| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Małgorzata Piecuch | + 2395 word(s) | 2395 | 2022-01-07 02:30:44 | | | |

| 2 | Peter Tang | Meta information modification | 2395 | 2022-01-14 03:19:26 | | |

Video Upload Options

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory skin disease. Immunological, genetic, and environmental factors, including diet, play a part in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. Metabolic syndrome or its components are frequent co-morbidities in persons with psoriasis. A change of eating habits can improve the quality of life of patients by relieving skin lesions and by reducing the risk of other diseases. A low-energy diet is recommended for patients with excess body weight. Persons suffering from psoriasis should limit the intake of saturated fatty acids and replace them with polyunsaturated fatty acids from the omega-3 family, which have an anti-inflammatory effect. In diet therapy for persons with psoriasis, the introduction of antioxidants such as vitamin A, vitamin C, vitamin E, carotenoids, flavonoids, and selenium is extremely important. Vitamin D supplementation is also recommended.

1. Introduction

-

physical factors (X-rays, subcutaneous and intradermal injections, surgical procedures, vaccinations, tattoos, insect bites, abrasions, burns (including sunburns), acupuncture, UV irradiation);

-

chemical factors (chemical burns, topical treatments, others);

-

skin diseases (rosacea, fungal infections, allergic contact dermatitis);

-

infections (mainly streptococcal pharyngitis, viral infections);

-

stress;

-

medications (β-adrenolytics, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, lithium, terbinafine, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, anti-malarial drugs, tetracyclines, rapid withdrawal of systemic corticosteroids);

-

diet;

-

tobacco smoking;

-

alcohol consumption.

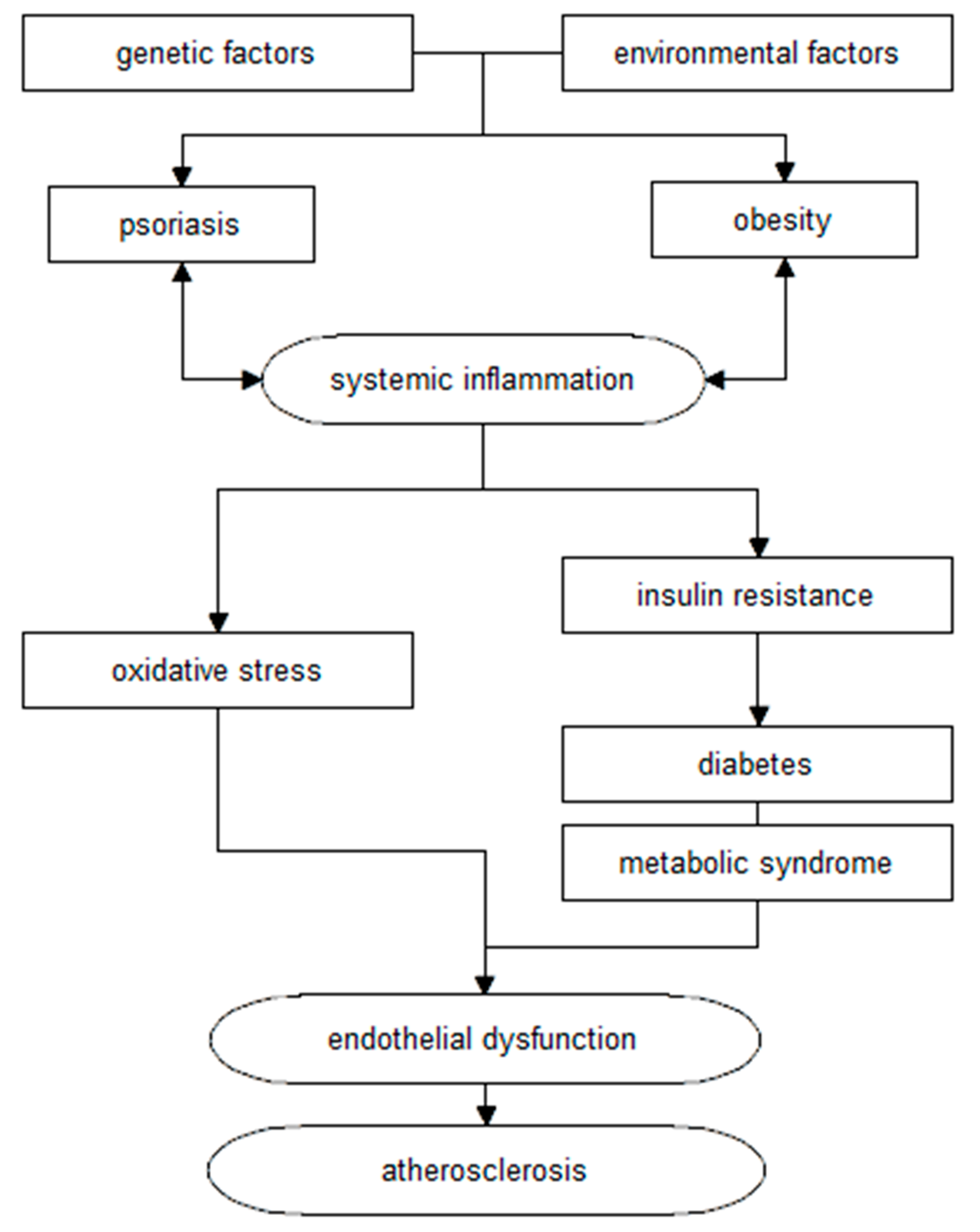

2. Metabolic Syndrome

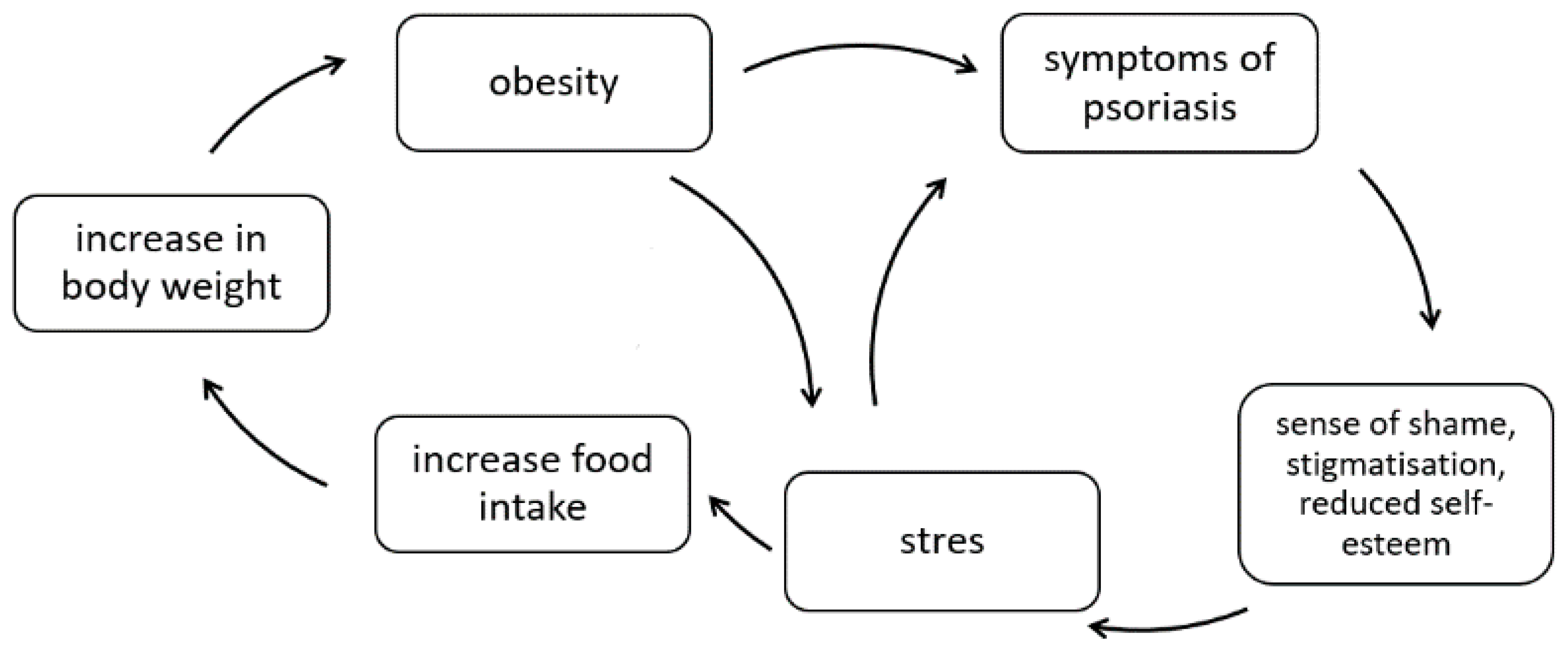

3. Obesity

-

body weight assessment;

-

BMI assessment;

-

assessment of waist/hip ratio (WHR);

-

fasting blood glucose determination at least once a year;

-

more frequent testing for hypertension;

-

determination of serum lipids;

-

determination of serum uric acid and liver enzymes;

-

in patients with other cardiovascular risk factors (e.g., hypertension, obesity), performing an Oral Glucose Tolerance Test (OGTT).

4. Low-Energy Diet in the Treatment of Psoriasis

References

- Tupikowska, M.; Zdrojowy-Welna, A.; Maj, J. Psoriasis as metabolic and cardiovascular risk factor. Pol. Merkur Lek. 2014, 37, 124–127.

- WHO. Global Report on Psoriasis. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/204417 (accessed on 2 October 2021).

- Zuccotti, E.; Oliveri, M.; Girometta, C.; Ratto, D.; Di Iorio, C.; Occhinegro, A.; Rossi, P. Nutritional strategies for psoriasis: Current scientific evidence in clinical trials. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2018, 22, 8537–8551.

- Placek, W.; Mieszczak-Woszczyna, D. Dieta w schorzeniach dermatologicznych (II). Znaczenie kwasów omega-3 w leczeniu łuszczycy. Dermatol. Estet. 2011, 13, 125–131.

- Szczerkowska-Dobosz, A.; Komorowska, O. Łuszczyca i miażdżyca—Związek nieprzypadkowy. Dermatol. Dypl. 2014, 5, 18–23.

- Trojacka, E.; Zaleska, M.; Galus, R. Influence of exogenous and endogenous factors on the course of psoriasis. Pol. Merkur Lek. 2015, 38, 169–173.

- Holmannova, D.; Borska, L.; Andrys, C.; Borsky, P.; Kremlacek, J.; Hamakova, K.; Rehacek, V.; Malkova, A.; Svadlakova, T.; Palicka, V.; et al. The Impact of Psoriasis and Metabolic Syndrome on the Systemic Inflammation and Oxidative Damage to Nucleic Acids. J. Immunol. Res. 2020, 2020, 7352637.

- Polic, M.V.; Miskulin, M.; Smolic, M.; Kralik, K.; Miskulin, I.; Berkovic, M.C.; Curcic, I.B. Psoriasis Severity-A Risk Factor of Insulin Resistance Independent of Metabolic Syndrome. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2018, 15, 1486.

- Kanda, N.; Hoashi, T.; Saeki, H. Nutrition and Psoriasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5405.

- Ni, C.; Chiu, M.W. Psoriasis and comorbidities: Links and risks. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2014, 7, 119–132.

- Baran, A.; Kiluk, P.; Mysliwiec, H.; Flisiak, I. The role of lipids in psoriasis. Prz. Dermatol. 2017, 104, 619–635.

- Gupta, S.; Syrimi, Z.; Hughes, D.M.; Zhao, S.S. Comorbidities in psoriatic arthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatol. Int. 2021, 41, 275–284.

- Choudhary, S.; Pradhan, D.; Pandey, A.; Khan, M.K.; Lall, R.; Ramesh, V.; Puri, P.; Jain, A.K.; Thomas, G. The Association of Metabolic Syndrome and Psoriasis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Study. Endocr. Metab. Immune Disord. Drug Targets 2020, 20, 703–717.

- Antosik, K.; Krzęcio-Nieczyporuk, E.; Kurowska-Socha, B. Diet and nutrition in psoriasis treatment. Hyg. Pub. Health 2017, 52, 131–137.

- Gisondi, P.; Fostini, A.; Fossa, I.; Girolomoni, G.; Targher, G. Psoriasis and the metabolic syndrome. Clin. Dermatol. 2018, 36, 21–28.

- Langan, S.M.; Seminara, N.M.; Shin, D.B.; Troxel, A.B.; Kimmel, S.E.; Mehta, N.N.; Margolis, D.J.; Gelfand, J.M. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in patients with psoriasis: A population-based study in the United Kingdom. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2012, 132, 556–562.

- Yamazaki, F. Psoriasis: Comorbidities. J. Dermatol. 2021, 48, 732–740.

- Atawia, R.T.; Bunch, K.L.; Toque, H.A.; Caldwell, R.B.; Caldwell, R.W. Mechanisms of obesity-induced metabolic and vascular dysfunctions. Front. Biosci. 2019, 24, 890–934.

- Armstrong, A.W.; Harskamp, C.T.; Armstrong, E.J. The association between psoriasis and obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Nutr. Diabetes 2012, 2, e54.

- Snekvik, I.; Smith, C.H.; Nilsen, T.I.L.; Langan, S.M.; Modalsli, E.H.; Romundstad, P.R.; Saunes, M. Obesity, Waist Circumference, Weight Change, and Risk of Incident Psoriasis: Prospective Data from the HUNT Study. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2017, 137, 2484–2490.

- Galluzzo, M.; Talamonti, M.; Perino, F.; Servoli, S.; Giordano, D.; Chimenti, S.; De Simone, C.; Peris, K. Bioelectrical impedance analysis to define an excess of body fat: Evaluation in patients with psoriasis. J. Dermatol. Treat. 2017, 28, 299–303.

- Diniz, M.S.; Bavoso, N.C.; Kakehasi, A.M.; Lauria, M.W.; Soares, M.M.; Pinto, J.M. Assessment of adiposity in psoriatic patients by dual energy X-ray absorptiometry compared to conventional methods. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2016, 91, 150–155.

- Blake, T.; Gullick, N.J.; Hutchinson, C.E.; Barber, T.M. Psoriatic disease and body composition: A systematic review and narrative synthesis. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0237598.

- Barrea, L.; Macchia, P.E.; Di Somma, C.; Napolitano, M.; Balato, A.; Falco, A.; Savanelli, M.C.; Balato, N.; Colao, A.; Savastano, S. Bioelectrical phase angle and psoriasis: A novel association with psoriasis severity, quality of life and metabolic syndrome. J. Transl. Med. 2016, 14, 130.

- Budu-Aggrey, A.; Brumpton, B.; Tyrrell, J.; Watkins, S.; Modalsli, E.H.; Celis-Morales, C.; Ferguson, L.D.; Vie, G.; Palmer, T.; Fritsche, L.G.; et al. Evidence of a causal relationship between body mass index and psoriasis: A mendelian randomization study. PLoS Med. 2019, 16, e1002739.

- Sahi, F.M.; Masood, A.; Danawar, N.A.; Mekaiel, A.; Malik, B.H. Association between Psoriasis and Depression: A Traditional Review. Cureus 2020, 12, e9708.

- Bremner, J.D.; Moazzami, K.; Wittbrodt, M.T.; Nye, J.A.; Lima, B.B.; Gillespie, C.F.; Rapaport, M.H.; Pearce, B.D.; Shah, A.J.; Vaccarino, V. Diet, Stress and Mental Health. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2428.

- Balbás, G.M.; Regaña, M.S.; Millet, P.U. Study on the use of omega-3 fatty acids as a therapeutic supplement in treatment of psoriasis. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2011, 4, 73–77.

- Barrea, L.; Nappi, F.; Di Somma, C.; Savanelli, M.C.; Falco, A.; Balato, A.; Balato, N.; Savastano, S. Environmental Risk Factors in Psoriasis: The Point of View of the Nutritionist. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 743.

- Gołąbek, K.; Regulska-Ilow, B. Dietary support of pharmacological psoriasis treatment. Hyg. Pub. Health 2017, 52, 335–342.

- Jensen, P.; Zachariae, C.; Christensen, R.; Geiker, N.R.; Schaadt, B.K.; Stender, S.; Hansen, P.R.; Astrup, A.; Skov, L. Effect of weight loss on the severity of psoriasis: A randomized clinical study. JAMA Dermatol. 2013, 149, 795–801.

- Jensen, P.; Christensen, R.; Zachariae, C.; Geiker, N.R.; Schaadt, B.K.; Stender, S.; Hansen, P.R.; Astrup, A.; Skov, L. Long-term effects of weight reduction on the severity of psoriasis in a cohort derived from a randomized trial: A prospective observational follow-up study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 104, 259–265.

- Gisondi, P.; Del Giglio, M.; Di Francesco, V.; Zamboni, M.; Girolomoni, G. Weight loss improves the response of obese patients with moderate-to-severe chronic plaque psoriasis to low-dose cyclosporine therapy: A randomized, controlled, investigator-blinded clinical trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 88, 1242–1247.

- Wasiluk, D.; Ostrowska, L.; Stefańska, E. Can an adequate diet be helpful in the treatment of psoriasis vulgaris? Med. Og. Nauki. Zdr. 2012, 18, 405–408.