| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Andrew John Simkin | + 10201 word(s) | 10201 | 2021-11-02 05:18:34 | | | |

| 2 | Catherine Yang | -4784 word(s) | 5417 | 2021-11-03 01:50:16 | | |

Video Upload Options

Carotenoid-derived apocarotenoids (CDCs) are formed by the oxidative cleavage of carbon–carbon double bonds in the carotenoid backbones either by carotenoid cleavage enzymes (CCDs) or via the exposure of carotenoids to ROS. Many of these apocarotenoids play key regulatory roles in plant development as growth simulators and inhibitors, signalling molecules, including as abscisic acid and strigolactones, and have roles in plant defence against pathogens and herbivores. Others act as flavour and aroma compounds in fruit pericarp, flowers and seeds. The diverse variety of carotenoids (+700) means that the potential apocarotenoid products represent a significant number of natural compounds.

1. Apocarotenoid Biosynthesis is Planta

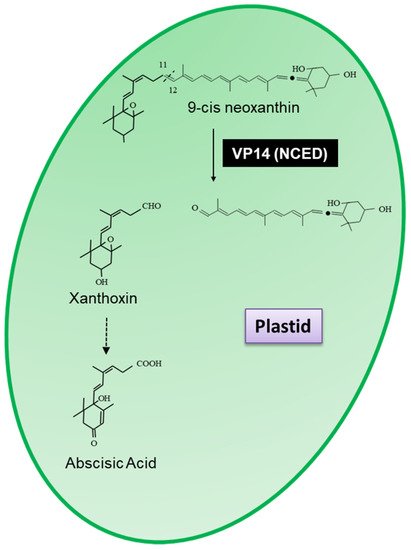

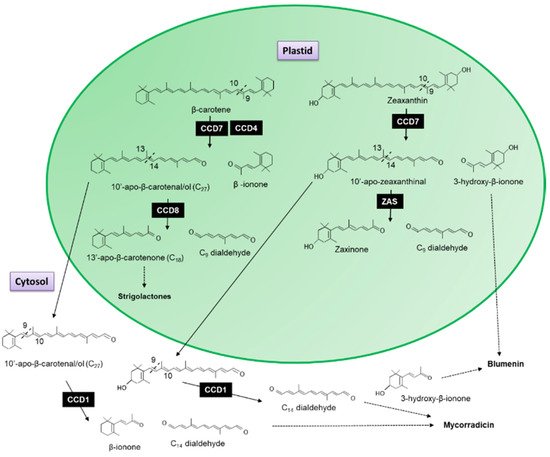

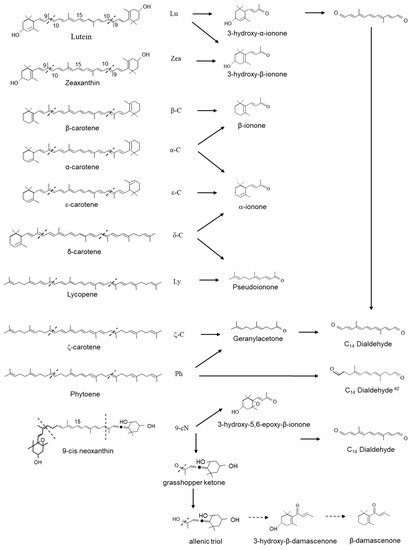

Tan et al. [5] identified nine members of the VP14 family in Arabidopsis, five of which have been shown to cleave neoxanthin at the 11,12 double bond and have thus been renamed as neoxanthin cleavage dioxygenases (NCED2, NCED3, NCED5, NCED6(VP14) and NCED9). These enzymes have been extensively studied and are involved in the biosynthesis of the phytohormone abscisic acid (ABA). ABA regulates plant growth, development and stress responses and plays essential roles in multiple physiological processes, including leaf senescence, osmotic regulation, stomatal closure, bud dormancy, root formation, seed germination and growth inhibition among others. The four remaining NCED were shown to cleave a variety of carotenoids generating a variety of (di)aldehydes and ketones and were renamed carotenoid cleavage dioxygenases/oxygenases (CCD1 (EC.1.13.11.71), CCD4 (EC.1.13.11.n4), CCD7 (EC.1.13.11.68) and CCD8 (EC.1.13.11.69)).

The recombinant CCD7 protein from Arabidopsis exhibited a 9′-10′ asymmetrical cleavage activity converting β-carotene into β-ionone (9-apo-β-caroten-9-one) and 10-apo-β-carotenal (C27 compound; Figure 2) [5]. When the AtCCD8 gene was expressed in Escherichia coli with AtCCD7, the 10-apo-β-carotenal was subsequently cleaved into 13-apo-β-carotenone and a C9 dialdehyde [5]. Since no cleavage activity has been associated with CCD8 when it has been expressed in carotenoid accumulating E. coli lines to date, Schwartz et al. [5] concluded that CCD8 functions as an apocarotenoid cleavage enzyme working sequential with CCD7 as the first steps in the formation of 13-apo-β-carotenone.

2. Carotenoid Cleavage Dioxygenase 1 (CCD1) Enzymes Cleave a Broad Category of Carotenoids and Apocarotenoids at Multiple Double Bonds in the Cytosol

Finally, we also cannot exclude photooxidation as an additional mechanism for the formation of 9′10(9′10′) CDCs β-ionone, pseudoionone, geranylacetone or any of the 5,6(5′6′) and 7,8(7′8′) CDCs generated by the activity of CCD1. It should be noted that the formation of β-ionone from β-carotene by free radical-mediated cleavage of the 9–10 bond has been demonstrated in vitro [51]. In pepper leaves, natural oxidative turnover accounts for as much as 1 mg of carotenoids day-1 g-1 DW [52]. During tomato fruit ripening, carotenoids concentration increases by 10- and 14-fold, mainly due to the accumulation of lycopene [53]. Given the overall quantity of carotenoids that accumulate during fruit ripening, the rates of CDC emission remain very low.

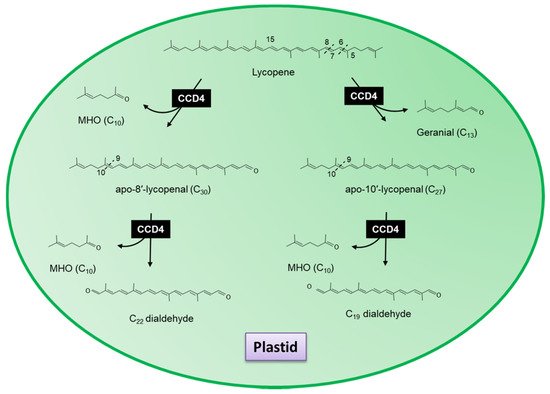

3. Carotenoid Cleavage Dioxygenase 4

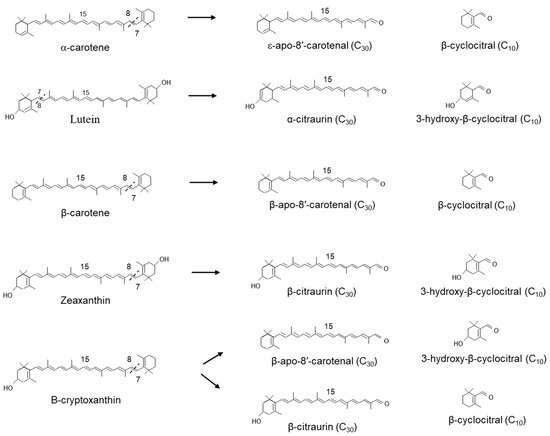

Related work by Rodrigo et al. in the Washington Navel sweet orange (C. sinensis L. Osbeck), Clemenules mandarin (C. clementina), In silico data mining identified five CCD4-type genes in Citrus. One of these genes, CCD4b1, was expressed in different Citrus species in a pattern correlating with the accumulation of β-citraurin. In contrast to the activity identified for CitCCD4, CCD4b1 was also shown to cleave β-carotene into β-apo-8′-carotenal and β-cyclocitral (Figure 6); α-carotene into one single C30 product, ε-apo-8′-carotenal and β-cyclocitral. When lutein was used as a substrate, only α-citraurin (3-OH-8′-apo-ε-carotenal) was identified, suggesting that 3-hydroxy-β-cyclocitral is also formed. In this instance, Rodrigo et al. showed that CCD4b1 cleaves carotenoid structures with an ε-ring but only on the extremity containing the β-ring. These C30 products of lutein, α-carotene and lycopene are not detected in Citrus extracts, which is not unexpected, as lutein and α-carotene are typical only found in green fruits.

4. Novel Carotenoid Cleavage Dioxygenases

5. Apocarotenoids Are Important to Flavour and Aroma

6. Apocarotenoids Are Important Therapeutical Compounds

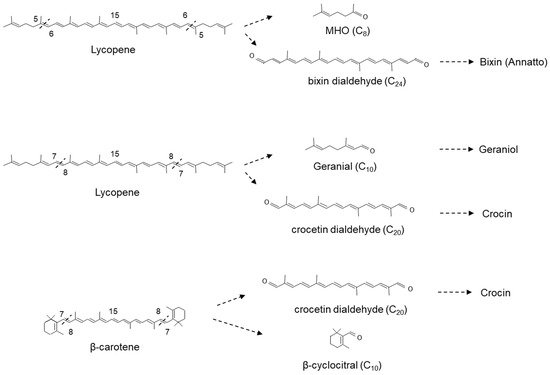

6.1. Bixin

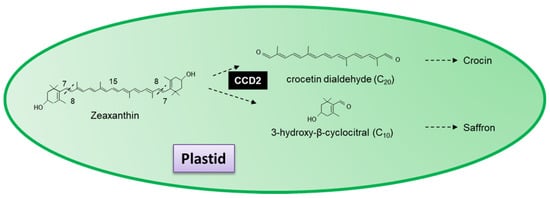

6.2. Saffron and Crocetin

6.3. Carotenoid-Derived Ionones

7. Apocarotenoids Have Roles in Plant Development and Defense

7.1. Apocarotenoids Promote Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Symbiosis and Have Antimicrobial Activities

7.2. Apocarotenoids Attract and Repel Insects

7.3. Developmental Roles of Apocarotenoids

References

- Buttery, R.G.; Teranishi, R.; Ling, L.C.; Flath, R.A.; Stern, D.J. Quantitative studies on origins of fresh tomato aroma volatiles. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1988, 36, 1247–1250.

- Bouvier, F.; Isner, J.-C.; Dogbo, O.; Camara, B. Oxidative tailoring of carotenoids: A prospect towards novel functions in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2005, 10, 187–194.

- Tan, B.C.; Schwartz, S.H.; Zeevaart, J.A.D.; McCarty, D.R. Genetic control of abscisic acid biosynthesis in maize. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 12235–12240.

- Schwartz, S.H.; Tan, B.C.; Gage, D.A.; Zeevaart, J.A.D.; McCarty, D.R. Specific Oxidative Cleavage of Carotenoids by VP14 of Maize. Science 1997, 276, 1872–1874.

- Schwartz, S.H.; Qin, X.; Loewen, M.C. The biochemical characterization of two carotenoid cleavage enzymes from Arabidopsis indicates that a carotenoid-derived compound inhibits lateral branching. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 46940–46945.

- Jia, K.P.; Baz, L.; Al-Babili, S. From carotenoids to strigolactones. J. Exp. Bot. 2018, 69, 2189–2204.

- Aliche, E.B.; Screpanti, C.; De Mesmaeker, A.; Munnik, T.; Bouwmeester, H.J. Science and application of strigolactones. New Phytol. 2020, 227, 1001–1011.

- Waters, M.T.; Gutjahr, C.; Bennett, T.; Nelson, D.C. Strigolactone Signaling and Evolution. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2017, 68, 291–322.

- Dun, E.A.; Brewer, P.B.; Beveridge, C.A. Strigolactones: Discovery of the elusive shoot branching hormone. Trends Plant Sci. 2009, 14, 364–372.

- Wang, J.Y.; Haider, I.; Jamil, M.; Fiorilli, V.; Saito, Y.; Mi, J.; Baz, L.; Kountche, B.A.; Jia, K.-P.; Guo, X.; et al. The apocarotenoid metabolite zaxinone regulates growth and strigolactone biosynthesis in rice. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 810.

- Simkin, A.J.; Schwartz, S.H.; Auldridge, M.; Taylor, M.G.; Klee, H.J. The tomato carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase 1 genes contribute to the formation of the flavor volatiles beta-ionone, pseudoionone, and geranylacetone. Plant J. 2004, 40, 882–892.

- Auldridge, M.E.; Block, A.; Vogel, J.T.; Dabney-Smith, C.; Mila, I.; Bouzayen, M.; Magallanes-Lundback, M.; DellaPenna, D.; McCarty, D.R.; Klee, H.J. Characterization of three members of the Arabidopsis carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase family demonstrates the divergent roles of this multifunctional enzyme family. Plant J. 2006, 45, 982–993.

- Froehlich, J.; Itoh, A.; Howe, G. Tomato allene oxide synthase and fatty acid hydroperoxide lyase, two cytochrome P450s involved in oxylipin metabolism, are targeted to different membranes of chloroplast envelope. Plant Physiol. 2001, 125, 306–317.

- Block, M.A.; Dorne, A.; Joyard, J.; Douce, R. Preparation and characterization of membrane fractions enriched in outer and inner envelope membranes from spinach chloroplasts. J. Biol. Chem. 1983, 258, 13281–13286.

- Markwell, J.; Bruce, B.; Keegstra, K. Isolation of a carotenoid-containing sub-membrane particle from the chloroplastic envelope outer membrane of pea (Pisum sativum). J. Biol. Chem. 1992, 267, 13933–13937.

- Havaux, M. Carotenoids as membrane stabilisers in chloroplasts. Trends Plant Sci. 1998, 3, 147–151.

- Wang, Y.; Ding, G.; Gu, T.; Ding, J.; Li, Y. Bioinformatic and expression analyses on carotenoid dioxygenase genes in fruit development and abiotic stress responses in Fragaria vesca. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2017, 292, 895–907.

- Simkin, A.J.; Underwood, B.A.; Auldridge, M.; Loucas, H.M.; Shibuya, K.; Schmelz, E.; Clark, D.G.; Klee, H.J. Circadian regulation of the PhCCD1 carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase controls emission of beta-ionone, a fragrance volatile of petunia flowers. Plant Physiol. 2004, 136, 3504–3514.

- Cheng, L.; Huang, N.; Jiang, S.; Li, K.; Zhuang, Z.; Wang, Q.; Lu, S. Cloning and functional characterization of two carotenoid cleavage dioxygenases for ionone biosynthesis in chili pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) fruits. Sci. Hortic. 2021, 288, 110368.

- Simkin, A.J.; Moreau, H.; Kuntz, M.; Pagny, G.; Lin, C.; Tanksley, S.; McCarthy, J. An investigation of carotenoid biosynthesis in Coffea canephora and Coffea arabica. J. Plant Physiol. 2008, 165, 1087–1106.

- Simkin, A.J.; Kuntz, M.; Moreau, H.; McCarthy, J. Carotenoid profiling and the expression of carotenoid biosynthetic genes in developing coffee grain. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2010, 48, 434–442.

- Yahyaa, M.; Bar, E.; Dubey, N.K.; Meir, A.; Davidovich-Rikanati, R.; Hirschberg, J.; Aly, R.; Tholl, D.; Simon, P.W.; Tadmor, Y.; et al. Formation of Norisoprenoid Flavor Compounds in Carrot (Daucus carota L.) Roots: Characterization of a Cyclic-Specific Carotenoid Cleavage Dioxygenase 1 Gene. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 12244–12252.

- Ilg, A.; Beyer, P.; Al-Babili, S. Characterization of the rice carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase 1 reveals a novel route for geranial biosynthesis. FEBS J. 2009, 276, 736–747.

- Ibdah, M.; Azulay, Y.; Portnoy, V.; Wasserman, B.; Bar, E.; Meir, A.; Burger, Y.; Hirschberg, J.; Schaffer, A.A.; Katzir, N.; et al. Functional characterization of CmCCD1, a carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase from melon. Phytochemistry 2006, 67, 1579–1589.

- Nawade, B.; Shaltiel-Harpaz, L.; Yahyaa, M.; Bosamia, T.C.; Kabaha, A.; Kedoshim, R.; Zohar, M.; Isaacson, T.; Ibdah, M. Analysis of apocarotenoid volatiles during the development of Ficus carica fruits and characterization of carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase genes. Plant Sci. 2020, 290, 110292.

- Timmins, J.J.B.; Kroukamp, H.; Paulsen, I.T.; Pretorius, I.S. The Sensory Significance of Apocarotenoids in Wine: Importance of Carotenoid Cleavage Dioxygenase 1 (CCD1) in the Production of β-Ionone. Molecules 2020, 25, 2779.

- Mathieu, S.; Terrier, N.; Procureur, J.; Bigey, F.; Günata, Z. A Carotenoid Cleavage Dioxygenase from Vitis vinifera L.: Functional characterization and expression during grape berry development in relation to C13-norisoprenoid accumulation. J. Exp. Bot. 2005, 56, 2721–2731.

- Lashbrooke, J.G.; Young, P.R.; Dockrall, S.J.; Vasanth, K.; Vivier, M.A. Functional characterisation of three members of the Vitis vinifera L. carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase gene family. BMC Plant Biol. 2013, 13, 156.

- Zhou, X.-T.; Jia, L.-D.; Duan, M.-Z.; Chen, X.; Qiao, C.-L.; Ma, J.-Q.; Zhang, C.; Jing, F.-Y.; Zhang, S.-S.; Yang, B.; et al. Genome-wide identification and expression profiling of the carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase (CCD) gene family in Brassica napus L. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0238179.

- Huang, F.-C.; Horváth, G.; Molnár, P.; Turcsi, E.; Deli, J.; Schrader, J.; Sandmann, G.; Schmidt, H.; Schwab, W. Substrate promiscuity of RdCCD1, a carotenoid cleavage oxygenase from Rosa damascena. Phytochemistry 2009, 70, 457–464.

- Schwartz, S.H.; Qin, X.; Zeevaart, J.A. Characterization of a novel carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase from plants. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 25208–25211.

- Vogel, J.T.; Tan, B.-C.; McCarty, D.R.; Klee, H.J. The Carotenoid Cleavage Dioxygenase 1 Enzyme Has Broad Substrate Specificity, Cleaving Multiple Carotenoids at Two Different Bond Positions. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 11364–11373.

- Schmidt, H.; Kurtzer, R.; Eisenreich, W.; Schwab, W. The carotenase AtCCD1 from Arabidopsis thaliana is a dioxygenase. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 9845–9851.

- Mathieu, S.; Bigey, F.; Procureur, J.; Terrier, N.; Günata, Z. Production of a recombinant carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase from grape and enzyme assay in water-miscible organic solvents. Biotechnol. Lett. 2007, 29, 837–841.

- Suzuki, M.; Matsumoto, S.; Mizoguchi, M.; Hirata, S.; Takagi, K.; Hashimoto, I.; Yamano, Y.; Ito, M.; Fleischmann, P.; Winterhalter, P.; et al. Identification of (3S, 9R)- and (3S, 9S)-megastigma-6,7-dien-3,5,9-triol 9-O-beta-D-glucopyranosides as damascenone progenitors in the flowers of Rosa damascena. Mill. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2002, 66, 2692–2697.

- Bezman, Y.; Bilkis, I.; Winterhalter, P.; Fleischmann, P.; Rouseff, R.L.; Baldermann, S.; Naim, M. Thermal oxidation of 9′-cis-neoxanthin in a model system containing peroxyacetic acid leads to the potent odorant beta-damascenone. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 9199–9206.

- Skouroumounis, G.; Massy-Westropp, R.; Sefton, M.; Williams, P. Precursors of damascenone in fruit juices. Tetrahedron. Lett. 1992, 33, 3533–3536.

- Carballo-Uicab, V.M.; Cárdenas-Conejo, Y.; Vallejo-Cardona, A.A.; Aguilar-Espinosa, M.; Rodríguez-Campos, J.; Serrano-Posada, H.; Narváez-Zapata, J.A.; Vázquez-Flota, F.; Rivera-Madrid, R. Isolation and functional characterization of two dioxygenases putatively involved in bixin biosynthesis in annatto (Bixa orellana L.). PeerJ 2019, 7, e7064.

- Cárdenas-Conejo, Y.; Carballo-Uicab, V.; Lieberman, M.; Aguilar-Espinosa, M.; Comai, L.; Rivera-Madrid, R. De novo transcriptome sequencing in Bixa orellana to identify genes involved in methylerythritol phosphate, carotenoid and bixin biosynthesis. BMC Genom. 2015, 16, 877.

- Rodríguez-Ávila, N.L.; Narváez-Zapata, J.A.; Ramírez-Benítez, J.E.; Aguilar-Espinosa, M.L.; Rivera-Madrid, R. Identification and expression pattern of a new carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase gene member from Bixa orellana. J. Exp. Bot. 2011, 62, 5385–5395.

- Simkin, A.J.; Miettinen, K.; Claudel, P.; Burlat, V.; Guirimand, G.; Courdavault, V.; Papon, N.; Meyer, S.; Godet, S.; St-Pierre, B.; et al. Characterization of the plastidial geraniol synthase from Madagascar periwinkle which initiates the monoterpenoid branch of the alkaloid pathway in internal phloem associated parenchyma. Phytochemistry 2013, 85, 36–43.

- Lewis, W.D.; Lilly, S.; Jones, K.L. Lymphoma: Diagnosis and Treatment. Am. Fam. Physician 2020, 101, 34–41.

- Floss, D.S.; Schliemann, W.; Schmidt, J.; Strack, D.; Walter, M.H. RNA Interference-Mediated Repression of MtCCD1 in Mycorrhizal Roots of Medicago truncatula Causes Accumulation of C27 Apocarotenoids, Shedding Light on the Functional Role of CCD1. Plant Physiol. 2008, 148, 1267–1282.

- Floss, D.S.; Walter, M.H. Role of carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase 1 (CCD1) in apocarotenoid biogenesis revisited. Plant Signal. Behav. 2009, 4, 172–175.

- Baldwin, E.A.; Scott, J.W.; Shewmaker, C.K.; Schuch, W. Flavor Trivia and Tomato Aroma: Biochemistry and Possible Mechanisms for Control of Important Aroma Components. Hort. Sci. 2000, 35, 1013–1022.

- Buttery, R.G.; Teranishi, R.; Ling, L.C.; Turnbaugh, J.G. Quantitative and sensory studies on tomato paste volatiles. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1990, 38, 336–340.

- Huang, F.-C.; Molnár, P.; Schwab, W. Cloning and functional characterization of carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase 4 genes. J. Exp. Bot. 2009, 60, 3011–3022.

- Rubio, A.; Rambla, J.L.; Santaella, M.; Gomez, M.D.; Orzaez, D.; Granell, A.; Gomez-Gomez, L. Cytosolic and plastoglobule-targeted carotenoid dioxygenases from Crocus sativus are both involved in beta-ionone release. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 24816–24825.

- Rottet, S.; Devillers, J.; Glauser, G.; Douet, V.; Besagni, C.; Kessler, F. Identification of Plastoglobules as a Site of Carotenoid Cleavage. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1855.

- Cunningham, F.X.; Gantt, E. A portfolio of plasmids for identification and analysis of carotenoid pathway enzymes: Adonis aestivalis as a case study. Photosynth. Res. 2007, 92, 245–259.

- Ohmiya, A.; Kishimoto, S.; Aida, R.; Yoshioka, S.; Sumitomo, K. Carotenoid Cleavage Dioxygenase (CmCCD4a) Contributes to White Color Formation in Chrysanthemum Petals. Plant Physiol. 2006, 142, 1193–1201.

- Ohmiya, A.; Sumitomo, K.; Aida, R. Yellow jimba: Suppression of carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase (CmCCD4a) expression turns white Chrysanthemum petals yellow. J. Jpn. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2009, 78, 450–455.

- Brandi, F.; Bar, E.; Mourgues, F.; Horváth, G.; Turcsi, E.; Giuliano, G.; Liverani, A.; Tartarini, S.; Lewinsohn, E.; Rosati, C. Study of ‘Redhaven’ peach and its white-fleshed mutant suggests a key role of CCD4 carotenoid dioxygenase in carotenoid and norisoprenoid volatile metabolism. BMC Plant Biol. 2011, 11, 24.

- Ma, G.; Zhang, L.; Matsuta, A.; Matsutani, K.; Yamawaki, K.; Yahata, M.; Wahyudi, A.; Motohashi, R.; Kato, M. Enzymatic Formation of β-Citraurin from β-Cryptoxanthin and Zeaxanthin by Carotenoid Cleavage Dioxygenase4 in the Flavedo of Citrus Fruit. Plant Physiol. 2013, 163, 682–695.

- Rodrigo, M.J.; Alquézar, B.; Alós, E.; Medina, V.; Carmona, L.; Bruno, M.; Al-Babili, S.; Zacarías, L. A novel carotenoid cleavage activity involved in the biosynthesis of Citrus fruit-specific apocarotenoid pigments. J. Exp. Bot. 2013, 64, 4461–4478.

- Yamagishi, M.; Kishimoto, S.; Nakayama, M. Carotenoid composition and changes in expression of carotenoid biosynthetic genes in tepals of Asiatic hybrid lily. Plant Breed. 2010, 129, 100–107.

- Frusciante, S.; Diretto, G.; Bruno, M.; Ferrante, P.; Pietrella, M.; Prado-Cabrero, A.; Rubio-Moraga, A.; Beyer, P.; Gomez-Gomez, L.; Al-Babili, S.; et al. Novel carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase catalyzes the first dedicated step in saffron crocin biosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 12246–12251.

- Ahrazem, O.; Rubio-Moraga, A.; Berman, J.; Capell, T.; Christou, P.; Zhu, C.; Gómez-Gómez, L. The carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase CCD2 catalysing the synthesis of crocetin in spring crocuses and saffron is a plastidial enzyme. New Phytol. 2016, 209, 650–663.

- Eugster, C.H.; Hürlimann, H.; Leuenberger, H.J. Crocetindialdehyd und Crocetinhalbaldehyd als Blütenfarbstoffe von Jacquinia angustifolia. Helv. Chim. Acta 1969, 52, 89–90.

- Tandon, J.S.; Katti, S.B.; Rüedi, P.; Eugster, C.H. Crocetin-dialdehyde from Coleus forskohlii BRIQ., Labiatae. Helv. Chim. Acta 1979, 62, 2706–2707.

- Zhong, Y.; Pan, X.; Wang, R.; Xu, J.; Guo, J.; Yang, T.; Zhao, J.; Nadeem, F.; Liu, X.; Shan, H.; et al. ZmCCD10a Encodes a Distinct Type of Carotenoid Cleavage Dioxygenase and Enhances Plant Tolerance to Low Phosphate. Plant Physiol. 2020, 184, 374–392.

- Walter, M.H.; Fester, T.; Strack, D. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi induce the non-mevalonate methylerythritol phosphate pathway of isoprenoid biosynthesis correlated with accumulation of the ‘yellow pigment’ and other apocarotenoids. Plant J. 2000, 21, 571–578.

- Walter, M.H.; Floss, D.S.; Strack, D. Apocarotenoids: Hormones, mycorrhizal metabolites and aroma volatiles. Planta 2010, 232, 1–17.

- Buttery, R.G.; Seifert, R.M.; Guadagni, D.G.; Ling, L.C. Characterization of additional volatile components of tomato. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1971, 19, 524–529.

- Buttery, R.G.; Teranishi, R.; Ling, L.C. Fresh tomato aroma volatiles: A quantitative study. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1987, 35, 540–544.

- Baldwin, E.A.; Nisperos-Carriedo, M.O.; Baker, R.; Scott, J.W. Quantitative analysis of flavor parameters in six Florida tomato cultivars (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill). J. Agric. Food Chem. 1991, 39, 1135–1140.

- Kjeldsen, F.; Christensen, L.P.; Edelenbos, M. Changes in Volatile Compounds of Carrots (Daucus carota L.) during Refrigerated and Frozen Storage. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 5400–5407.

- Lutz, A.; Winterhalter, P. Bio-oxidative cleavage of carotenoids: Important route to physiological active plant constituents. Tetrahedron Lett. 1992, 33, 5169–5172.

- Winterhalter, P.; Schreier, P. The generation of norisoprenoid volatiles in starfruit (Averrhoa carambola L.): A review. Food Rev. Int. 1995, 11, 237–254.

- Mahattanatawee, K.; Rouseff, R.; Valim, M.F.; Naim, M. Identification and Aroma Impact of Norisoprenoids in Orange Juice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 393–397.

- Lewinsohn, E.; Sitrit, Y.; Bar, E.; Azulay, Y.; Meir, A.; Zamir, D.; Tadmor, Y. Carotenoid pigmentation affects the volatile composition of tomato and watermelon fruits, as revealed by comparative genetic analyses. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 3142–3148.

- Oyedeji, A.O.; Ekundayo, O.; Koenig, W.A. Essential Oil Composition of Lawsonia inermis L. Leaves from Nigeria. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2005, 17, 403–404.

- Viuda-Martos, M.; Sendra, E.; Pérez-Alvarez, J.A.; Fernández-López, J.; Amensour, M.; Abrini, J. Identification of Flavonoid Content and Chemical Composition of the Essential Oils of Moroccan Herbs: Myrtle (Myrtus communis L.), Rockrose (Cistus ladanifer L.) and Montpellier cistus (Cistus monspeliensis L.). J. Essent. Oil Res. 2011, 23, 1–9.

- Cooper, C.M.; Davies, N.W.; Menary, R.C. C-27 Apocarotenoids in the Flowers of Boronia megastigma (Nees). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 2384–2389.

- Paparella, A.; Shaltiel-Harpaza, L.; Ibdah, M. β-Ionone: Its Occurrence and Biological Function and Metabolic Engineering. Plants 2021, 10, 754.

- Demole, E.; Enggist, P.; Saeuberli, U.; Stoll, M.; Kováts, E.S. Structure et synthèse de la damascénone (triméthyl-2,6,6-trans-crotonoyl-1-cyclohexadiène-1,3), constituant odorant de l’essence de rose bulgare (rosa damascena Mill. Helv. Chim. Acta 1970, 53, 541–551.

- Renold, W.; Naf-Muller, R.; Keller, U.; Wilhelm, B.; Ohloff, G. Investigation of tea aroma. Part 1. New volatile black tea constituents. Helv. Chim. Acta 1974, 57, 1301–1308.

- Kumazawa, K.; Masuda, H. Change in the flavor of black tea drink during heat processing. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001, 49, 3304–3309.

- Buttery, R.G.; Teranishi, R.; Ling, L.C. Identification of damascenone in tomato volatiles. Chem. Ind. 1988, 7, 238.

- Roberts, D.; Morehai, A.P.; Acree, T.E. Detection and partialcharacterization of eight â-damascenone precursors in apples (Malus domestica Borkh. Cv. Empire). J. Agric. Food Chem. 1994, 42, 345–349.

- Lin, J.; Rouseff, R.L.; Barros, S.; Naim, M. Aroma Composition Changes in Early Season Grapefruit Juice Produced from Thermal Concentration. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 813–819.

- Winterhalter, P.; Gök, R. TDN and β-Damascenone: Two Important Carotenoid Metabolites in Wine. In Carotenoid Cleavage Products; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; Volume 1134, pp. 125–137.

- Sefton, M.A.; Skouroumounis, G.K.; Elsey, G.M.; Taylor, D.K. Occurrence, Sensory Impact, Formation, and Fate of Damascenone in Grapes, Wines, and Other Foods and Beverages. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 9717–9746.

- Schreier, P.; Drawert, F.; Schmid, M. Changes in the composition of neutral volatile components during the production of apple brandy. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1978, 29, 728–736.

- Chevance, F.; Guyot-Declerck, C.; Dupont, J.; Collin, S. Investigation of the beta-damascenone level in fresh and aged commercial beers. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 3818–3821.

- Guido, L.F.; Carneiro, J.R.; Santos, J.R.; Almeida, P.J.; Rodrigues, J.A.; Barros, A.A. Simultaneous determination of E-2-nonenal and beta-damascenone in beer by reversed-phase liquid chromatography with UV detection. J. Chromatogr. A 2004, 1032, 17–22.

- Poisson, L.; Schieberle, P. Characterization of the Most Odor-Active Compounds in an American Bourbon Whisky by Application of the Aroma Extract Dilution Analysis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 5813–5819.

- Czerny, M.; Grosch, W. Potent odorants of raw Arabica coffee. Their changes during roasting. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000, 48, 868–872.

- Meng, N.; Yan, G.-L.; Zhang, D.; Li, X.-Y.; Duan, C.-Q.; Pan, Q.-H. Characterization of two Vitis vinifera carotenoid cleavage dioxygenases by heterologous expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2019, 46, 6311–6323.

- Baldwin, E.A.; Scott, J.W.; Einstein, M.A.; Malundo, T.M.M.; Carr, B.T.; Shewfelt, R.L.; Tandon, K.S. Relationship between Sensory and Instrumental Analysis for Tomato Flavor. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 1998, 123, 906.

- Tandon, K.; Baldwin, E.A.; Shewfelt, R. Aroma perception of individual volatile compounds in fresh tomatoes (Lycopersicon esculentum, Mill.) as affected by the medium of evaluation. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2000, 20, 261–268.

- Pino, J.A.; Mesa, J.; Muñoz, Y.; Martí, M.P.; Marbot, R. Volatile Components from Mango (Mangifera indica L.) Cultivars. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 2213–2223.

- Knudsen, J.T.; Eriksson, R.; Gershenzon, J.; Ståhl, B. Diversity and Distribution of Floral Scent. Bot. Rev. 2006, 72, 1–120.

- Baldermann, S.; Kato, M.; Kurosawa, M.; Kurobayashi, Y.; Fujita, A.; Fleischmann, P.; Watanabe, N. Functional characterization of a carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase 1 and its relation to the carotenoid accumulation and volatile emission during the floral development of Osmanthus fragrans Lour. J. Exp. Bot. 2010, 61, 2967–2977.

- Dendy, D.A.V. The assay of annatto preparations by thin-layer chromatography. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1966, 17, 75–76.

- Scotter, M. The chemistry and analysis of annatto food colouring: A review. Food Addit. Contam. Part A 2009, 26, 1123–1145.

- Tibodeau, J.D.; Isham, C.R.; Bible, K.C. Annatto constituent cis-bixin has selective antimyeloma effects mediated by oxidative stress and associated with inhibition of thioredoxin and thioredoxin reductase. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2010, 13, 987–997.

- Yu, Y.; Wu, D.M.; Li, J.; Deng, S.H.; Liu, T.; Zhang, T.; He, M.; Zhao, Y.Y.; Xu, Y. Bixin Attenuates Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis by Suppressing TXNIP/NLRP3 Inflammasome Activity and Activating NRF2 Signaling. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 593368.

- de Oliveira Júnior, R.G.; Bonnet, A.; Braconnier, E.; Groult, H.; Prunier, G.; Beaugeard, L.; Grougnet, R.; da Silva Almeida, J.R.G.; Ferraz, C.A.A.; Picot, L. Bixin, an apocarotenoid isolated from Bixa orellana L., sensitizes human melanoma cells to dacarbazine-induced apoptosis through ROS-mediated cytotoxicity. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2019, 125, 549–561.

- Alavizadeh, S.H.; Hosseinzadeh, H. Bioactivity assessment and toxicity of crocin: A comprehensive review. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2014, 64, 65–80.

- Noorbala, A.A.; Akhondzadeh, S.; Tahmacebi-Pour, N.; Jamshidi, A.H. Hydro-alcoholic extract of Crocus sativus L. versus fluoxetine in the treatment of mild to moderate depression: A double-blind, randomized pilot trial. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005, 97, 281–284.

- Magesh, V.; DurgaBhavani, K.; Senthilnathan, P.; Rajendran, P.; Sakthisekaran, D. In vivo protective effect of crocetin on benzo(a)pyrene-induced lung cancer in Swiss albino mice. Phytother. Res. 2009, 23, 533–539.

- Aung, H.H.; Wang, C.Z.; Ni, M.; Fishbein, A.; Mehendale, S.R.; Xie, J.T.; Shoyama, C.Y.; Yuan, C.S. Crocin from Crocus sativus possesses significant anti-proliferation effects on human colorectal cancer cells. Exp. Oncol. 2007, 29, 175–180.

- Khavari, A.; Bolhassani, A.; Alizadeh, F.; Bathaie, S.Z.; Balaram, P.; Agi, E.; Vahabpour, R. Chemo-immunotherapy using saffron and its ingredients followed by E7-NT (gp96) DNA vaccine generates different anti-tumor effects against tumors expressing the E7 protein of human papillomavirus. Arch. Virol. 2015, 160, 499–508.

- Moshiri, M.; Vahabzadeh, M.; Hosseinzadeh, H. Clinical Applications of Saffron (Crocus sativus) and its Constituents: A Review. Drug Res. 2015, 65, 287–295.

- Milani, A.; Basirnejad, M.; Shahbazi, S.; Bolhassani, A. Carotenoids: Biochemistry, pharmacology and treatment. Br. J. Pharm. 2017, 174, 1290–1324.

- Pashirzad, M.; Shafiee, M.; Avan, A.; Ryzhikov, M.; Fiuji, H.; Bahreyni, A.; Khazaei, M.; Soleimanpour, S.; Hassanian, S.M. Therapeutic potency of crocin in the treatment of inflammatory diseases: Current status and perspective. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019.

- Sharma, V.; Singh, G.; Kaur, H.; Saxena, A.K.; Ishar, M.P.S. Synthesis of β-ionone derived chalcones as potent antimicrobial agents. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 22, 6343–6346.

- Suryawanshi, S.N.; Bhat, B.A.; Pandey, S.; Chandra, N.; Gupta, S. Chemotherapy of leishmaniasis. Part VII: Synthesis and bioevaluation of substituted terpenyl pyrimidines. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2007, 42, 1211–1217.

- Griffin, S.G.; Wyllie, S.G.; Markham, J.L.; Leach, D.N. The role of structure and molecular properties of terpenoids in determining their antimicrobial activity. Flavour Fragr. J. 1999, 14, 322–332.

- Wilson, D.M.; Gueldner, R.C.; Mckinney, J.K.; Lievsay, R.H.; Evans, B.D.; Hill, R.A. Effect of β-lonone onaspergillus flavus andaspergillus parasiticus growth, sporulation, morphology and aflatoxin production. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 1981, 58, A959–A961.

- Ansari, M.; Emami, S. β-Ionone and its analogs as promising anticancer agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 123, 141–154.

- Dong, H.-W.; Wang, K.; Chang, X.-X.; Jin, F.-F.; Wang, Q.; Jiang, X.-F.; Liu, J.-R.; Wu, Y.-H.; Yang, C. Beta-ionone-inhibited proliferation of breast cancer cells by inhibited COX-2 activity. Arch. Toxicol. 2019, 93, 2993–3003.

- Balbi, A.; Anzaldi, M.; Mazzei, M.; Miele, M.; Bertolotto, M.; Ottonello, L.; Dallegri, F. Synthesis and biological evaluation of novel heterocyclic ionone-like derivatives as anti-inflammatory agents. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2006, 14, 5152–5160.

- Xie, H.; Liu, T.; Chen, J.; Yang, Z.; Xu, S.; Fan, Y.; Zeng, J.; Chen, Y.; Ma, Z.; Gao, Y.; et al. Activation of PSGR with β-ionone suppresses prostate cancer progression by blocking androgen receptor nuclear translocation. Cancer Lett. 2019, 453, 193–205.

- Mo, H.; Elson, C.E. Apoptosis and Cell-Cycle Arrest in Human and Murine Tumor Cells Are Initiated by Isoprenoids. J. Nutr. 1999, 129, 804–813.

- Janakiram, N.B.; Cooma, I.; Mohammed, A.; Steele, V.E.; Rao, C.V. β-Ionone inhibits colonic aberrant crypt foci formation in rats, suppresses cell growth, and induces retinoid X receptor-α in human colon cancer cells. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2008, 7, 181–190.

- Dong, H.-W.; Zhang, S.; Sun, W.-G.; Liu, Q.; Ibla, J.C.; Soriano, S.G.; Han, X.-H.; Liu, L.-X.; Li, M.-S.; Liu, J.-R. β-Ionone arrests cell cycle of gastric carcinoma cancer cells by a MAPK pathway. Arch. Toxicol. 2013, 87, 1797–1808.

- Liu, J.-R.; Sun, X.-R.; Dong, H.-W.; Sun, C.-H.; Sun, W.-G.; Chen, B.-Q.; Song, Y.-Q.; Yang, B.-F. β-Ionone suppresses mammary carcinogenesis, proliferative activity and induces apoptosis in the mammary gland of the Sprague-Dawley rat. Int. J. Cancer 2008, 122, 2689–2698.

- Aloum, L.; Alefishat, E.; Adem, A.; Petroianu, G. Ionone Is More than a Violet’s Fragrance: A Review. Molecules 2020, 25, 5822.

- Luetragoon, T.; Pankla Sranujit, R.; Noysang, C.; Thongsri, Y.; Potup, P.; Suphrom, N.; Nuengchamnong, N.; Usuwanthim, K. Anti-Cancer Effect of 3-Hydroxy-β-Ionone Identified from Moringa oleifera Lam. Leaf on Human Squamous Cell Carcinoma 15 Cell Line. Molecules 2020, 25, 3563.

- Neuhaus, E.M.; Zhang, W.; Gelis, L.; Deng, Y.; Noldus, J.; Hatt, H. Activation of an Olfactory Receptor Inhibits Proliferation of Prostate Cancer Cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 16218–16225.

- Sanz, G.; Leray, I.; Dewaele, A.; Sobilo, J.; Lerondel, S.; Bouet, S.; Grébert, D.; Monnerie, R.; Pajot-Augy, E.; Mir, L.M. Promotion of Cancer Cell Invasiveness and Metastasis Emergence Caused by Olfactory Receptor Stimulation. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e85110.

- Hou, X.; Rivers, J.; León, P.; McQuinn, R.P.; Pogson, B.J. Synthesis and Function of Apocarotenoid Signals in Plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2016, 21, 792–803.

- Scannerini, S.; Bonfante-Fasolo, P. Unusual plasties in an endomycorrhizal root. Can. J. Bot. 1977, 55, 2471–2474.

- Maier, W.; Hammer, K.; Dammann, U.; Schulz, B.; Strack, D. Accumulation of sesquiterpenoid cyclohexenone derivatives induced by an arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus in members of the Poaceae. Planta 1997, 202, 36–42.

- Fiorilli, V.; Vannini, C.; Ortolani, F.; Garcia-Seco, D.; Chiapello, M.; Novero, M.; Domingo, G.; Terzi, V.; Morcia, C.; Bagnaresi, P.; et al. Omics approaches revealed how arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis enhances yield and resistance to leaf pathogen in wheat. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 9625.

- Zouari, I.; Salvioli, A.; Chialva, M.; Novero, M.; Miozzi, L.; Tenore, G.C.; Bagnaresi, P.; Bonfante, P. From root to fruit: RNA-Seq analysis shows that arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis may affect tomato fruit metabolism. BMC Genom. 2014, 15, 221.

- Ruiz-Lozano, J.M.; Porcel, R.; Azcón, C.; Aroca, R. Regulation by arbuscular mycorrhizae of the integrated physiological response to salinity in plants: New challenges in physiological and molecular studies. J. Exp. Bot. 2012, 63, 4033–4044.

- Maier, W.; Peipp, H.; Schmidt, J.; Wray, V.; Strack, D. Levels of a Terpenoid Glycoside (Blumenin) and Cell Wall-Bound Phenolics in Some Cereal Mycorrhizas. Plant Physiol. 1995, 109, 465–470.

- Maier, W.; Schmidt, J.; Nimtz, M.; Wray, V.; Strack, D. Secondary products in mycorrhizal roots of tobacco and tomato. Phytochemistry 2000, 54, 473–479.

- Fiorilli, V.; Wang, J.Y.; Bonfante, P.; Lanfranco, L.; Al-Babili, S. Apocarotenoids: Old and New Mediators of the Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Symbiosis. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1186.

- Fester, T.; Maier, W.; Strack, D. Accumulation of secondary compounds in barley and wheat roots in response to inoculation with an arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus and co-inoculation with rhizosphere bacteria. Mycorrhiza 1999, 8, 241–246.

- Wang, M.; Schäfer, M.; Li, D.; Halitschke, R.; Dong, C.; McGale, E.; Paetz, C.; Song, Y.; Li, S.; Dong, J.; et al. Blumenols as shoot markers of root symbiosis with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Elife 2018, 7, e37093.

- Mikhlin, E.D.; Radina, V.P.; Dmitrovskii, A.A.; Blinkova, L.P.; Butova, L.G. Antifungal and antimicrobic activity of β-ionone and vitamin A derivatives. Prikl. Biokhim. Mikrobiol. 1983, 19, 795–803. (In Russian)

- Utama, I.M.; Wills, R.B.; Ben-Yehoshua, S.; Kuek, C. In vitro efficacy of plant volatiles for inhibiting the growth of fruit and vegetable decay microorganisms. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 6371–6377.

- Schiltz, P. Action inhibitrice de la β-ionone au cours du développement de Peronospora tabacina. Ann. Tab. Sect. 2 1974, 11, 207–216.

- Salt, S.D.; Tuzun, S.; Kuć, J. Effects of β-ionone and abscisic acid on the growth of tobacco and resistance to blue mold. Mimicry of effects of stem infection by Peronospora tabacina Adam. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 1986, 28, 287–297.

- Cáceres, L.A.; Lakshminarayan, S.; Yeung, K.K.; McGarvey, B.D.; Hannoufa, A.; Sumarah, M.W.; Benitez, X.; Scott, I.M. Repellent and Attractive Effects of α-, β-, and Dihydro-β- Ionone to Generalist and Specialist Herbivores. J. Chem. Ecol. 2016, 42, 107–117.

- Gruber, M.Y.; Xu, N.; Grenkow, L.; Li, X.; Onyilagha, J.; Soroka, J.J.; Westcott, N.D.; Hegedus, D.D. Responses of the Crucifer Flea Beetle to Brassica Volatiles in an Olfactometer. Environ. Entomol. 2009, 38, 1467–1479.

- Faria, L.R.R.; Zanella, F.C.V. Beta-ionone attracts Euglossa mandibularis (Hymenoptera, Apidae) males in western Paraná forests. Rev. Bras. Entomol. 2015, 59, 260–264.

- Halloran, S.; Collignon, R.M.; Mcelfresh, J.S.; Millar, J.G. Fuscumol and Geranylacetone as Pheromone Components of Californian Longhorn Beetles (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) in the Subfamily Spondylidinae. Environ. Entomol. 2018, 47, 1300–1305.

- Keesey, I.W.; Knaden, M.; Hansson, B.S. Olfactory specialization in Drosophila suzukii supports an ecological shift in host preference from rotten to fresh fruit. J. Chem. Ecol. 2015, 41, 121–128.

- Bolton, L.G.; Piñero, J.C.; Barrett, B.A. Electrophysiological and Behavioral Responses of Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae) Towards the Leaf Volatile β-cyclocitral and Selected Fruit-Ripening Volatiles. Environ. Entomol. 2019, 48, 1049–1055.

- Murata, M.; Kobayashi, T.; Seo, S. α-Ionone, an Apocarotenoid, Induces Plant Resistance to Western Flower Thrips, Frankliniella occidentalis, Independently of Jasmonic Acid. Molecules 2019, 25, 17.

- Quiroz, A.; Pettersson, J.; Pickett, J.A.; Wadhams, L.J.; Niemeyer, H.M. Semiochemicals mediating spacing behaviour of bird cherry-oat aphid, Rhopalosiphum padi, feeding on cereals. J. Chem. Ecol. 1997, 23, 2599–2607.

- Du, Y.; Poppy, G.M.; Powell, W.; Pickett, J.A.; Wadhams, L.J.; Woodcock, C.M. Identification of Semiochemicals Released During Aphid Feeding That Attract Parasitoid Aphidius ervi. J. Chem. Ecol. 1998, 24, 1355–1368.

- Wei, S.; Hannoufa, A.; Soroka, J.; Xu, N.; Li, X.; Zebarjadi, A.; Gruber, M. Enhanced β-ionone emission in Arabidopsis over-expressing AtCCD1 reduces feeding damage in vivo by the crucifer flea beetle. Environ. Entomol. 2011, 40, 1622–1630.

- Dickinson, A.J.; Lehner, K.; Mi, J.; Jia, K.-P.; Mijar, M.; Dinneny, J.; Al-Babili, S.; Benfey, P.N. β-Cyclocitral is a conserved root growth regulator. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 10563–10567.

- D’Alessandro, S.; Ksas, B.; Havaux, M. Decoding β-Cyclocitral-Mediated Retrograde Signaling Reveals the Role of a Detoxification Response in Plant Tolerance to Photooxidative Stress. Plant Cell 2018, 30, 2495–2511.

- Ramel, F.; Birtic, S.; Ginies, C.; Soubigou-Taconnat, L.; Triantaphylidès, C.; Havaux, M. Carotenoid oxidation products are stress signals that mediate gene responses to singlet oxygen in plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 5535–5540.

- Shumbe, L.; D’Alessandro, S.; Shao, N.; Chevalier, A.; Ksas, B.; Bock, R.; Havaux, M. METHYLENE BLUE SENSITIVITY 1 (MBS1) is required for acclimation of Arabidopsis to singlet oxygen and acts downstream of β-cyclocitral. Plant Cell Environ. 2017, 40, 216–226.

- Campbell, R.; Ducreux, L.J.M.; Morris, W.L.; Morris, J.A.; Suttle, J.C.; Ramsay, G.; Bryan, G.J.; Hedley, P.E.; Taylor, M.A. The metabolic and developmental roles of carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase4 from potato. Plant Physiol. 2010, 154, 656–664.

- D’Alessandro, S.; Havaux, M. Sensing β-carotene oxidation in photosystem II to master plant stress tolerance. New Phytol. 2019, 223, 1776–1783.

- Kato-Noguchi, H. An endogenous growth inhibitor, 3-hydroxy-β-ionone. I. Its role in light-induced growth inhibition of hypocotyls of Phaseolus vulgaris. Physiol. Plant. 1992, 86, 583–586.

- Kato-noguchi, H.; Kosemura, S.; Yamamura, S.; Hasegawa, K. A growth inhibitor, R-(−)-3-hydroxy-β-ionone, from lightgrown shoots of a dwarf cultivar of Phaseolus vulgaris. Phytochemistry 1993, 33, 553–555.

- Kato-Noguchi, H.; Seki, T. Allelopathy of the moss Rhynchostegium pallidifolium and 3-hydroxy-β-ionone. Plant Signal. Behav. 2010, 5, 702–704.