Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Deborah Schultz | + 2894 word(s) | 2894 | 2022-02-23 04:47:14 | | | |

| 2 | Dean Liu | -3 word(s) | 2891 | 2022-03-17 05:36:51 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Schultz, D. Crossing Borders in the Work of Perejaume. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/20622 (accessed on 14 March 2026).

Schultz D. Crossing Borders in the Work of Perejaume. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/20622. Accessed March 14, 2026.

Schultz, Deborah. "Crossing Borders in the Work of Perejaume" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/20622 (accessed March 14, 2026).

Schultz, D. (2022, March 16). Crossing Borders in the Work of Perejaume. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/20622

Schultz, Deborah. "Crossing Borders in the Work of Perejaume." Encyclopedia. Web. 16 March, 2022.

Copy Citation

The Catalan artist Perejaume (b. 1957) visualizes the migration of art movements across geographical and political borders. In doing so, the artist offers visual forms for intangible journeys through time and space. In sharp contrast to earlier concepts of the development of art, from Vasari’s cyclical model of rise and fall to Alfred H. Barr’s linear ‘Development of Cubism and Abstract Art’, Perejaume’s drawings offer a less definitive, more suggestive, visualization of the migration of art movements.

painting

drawing

art history

landscape

memory

conceptual art

poetry

1. The Landscape and Its Representation

Perejaume’s output challenges categorization, and any attempt at a precise definition proves inadequate. Gloria Moure has written of how ‘Perejaume does not pursue any single direction systematically, instead following spontaneous impulses that lead to the discovery of connections among language, time and space. His means are poetic rather than analytic […]’ (Moure 1988). As a Catalan it is perhaps unsurprising that Perejaume is concerned with borders. The political borders of Catalonia have changed over the course of its history with the region under French or Spanish authority while seeking its autonomy or independence. The Catalan language, banned under Franco from official use, confirms Catalonia’s cultural distinctiveness from its neighbors. Designated in 1979 as an ‘autonomous community’, a growing independence movement led to the 2017 referendum and declaration of independence. However, the process was declared illegal by the Constitutional Court of Spain, and the leading figures either fled the country or were imprisoned. Thus, borders and identity are particularly pertinent to Catalonia’s history. The relationship between the local, the neighboring and the universal can be considered integral to the cultural unconscious of the region and are fundamental to Perejaume’s work. The artist has asserted ‘The local and the universal are, I believe, the same thing’, arguing that these concepts should not be seen as oppositional but as mutually dependent (Gambrell 1990, p. 73). He notes that Joan Miró is often seen as a ‘Parisian or generically Spanish’ artist, rather than one from Montroig (where the artist often stayed at the family home) or Palma de Mallorca (the birthplace of Miró’s mother and wife and where he frequently holidayed). The argument is exaggerated and intentionally so in order to make the point that local specificity should be celebrated rather than overlooked and that not all modernist art was produced in metropolitan centers such as Paris. Art, Perejaume states, ‘should communicate difference as difference, perpetuating singularity, interpreting untranslatable essence into comprehended rarity’ (Gambrell 1990, p. 73).

Engagement with the land and the concept of the landscape as an artistic genre underpin Perejaume’s practice. He produces creative dialogues with nature as well as with the history of landscape art, especially pleinairism. An example of this dialogue is the wittily and imaginatively titled drawing The forests of Barbizon demand that Theodore Rousseau returns them the images (1995). The image is a blur, as if by drawing and painting nature Rousseau and his Barbizon School peers somehow extracted the visual form of the forest, and it can no longer be seen (Figure 1). The title personifies the forests, suggesting that they come to life and make unexpected demands. An exhibition catalogue essay by the artist makes a tangential connection with the words of Albrecht Dürer which are quoted to support his point: ‘For indeed, art hides itself in nature, and whoever can sketch it, has captured it’ (Perejaume 1990, p. 21).

Figure 1. Perejaume, The forests of Barbizon demand that Theodore Rousseau returns them the images (1995) mixed media on paper, 39 × 49 cm; courtesy Galeria Joan Prats and Perejaume.

Central to Perejaume’s practice is a playful but profound study of the relationship between art and nature. Whereas the Barbizon School artists found art in nature, nature had already begun to resemble art. The term picturesque is relevant here; although originally applied to a particular kind of landscape painting, during the eighteenth century it became common usage in describing a particular kind of landscape itself which, in turn, resembled that particular kind of landscape painting. Key features found in picturesque painting were sought out and highlighted such as withered trees, rough rocks and crags, streams, waterfalls and paths. The artifice of culture was mapped onto the natural world, which was then viewed through its prism. Perejaume contemplates this relationship, transposing the way in which nature and culture are conventionally thought of and refocusing the reader’s perception onto nature as a product of art:

Perhaps landscape is the result of so much gazing. Perhaps the gazes have taken shape and have made solid what others have seen, putting in order everything we have seen, growing, now without basis, and observing us as well. Perhaps painting is the world, aged and thinned-out through use, with things its signs, as if a powerful gaze had turned the pigments into what we now see.

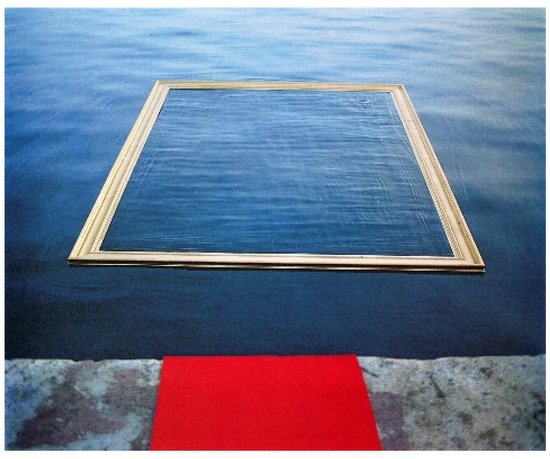

Perejaume seems to suggest that art has as much effect on nature, if not more, as nature has had on the history of art. In various works, he uses framing devices to highlight the ways in which we see nature through art. He has written that ‘we place a sheet of glass over the world with a frame around the edges’ (Searle 1993, p. 4). In works such as Marc al mar (Frame on the sea) (1986) the artifice of the frame is used to view nature (Figure 2). As a result, ‘everything is a painting’ (Searle 1993, p. 4). The frame becomes a fundamental part of the work as the viewer is made highly conscious of how we view the world through selective frames. In each work the frame can move, thereby changing the image.

Figure 2. Perejaume, Marc al mar (Frame on the sea) (1986) photograph, 30 × 40 cm; courtesy Galeria Joan Prats and Perejaume.

Perejaume makes the artifice of art explicit by taking art back to nature. As Adrian Searle has commented, ‘He has taken the frame and the label out of the museum and thrown them back into the world to show their incongruity, the uneasy conventions of the truce they appear to make between language and reality’ (Searle 1993, p. 4).

The frame defines the relationship between art and that which is within it, and nature or reality, which lie outside of it. In Marc al mar, however, the extensive sea lies both within and outside of the frame, suggesting that sometimes people cannot really distinguish between the two.

2. Displacement and Condensation

Throughout his practice, Perejaume uses images and words to prompt the viewer or reader to consider things differently, from another point of view. A black and white aerial photograph, Les lletres i el dibuix (Letters and Drawing) (2004), highlights networks of roads which, from the high perspective of the image, appear to be thin threads elegantly connecting and interweaving in space (Figure 3). Employing digital techniques, a number of sections of roads and motorways have been seamlessly combined to look like delicate drawings, making artificial structures appear natural and organic. Despite the digital methods used in its production, the work alludes to handwritten language with the sweeps and curves of the lines, retaining a sense of the handmade. For Perejaume, whether a natural river or valley, or a manmade path or road, power line or railway track, lines on the land or on a map can be seen as writing messages in their own language, these lines paralleling those of human communication. The image takes plein air drawing to a new height (both literally and metaphorically) leading to what Elena Vozmediano has described as ‘the verticalization of a horizontal reality’ (Vozmediano 2005, p. 124). Viewed vertically, the artist has created an abstract artifice resembling natural forms derived from manmade lines of communication.

Figure 3. Perejaume, Les lletres i el dibuix (Letters and Drawing) (2004) photograph, 231 × 127 cm; courtesy Galeria Joan Prats and Perejaume.

Perejaume extends his discussion of space to make connections between reading and walking. Both can be considered forms of movement through space and in both we seek to find our way. Although the route for the reader is shaped by the author, the reader’s response is not. A text may lead to all kinds of new paths of thought, and the reader may make connections that were not anticipated by the author. To apply a landscape analogy, the text may be dense, and the reader may need to go over the same ground a few times. By contrast, a walking route is less determined at the start. It may be shaped by the infrastructure of paths available; however, the walker can select their sequence in a way that the reader cannot. Perejaume focuses more on the similarities than the differences between reading and walking. He has written:

As both readers and walkers, we go from here to there, travelling through words, applying a jerky prose that turns and heads off down the path, and just when it is about to lose its way finds it again and continues. It is as if we looked out from the vantage point of words, from within words themselves, as if on a train, watching things pass by only half-read, bright and easily erasable.

The common feature here, for Perejaume, is words that take both readers and walkers on paths or routes that may be unexpected.

In other texts, the landscape acts as an analogy to the writing process itself. For example, when starting a new piece of writing, Perejaume argues that,

[…] we begin to create mountains with the bark kept from year to year, placing fresh plants and newly-gathered mosses there. There is a background with long and jointed phrases, among typographic plains and summits dusted with tiny writing and frosty blues.

At first, the reader has the impression that Perejaume is writing about nature, but then words are used unexpectedly, and a description of writing about a particular landscape turns into writing about writing. The illusion created by words is abruptly broken and the reader is reminded of how that illusion has been created. A piece of bark becomes a mountain, but the illusion and its materials are visible simultaneously.

Elsewhere, Perejaume applies other literary devices to visual works. Tautology is used to condense the space between nature and culture in Paint covering the ground (1995). This drawing, in turn, is reminiscent of Jorge Luis Borges’s map in his essay ‘On Exactitude in Science’, which entirely covers the territory it represents. Some of Perejaume’s drawings and paintings seem to map figuratively onto the land and become one with it. As the artist writes, ‘geography, civilized and artificial, made foundationless and mobile, is stretched out tightly across reality, covering it completely’ (Perejaume 1991, p. 46). People see the land through maps and other manmade or artificial geographical means. Paint covering the ground depicts a relief map covered with paint, thus succinctly fusing the landscape with the material of its representation in science (the map) and art (painting). Teló de muntanyes (2) (Mountain curtain 2) (2007) represents a mountainous landscape in which the distance is depicted in naturalistic details while the foreground breaks down into marks of paint, that is, the means of its representation. The image is viewed as if from behind a curtain, a small detail of which appears on its right-hand side. Perejaume engages the artifice of theatre to display both nature and its representation in art in which the two are fused together.

Mountains feature prominently in Perejaume’s work. They represent not only a key aspect of landscape art but also a challenge of nature which, he suggests, the modern and the contemporary world have physically and metaphorically overlooked. In contrast to the linearity of air travel, Perejaume’s undulating curves hug the landscape. As he has written, ‘The straight line of the modern movement has devalued orography with a levelling tourism of distances and backroads, and set the artist-subject, the work, or the tendency, far above the place’ (Perejaume 1989, p. 134). Instead, Perejaume’s feet are firmly on the ground, in the landscape, his paintbrush covering every inch of it directly. Here, painting and nature become as one.

A poem provides a good example of the artist’s method of dissolving verbal spaces too. Just as the space between nature and its representation is omitted, so too some elements that might be considered fundamental to any composition are left out thereby causing us to reconsider what we are presented with. In Grind, for example, he describes colors used to produce pigments, before turning to the possibilities of what these pigments might represent:

GRIND

- Azurite blue, malachite green

- reds and yellows of cinnabar

- vermilion, realgar, and orpiment

- minium orange, gypsum white.

- In a small mortar grind up the entire world.

Notably, the words ‘paint’ and ‘painting’ are not used. By omitting them, the poem highlights the absurdity of colored pigments representing the world. However, if people look beyond illusion to how that illusion has been created, has painting not done just this for centuries? Here, Perejaume draws on methods of displacement and condensation. Employed by surrealists, most notably in the visual arts by René Magritte, these methods make unexpected changes to the familiar, leading the viewer or reader to encounter them with greater consciousness. The words of the poem move from the micro of pigment to the macro of ‘the entire world’, missing out and thereby highlighting the spaces we inhabit.

3. Paisajismo and ‘The Impossibility of Translating Nature into Art’

In contrast to his use of condensation and displacement, Perejaume has defined the concept of paisajismo or ‘landscapism’ as ‘a response to the impossibility of translating nature into art. People try to take the outside inside in order to be able to understand what’s out there’ (Gambrell 1990, p. 68). Here, Perejaume argues that there is an ‘impossible distance between the subject and the landscape’ (Gambrell 1990, p. 70). Very occasionally art can defeat this distance: ‘Only a miraculous art is at times able to satisfy us—subjectives and subjects of the real—here among these two eminently sufficient geographies, among these two disunited but dependent territories: the world, so far away from us; and our world, wherever it might be’ (Perejaume 1991, p. 47). In his distinct writing style and use of language, Perejaume covers a point multiple times, coming at it from different directions and making all kinds of connections along the way. As Rebecca Solnit has commented succinctly with reference to Borges’s tautological map, ‘No representation is complete’ (Solnit 2017, p. 162). Thus, the land or landscape, the subject and art are explored in a myriad of ways. Perejaume emphasizes the materiality of art and of writing, using his words carefully and unexpectedly to keep the reader aware that s/he is reading ideas, and these ideas take shape but are unstable, continually moving and mutating.

For Perejaume, art, in particular paisajismo, has a vital interrelational role to play in the relationship between culture and nature. Aside from those rare occasions when we encounter ‘miraculous art’, art acts as an intermediary. He writes, art is ‘the only connection between the subject (the “I”) and nature. The painting is the nexus, the diphthong, the meeting place between the subject and nature […] The picture is a kind of nostalgic souvenir of this encounter’ (Gambrell 1990, p. 68). Although the distance between the subject and nature persists, a wide-ranging combination of diverse approaches offers a series of creative encounters.

In producing a blur rather than an illusion of nature, Perejaume asks us to reconsider the relationship between art and the natural world in The forests of Barbizon demand that Theodore Rousseau returns them the images. In contrast to the mimetic role of some landscape art, this drawing emphasizes the space or difference, the ‘impossible distance’ between man, the landscape and its artificial representation. As he wrote in ‘Two Geographies’, ‘the faithful reproduction, never completely attained, has opted for the invention of its own geography, another world made up of the substance that we speak with and look with’ (Perejaume 1991, p. 46). Here, he emphasizes the distinction between landscape and the materiality of painting or other forms of language. ‘These days’, Perejaume argues, ‘we affirm the existence of two geographies similar in both size and level of realism’ (Perejaume 1991, p. 46). Photography developed at the same time as Barbizon School painting, and he notes its central role of seeming to close the space between reality and its representation. By contrast, his own works are produced in ‘words and pigments’ and other forms that do not conceal their artifice. His paint handling, for example, is loose and textured with the paint firmly visible. The frames he uses are bold and heavy. His words take unexpected turns. Thus, Perejaume explores the relationship between art and nature in which art is differentiated from nature, ‘yet, at the same time they correspond and proliferate, independent and complete, marking out separate and distinct spheres in a divergent cartography’ (Perejaume 1991, p. 46). His words echo those above regarding the relationship between the local and the universal: in each case, difference is part of a productive dialogue between the two. By emphasizing the artifice of art, he explores its effect on how we view, consider and interact with nature. Thus, for Perejaume, art plays a vital role: ‘Capable of opening up gaps and breaches, fundamentally intermediary, art is the lapse, a no-man’s land, situated between nature and signature on the level of both geographies, constituted on top of the possibility of a real connection by its own relational ties’ (Perejaume 1991, p. 46).

References

- Moure, Gloria. 1988. Perejaume. Artforum, January. 126.

- Gambrell, Jamey. 1990. Interview with Perejaume. In Imágenes Líricas/New Spanish Visions. Exhibition catalogue. Edited by Lucinda Barnes. Long Beach: University Art Museum, pp. 66–75.

- Perejaume. 1990. Montblanc, Mont-Roig, Montnegre. In Perejaume. Barcelona: Galeria Joan Prats, pp. 21–37.

- Perejaume. 1991. Geographers and Poets, Two Geographies, Pessebrism, Nature and Signature and Authors and Toponomy. In Perejaume: El Grado de verdad de las Representaciones. Translated by Jeffrey Swartz. Madrid: Galeria Soledad Lorenzo, pp. 43–53.

- Searle, Adrian. 1993. Everything is a Painting. In Perejaume. Landscapes and Long Distances. Bristol: Arnolfini, pp. 4–9.

- Vozmediano, Elena. 2005. Perejaume. In Afinidades Electivas. Madrid: ARCO, pp. 124–27.

- Perejaume. 1989. Contribution to ‘The Global Issue’. Art in America, July. 134.

- Perejaume. 1999. Selection of Writings. Edited by Perejaume with the assistance of Pere Gimferrer and Carles Guerra. In Perejaume. Dis-Exhibit. Barcelona: MACBA.

- Solnit, Rebecca. 2017. A Field Guide to Getting Lost. Edinburgh: Canongate.

More

Information

Subjects:

Art

Contributor

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

729

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

17 Mar 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No