| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hugo Maruyama | + 3098 word(s) | 3098 | 2021-12-23 03:43:33 | | | |

| 2 | Beatrix Zheng | Meta information modification | 3098 | 2021-12-28 08:00:35 | | |

Video Upload Options

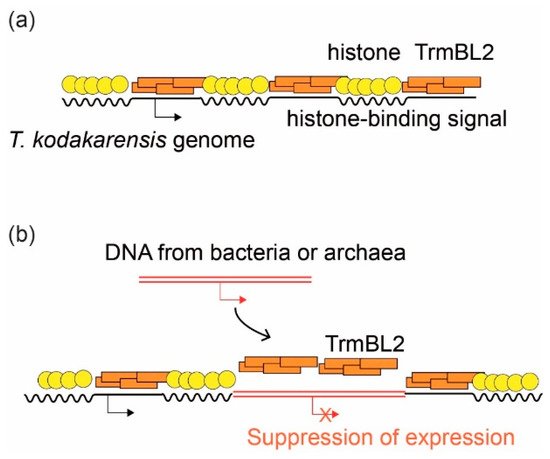

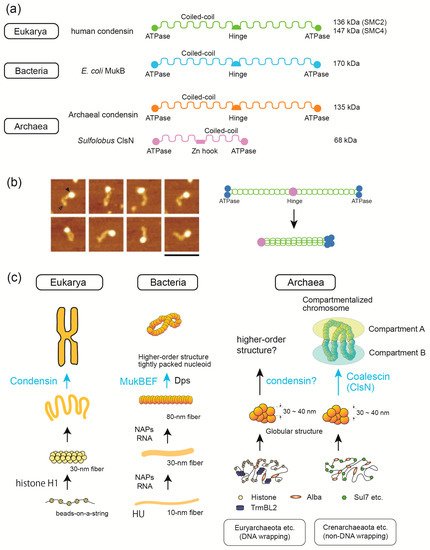

Comparative structural/molecular biology by single-molecule analyses combined with single-cell dissection, mass spectroscopy, and biochemical reconstitution have been powerful tools for elucidating the mechanisms underlying genome DNA folding. All genomes in the three domains of life undergo stepwise folding from DNA to 30–40 nm fibers. Major protein players are histone (Eukarya and Archaea), Alba (Archaea), and HU (Bacteria) for fundamental structural units of the genome. In Euryarchaeota, a major archaeal phylum, either histone or HTa (the bacterial HU homolog) were found to wrap DNA. This finding divides archaea into two groups: those that use DNA-wrapping as the fundamental step in genome folding and those that do not. Archaeal transcription factor-like protein TrmBL2 has been suggested to be involved in genome folding and repression of horizontally acquired genes, similar to bacterial H-NS protein. Evolutionarily divergent SMC proteins contribute to the establishment of higher-order structures. Recent results are presented, including the use of Hi-C technology to reveal that archaeal SMC proteins are involved in higher-order genome folding, and the use of single-molecule tracking to reveal the detailed functions of bacterial and eukaryotic SMC proteins. Here, we highlight the similarities and differences in the DNA-folding mechanisms in the three domains of life.

1. Fundamental Chromosomal/Nucleoid Proteins

1.1. Histone

1.2. Alba

1.3. HU

1.4. Suppression of Horizontally Transferred Genes by Global Regulatory Proteins

1.5. SMC Proteins Are Involved in 3D Structure Formation in the Three Domains of Life

References

- Kathleen Sandman; J. A. Krzycki; B. Dobrinski; R. Lurz; J. N. Reeve; HMf, a DNA-binding protein isolated from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Methanothermus fervidus, is most closely related to histones.. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1990, 87, 5788-5791, 10.1073/pnas.87.15.5788.

- Bram Henneman; Clara Van Emmerik; Hugo van Ingen; Remus T. Dame; Structure and function of archaeal histones. PLOS Genetics 2018, 14, e1007582, 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007582.

- Kathryn M. Stevens; Jacob B. Swadling; Antoine Hocher; Corinna Bang; Simonetta Gribaldo; Ruth A. Schmitz; Tobias Warnecke; Histone variants in archaea and the evolution of combinatorial chromatin complexity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2020, 117, 33384-33395, 10.1073/pnas.2007056117.

- Béatrice Alpha-Bazin; Aurore Gorlas; Arnaud Lagorce; Damien Joulié; Jean-Baptiste Boyer; Murielle Dutertre; Jean-Charles Gaillard; Anne Lopes; Yvan Zivanovic; Alain Dedieu; et al.Fabrice ConfalonieriJean Armengaud Lysine-specific acetylated proteome from the archaeon Thermococcus gammatolerans reveals the presence of acetylated histones. Journal of Proteomics 2020, 232, 104044, 10.1016/j.jprot.2020.104044.

- Hugo Maruyama; Minsang Shin; Toshiyuki Oda; Rie Matsumi; Ryosuke L. Ohniwa; Takehiko Itoh; Katsuhiko Shirahige; Tadayuki Imanaka; Haruyuki Atomi; Shige H. Yoshimura; et al.Kunio Takeyasu Histone and TK0471/TrmBL2 form a novel heterogeneous genome architecture in the hyperthermophilic archaeonThermococcus kodakarensis. Molecular Biology of the Cell 2011, 22, 386-398, 10.1091/mbc.e10-08-0668.

- Shawn P. Laursen; Samuel Bowerman; Karolin Luger; Archaea: The Final Frontier of Chromatin. Journal of Molecular Biology 2020, 433, 166791, 10.1016/j.jmb.2020.166791.

- Hugo Maruyama; Janet C Harwood; Karen M Moore; Konrad Paszkiewicz; Samuel Durley; Hisanori Fukushima; Haruyuki Atomi; Kunio Takeyasu; Nicholas A Kent; An alternative beads‐on‐a‐string chromatin architecture in Thermococcus kodakarensis. EMBO reports 2013, 14, 711-717, 10.1038/embor.2013.94.

- Francesca Mattiroli; Sudipta Bhattacharyya; Pamela N. Dyer; Alison E. White; Kathleen Sandman; Brett W. Burkhart; Kyle R. Byrne; Thomas Lee; Natalie G. Ahn; Thomas J. Santangelo; et al.John N. ReeveKarolin Luger Structure of histone-based chromatin in Archaea. Science 2017, 357, 609-612, 10.1126/science.aaj1849.

- Samuel Bowerman; Jeff Wereszczynski; Karolin Luger; Archaeal chromatin ‘slinkies’ are inherently dynamic complexes with deflected DNA wrapping pathways. eLife 2021, 10, e65587, 10.7554/elife.65587.

- Travis J. Sanders; Fahad Ullah; Alexandra M. Gehring; Brett W. Burkhart; Robert L. Vickerman; Sudili Fernando; Andrew F. Gardner; Asa Ben-Hur; Thomas J. Santangelo; Extended Archaeal Histone-Based Chromatin Structure Regulates Global Gene Expression in Thermococcus kodakarensis. Frontiers in Microbiology 2021, 12, 681150, 10.3389/fmicb.2021.681150.

- Bram Henneman; Thomas B Brouwer; Amanda M Erkelens; Gert-Jan Kuijntjes; Clara van Emmerik; Ramon A van der Valk; Monika Timmer; Nancy C S Kirolos; Hugo van Ingen; John van Noort; et al.Remus T Dame Mechanical and structural properties of archaeal hypernucleosomes. Nucleic Acids Research 2020, 49, 4338-4349, 10.1093/nar/gkaa1196.

- Masako Koyama; Hitoshi Kurumizaka; Structural diversity of the nucleosome. The Journal of Biochemistry 2017, 163, 85-95, 10.1093/jb/mvx081.

- Manish Goyal; Chinmoy Banerjee; Shiladitya Nag; Uday Bandyopadhyay; The Alba protein family: Structure and function. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Proteins and Proteomics 2016, 1864, 570-583, 10.1016/j.bbapap.2016.02.015.

- Niels Laurens; Rosalie P.C. Driessen; Iddo Heller; Daan Vorselen; Maarten C. Noom; Felix J.H. Hol; Malcolm F. White; Remus T. Dame; Gijs J.L. Wuite; Alba shapes the archaeal genome using a delicate balance of bridging and stiffening the DNA. Nature Communications 2012, 3, 1328, 10.1038/ncomms2330.

- Hugo Maruyama; Eloise I. Prieto; Takayuki Nambu; Chiho Mashimo; Kosuke Kashiwagi; Toshinori Okinaga; Haruyuki Atomi; Kunio Takeyasu; Different Proteins Mediate Step-Wise Chromosome Architectures in Thermoplasma acidophilum and Pyrobaculum calidifontis. Frontiers in Microbiology 2020, 11, 1247, 10.3389/fmicb.2020.01247.

- Ryosuke L. Ohniwa; Kazuya Morikawa; Sayaka L. Takeshita; Joongbaek Kim; Toshiko Ohta; Chieko Wada; Kunio Takeyasu; Transcription-coupled nucleoid architecture in bacteria. Genes to Cells 2007, 12, 1141-1152, 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2007.01125.x.

- Ryosuke L. Ohniwa; Hiroki Muchaku; Shinji Saito; Chieko Wada; Kazuya Morikawa; Atomic Force Microscopy Analysis of the Role of Major DNA-Binding Proteins in Organization of the Nucleoid in Escherichia coli. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e72954, 10.1371/journal.pone.0072954.

- Pavla Stojkova; Petra Spidlova; Jiri Stulik; Nucleoid-Associated Protein HU: A Lilliputian in Gene Regulation of Bacterial Virulence. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology 2019, 9, 159, 10.3389/fcimb.2019.00159.

- Kelsey Bettridge; Subhash Verma; Xiaoli Weng; Sankar Adhya; Jie Xiao; Single‐molecule tracking reveals that the nucleoid‐associated protein HU plays a dual role in maintaining proper nucleoid volume through differential interactions with chromosomal DNA. Molecular Microbiology 2020, 115, 12-27, 10.1111/mmi.14572.

- Antoine Hocher; Maria Rojec; Jacob B Swadling; Alexander Esin; Tobias Warnecke; The DNA-binding protein HTa from Thermoplasma acidophilum is an archaeal histone analog. eLife 2019, 8, e52542, 10.7554/elife.52542.

- Dennis G. Searcy; Diana B. Stein; Nucleoprotein subunit structure in an unusual prokaryotic organism: Thermoplasma acidophilum. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Nucleic Acids and Protein Synthesis 1980, 609, 180-195, 10.1016/0005-2787(80)90211-7.

- Purificación López-García; Yvan Zivanovic; Philippe Deschamps; David Moreira; Bacterial gene import and mesophilic adaptation in archaea. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2015, 13, 447-456, 10.1038/nrmicro3485.

- Alexander Wagner; Rachel J. Whitaker; David J. Krause; Jan-Hendrik Heilers; Marleen Van Wolferen; Chris Van Der Does; Sonja-Verena Albers; Mechanisms of gene flow in archaea. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2017, 15, 492-501, 10.1038/nrmicro.2017.41.

- Thøger Krogh; Jakob Møller-Jensen; Christoph Kaleta; Impact of Chromosomal Architecture on the Function and Evolution of Bacterial Genomes. Frontiers in Microbiology 2018, 9, 2019, 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02019.

- Ci Ji Lim; Sin Yi Lee; Linda J. Kenney; Jie Yan; Nucleoprotein filament formation is the structural basis for bacterial protein H-NS gene silencing. Scientific Reports 2012, 2, 509, 10.1038/srep00509.

- Charles J. Dorman; H-NS, the genome sentinel. Nature Reviews Genetics 2006, 5, 157-161, 10.1038/nrmicro1598.

- Jane Wiedenbeck; Frederick M. Cohan; Origins of bacterial diversity through horizontal genetic transfer and adaptation to new ecological niches. FEMS Microbiology Reviews 2011, 35, 957-976, 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2011.00292.x.

- Hugo Maruyama; Nicholas A. Kent; Hiromi Nishida; Taku Oshima; Functions of Archaeal Nucleoid Proteins: Archaeal Silencers are Still Missing. DNA Traffic in the Environment 2019, 1, 29-45, 10.1007/978-981-13-3411-5_2.

- Narasimharao Nalabothula; Liqun Xi; Sucharita Bhattacharyya; Jonathan Widom; Ji-Ping Wang; John N Reeve; Thomas J Santangelo; Yvonne N Fondufe-Mittendorf; Archaeal nucleosome positioning in vivo and in vitro is directed by primary sequence motifs. BMC Genomics 2013, 14, 1-13, 10.1186/1471-2164-14-391.

- Artem Efremov; Yuanyuan Qu; Hugo Maruyama; Ci J. Lim; Kunio Takeyasu; Jie Yan; Transcriptional Repressor TrmBL2 from Thermococcus kodakarensis Forms Filamentous Nucleoprotein Structures and Competes with Histones for DNA Binding in a Salt- and DNA Supercoiling-dependent Manner. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2015, 290, 15770-15784, 10.1074/jbc.m114.626705.

- Filip Husnik; John P. McCutcheon; Functional horizontal gene transfer from bacteria to eukaryotes. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2017, 16, 67-79, 10.1038/nrmicro.2017.137.

- Frank Uhlmann; SMC complexes: from DNA to chromosomes. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 2016, 17, 399-412, 10.1038/nrm.2016.30.

- Thomas J Etheridge; Desiree Villahermosa; Eduard Campillo-Funollet; Alex David Herbert; Anja Irmisch; Adam T Watson; Hung Q Dang; Mark A Osborne; Antony W Oliver; Antony M Carr; et al.Johanne M Murray Live-cell single-molecule tracking highlights requirements for stable Smc5/6 chromatin association in vivo. eLife 2021, 10, e68579, 10.7554/elife.68579.

- Shige H. Yoshimura; Kohji Hizume; Akiko Murakami; Takashi Sutani; Kunio Takeyasu; Mitsuhiro Yanagida; Condensin Architecture and Interaction with DNA: Regulatory Non-SMC Subunits Bind to the Head of SMC Heterodimer. Current Biology 2002, 12, 508-513, 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00719-4.

- Akiko Sakai; Kohji Hizume; Takashi Sutani; Kunio Takeyasu; Mitsuhiro Yanagida; Condensin but not cohesin SMC heterodimer induces DNA reannealing through protein-protein assembly. The EMBO Journal 2003, 22, 2764-2775, 10.1093/emboj/cdg247.

- Iain F. Davidson; Jan-Michael Peters; Genome folding through loop extrusion by SMC complexes. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 2021, 22, 445-464, 10.1038/s41580-021-00349-7.

- Benedikt W. Bauer; Iain F. Davidson; Daniel Canena; Gordana Wutz; Wen Tang; Gabriele Litos; Sabrina Horn; Peter Hinterdorfer; Jan-Michael Peters; Cohesin mediates DNA loop extrusion by a “swing and clamp” mechanism. Cell 2021, 184, 5448-5464.e22, 10.1016/j.cell.2021.09.016.

- Sophie Nolivos; David Sherratt; The bacterial chromosome: architecture and action of bacterial SMC and SMC-like complexes. FEMS Microbiology Reviews 2014, 38, 380-392, 10.1111/1574-6976.12045.

- Sonja Schibany; Luise A K Kleine Borgmann; Thomas C Rösch; Tobias Knust; Maximilian H Ulbrich; Peter L Graumann; Single molecule tracking reveals that the bacterial SMC complex moves slowly relative to the diffusion of the chromosome. Nucleic Acids Research 2018, 46, 7805-7819, 10.1093/nar/gky581.

- Sonja Schibany; Rebecca Hinrichs; Rogelio Hernandez-Tamayo; Peter L. Graumann; The Major Chromosome Condensation Factors Smc, HBsu, and Gyrase in Bacillus subtilis Operate via Strikingly Different Patterns of Motion. mSphere 2020, 5, e00817-e00820, 10.1128/msphere.00817-20.

- Frank Bürmann; Louise F.H. Funke; Jason W. Chin; Jan Löwe; Cryo-EM structure of MukBEF reveals DNA loop entrapment at chromosomal unloading sites. Molecular Cell 2021, 81, 4891-4906.e8, 10.1016/j.molcel.2021.10.011.

- Tatsuya Hirano; Condensin-Based Chromosome Organization from Bacteria to Vertebrates. Cell 2016, 164, 847-857, 10.1016/j.cell.2016.01.033.

- Naomichi Takemata; Rachel Y. Samson; Stephen D. Bell; Physical and Functional Compartmentalization of Archaeal Chromosomes. Cell 2019, 179, 165-179.e18, 10.1016/j.cell.2019.08.036.

- Charlotte Cockram; Agnès Thierry; Aurore Gorlas; Roxane Lestini; Romain Koszul; Euryarchaeal genomes are folded into SMC-dependent loops and domains, but lack transcription-mediated compartmentalization. Molecular Cell 2020, 81, 459-472.e10, 10.1016/j.molcel.2020.12.013.