Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | J. Iñaki De La Peña Esteban | -- | 2139 | 2022-06-16 09:14:51 | | | |

| 2 | Vivi Li | + 33 word(s) | 2172 | 2022-06-17 04:42:27 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

De La Peña Esteban, J.I.; , .; Trigo Martínez, E. Insurance Solvency. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/24098 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

De La Peña Esteban JI, , Trigo Martínez E. Insurance Solvency. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/24098. Accessed February 07, 2026.

De La Peña Esteban, J. Iñaki, , Eduardo Trigo Martínez. "Insurance Solvency" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/24098 (accessed February 07, 2026).

De La Peña Esteban, J.I., , ., & Trigo Martínez, E. (2022, June 16). Insurance Solvency. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/24098

De La Peña Esteban, J. Iñaki, et al. "Insurance Solvency." Encyclopedia. Web. 16 June, 2022.

Copy Citation

Solvency must be understood as the guarantee of adequate capital to meet liabilities to policyholders and beneficiaries. Regulation can be adjusted to incorporate one or more elements of the above dimensions in order to make solvency more sustainable. There has been a change in the main regulations governing the solvency of the world’s main insurance markets. Sustainability is an issue that is becoming increasingly important among to the various stakeholders in the insurance industry. It is a complex concept that has many different dimensions that can be included in these regulations, allowing for a more sustainable solvency.

insurance sustainability

insurance supervision

risk management

capital requirements

solvency

1. Introduction

Sustainability is an increasingly important topic in the insurance industry. The debate began in 1997 with the creation of the United Nations Environment Programme Finance Initiative (UNEP FI) [1]. This organisation promotes research and development in sustainable insurance. Among others, the global survey on the status of sustainable insurance [2], the promulgation of the Principles for Sustainable Insurance [3] and the agenda for their implementation [4].

Sustainability is a concept that has various definitions [5] and dimensions [6] in the field of insurance industry’s investments (Table 1).

Table 1. Dimensions of sustainability in investments: Source: [6].

| Environmental | Social | Governance |

|---|---|---|

| Climate change | Human rights | Board structure, size, diversity, skills and independence |

| Renewable energy | Workplace health and safety | Executive pay |

| Air, water or resource depletion/pollution | Human capital management/employee relations | Bribery and corruption |

| Changes in land use | Diversity | Internal controls and risk management |

| Controversial weapons |

Solvency must be understood as the guarantee of adequate capital to meet liabilities to policyholders and beneficiaries. Regulation can be adjusted to incorporate one or more elements of the above dimensions in order to make solvency more sustainable (sustainable solvency [7]). In the insurance sector, the environmental dimension, especially climate change because of its impact on underwriting risk, and the governance dimension are important. The qualitative pillars of most insurance regulations deal with this dimension to a greater or lesser extent. However, the development of the concept of sustainable solvency in the literature is scarce and limited to several papers including [6][8][9][10][11].

The main purpose of insurers is to accept, manage and transfer Risks. Therefore, risk management is a fundamental element that must consider all these dimensions. According to [9], the dimensions in Table 1 require strategic risk management, while solvency, sustainable or not, requires tactical risk management.

In recent years, changes in solvency regulations have led to the development of tactical risk management and promoted a process of convergence, which analysis may be useful for strategic risk management. This is because some regulators [12][13][14] now consider that insurance regulation implicitly addresses the environmental and governance dimensions of sustainability and plan to address them explicitly in the future [14][15].

In the case of insurance companies, the relationship between sustainability and solvency has been through pensions [7]. Although there are areas such as Europe that have begun to establish processes such as the European commission for opinion on sustainability within Solvency II, focused on the suitability of the system, climate change mitigation and sustainable investments that are taken into account in solvency calculations [13].

Another link between these two concepts in the insurance industry is the solvency ratio related to socially responsible investments. Thus, companies that are more concerned about their sustainability also tend to have a strong focus on solvency [16]. The underlying idea is that there is a relationship between the needs of the policyholder, their future sustainability and solvency.

An evolutionary change has occurred because, since the 1990s, regulation of the global insurance industry has evolved from a simple rule-based legislation, which measures solvency in a static manner [10], to a more complex risk-based legislation, which measures solvency in a dynamic manner [11][17]. This process has been encouraged by the International Association of Insurance Supervisors (IAIS), [18][19], whose main objective is to protect the rights of policyholders and beneficiaries from insurance company insolvency. In this sense, the European Commission (EC) determines that adequate corporate governance is necessary because it leads to a more competitive and sustainable insurer in the long term [20][21].

Therefore, two regulatory models can be distinguished (Table 2) depending on how capital is incorporated into management. Some authors claim that principle-based models are more flexible [22]; however, most sophisticated models are imperfect because they depend on assumptions and inputs.

Numerous authors have investigated the predictive power of solvency models [23][24][25]; the establishment of minimum capital reduces insolvencies [26], although their complete elimination is impossible [27].

Regulation of the insurance sector may differ from country to country, depending on the structure and degree of regulators’ risk aversion, but its purpose is the same: to avoid bankruptcy.

Ref. [28] established a theoretical qualitative framework with seven criteria for model analysis and risk detection to analyse the capacity of a regulation/system to predict insolvencies. Which has been justified and critically discussed in the literature by different authors of the insurance market. This qualitative used by [29] to analyse the European Union model. Later, [30] extended this framework to eleven qualitative criteria in order to adapt them to the market changes (structures, risks and complexity), which was adapted to the latest regulatory changes by [31][32].

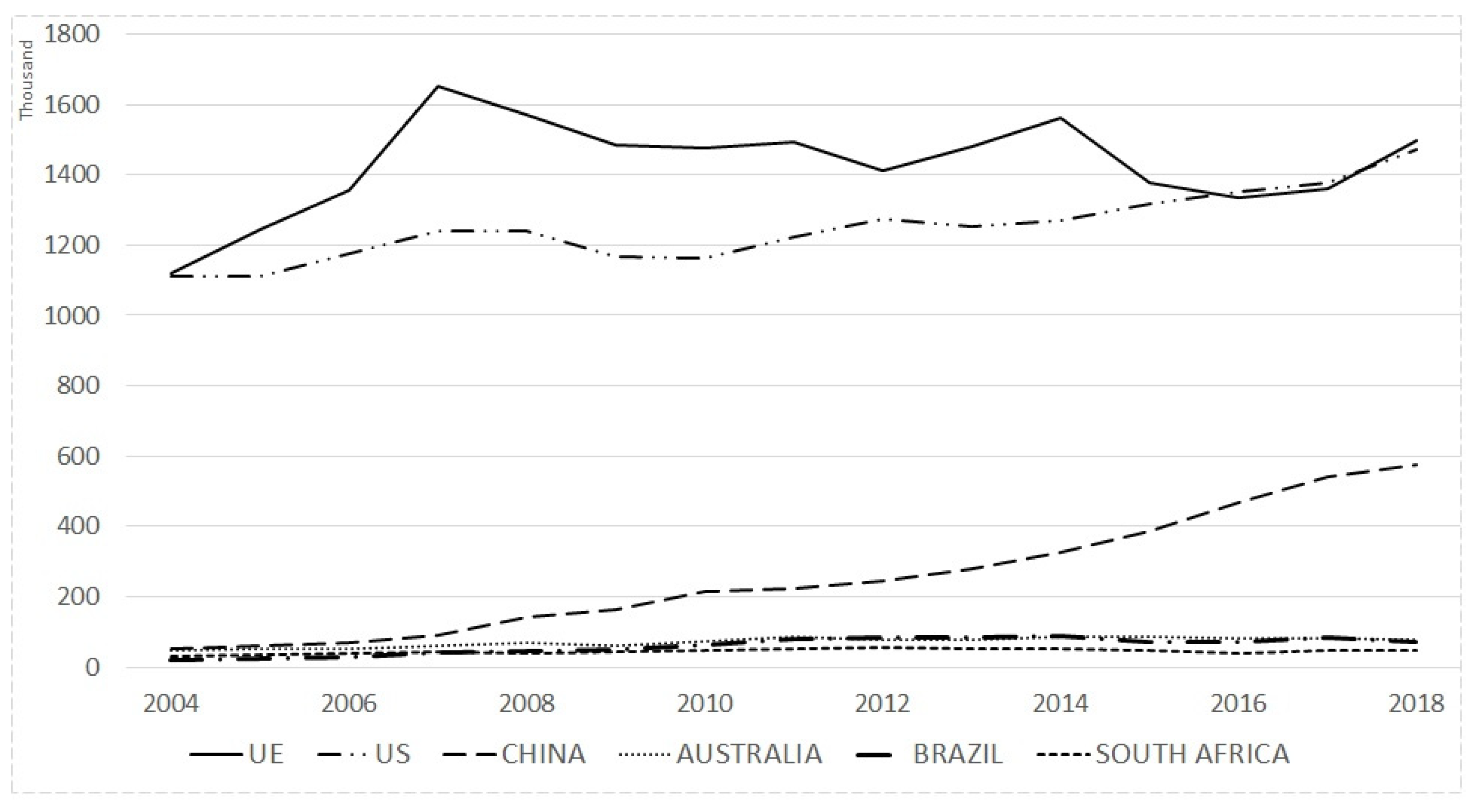

The aim of this entry is to find common principles for the development and convergence of the world’s most important solvency regulation models, which will increase innovation between different countries and therefore an increase in productivity. Researchers will also focus their analysis on the overall structure of the schemes without going into the life and non-life business, as most insurance systems use a comprehensive approach to risk. The selection criterion used is the volume of premiums marketed in 2018, according to the Swiss Report 2019, which is amongst the most relevant in the insurance market. The countries selected for each continent are the European Union (EU), United States (US), China, Australia, Brazil and South Africa (Figure 1). America is divided into North America and Latin America, and the European Union is considered a country because it represents 95.82% of Continental Europe and has common regulations [33].

Historically, the insurance market has focused on Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 3, because survival and mortality modelling are key within life and health business.

With the incursion of new solvency valuation systems, the focus has been shifting towards SDG 8, which focuses on business continuity as well as business development, so that policyholders are protected. Actuarial climate risk pricing models for floods, storms, winds and fires are currently being implemented. These models are aligned with SDG 13.

This SDG adaptation process is being developed following IAIS guidelines [18], conducted through the Own Risk and Solvency Assessment (ORSA).

The assessment requires the inclusion of qualitative factors linked to corporate governance and decision makers [29][31]. In addition, climate risk modelling is included, with the aim of addressing the challenges of the future. Most regulatory systems, however, address sustainability through company transparency and a long-term approach that contributes to company growth and corporate governance [47]. The insurance industry advocates management based on truthful and transparent reporting to stakeholders, oriented towards a reputational benefit [48].

In the insurance sector, solvency systems are not only quantitative but corporate governance leads the insurance industry to be sustainable.

2. Regulatory Changes in Insurance Solvency

2.1. European Union (Solvency II)

The European Union is one of the most important insurance markets in the world with a premium volume in 2018 of USD 1.49 trillion, representing 95.82% of the European market and 28.8% of the world market [46]

Prior to the Solvency II Directive (SII) [49], EU countries used a ratio-based methodology to determine solvency so that companies with different degrees of risk exposure could have the same solvency margin. SII provides for individualised risk management because the directive creates a global framework for risk management [50] and is structured on three pillars [51][52]: capital requirement, the monitoring process and corporative governance and market discipline. The paradigm change establishes new systems of corporate governance that will establish effective management, with good control of decision making as well as the qualification of decision makers. In fact, the second pillar of this directive focuses on this work, integrating governance into the day-to-day business of insurance companies [49]. Additionally, the importance of adapting to sustainability by incorporating demographic change or new environmental models. However, until it was initiated on 1 January 2016, its implementation was a long and slow process due to the complexity and number of countries involved [13].

SII has increased the need to develop and apply new methodologies for risk analysis [53] and requires the determination of solvency capital requirement (SCR) and minimum capital requirement (MCR), which can be calculated using two methods: standard formula or internal model. According to [54], there are several approaches that can be used for the standard formula (factor-based formula, scenario simulation, etc.), to guide companies towards better governance and thus more sustainability.

2.2. United States of America

Premium volume in 2018 in the US was USD 1.47 trillion, representing 92% of the North American market and 28.29% of the world market [46].

The US experienced major insolvencies in the 1980s and 1990s, which increased the interest of supervisors in regulation [55]. State regulators developed—through the National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC)—a uniform system composed of risk modules that established categories in which risk was measured by means of risk-based capital models [33]. This model was subsequently improved in many ways, including the development of life insurance scenarios. However, compared to other systems, it tends to separate the calculations according to whether the line of business is claims, life, etc.

In 2008, the Solvency Modernisation Initiative (SMI) began. This regulation has various objectives, including protecting policyholder interests and determining a solvency capital in line with the risk [38]; updating the regulatory framework for insurers, which dates back to the 1980s [39]; and limiting the frequency and severity of insurers’ insolvencies, which are very costly for policyholders and beneficiaries [56]. The SMI assesses solvency and also other areas of insurers such as capital requirements, governance and risk management, group supervision, statutory accounting and financial reporting and reinsurance [57]. These practices and processes support good management and are part of the increased importance of corporate governance to be developed in the light of the 2007–2013 crisis [58].

2.3. China

China’s premium volume has progressively increased and in 2018 was USD 574.877 billion, representing 11.06% of the world market and placing it behind the US.

The supervisory body is the China Insurance Regulatory Commission (CIRC) and its solvency model is the China Risk-Oriented Solvency System (C-ROSS), the project for which began in 2012 and was implemented in 2016. C-ROSS is consistent with a structure that requires asset and liability management [32] and focuses on three objectives: quantitative risk assessment, developing minimum capital and implementing a regulatory system.

The Chinese system follows the guidelines of the IAIS, [19] and the experience of SII. It is based on three pillars, according to its objectives: quantitative capital requirements, qualitative supervisory requirements and market discipline. Governance is addressed in the second and third pillars. Firstly, by establishing management requirements, as well as the evaluation of the company and its decision-makers. It then addresses the obligation of transparency of information and reporting to authorities.

2.4. Australia

Australia’s premium volume in 2018 was USD 79.98 million, ranking it thirteenth worldwide with 1.5% of the world market [46].

The supervisory and control body is the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA). The solvency model was introduced in 1973 by establishing the requirements for access to the insurance market [59], and in 2013 it was updated with the Life and General Insurance Capital Standards (LAGIC), whose aim is to standardize capital requirements and increase risk sensitivity.

The Australian model is similar to SII and is based on three pillars [60]. An insurer is compliant if its capital base exceeds 90% of the capital requirements [61][62][63] and also has appropriate valuation strategies and systems in place. However, it goes deeper into governance since its requirements are prescriptive, although the requirement for public information is more diffuse. Being part of the analysis not simply technical but of management and governance.

2.5. Brazil

Brazil is the leader in Latin America with 44.8% of the premium volume and ranks sixteenth worldwide with 1.4% of the world market [46].

The supervisory and control body is the Superintendence of Private Insurance (SUSEP). This body deals with the minimum capital requirement (MCR) for access to insurance activity, the definitions for the subsequent development of the solvency regulations and the capital requirements are in [64]. Current legislation identifies the MCR [55] and the main requirements for valuation [65][66].

2.6. South Africa

South Africa’s premium volume in 2018 was USD 48.269 million, ranking it nineteenth worldwide with 0.9% of the world market [46]. The supervisory and control body is the South African Reserve Bank. The regulation governing solvency is the Solvency Assessment and Management, which began in 2010 and was implemented in 2018.

This regulation complies with the Insurance Core Principles of the IAIS [19], is similar to SII and is based on three pillars: its objectives are to align the capital requirement with risk, to develop appropriate risk models for all insurers, to encourage the use of more sophisticated risk monitoring tools and to maintain financial stability [67]. Promotes governance, increases reporting and processes focused on the ORSA.

References

- Orie, M. The UN shift from social research to protecting the environment to governance-from Stockholm to Rio 1992 to Rio + 20 to the principles of sustainable insurance. Risk Man News 2012, 51, 12–16.

- UNEP, FI. The Global State of Sustainable Insurance Understanding and Integrating Environmental, Social and Governance Factors in Insurance. 2009. Available online: https://www.unepfi.org/fileadmin/documents/global-state-of-sustainable-insurance_01.pdf (accessed on 4 April 2022).

- UNEP, FI. Principles for Sustainable Insurance. 2012. Available online: https://www.unepfi.org/fileadmin/documents/PSI_document-en.pdf (accessed on 4 April 2022).

- UNEP, FI. Insurance 2030 Harnessing Insurance for Sustainable Development. 2009. Available online: https://www.unepfi.org/psi/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/Insurance_2030_FINAL6Oct2015.pdf (accessed on 4 April 2022).

- Nogueira, F.G.; Lucena, A.F.P.; Nogueira, R. Sustainable insurance assessment: Towards an integrative model. Geneva Pap. Risk Insur.—Issues Pract. 2017, 43, 275–299.

- Gatzert, N.; Reichel, P.; Zitzmann, A. Sustainability risks & opportunities in the insurance industry. German J. Risk Insur. 2020, 109, 311–331.

- Zhao, Y.; Bai, M.; Liu, Y.; Hao, J. Quantitative analyses of transition pension liabilities and solvency sustainability in China. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2252.

- Mills, E. From Risk to Opportunity: 2007: Insurer Responses to Climate Change, Ceres. 2007. Available online: https://insurance.lbl.gov/opportunities.html (accessed on 4 April 2022).

- Scordis, N.A.; Suzawa, Y.; Zwick, A.; Ruckner, L. Principles for Sustainable Insurance: Risk Management and Value. Risk Manag. Insur. Rev. 2014, 17, 265–276.

- Campagne, C.; van der Loo, A.; Yntema, J. Contribution to the method of calculating the stabilization reserve in life assurance business. In Gedenkboek Verzekeringskamer 1923–1948; Staatsdrukkerij- en uitgeverijbedrijf: Den Haag, The Netherlands, 1948; pp. 338–378.

- Campagne, C. Minimum Standards of Solvency for Insurance Firms; Report to the Report of the ad hoc Working Party on Minimum Standards of Solvency. OECD. TFD/PC/(61); OECD: Paris, France, 1961; Volume 1.

- PRA. The impact of climate change on the UK insurance sector. In A Climate Change Adaptation; Prudential Regulation Authority: London, UK, 2015.

- EIOPA. Opinion on Sustainability within Solvency II; EIOPA-BoS-19/241 30; European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority: Frankfurt am Main, Germany, September 2019.

- Grund, F. Sustainability: A duty and a challenge for the insurance industry. BaFin Perspect. 2019, 2, 29–33.

- EIOPA. Opinion on the Supervision of the Use of Climate Change Risk Scenarios in ORSA; EIOPA-BoS-21-127; European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority: Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 19 April 2021.

- Brogi, M.; Cappiello, A.; Lagasio, V.; Santoboni, F. Determinants of insurance companies’ environmental, social, and governance awareness. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022, 1–13.

- Eling, M.; Holzmüller, I. An overview and comparison of risk-based capital standards. J. Insur. Regul. 2008, 26, 31–60.

- IAIS. Principles on Capital Adequacy & Solvency; International Association of Insurance Supervisors: Basel, Switzerland, January 2002. Available online: http://amf.gov.al/pdf/publikime2/edukimi/sigurime/Principles%20on%20capital%20adequacy%20and%20solvency.pdf (accessed on 30 May 2021).

- IAIS. Insurance Core Principles; International Association of Insurance Supervisors: Basel, Switzerland, November 2018.

- EC. Recommendations on the Quality of the Information Presented in Relation to Corporate Governance; European Comission: Brussels, Belgium, 2014.

- Rajoria, D.K. Corporate governance and non-disclosure of material information: An insight into the Wadia case. Comp. Law J. 2020, 1, 33–40.

- Klein, R.W. Principles for insurance regulation: An evaluation of current practices and potential reforms. Geneva Pap. Risk Insur.—Issues Pract. 2011, 37, 175–199.

- Cummins, J.D.; Harrington, S.; Klein, R.W. Insolvency experience, risk-based capital, and prompt corrective action in property–liability insurance. J. Bank Financ. 1995, 19, 511–527.

- Cummins, J.D.; Grace, M.F.; Phillips, R.D. Regulatory Solvency prediction in property-liability insurance: Risk-based capital, audit ratios, and cash flow simulation. J. Risk Insur. 1999, 66, 417–458.

- Grace, M.; Harrington, S.; Klein, R.W. Risk-based capital and solvency screening in property-liability insurance. J. Risk Insur. 1998, 65, 213–243.

- Munch, T.; Smallwood, D.E. Theory of Solvency Regulation in the Property Casualty Insurance Industry; Cambridge ED: Boston, MA, USA, 1981.

- Park, S.C.; Tokutsune, Y. Do japanese policyholders care about insurers’ credit quality? Geneva Pap. Risk Insur.—Issues Pract. 2013, 38, 1–21.

- Cummins, J.D.; Harrington, S.; Niehaus, G. An economic overview of risk-based capital requirements for the property–liability insurance industry. J. Insur. Regul. 1994, 11, 427–447.

- Doff, R. A critical analysis of the solvency II proposals. Geneva Pap. Risk Insur.—Issues Pract. 2008, 33, 193–206.

- Holzmüller, I. The United States RBC standards, solvency II and the Swiss solvency test: A comparative assessment. Geneva Pap. Risk Insur.—Issues Pract. 2009, 34, 56–77.

- Garayeta, A.; De la Peña, J.I. Looking for a global standard of solvency for the insurance industry: Pros and cons in three systems. Transform. Bus. Econ. 2017, 16, 55–75.

- Fung, D.W.H.; Jou, D.; Shao, A.J.; Yeh, J.J.H. The china risk-oriented solvency system: A comparative assessment with other risk-based supervisory frameworks. Geneva Pap. Risk Insur.—Issues Pract. 2018, 43, 16–36.

- Swiss Re. World Insurance in 2019: Solid, But Mature Life Markets Weigh on Growth. Sigma, No.3. 2019. Available online: http://www.swissre.com/sigma/ (accessed on 30 May 2021).

- Swiss Re. World Insurance in 2006: Moderate Premium Growth, Attractive Profitability. Sigma, No.5. 2006. Available online: http://www.swissre.com/sigma/ (accessed on 28 February 2021).

- Swiss Re. World Insurance in 2007: Premiums Back to “Life”. Sigma, No.4. 2007. Available online: http://www.swissre.com/sigma/ (accessed on 28 February 2021).

- Swiss Re. Swiss Re. World Insurance in 2008: Emerging Markets Leading the Way. Sigma, No.3. 2008. Available online: http://www.swissre.com/sigma/ (accessed on 28 February 2021).

- Swiss Re. World Insurance in 2009: Life Premiums Fall in the Industrialised Countries—Strong Growth in the Emerging Economies. Sigma, No.3. 2009. Available online: http://www.swissre.com/sigma/ (accessed on 28 February 2021).

- Swiss Re. World Insurance in 2010: Premiums Dipped but Industry Capital Improved. Sigma, No.2. 2010. Available online: http://www.swissre.com/sigma/ (accessed on 28 February 2021).

- Swiss Re. World Insurance in 2011: Premiums Back to Growth—Capital Increase. Sigma, No.2. 2011. Available online: http://www.swissre.com/sigma/ (accessed on 28 February 2021).

- Swiss Re. World Insurance in 2012: Non-Life Ready for Take-Off. Sigma, No.3. 2012. Available online: http://www.swissre.com/sigma/ (accessed on 28 February 2021).

- Swiss Re. World Insurance in 2012: Progressing on the Long and Winding Road to Recovery. Sigma 2013, No.3. 2013. Available online: http://www.swissre.com/sigma/ (accessed on 30 May 2021).

- Swiss Re. World Insurance in 2013: Steering towards Recovery. Sigma, No 3. 2014. Available online: http://www.swissre.com/sigma/ (accessed on 30 May 2021).

- Swiss Re. World Insurance in 2015: Back to life. Sigma, No.4. 2015. Available online: http://www.swissre.com/sigma/ (accessed on 30 May 2021).

- Swiss Re. World Insurance in 2016: Steady Growth amid Regional Disparities. Sigma, No.3. 2016. Available online: http://www.swissre.com/sigma/ (accessed on 30 May 2021).

- Swiss Re. World Insurance in 2017: The China Growth Engine Steams Ahead. Sigma, No.3. 2017. Available online: http://www.swissre.com/sigma/ (accessed on 30 May 2021).

- Swiss Re. World Insurance in 2018: Solid, But Mature Life Markets Weigh on Growth. Sigma, No.3. 2018. Available online: http://www.swissre.com/sigma/ (accessed on 30 May 2021).

- Fung, B. The demand and need for transparency and disclosure in corporate governance. Univ. J. Manag. 2014, 2, 72–80.

- Orzes, G.; Moretto, A.M.; Moro, M.; Rossi, M.; Sartor, M.; Caniato, F.; Nassimbeni, G. The impact of the United Nations global compact on firm performance: A longitudinal analysis. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 227, 107664.

- EC. Directive 2009/138/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 November 2009 on the Taking-Up and Pursuit of the Business of Insurance and Reinsurance (Solvency II); European Commission: Brussel, Belgium, 2019.

- Eling, M.; Schmeiser, H.; Schmit, J.T. The solvency II process: Overview and critical analysis. Risk Manag. Insur. Rev. 2007, 10, 69–85.

- Stein, R.W. Are you ready for Solvency II? Bests Rev. 2006, 106, 88.

- Tarantino, A. Globalization efforts to improve internal controls. Account. Tod. 2005, 19, 37.

- Hernández Barros, R.; Martínez Torre-Enciso, M.I. Capital assessment of operational risk for the solvency of health insurance companies. J. Operat. Risk 2012, 7, 43–65.

- EC. The Draft Second wave calls for Advice from CEIOPS and Stakeholder Consultation on Solvency II; Markt/2515/04, Working Paper; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2004.

- Powers, M.R. A theory of risk, return and solvency. Insur Math Econ. 1995, 17, 101–118.

- AAA. Joint Report on SMI Project: 1–90; American Academy of Actuaries: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; Available online: http://www.actuary.org/content/joint-report-smi-project-0 (accessed on 30 May 2021).

- NAIC. Capital Requirements Governance & Risk Management; NAIC: 1–10. 2012; National Association of Insurance Commissioners: Kansas, MO, USA, 2012.

- Pottier, S.W.; Sommer, D.W. The effectiveness of public and private sector summary risk measures in predicting insurer insolvencies. J. Financial Serv. Res. 2002, 21, 101–116.

- AG. Insurance Act 1973 N° 76; 1976, Compilation N° 55; Australian Government: Canberra, Australian, 1973.

- PwC. Insurance Facts and Figures; Asian Region; PriceWaterhouseCoopers: Barangaroo, Australia, 2013.

- APRA. Life Insurance (Prudential Standard) Determination N°8 2012; Prudential Standard LPS 100 Solvency Standard; Australian Prudential Regulation Authority: Sydney, Australia. 2012. Available online: https://www.apra.gov.au/sites/default/files/120912_LAGIC_letter_life_insurance_temporary_solvency_standard_0.pdf (accessed on 18 May 2022).

- APRA. Life Insurance (Prudential Standard) Determination N°2 2012; Prudential Standard LPS 110 Capital Adequacy. Australian Prudential Regulation Authority: Sydney, Australia. 2012. Available online: https://jade.io/article/846159?at.hl=Life++Insurance+(prudential+standard)+determination+No+2+of+2012. (accessed on 18 May 2022).

- APRA. Life Insurance (Prudential Standard) Determination N°7 2012; Prudential Standard LPS 118 Capital Adequacy: Operational Risk Charge. Australian Prudential Regulation Authority: Sydney, Australia. 2012. Available online: https://jade.io/article/846154?at.hl=Life++Insurance+(prudential+standard)+determination+No+7+of+2012. (accessed on 18 May 2022).

- CNSP. Resolução CNSP n° 302. 2013; Provision on Minimum Capital Requirement for Authorisation and Operation and Solvency Regularisation Scheme for Insurance Companies, Open-End Supplementary Pension Fund Institutions, Capitalisation Societies and Local Reinsurers. Conselho Nacional De Seguros Privados: Brasilia, Brazil, 2013.

- CNSP. CNSP n° 321. 2015; Provides for Technical Provisions, Assets That Reduce the Need to Cover Technical Provisions, Risk Capital Based on Subscription, Credit, Operational and Market Risks, Adjusted Net Equity, Minimum Capital Required, Solvency Regularization Plan, Retention Limits, Criteria for Investments, Accounting Standards, Accounting Audit and Independent Actuarial Audit and Audit Committee for Insurance Companies, Open Complementary Pension Fund Entities, Capitalization Companies and Reinsurers. Conselho Nacional De Seguros Privados: Brasilia, Brazil, 2015.

- CNSP. Resolução CNSP n° 343 2016 26 de Dezembro; Conselho Nacional De Seguros Privados: Brasilia, Brazil, 26 December 2016.

- FSB. Solvency Assessment and Management (SAM) Roadmap; Financial Services Board: Pretoria, South Africa, November 2010.

More

Information

Subjects:

Others

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

784

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

17 Jun 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No