| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Fábio Rodrigo Piovezani Rocha | + 3543 word(s) | 3543 | 2022-03-01 07:04:40 | | | |

| 2 | Lindsay Dong | Meta information modification | 3543 | 2022-03-08 03:28:53 | | | | |

| 3 | Elias Ayres Guidetti Zagatto | Meta information modification | 3543 | 2022-03-08 13:08:28 | | |

Video Upload Options

Chemical derivatization involves modification of the analyte for improving selectivity and/or sensitivity. It is particularly attractive in flow analysis in view of its highly reproducible reagent addition(s) and controlled timing. Then, measurements without attaining the steady state, kinetic discrimination, exploitation of unstable reagents and/or products, as well as strategies compliant with Green Analytical Chemistry, have been efficiently exploited. Flow-based chemical derivatization has been accomplished by different approaches, involving e.g. flow and manifold programming, solid-phase reagents, and strategies for sample insertion and reagent addition, as well as to increase sample residence time.

1. Introduction

2. Chemical Derivatization

2.1. Types of Flow-Based Chemical Derivatizations

2.1.1. Catalytic Methods

2.1.2. Photochemical and Electrochemical Derivatization

2.1.3. Discolorimetry

2.1.4. Analyte Volatilization

2.1.5. Other Approaches

2.2. Derivatization in Liquid Chromatography

3. Flow-based Approaches for Chemical Derivatization

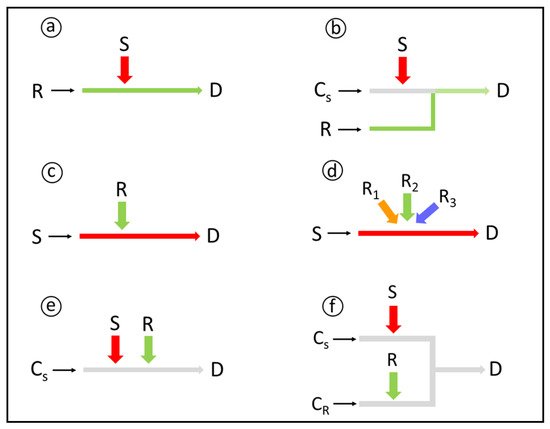

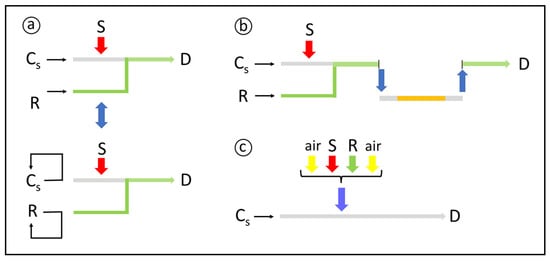

3.1. Strategies for Reagents and Sample Additions

Solid-phase reagents can be exploited for chemical derivatization in flow analysis, either as packed mini-columns [33], open tubular reactors [34], or suspensions [35]. Advantages include a low reagent consumption, increase of the reaction rate due to the reagent excess, possibility of using slightly soluble reagents, avoidance of dilution effects, and manifold simplification. On the other hand, strategies for minimizing reagent lixiviation (e.g. reagent chemically bound to the solid support) and backpressure effects (e.g. suitable particle size and/or porous materials) should be applied.

3.2. Mixing Conditions

3.3. Reproducible Timing

4. Highlights of Chemical Derivatization in Flow Analysis

4.1. Kinetic Methods

4.2. Unstable Reagents and Products

4.3. Optosensing

4.4. Simultaneous Determinations and Chemical Speciation

4.5. Green Analytical Methods

4.6. Expert Systems

5. Final Remarks

Chemical derivatization benefits itself from the favorable characteristics of flow analysis, allowing a better exploitation of chemical reactions without attaining equilibrium, the possibility of kinetic discrimination, the exploitation of unstable reagents and products, and the compliance with the GAC principles.

Most flow-based applications involve a simple mechanization of well-established analytical methods. Nevertheless, the advantages are increased when chemical derivatization exploits the characteristics inherent to flow analysis. This is a fertile field for further development, also when the flow analyzer is a front-of-end for chromatography.

The term “derivatization” is typically associated to chromatography, mass spectrometry, UV-vis spectrophotometry, and luminescence. However, its relevance to flow analysis has been increasingly emphasized. This also holds for µFIA and microfluidic devices.

In spite of the outstanding current development of flow analysis, an intense human labor is still required to minimize systematic errors and to ensure reliable analytical results and safer working conditions to the analysts. In this context, the development of expert systems plays an important role.

Several environmentally friendly innovations have been proposed for chemical derivatizations in flow analysis and the flow-based systems paved the way for making chemical derivatization a useful strategy for GAC. This is a counterpoint to the less realistic statement of GAC principle that chemical derivatization should be avoided [67].

References

- Irina Timofeeva; Lawrence Nugbienyo; Aleksei Pochivalov; Christina Vakh; Andrey Shishov; Andrey Bulatov; Flow-based methods and their applications in chemical analysis. ChemTexts 2021, 7, 1-24, 10.1007/s40828-021-00149-8.

- Elias A.G. Zagatto; Fábio R.P. Rocha; Large-scale flow analysis: From repetitive assays to expert analyzers. Talanta 2021, 233, 122479, 10.1016/j.talanta.2021.122479.

- Wanessa R. Melchert; Boaventura F. Reis; Fábio R.P. Rocha; Green chemistry and the evolution of flow analysis. A review. Analytica Chimica Acta 2012, 714, 8-19, 10.1016/j.aca.2011.11.044.

- Jaromir Ruzicka; From continuous flow analysis to programmable Flow Injection techniques. A history and tutorial of emerging methodologies. Talanta 2016, 158, 299-305, 10.1016/j.talanta.2016.05.070.

- Fábio R.P. Rocha; Boaventura F. Reis; Elias A.G. Zagatto; José L.F.C. Lima; Rui A.S. Lapa; João L.M. Santos; Multicommutation in flow analysis: concepts, applications and trends. Analytica Chimica Acta 2002, 468, 119-131, 10.1016/s0003-2670(02)00628-1.

- Eulogio J. Llorent-Martínez; Pilar Ortega-Barrales; M. Fernandez-De Cordova; Antonio Ruiz-Medina; Multicommutation in flow systems: A useful tool for pharmaceutical and clinical analysis. Current Pharmaceutical Analysis 2010, 6, 53-65, 10.2174/157341210790780195.

- Ove. Aastroem; Flow injection analysis for the determination of bismuth by atomic absorption spectrometry with hydride generation. Analytical Chemistry 1982, 54, 190-193, 10.1021/ac00239a011.

- Piyawan Phansi; Kaewta Danchana; Víctor Cerdà; Kinetic thermometric methods in analytical chemistry. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2017, 97, 316-325, 10.1016/j.trac.2017.09.019.

- György Marko-Varga; Lo Gorton; Post-column derivatization in liquid chromatography using immobilized enzyme reactors and amperometric detection. Analytica Chimica Acta 1990, 234, 13-29, 10.1016/s0003-2670(00)83534-5.

- Inês P.A. Morais; Ildikó V. Tóth; António O.S.S. Rangel; Turbidimetric and nephelometric flow analysis: concepts and applications. Spectroscopy Letters 2006, 39, 547-579, 10.1080/00387010600824629.

- Raquel P. Sartini; Cláudio C. Oliveira; Elias A.G. Zagatto; Henrique Bergamin Filho; Determination of reducing sugars by flow injection gravimetry. Analytica Chimica Acta 1998, 366, 119-125, 10.1016/s0003-2670(97)00725-3.

- Philip Fletcher; Kevin N. Andrew; Antony Calokerinos; Stuart Forbes; Paul J. Worsfold; Analytical applications of flow injection with chemiluminescence detection. A review. Luminescence 2000, 16, 1-23, 10.1002/bio.607.

- Derivatization. In Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary; Merriam-Webster Inc.: Massachusetts, USA, 1999 ISBN 9780786247745

- I.D. Wilson; E.R. Adlard; M. Cooke; C.F. Poole Derivatization. In Encyclopedia of Separation Science; Academic Press Inc.: San Diego, California, USA, 2000 ISBN 978-0-12-226770-3.

- Josef Drozd; Chemical derivatization in gas chromatography. Journal of Chromatography A 1975, 113, 303-356, 10.1016/s0021-9673(00)95303-2.

- W. Rudolf Seitz; R.W. Frei; Fluorescence derivatization. C R C Critical Reviews in Analytical Chemistry 1979, 8, 367-405, 10.1080/10408348008542715.

- H. Müller; Catalytic methods of analysis: Characterization, classification and methodology (Technical Report). Pure and Applied Chemistry 1994, 67, 601-613, 10.1351/pac199567040601.

- Takeshi Yamane; Tsutomu Fukasawa; Flow injection determination of trace vanadium with catalytic photometric detection. Analytica Chimica Acta 1980, 119, 389-392, 10.1016/s0003-2670(01)93642-6.

- Diogo L. Rocha; Marcos Y. Kamogawa; Fábio R.P. Rocha; A critical review on photochemical conversions in flow analysis. Analytica Chimica Acta 2015, 896, 11-33, 10.1016/j.aca.2015.09.027.

- Susan M. Lunte; Pre- and post-column derivatization reactions for liquid chromatography—electrochemistry. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry 1991, 10, 97-102, 10.1016/0165-9936(91)85079-7.

- M.A.J. van Opstal; J.S. Blauw; J.J.M. Holthuis; W.P. van Bennekom; A. Bult; On-line electrochemical derivatization combined with diode-array detection in flow-injection analysis : Rapid Determination of Etoposide and Teniposide in Blood Plasma. Analytica Chimica Acta 1987, 202, 35-47, 10.1016/s0003-2670(00)85900-0.

- Severino C.B. Oliveira; Elaine C.S. Coelho; Thiago M.G. Selva; Francyana P. Santos; Mário C.U. Araújo; Fabiane C. Abreu; Valberes B. Nascimento; A coulometric flow cell for in-line generation of reagent, titrant or standard solutions. Microchemical Journal 2006, 82, 220-225, 10.1016/j.microc.2006.01.009.

- Rejane M. Frizzarin; Fábio R.P. Rocha; A multi-pumping flow-based procedure with improved sensitivity for the spectrophotometric determination of acid-dissociable cyanide in natural waters. Analytica Chimica Acta 2012, 758, 108-113, 10.1016/j.aca.2012.10.059.

- W.E. van Der Linden; Membrane separation in flow injection analysis: Gas Diffusion. Analytica Chimica Acta 1983, 151, 359-369, 10.1016/s0003-2670(00)80097-5.

- Elias A.G. Zagatto; Cláudio C. Oliveira; Alan Townshend; Paul J. Worsfold. Flow analysis with spectrophotometric and luminometric detection; Elsevier: Amsterdam, 2012; pp. 471.

- M. van Son; R.C. Schothorst; G. den Boef; Determination of total ammoniacal introgen in water by flow injection analysis and a gas diffusion membrane. Analytica Chimica Acta 1983, 153, 271-275, 10.1016/s0003-2670(00)85513-0.

- Hualing Duan; Zhenbin Gong; Shifeng Yang; Online photochemical vapour generation of inorganic tin for inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometric detection. Journal of Analytical Atomic Spectrometry 2014, 30, 410-416, 10.1039/C4JA00249K.

- Michal Alexovič; Burkhard Horstkotte; Ivana Horstkotte Šrámková; Petr Solich; Ján Sabo; Automation of dispersive liquid–liquid microextraction and related techniques. Approaches based on flow, batch, flow-batch and in-syringe modes. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2016, 86, 39-55, 10.1016/j.trac.2016.10.003.

- Carlos Calderilla; Fernando Maya; Luz O. Leal; Víctor Cerdà; Recent advances in flow-based automated solid-phase extraction. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2018, 108, 370-380, 10.1016/j.trac.2018.09.011.

- Ana Cristi B. Dias; Eduardo P. Borges; Elias A.G. Zagatto; Paul J. Worsfold; A critical examination of the components of the Schlieren effect in flow analysis. Talanta 2006, 68, 1076-1082, 10.1016/j.talanta.2005.06.071.

- Fotouh R. Mansour; Neil D. Danielson; Reverse flow-injection analysis. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2012, 40, 1-14, 10.1016/j.trac.2012.06.006.

- Patrícia B. Martelli; Fábio R.P. Rocha; Rejane C.P. Gorga; Boaventura F. Reis; A flow system for spectrophotometric multidetermination in water exploiting reagent injection. Journal of the Brazilian Chemical Society 2002, 13, 642-646, 10.1590/s0103-50532002000500016.

- M.D. Luque de Castro; Solid-phase reactors in flow injection analysis. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry 1992, 11, 149-155, 10.1016/0165-9936(92)87077-w.

- Shuhei Yonezawa; Fujio Morishita; Tsugio Kojima; Simultaneous determination of triglycerides and .BETA.-D-glucose by flow injection analysis using enzyme immobilized open tubular reactors.. Analytical Sciences 1986, 3, 553-556, 10.2116/analsci.3.553.

- Andrey Shishov; Andrey Zabrodin; Leonid Moskvin; Vasil Andruch; Andrey Bulatov; Interfacial reaction using particle-immobilized reagents in a fluidized reactor. Determination of glycerol in biodiesel. Analytica Chimica Acta 2016, 914, 75-80, 10.1016/j.aca.2016.02.004.

- Pablo González; Moisés Knochen; Milton K. Sasaki; Elias A.G. Zagatto; Pulsed flows in flow analysis: Potentialities, limitations and applications. Talanta 2015, 143, 419-430, 10.1016/j.talanta.2015.05.018.

- Tuanne R. Dias; Wanessa R. Melchert; Marcos Y. Kamogawa; Fábio R.P. Rocha; Elias A.G. Zagatto; Fluidized particles in flow analysis: potentialities, limitations and applications. Talanta 2018, 184, 325-331, 10.1016/j.talanta.2018.02.072.

- Thomas Guebeli; Gary D. Christian; Jaromir Ruzicka; Fundamentals of sinusoidal flow sequential injection spectrophotometry. Analytical Chemistry 1991, 63, 2407-2413, 10.1021/ac00021a005.

- Jaromir Ruzicka; Graham D. Marshall; Sequential injection: a new concept for chemical sensors, process analysis and laboratory assays. Analytica Chimica Acta 1990, 237, 329-343, 10.1016/s0003-2670(00)83937-9.

- Paulo H.G.D. Diniz; Luciano F. Almeida; David P. Harding; Mário C.U. Araújo; Flow-batch analysis. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2012, 35, 39-49, 10.1016/j.trac.2012.02.009.

- Burkhard Horstkotte; Petr Solich; The automation technique lab-in-syringe: a practical guide. Molecules 2020, 25, 1612, 10.3390/molecules25071612.

- Celio Pasquini; Walace A. De Oliveira; Monosegmented system for continuous flow analysis. Spectrophotometric determination of chromium(VI), ammonia and phosphorus. Analytical Chemistry 1985, 57, 2575-2579, 10.1021/ac00290a033.

- Kaj Petersen; Purnendu K. Dasgupta; An air-carrier continuous analysis system. Talanta 1989, 36, 49-61, 10.1016/0039-9140(89)80081-5.

- Gary D. Christian; Jaromir Růz̆ic̆ka; Exploiting stopped-flow injection methods for quantitative chemical assays. Analytica Chimica Acta 1992, 261, 11-21, 10.1016/0003-2670(92)80170-c.

- Cristiane A. Tumang; Gilmara C. Luca; Ridvan N. Fernandes; Boaventura F. Reis; Francisco J. Krug; Multicommutation in flow analysis exploiting a multizone trapping approach: spectrophotometric determination of boron in plants. Analytica Chimica Acta 1998, 374, 53-59, 10.1016/s0003-2670(98)00395-x.

- A. Alonsomateos; M. Almendralparra; M. Fuentesprieto; Sequential and simultaneous determination of bromate and chlorite (DBPs) by flow techniques: Kinetic differentiation. Talanta 2008, 76, 892-898, 10.1016/j.talanta.2008.04.059.

- C. García De María; K.B. Hueso Domínguez; Simultaneous kinetic determination of 3-hydroxybutyrate and 3-hydroxyvalerate in biopolymer degradation processes. Talanta 2010, 80, 1436-1440, 10.1016/j.talanta.2009.09.049.

- Marco A.Z. Arruda; Elias A.G. Zagatto; Nelson Maniasso; Kinetic determination of cobalt and nickel by flow-injection spectrophotometry. Analytica Chimica Acta 1993, 283, 476-480, 10.1016/0003-2670(93)85259-m.

- Diego Vendramini; Viviane Grassi; Elias A.G. Zagatto; Spectrophotometric flow-injection determination of copper and nickel in plant digests exploiting differential kinetic analysis and multi-site detection. Analytica Chimica Acta 2006, 570, 124-128, 10.1016/j.aca.2006.04.008.

- Paula R. Fortes; Silvia R.P. Meneses; Elias A.G. Zagatto; A novel flow-based strategy for implementing differential kinetic analysis. Analytica Chimica Acta 2006, 572, 316-320, 10.1016/j.aca.2006.05.046.

- P. Linares; M.D.Luque De Castro; M. Valcarcel; Differential kinetic determination of furfural and vanillin by flow injection analysis. Microchemical Journal 1987, 35, 120-124, 10.1016/0026-265x(87)90206-2.

- G. den Boef; Unstable reagents in flow analysis. Analytica Chimica Acta 1989, 216, 289-297, 10.1016/s0003-2670(00)82014-0.

- R.C. Schothorst; G. den Boef; The application of strongly oxidizing agents in flow injection analysis : Part 1. Silver(II). Analytica Chimica Acta 1985, 169, 99-107, 10.1016/s0003-2670(00)86211-x.

- R.C. Schotohrst; J.M. Reijn; H. Poppe; G. den Boef; The application of strongly reducing agents in flow injection analysis: Part 1. Chromium(II) and vanadium(II). Analytica Chimica Acta 1983, 145, 197-201, 10.1016/0003-2670(83)80062-2.

- Willian T. Suarez; Heberth J. Vieira; Orlando Fatibello-Filho; Generation and destruction of unstable reagent in flow injection system: determination of acetylcysteine in pharmaceutical formulations using bromine as reagent. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis 2005, 37, 771-775, 10.1016/j.jpba.2004.11.032.

- Suelle G.F. Assis; Marcelo F. Andrade; Maria C.B.S.M. Montenegro; Boaventura F. Reis; Ana P.S. Paim; Determination of polyphenol content by formation of unstable compound using a mini-pump multicommutation system. Food Analytical Methods 2016, 9, 2261-2269, 10.1007/s12161-016-0411-z.

- Huichang Ma; Jingfu Liu; Flow-injection determination of cyanide by detecting an intemediate of the pyridine-barbituric acid chromgonic reaction. Analytica Chimica Acta 1992, 261, 247-252, 10.1016/0003-2670(92)80198-g.

- Archana Jain; Anupama Chaurasia; Krishna K. Verma; Determination of ascorbic acid in soft drinks, preserved fruit juices and pharmaceuticals by flow injection spectrophotometry: Matrix absorbance correction by treatment with sodium hydroxide. Talanta 1995, 42, 779-787, 10.1016/0039-9140(95)01477-s.

- Fábio R.P. Rocha; Ivo M. Raimundo Jr.; Leonardo S.G. Teixeira; Direct solid-phase optical measurements in flow systems: a review. Analytical Letters 2010, 44, 528-559, 10.1080/00032719.2010.500790.

- Leonardo S.G. Teixeira; Fábio R.P. Rocha; Mauro Korn; Boaventura F. Reis; Sergio L.C. Ferreira; Antonio C.S. Costa; Nickel and zinc determination by flow-injection solid-phase spectrophotometry exploiting different sorption rates. Talanta 2000, 51, 1027-1033, 10.1016/s0039-9140(00)00288-5.

- Leonardo S.G. Teixeira; Fábio R.P. Rocha; A green analytical procedure for sensitive and selective determination of iron in water samples by flow-injection solid-phase spectrophotometry. Talanta 2007, 71, 1507-1511, 10.1016/j.talanta.2006.07.025.

- Claudineia R. Silva; Taciana F. Gomes; Valdemir A.F. Barros; Elias A.G. Zagatto; A multi-purpose flow manifold for the spectrophotometric determination of sulphide, sulphite and ethanol involving gas diffusion: Application to wine and molasses analysis. Talanta 2013, 113, 118-122, 10.1016/j.talanta.2013.03.021.

- Andre F. Oliveira; Joaquim A. Nóbrega; Orlando Fatibello-Filho; Asynchronous merging zones system: spectrophotometric determination of Fe(II) and Fe(III) in pharmaceutical products. Talanta 1999, 49, 505-510, 10.1016/s0039-9140(99)00015-6.

- J.L. Montesinos; J. Alonso; M. del Valle; J.L.F.C. Lima; M. Poch; Mathematical modelling of two-analyte sequential determinations by flow-injection sandwich techniques. Analytica Chimica Acta 1991, 254, 177-187, 10.1016/0003-2670(91)90024-y.

- Jacobus van Staden; Chemical speciation by sequential injection analysis: an overview. Talanta 2004, 64, 1109-1113, 10.1016/j.talanta.2004.05.042.

- Kamil Strzelak; Natalia Rybkowska; Agnieszka Wiśniewska; Robert Koncki; Photometric flow analysis system for biomedical investigations of iron/transferrin speciation in human serum. Analytica Chimica Acta 2017, 995, 43-51, 10.1016/j.aca.2017.10.015.

- Agnieszka Gałuszka; Zdzisław Migaszewski; Jacek Namiesnik; The 12 principles of green analytical chemistry and the SIGNIFICANCE mnemonic of green analytical practices. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2013, 50, 78-84, 10.1016/j.trac.2013.04.010.

- Isela Lavilla; Vanesa Romero; I. Costas; Carlos Bendicho; Greener derivatization in analytical chemistry. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2014, 61, 1-10, 10.1016/j.trac.2014.05.007.

- Eulogio J. Llorent-Martínez; M. L. Fernandez-De Cordova; Antonio Ruiz-Medina; Pilar Ortega-Barrales; Ortega-Barrales Pilar; Reagentless photochemically-induced fluorimetric determination of fipronil by sequential-injection analysis. Analytical Letters 2011, 44, 2606-2616, 10.1080/00032719.2011.553006.

- Sivanildo S. Borges; Rejane M. Frizzarin; Boaventura F. Reis; An automatic flow injection analysis procedure for photometric determination of ethanol in red wine without using a chromogenic reagent. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry 2006, 385, 197-202, 10.1007/s00216-006-0377-6.

- Ana Machado; Graham Marshall; Adriano A. Bordalo; Raquel B. R. Mesquita; A greener alternative for inline nitrate reduction in the sequential injection determination of NOx in natural waters: replacement of cadmium reduction by UV radiation. Analytical Methods 2017, 9, 1876-1884, 10.1039/C7AY00261K.

- Wanessa R. Melchert; Carlos M.C. Infante; Fábio R.P. Rocha; Development and critical comparison of greener flow procedures for nitrite determination in natural waters. Microchemical Journal 2007, 85, 209-213, 10.1016/j.microc.2006.05.010.

- Michio Zenki; Kazuyoshi Minamisawa; Takashi Yokoyama; Clean analytical methodology for the determination of lead with Arsenazo III by cyclic flow-injection analysis. Talanta 2005, 68, 281-286, 10.1016/j.talanta.2005.07.059.

- Kate Grudpan; Supaporn Kradtap Hartwell; Wasin Wongwilai; Supara Grudpan; Somchai Lapanantnoppakhun; Exploiting green analytical procedures for acidity and iron assays employing flow analysis with simple natural reagent extracts. Talanta 2011, 84, 1396-1400, 10.1016/j.talanta.2011.03.090.

- Iolanda C. Vieira; Orlando Fatibello-Filho; Flow injection spectrophotometric determination of total phenols using a crude extract of sweet potato root (Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam.) as enzymatic source. Analytica Chimica Acta 1998, 366, 111-118, 10.1016/s0003-2670(97)00724-1.

- Miguel de la Guardia; Karim D. Khalaf; Vicente Carbonell; Angel Morales-Rubio; Clean analytical method for the determination of propoxur. Analytica Chimica Acta 1995, 308, 462-468, 10.1016/0003-2670(94)00625-v.

- Cláudio C. Oliveira; Raquel P. Sartini; Elias A.G. Zagatto; José L.F.C. Lima; Flow analysis with accuracy assessment. Analytica Chimica Acta 1997, 350, 31-36, 10.1016/s0003-2670(97)00235-3.