsible travel to unmodified natural and cultural areas that promotes environmental learning while contributing to the conservation of the environment and to economic development

[47]. Nature tourism is the contemplation of fauna, flora, or landscape scenery

[47], so it shares only part of the ecotourism requirements: its link with nature, its attractiveness, and the experience of the visitors in natural settings

[46]. The purpose of adventure tourism is to involve participants in activities that imply a degree of perceived risk or controlled danger related to personal challenges

[48]. In addition to the subdivisions explained, authors such as

[49] suggested four segments using a motivation-based segmentation: ecotourism, wilderness use, adventure travel and camping,

[43] proposed combined, or hybrid, terms, to reflect the overlapping that tourist products present; for example, a tourist product can contain not only elements of adventure, but also natural and/or cultural attractions. Some studies have been published about benefit segmentation in the nature tourism industry. The author of

[50] identified four different segments of tourists in Belize (ecotourists, nature escapists, comfortable naturalists, and passive players), while Bricker and Kerstetter

[51] created four segments of tourists who decided to participate in a nature tour in the Fiji Islands (eco-family travelers, culture buffs, ecotourists and eclectic travelers). Kerstetter, Hou and Lin

[52] identified three segments of tourists in the coast of Taiwan, and labelled them experience-tourists, learning-tourists and ecotourists.

As for motivations, Holden and Sparrowhawk

[53] affirm that the main motivations for ecotourists are (1) learning about nature, (2) being physically active and (3) meeting people with the same interests, while Page and Dowling

[54] add that ecotourists travel to satisfy their recreational and leisure needs, as well as to gather information on specific zones. Pearce and Lee

[55] explain that motivating factors for travelling include relaxation, escaping, the improvement of relationships and personal development, among others. Kruger and Saayman

[56] observed that tourists travel to National Parks for six main reasons: searching for knowledge, experiencing nature, to take photographs, relaxing and escaping, experiencing the park’s characteristics and nostalgia, while, for South Korea, the seven main factors, following Lee et al.

[57], are linked with motivation, and are self-development, interpersonal links, reward, the construction of personal relationships, escape, ego-defensive function and the appreciation of nature. As for the Republic of Serbia, Panin and Mbrica

[58] divide ecotourists into four groups: social activities, health and sports activities, nature-related motivations, and educational activities.

The motivations of rural tourists, as well as their behaviors, are very different from those that do conventional tourism (López-Sanz et al., 2021)

[59]. Said motivations are, as studied by Lois et al.

[60], Tirado

[61], Devesa et al.

[62] and Leco et al.

[63], linked to nature, culture, and the environment. The cited authors proposed ten different main motivations for rural tourists, which are: contact with nature, rest and calmness, cleanliness of air and water, open-air spaces and healthy environment, gastronomy, activities related with agriculture, the discovery of new cultures, hospitality of the local population, contact with the heritage and travelling back in time while having the comfort of the present.

To complete the contextualization of this research, in the following section the researchers give a brief description of the Monfragüe Biosphere Reserve and its main characteristics.

4. The Monfragüe Biosphere Reserve: An Emblematic Protected Space in Southwestern Europe

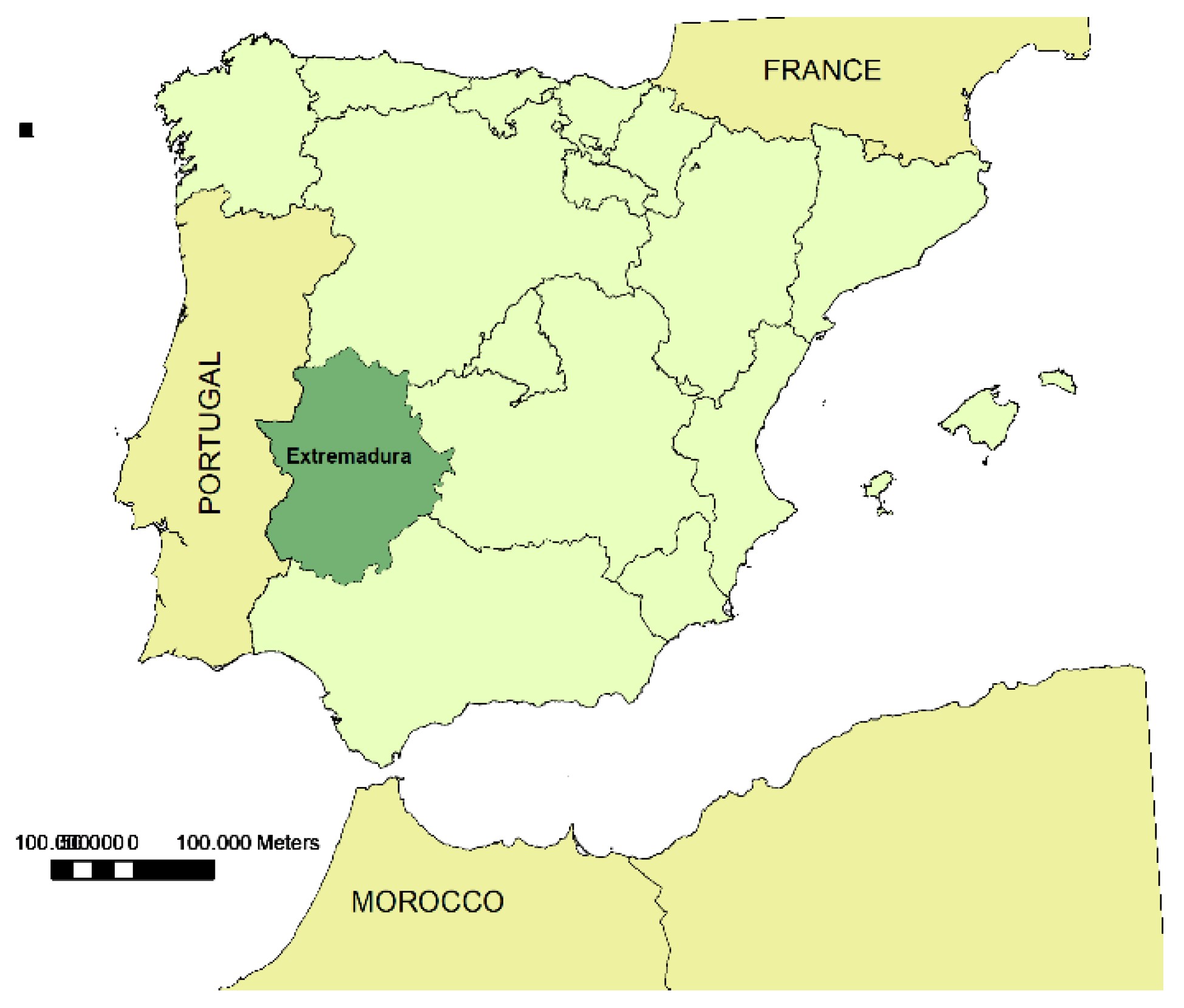

Extremadura is an Autonomous Region of Spain consisting of two provinces, Cáceres and Badajoz, which borders on Castilla y León to the north, Andalusia to the south, Castilla La Mancha to the east, and Portugal to the west (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Location of area of research. Source: own elaboration.

It has a total of 41,634 km

2, which corresponds to 8.2% of the surface area of Spain

[3]. The area subject of this research, the National Park of Monfragüe, can be found in the province of Cáceres; it is the largest area of Mediterranean woodland and the best preserved in the world, and it also has great biodiversity thanks to the rivers and reservoirs that irrigate it

[64]. According to data published by the Ministry for Ecological Transition and the Demographic Challenge (MITECO) in the Report of the Network of National Parks for 2019, Monfragüe National Park has a surface area of 18,396 hectares, a peripheral protected area of 97,764 hectares, and an area of socioeconomic influence of 195,500.73 hectares

[65]. Monfragüe has been a Special Protection Area since October 1998

[66]; this protection is recognized in the legislation of Extremadura by the Decree 232/2000 of 21 November. This recognition is highly relevant owing to the ornithological richness of Monfragüe as many tourists travel there to see the birds which nest in the park in their natural habitat, among which the black vulture stands out

[67]. In 2003, Monfragüe was recognized as a Biosphere Reserve

[67] and in 2007 the approval of Law 1/2007 of 2 March meant that Monfragüe was declared a National Park. Finally, Monfragüe was designated a Special Conservation Area in 2015

[68], which is reflected in the legislation of Extremadura by Decree 110/2015 of 19 May. The vegetation of the park makes it even more attractive with its holm oaks, cork oaks, and alders, among other species. As far as tourism is concerned, the latest data available of accommodation businesses and restaurants in Monfragüe, from December 2020, are shown in

Table 1.

As for the number of travelers, in 2020, a total of 38,235 visited Monfragüe and accounted for a total of 79,571 overnight stays; they remained in the park for an average of 2.08 days. These figures represent a decrease of 49% in the number of travelers and of 42.5% in the number of overnight stays compared with 2019

[69]. To conclude, although some aspects have already been mentioned, the researchers highlight below the main natural characteristics of Monfragüe National Park

[65]: (1) Monfragüe is the largest area of preserved Mediterranean woodland in the world and is crossed by the river Tagus. The great variety of natural environments explains the wide variety of both animal and plant species in the park. (2) The landscape is characterized by being the result of human action. The dehesa woodland and pastureland system is the most outstanding example of sustainable interaction between man and the environment. (3) The birds nesting in the park include the griffon vulture, the black stork, the peregrine falcon, and the eagle owl. (4) With regard to vegetation, Monfragüe has holm and cork oak groves, heaths, and populations of maples, ashes, and alders.