| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Arsalan Ul Haq | + 3031 word(s) | 3031 | 2021-08-17 12:08:42 | | | |

| 2 | Lindsay Dong | Meta information modification | 3031 | 2021-09-28 04:32:36 | | |

Video Upload Options

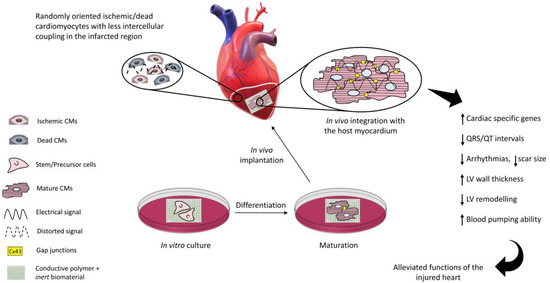

The function of the heart pump may be impaired by events such as myocardial infarction, the consequence of coronary artery thrombosis due to blood clots or plaques. A whole heart transplant remains the gold standard so far and the current pharmacological approaches tend to stop further myocardium deterioration, but this is not a long-term solution. Electrically conductive, scaffold-based cardiac tissue engineering provides a promising solution to repair the injured myocardium. The non-conductive component of the scaffold provides a biocompatible microenvironment to the cultured cells while the conductive component improves intercellular coupling as well as electrical signal propagation through the scar tissue when implanted at the infarcted site. The in vivo electrical coupling of the cells leads to a better regeneration of the infarcted myocardium, reducing arrhythmias, QRS/QT intervals, and scar size and promoting cardiac cell maturation.

1. Introduction

Myocardial infarction (MI) is one of the clusters of numerous other cardiovascular diseases and occurs due to the blockage of the coronary artery delivering blood (ischemia) to the ventricle with consequent oxygen shortage to the contractile cells (cardiomyocytes) [1]. The final result is that, after MI, billions of cardiomyocytes (CMs) with limited proliferation capacity are lost and substituted by heterogeneous collagen-rich fibrotic scar tissue [2][3]. Among others, the fibrotic scar does not display contractile capabilities and does not appropriately conduct electric currents, thus generating myocardial arrhythmias and asynchronous beating, contributing to determine heart failure in the worst-case scenario [2]. The current pharmacological approaches are palliative [4] and finalized to prevent intra-coronary blood clotting (thrombolytics, antiplatelet agents, such as aspirin, etc.) and post-ischemic ventricular dilation (ACE-inhibitors, β-blockers, etc.), but do not induce regeneration of the injured cardiac tissue. So far, the heart transplant is the gold standard in post-MI end-stage heart failure, but the lack of organ donors and the possibility of immune rejection makes this approach elusive [5].

In recent years, the parallel progresses in cell biology, materials science, and advanced nano-manufacturing procedures have allowed us to envision the possibility to set up novel strategies (collectively dubbed “tissue engineering”) to combine cells and biomaterials to fabricate myocardium-like structures in vitro to be engrafted into the heart to repair the damaged parts. This approach is characterized by an extreme level of complexity and, as a matter of fact, after more than two decades of extensive efforts, many issues remain to be answered before tissue engineering products can be used at the bedside.

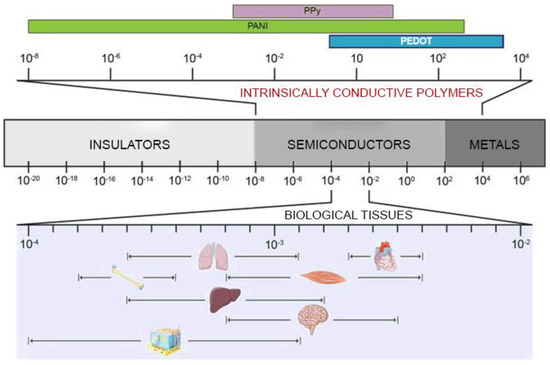

Natural or synthetic biomaterials, such as cardiac patches [6], injectable hydrogels [7], nanofiber composites [8], nanoparticles [9], and 3D hydrogel constructs [10], have been scrutinized to produce structures that mimic the mechanical properties of the extracellular matrix of the myocardium and potentially restoring the cardiac functions [11][12]. However, the issues related to arrhythmias and asynchronous beating of the injured myocardium are not resolved due to the non-conductive nature of most of the polymers used so far. The solution to this issue has been envisioned in conveying electric signals through scaffolds with embedded polymers displaying electroconductive characteristics comparable to the biological tissues (Figure 1) and this has already been demonstrated to enhance cell differentiation to mature CMs [13].

Electrically inert biomaterials can be blended with conductive polymers, such as polyaniline (PANI), polypyrrole (PPy), and Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiphene)/PEDOT, which belong to the family of intrinsically conductive organic materials [14]. The resulting electroconductive scaffold would harness the biocompatibility and the mechanical properties of the inert biomaterial and the electrical nature of the conductive component to drive the differentiation of the cultured stem/progenitor cells to cardiomyocyte-like cells with synchronous beating patterns, and enhance the expression of cardiac-specific genes.

2. Conductive Polymer-Based Scaffolds in Cardiac Tissue Engineering

2.1. Polyaniline

| Conductive Substrate |

Mechanical Properties |

Electrical Properties |

Cell Line or Tissue |

Biological Response |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poly-l-Lysine-PANI nanotubes membranes [26] |

Rat CMs | Better CMs proliferation | ||

| PLCL, PANI electrospun membranes [27] |

E = 50 MPa, εr = 207.85%, UTS = 0.69 MPa |

Four-probe technique, σ = 13.8 mS/cm |

Human fibroblasts, NIH-3T3, C2C12 |

Improved cell adhesion and metabolic activity |

| PGLD, PANI nanotubes membranes [28] |

Cho cells, neonatal rat CMs |

Good biocompatibility | ||

| PU-AP/PCL porous scaffold [29] |

Ec = 4.1 MPa, C.S = 1.3 MPa |

Four-probe technique, σ = 10−5 S/cm |

Neonatal rat CMs | Enhanced Actn4, Cx43, and cTnT2 expressions. |

| PANI/PCL patch [30] |

Two-probe technique, σ = 80 µS/cm |

hMSCs | Differentiation of hMSCs to CM-like cells |

|

| PDLA/PANI electrospun membranes [31] |

σ = 44 mS/cm | primary rat muscle cells | Improved cell adhesion and proliferation |

|

| Gelatin/PANI electrospun membranes [32] |

E = 1384 MPa, UTS = 10.49 MPa, εr = 9% |

Four-probe technique, σ = 17 mS/cm |

H9c2 | Smooth muscle-like morphology rich in microfilaments |

| Gelatin/PANI hydrogels [33] |

G’ = 5 Pa, G” = 26 Pa |

Pocket conductivity meter, σ = 0.45 mS/cm |

C2C12, BM-MSCs |

Improved cell-cell signalling and proliferation |

| PU-AP/PCL films [34] |

E’ = 10 MPa at 37 °C |

Four-probe technique, σ = 10−5 S/cm |

L929, HUVECs |

Improved cytocompatibility, good antioxidant properties |

| PLGA, PANI electrospun meshes [35] |

E = 91.7 MPa | Four-point probe, σ = 3.1 mS/cm |

Neonatal rat CMs | Enhanced Cx43 and cTnI expressions |

| PGS/PANI composites [36] |

E = 6 MPa, UTS = 9.2 MPa, εr = 40% |

Four-probe technique, σ = 18 mS/cm |

C2C12 | Good cell retention, growth, and proliferation |

| PCL, amino capped AT films [37] | E = 31.2 MPa, UTS = 48.3 MPa, εr = 646% |

- | C2C12 | Spindle like morphology, myotube formation |

| PCL, PANI electrospun membranes [38] |

E = 55.2 MPa, UTS = 10.5 MPa, εr = 38.0% |

Four-point probe, σ = 63.6 mS/cm |

C2C12 | Myotube formation |

| PANI, E-PANI films [39] |

Z > 10 MΩ/sqr for PANI Z = 6 MΩ/sqr for E-PANI |

H9c2 | Improved proliferation and cell attachment on E-PANI |

|

| PLA/PANI electrospun membranes [40] | Four-probe technique, σ = 21 µS/m |

H9c2, rat CMs |

Myotube formation from H9c2 cells, enhanced Cx43 and α-actinin expression, improved Ca2+ transients for CMs |

|

| PCL/SF/PANI hydrogels [41] |

εr = 107% | C2C12 | Excellent cell alignment, myotube formation |

|

| Chitosan-AT/PEG-DA hydrogels [42] | G’ = 7 kPa | Pocket conductivity meter, σ = 2.42 mS/cm |

C2C12, H9c2 |

Improved cell viability |

| PGS-AT elastomers [43] |

E = 2.2 MPa, UTS = 2.0 MPa, εr = 141% |

- | H9c2, rat CMs |

Synchronous CM beating with improved Ca2+ transients, H9c2 showed good orientation, enhanced Cx43 and α-actinin expression |

| PANI, Collagen, HA electrospun mats [44] |

E = 0.02 MPa, UTS= 4 MPa, εr = 78% |

Four-probe technique, σ = 2 mS/cm |

Neonatal rat CMs, hiPSCs | Synchronous beating of CMs derived from hiPSCs. Enhanced Cx43 and cTnI expression |

| AP, PLA films [45] |

Four-point probe, σ = 10−6 to 10−5 S/cm |

H9c2 | Pseudopodia like morphology, improved Ca2+ transients |

|

| Chitosan, PANI patch [46] |

E = 6.73 MPa, UTS = 5.26 MPa, εr = 79% |

Four-probe technique, σ = 0.162 S/cm |

Rat MI heart |

Improved CV in the infarcted region with healing effects |

| PA, PANI patch [47] |

Elongation = 84% | Digital Avometer, σ = 2.79 S/m |

Pork heart | Cardiac ECM mimicking |

| HPLA/AT films [48] |

εr = 42.7%, E = 758 MPa |

C2C12 | Myotube formation | |

| Dextran-AT/chitosan [49] | G’ = 620 Pa at t = 50 min |

Four-probe technique, σ = 0.03 mS/cm |

L929, C2C12 |

high proliferation rate, good in vivo degradation, generation of new myofibers |

2.2. Polypyrrole

| Conductive Substrate |

Mechanical Properties |

Electrical Properties |

Cell Line or Tissue |

Biological Response |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCL, PPy films [62] |

Nanoindentation test, E = 0.93 GPa | Keithley Parameter Analyzer, ρ = 1.0 kΩ-cm |

HL-1 murine CMs | Enhanced Cx43 expression, improved Ca2+ transients |

| Chitosan, PPy porous membranes [63] | E = 486.7 kPa | Three-probe detector, σ = 63 mS/m |

NRVMs, rat MI model |

Improved cytoskeletal organisation with high beating amplitude, tissue morphogenesis at the MI site |

| SF, PPy composites [59] |

E = 200 MPa, UTS = 7 MPa |

Four-probe technique, σ = 1 S/cm |

hPSC-CMs | Enhanced expression of Cx43, Myh7, cTnT2, SCN5A genes, elongated Z-band width and sarcomeric length |

| Chitosan, PPy hydrogels [58] |

E = 3 kPa | Four-point probe, σ = 0.23 mS/cm |

Neonatal rat CMs, rat SMCs |

Good proliferation with elevated calcium transients and shorter QRS intervals |

| PLGA, PPy membranes [57] |

Mice CPCs, hiPSCs |

Good biocompatibility and proliferation rate |

||

| PLGA, PPy membranes [61] |

hiPSCs | Differentiation of hiPSCs to CMs, enhanced expression of actinin, Nkx2.5, GATA4, and Oct4 | ||

| PCL, gelatin, PPy electrospun membranes [64] |

E = 50.3 MPa, εr = 3.7% |

Four-probe technique, σ = 0.37 mS/cm |

Rabbit primary CMs | High proliferation rate, enhanced expression of Cx43, cTnT, and α-actinin |

| PPy, HPAE hydrogels [65] |

G’ = 35 kPa, | Four-probe technique, σ = 0.65 mS/cm |

L929, BMSCs |

Enhanced Cx43, α-SMA expressions, excellent cell viability and biocompatibility |

2.3. Poly(3,4-Ethylenedioxythiophene)/PEDOT

| Conductive Substrate |

Mechanical Properties | Electrical Properties |

Cell Line | Biological Response |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEG/PEDOT:PSS hydrogels [69] |

Ec = 21 kPa | Four-probe technique, σ = 16.9 mS/cm |

H9c2 | Good cell viability and proliferation |

| GelMA/PEDOT:PSS hydrogels [71] | E = 10.3 kPa | ElS, Z = 261 kΩ at 1 Hz |

C2C12 | Good cell viability and proliferation but high polymer concentration was detrimental to cells |

| Collagen/alginate/ PEDOT:PSS hydrogels [72] |

G = 220 Pa, τmax = 41 Pa |

Four-probe technique, σ = 3.5 mS/cm |

CMs, hiPSCs-CMs |

Good cell viability, proliferation, and adhesion, synchronous beating patterns |

| Alginate/PEDOT hydrogels [73] |

Ec = 175 kPa, G’ = 100 kPa, G” = 10 kPa |

Electrochemical workstation, σ = 61 mS/cm |

BADSCs | Differentiation of BADSCs to CMs with enhanced expression of cTnT, α-actinin, Cx43 |

| NBR/PEGDM/PEDOT electrospun membranes [70] |

E = 3.8 MPa, εr = 75.1% |

Four-probe technique, σ = 5.8 S/cm |

Cardiac fibroblasts |

Well organised sarcomeres, enhanced expression of α-actinin, Cx43 |

| PCL/PEDOT:PSS microfibrous scaffold [74] |

E = 13 MPa | H9c2, primary CMs |

Enhanced expression of Cx43 and α-actinin, synchronous beating patterns of CMs |

3. The Underlying Mechanisms of the Positive Role of Conductive Substrates in Cardiac Tissue Engineering

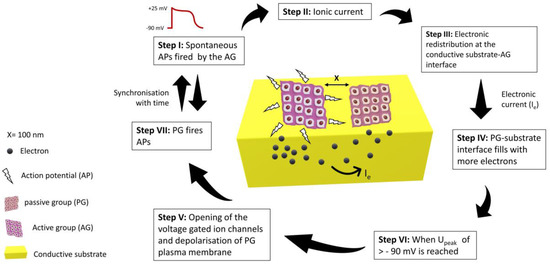

Though the electroconductive scaffolds provide better platforms for the tissue engineering of nerve, cardiac, and skeletal muscle tissues, the mechanism by which these constructs influence cellular behaviour is yet to be known [75]. To uncover this, an equivalent circuit model was proposed for two groups of cardiomyocytes seeded on a conductive substrate. One group was assumed to be active (AG), which could fire spontaneous action potentials, while the other was assumed to be passive (PG), which could not fire spontaneous action potentials, but it was well electrically coupled. AG was considered the only source of ionic current, and the passive group was only affected by the electrical currents from the neighbouring AG. Nano gaps/clefts are formed between the cell membrane of the cultured cardiomyocytes and the substrate surface. Ionic solution filled these clefts during culturing, and it was modelled as seal resistance [76]. Seal resistance is usually generated by the solution between cell-substrate interfacial gaps and has a direct link with the adhesion strength of cells with the substrate [77]. When cells in the active group (AG) fire spontaneous action potentials, the electronic redistribution on the surface of the conductive substrate takes place just beneath the cells. The interfacial clefts between PG cells and substrate fill with more anions due to this electronic redistribution, which depolarises the plasma membrane of cells and could trigger an action potential. Larger seal resistance gives rise to higher excitation potential (Upeak) which indicates a strong electrical coupling between AG and PG. The passive group will fire an action potential once the threshold (Upeak) crosses the resting membrane potential of −90 mV [78][79]. In this way, PG could be stimulated and electrically synchronised to AG under the influence of action potentials generated by the active group, as shown in Figure 3.

4. Conductive Substrates for In Vivo Cardiac Repair

Electroconductive scaffolds represent a leap forward in the effort to manufacture supports to properly address cell fate towards a cardiomyocytic phenotype. The scaffold fabrication is a complex endeavour finalised to replicate in vitro the ECM microenvironment to foster proper cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions driving the cardiomyocyte maturation process. An optimal scaffold must be biocompatible (but not necessarily biodegradable, if the constituent materials are immunopermissive), with (i) adequate porosity (to deliver biologically active factors and remove cell waste) and (ii) mechano-structural design (to deliver physical signals, such as stiffness, micro/nano-topography, etc.), and (iii) with electroconductivity appropriate to mimic the ECM structure and function. Finally, these characteristics must allow the integration of the engineered tissue with the native injured myocardium to restore heart function.

5. Future Research

A biodegradable, intrinsically conductive polymer whose conductivity could be tuned to mimic the electrical features of the myocardium is of great necessity in cardiac tissue engineering. No material has ever been produced which would undergo perpetual contraction and relaxation cycles for an entire span of natural life, like myocardium. To mimic this versatility, future studies should take into consideration the complex biomechanics, anisotropy, micro/nano-architecture, and electrical properties of the myocardium.

References

- Nabel, E.G.; Braunwald, E. A Tale of Coronary Artery Disease and Myocardial Infarction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 54–63.

- Frangogiannis, N.G. Pathophysiology of myocardial infarction. Compr. Physiol. 2015, 5, 1841–1875.

- Bergmann, O.; Zdunek, S.; Felker, A.; Salehpour, M.; Alkass, K.; Bernard, S.; Sjostrom, S.L.; Szewczykowska, M.; Jackowska, T.; Dos Remedios, C.; et al. Dynamics of Cell Generation and Turnover in the Human Heart. Cell 2015, 161, 1566–1575.

- Sadahiro, T. Cardiac regeneration with pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes and direct cardiac reprogramming. Regen. Ther. 2019, 11, 95–100.

- Zammaretti, P.; Jaconi, M. Cardiac tissue engineering: Regeneration of the wounded heart. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2004, 15, 430–434.

- Zhang, D.; Shadrin, I.Y.; Lam, J.; Xian, H.Q.; Snodgrass, H.R.; Bursac, N. Tissue-engineered cardiac patch for advanced functional maturation of human ESC-derived cardiomyocytes. Biomaterials 2013, 34, 5813–5820.

- Hasan, A.; Khattab, A.; Islam, M.A.; Hweij, K.A.; Zeitouny, J.; Waters, R.; Sayegh, M.; Hossain, M.M.; Paul, A. Injectable Hydrogels for Cardiac Tissue Repair after Myocardial Infarction. Adv. Sci. 2015, 2, 1500122.

- Kim, P.H.; Cho, J.Y. Myocardial tissue engineering using electrospun nanofiber composites. BMB Rep. 2016, 49, 26–36.

- Hasan, A.; Morshed, M.; Memic, A.; Hassan, S.; Webster, T.J.; Marei, H.E.S. Nanoparticles in tissue engineering: Applications, challenges and prospects. Int. J. Nanomed. 2018, 13, 5637–5655.

- Ciocci, M.; Mochi, F.; Carotenuto, F.; Di Giovanni, E.; Prosposito, P.; Francini, R.; De Matteis, F.; Reshetov, I.; Casalboni, M.; Melino, S.; et al. Scaffold-in-scaffold potential to induce growth and differentiation of cardiac progenitor cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2017, 26, 1438–1447.

- Carotenuto, F.; Teodori, L.; Maccari, A.M.; Delbono, L.; Orlando, G.; Di Nardo, P. Turning regenerative technologies into treatment to repair myocardial injuries. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2020, 24, 2704–2716.

- Carotenuto, F.; Manzari, V.; Di Nardo, P. Cardiac Regeneration: The Heart of the Issue. Curr. Transpl. Rep. 2021, 8, 67–75.

- Solazzo, M.; O’Brien, F.J.; Nicolosi, V.; Monaghan, M.G. The rationale and emergence of electroconductive biomaterial scaffolds in cardiac tissue engineering. APL Bioeng. 2019, 3, 041501.

- Quijada, C. Special issue: Conductive polymers: Materials and applications. Materials 2020, 13, 2344.

- Wei, B.; Jin, J.P. TNNT1, TNNT2, and TNNT3: Isoform genes, regulation, and structure-function relationships. Gene 2016, 582, 1–13.

- Watt, A.J.; Battle, M.A.; Li, J.; Duncan, S.A. GATA4 is essential for formation of the proepicardium and regulates cardiogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 12573–12578.

- Saadane, N.; Alpert, L.; Chalifour, L.E. Expression of immediate early genes, GATA-4, and Nkx-2.5 in adrenergic-induced cardiac hypertrophy and during regression in adult mice. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1999, 127, 1165–1176.

- Kotini, M.; Barriga, E.H.; Leslie, J.; Gentzel, M.; Rauschenberger, V.; Schambon, A.; Mayor, R. Gap junction protein Connexin-43 is a direct transcriptional regulator of N-cadherin in vivo. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3846.

- He, S.; Wu, J.; Li, S.-H.; Wang, L.; Sun, Y.; Xie, J.; Ramnath, D.; Weisel, R.D.; Yau, T.M.; Sung, H.-W.; et al. The conductive function of biopolymer corrects myocardial scar conduction blockage and resynchronizes contraction to prevent heart failure. Biomaterials 2020, 258, 120285.

- Lalegül-ülker, Ö.; Murat, Y. Magnetic and electrically conductive silica-coated iron oxide/polyaniline nanocomposites for biomedical applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2021, 119, 111600.

- Wibowo, A.; Vyas, C.; Cooper, G.; Qulub, F.; Suratman, R. 3D Printing of Polycaprolactone–Polyaniline Electroactive Sca ff olds for Bone Tissue Engineering. Materials 2020, 13, 512.

- Zhang, M.; Guo, B. Electroactive 3D Scaffolds Based on Silk Fibroin and Water-Borne Polyaniline for Skeletal Muscle Tissue Engineering. Macromol. Biosci. 2017, 17, 1–10.

- Karimi-soflou, R.; Nejati, S.; Karkhaneh, A. Electroactive and antioxidant injectable in-situ forming hydrogels with tunable properties by polyethylenimine and polyaniline for nerve tissue engineering. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2021, 199, 111565.

- Choi, C.H.; Park, S.H.; Woo, S.I. Binary and ternary doping of nitrogen, boron, and phosphorus into carbon for enhancing electrochemical oxygen reduction activity. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 7084–7091.

- Bhadra, J.; Alkareem, A.; Al-Thani, N. A review of advances in the preparation and application of polyaniline based thermoset blends and composites. J. Polym. Res. 2020, 27, 122.

- Fernandes, E.G.R.; Zucolotto, V.; De Queiroz, A.A.A. Electrospinning of hyperbranched poly-L-lysine/polyaniline nanofibers for application in cardiac tissue engineering. J. Macromol. Sci. Part A Pure Appl. Chem. 2010, 47, 1203–1207.

- Jeong, S.I.; Jun, I.D.; Choi, M.J.; Nho, Y.C.; Lee, Y.M.; Shin, H. Development of electroactive and elastic nanofibers that contain polyaniline and poly(L-lactide-co-ε-caprolactone) for the control of cell adhesion. Macromol. Biosci. 2008, 8, 627–637.

- Moura, R.M.; de Queiroz, A.A.A. Dendronized polyaniline nanotubes for cardiac tissue engineering. Artif. Organs 2011, 35, 471–477.

- Baheiraei, N.; Yeganeh, H.; Ai, J.; Gharibi, R.; Ebrahimi-Barough, S.; Azami, M.; Vahdat, S.; Baharvand, H. Preparation of a porous conductive scaffold from aniline pentamer-modified polyurethane/PCL blend for cardiac tissue engineering. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 2015, 103, 3179–3187.

- Borriello, A.; Guarino, V.; Schiavo, L.; Alvarez-Perez, M.A.; Ambrosio, L. Optimizing PANi doped electroactive substrates as patches for the regeneration of cardiac muscle. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2011, 22, 1053–1062.

- McKeon, K.D.; Lewis, A.; Freeman, J.W. Electrospun poly(D,L-lactide) and polyaniline scaffold characterization. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2010, 115, 1566–1572.

- Li, M.; Guo, Y.; Wei, Y.; MacDiarmid, A.G.; Lelkes, P.I. Electrospinning polyaniline-contained gelatin nanofibers for tissue engineering applications. Biomaterials 2006, 27, 2705–2715.

- Li, L.; Ge, J.; Guo, B.; Ma, P.X. In situ forming biodegradable electroactive hydrogels. Polym. Chem. 2014, 5, 2880–2890.

- Baheiraei, N.; Yeganeh, H.; Ai, J.; Gharibi, R.; Azami, M.; Faghihi, F. Synthesis, characterization and antioxidant activity of a novel electroactive and biodegradable polyurethane for cardiac tissue engineering application. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2014, 44, 24–37.

- Hsiao, C.W.; Bai, M.Y.; Chang, Y.; Chung, M.F.; Lee, T.Y.; Wu, C.T.; Maiti, B.; Liao, Z.X.; Li, R.K.; Sung, H.W. Electrical coupling of isolated cardiomyocyte clusters grown on aligned conductive nanofibrous meshes for their synchronized beating. Biomaterials 2013, 34, 1063–1072.

- Qazi, T.H.; Rai, R.; Dippold, D.; Roether, J.E.; Schubert, D.W.; Rosellini, E.; Barbani, N.; Boccaccini, A.R. Development and characterization of novel electrically conductive PANI-PGS composites for cardiac tissue engineering applications. Acta Biomater. 2014, 10, 2434–2445.

- Deng, Z.; Guo, Y.; Zhao, X.; Li, L.; Dong, R.; Guo, B.; Ma, P.X. Stretchable degradable and electroactive shape memory copolymers with tunable recovery temperature enhance myogenic differentiation. Acta Biomater. 2016, 46, 234–244.

- Chen, M.C.; Sun, Y.C.; Chen, Y.H. Electrically conductive nanofibers with highly oriented structures and their potential application in skeletal muscle tissue engineering. Acta Biomater. 2013, 9, 5562–5572.

- Bidez, P.R.; Li, S.; Macdiarmid, A.G.; Venancio, E.C.; Wei, Y.; Lelkes, P.I. Polyaniline, an electroactive polymer, supports adhesion and proliferation of cardiac myoblasts. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2006, 17, 199–212.

- Wang, L.; Wu, Y.; Hu, T.; Guo, B.; Ma, P.X. Electrospun conductive nanofibrous scaffolds for engineering cardiac tissue and 3D bioactuators. Acta Biomater. 2017, 59, 68–81.

- Wang, L.; Wu, Y.; Guo, B.; Ma, P.X. Nanofiber Yarn/Hydrogel Core-Shell Scaffolds Mimicking Native Skeletal Muscle Tissue for Guiding 3D Myoblast Alignment, Elongation, and Differentiation. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 9167–9179.

- Dong, R.; Zhao, X.; Guo, B.; Ma, P.X. Self-Healing Conductive Injectable Hydrogels with Antibacterial Activity as Cell Delivery Carrier for Cardiac Cell Therapy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 17138–17150.

- Hu, T.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, X.; Wang, L.; Bi, L.; Ma, P.X.; Guo, B. Micropatterned, electroactive, and biodegradable poly(glycerol sebacate)-aniline trimer elastomer for cardiac tissue engineering. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 366, 208–222.

- Roshanbinfar, K.; Vogt, L.; Ruther, F.; Roether, J.A.; Boccaccini, A.R.; Engel, F.B. Nanofibrous Composite with Tailorable Electrical and Mechanical Properties for Cardiac Tissue Engineering. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 8612.

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Huang, L.; Ito, Y.; Wang, Z.; Shi, X.; Wei, Y.; Jing, X.; Zhang, P. Intracellular calcium ions and morphological changes of cardiac myoblasts response to an intelligent biodegradable conducting copolymer. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2018, 90, 168–179.

- Mawad, D.; Mansfield, C.; Lauto, A.; Perbellini, F.; Nelson, G.W.; Tonkin, J.; Bello, S.O.; Carrad, D.J.; Micolich, A.P.; Mahat, M.M.; et al. A Conducting polymer with enhanced electronic stability applied in cardiac models. Sci. Adv. 2016, 2, e1601007.

- Yin, Y.; Mo, J.; Feng, J. Conductive fabric patch with controllable porous structure and elastic properties for tissue engineering applications. J. Mater. Sci. 2020, 55, 17120–17133.

- Xie, M.; Wang, L.; Guo, B.; Wang, Z.; Chen, Y.E.; Ma, P.X. Ductile electroactive biodegradable hyperbranched polylactide copolymers enhancing myoblast differentiation. Biomaterials 2015, 71, 158–167.

- Guo, B.; Qu, J.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, M. Degradable conductive self-healing hydrogels based on dextran-graft-tetraaniline and N-carboxyethyl chitosan as injectable carriers for myoblast cell therapy and muscle regeneration. Acta Biomater. 2019, 84, 180–193.

- Aznar-Cervantes, S.; Roca, M.I.; Martinez, J.G.; Meseguer-Olmo, L.; Cenis, J.L.; Moraleda, J.M.; Otero, T.F. Fabrication of conductive electrospun silk fibroin scaffolds by coating with polypyrrole for biomedical applications. Bioelectrochemistry 2012, 85, 36–43.

- Zanjanizadeh Ezazi, N.; Shahbazi, M.A.; Shatalin, Y.V.; Nadal, E.; Mäkilä, E.; Salonen, J.; Kemell, M.; Correia, A.; Hirvonen, J.; Santos, H.A. Conductive vancomycin-loaded mesoporous silica polypyrrole-based scaffolds for bone regeneration. Int. J. Pharm. 2018, 536, 241–250.

- Broda, C.R.; Lee, J.Y.; Sirivisoot, S.; Schmidt, C.E.; Harrison, B.S. A chemically polymerized electrically conducting composite of polypyrrole nanoparticles and polyurethane for tissue engineering. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 2011, 98, 509–516.

- Pan, X.; Sun, B.; Mo, X. Electrospun polypyrrole-coated polycaprolactone nanoyarn nerve guidance conduits for nerve tissue engineering. Front. Mater. Sci. 2018, 12, 438–446.

- Zhou, J.F.; Wang, Y.G.; Cheng, L.; Wu, Z.; Sun, X.D.; Peng, J. Preparation of polypyrrole-embedded electrospun poly(lactic acid) nanofibrous scaffolds for nerve tissue engineering. Neural Regen. Res. 2016, 11, 1644–1652.

- Björninen, M.; Gilmore, K.; Pelto, J.; Seppänen-Kaijansinkko, R.; Kellomäki, M.; Miettinen, S.; Wallace, G.; Grijpma, D.; Haimi, S. Electrically Stimulated Adipose Stem Cells on Polypyrrole-Coated Scaffolds for Smooth Muscle Tissue Engineering. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2017, 45, 1015–1026.

- Humpolíček, P.; Kašpárková, V.; Pacherník, J.; Stejskal, J.; Bober, P.; Capáková, Z.; Radaszkiewicz, K.A.; Junkar, I.; Lehocký, M. The biocompatibility of polyaniline and polypyrrole: A comparative study of their cytotoxicity, embryotoxicity and impurity profile. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2018, 91, 303–310.

- Gelmi, A.; Zhang, J.; Cieslar-Pobuda, A.; Ljunngren, M.K.; Los, M.J.; Rafat, M.; Jager, E.W.H. Electroactive 3D materials for cardiac tissue engineering. In Electroactive Polymer Actuators and Devices (EAPAD) 2015; SPIE-International Society for Optics and Photonics: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2015; Volume 9430.

- Mihic, A.; Cui, Z.; Wu, J.; Vlacic, G.; Miyagi, Y.; Li, S.H.; Lu, S.; Sung, H.W.; Weisel, R.D.; Li, R.K. A conductive polymer hydrogel supports cell electrical signaling and improves cardiac function after implantation into myocardial infarct. Circulation 2015, 132, 772–784.

- Tsui, J.H.; Ostrovsky-Snider, N.A.; Yama, D.M.P.; Donohue, J.D.; Choi, J.S.; Chavanachat, R.; Larson, J.D.; Murphy, A.R.; Kim, D.H. Conductive silk-polypyrrole composite scaffolds with bioinspired nanotopographic cues for cardiac tissue engineering. J. Mater. Chem. B 2018, 6, 7185–7196.

- Bird, S.D.; Doevendans, P.A.; Van Rooijen, M.A.; Brutel De La Riviere, A.; Hassink, R.J.; Passier, R.; Mummery, C.L. The human adult cardiomyocyte phenotype. Cardiovasc. Res. 2003, 58, 423–434.

- Gelmi, A.; Cieslar-Pobuda, A.; de Muinck, E.; Los, M.; Rafat, M.; Jager, E.W.H. Direct Mechanical Stimulation of Stem Cells: A Beating Electromechanically Active Scaffold for Cardiac Tissue Engineering. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2016, 5, 1471–1480.

- Spearman, B.S.; Hodge, A.J.; Porter, J.L.; Hardy, J.G.; Davis, Z.D.; Xu, T.; Zhang, X.; Schmidt, C.E.; Hamilton, M.C.; Lipke, E.A. Conductive interpenetrating networks of polypyrrole and polycaprolactone encourage electrophysiological development of cardiac cells. Acta Biomater. 2015, 28, 109–120.

- Song, X.; Mei, J.; Ye, G.; Wang, L.; Ananth, A.; Yu, L.; Qiu, X. In situ pPy-modification of chitosan porous membrane from mussel shell as a cardiac patch to repair myocardial infarction. Appl. Mater. Today 2019, 15, 87–99.

- Kai, D.; Prabhakaran, M.P.; Jin, G.; Ramakrishna, S. Polypyrrole-contained electrospun conductive nanofibrous membranes for cardiac tissue engineering. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 2011, 99, 376–385.

- Liang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.; Xu, Z.; Chen, J.; Bao, R.; Tan, B.; Cui, Y.; Fan, G.; Wang, W.; et al. Paintable and Rapidly Bondable Conductive Hydrogels as Therapeutic Cardiac Patches. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, e1704235.

- Lu, B.; Yuk, H.; Lin, S.; Jian, N.; Qu, K.; Xu, J.; Zhao, X. Pure PEDOT:PSS hydrogels. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1043.

- Guex, A.G.; Puetzer, J.L.; Armgarth, A.; Littmann, E.; Stavrinidou, E.; Giannelis, E.P.; Malliaras, G.G.; Stevens, M.M. Highly porous scaffolds of PEDOT:PSS for bone tissue engineering. Acta Biomater. 2017, 62, 91–101.

- Heo, D.N.; Lee, S.J.; Timsina, R.; Qiu, X.; Castro, N.J.; Zhang, L.G. Development of 3D printable conductive hydrogel with crystallized PEDOT:PSS for neural tissue engineering. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2019, 99, 582–590.

- Kim, Y.S.; Cho, K.; Lee, H.J.; Chang, S.; Lee, H.; Kim, J.H.; Koh, W.G. Highly conductive and hydrated PEG-based hydrogels for the potential application of a tissue engineering scaffold. React. Funct. Polym. 2016, 109, 15–22.

- Fallahi, A.; Mandla, S.; Kerr-Phillip, T.; Seo, J.; Rodrigues, R.O.; Jodat, Y.A.; Samanipour, R.; Hussain, M.A.; Lee, C.K.; Bae, H.; et al. Flexible and Stretchable PEDOT-Embedded Hybrid Substrates for Bioengineering and Sensory Applications. ChemNanoMat 2019, 5, 729–737.

- Spencer, A.R.; Primbetova, A.; Koppes, A.N.; Koppes, R.A.; Fenniri, H.; Annabi, N. Electroconductive Gelatin Methacryloyl-PEDOT:PSS Composite Hydrogels: Design, Synthesis, and Properties. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 4, 1558–1567.

- Roshanbinfar, K.; Vogt, L.; Greber, B.; Diecke, S.; Boccaccini, A.R.; Scheibel, T.; Engel, F.B. Electroconductive Biohybrid Hydrogel for Enhanced Maturation and Beating Properties of Engineered Cardiac Tissues. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 28, 1803951.

- Yang, B.; Yao, F.; Ye, L.; Hao, T.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Dong, D.; Fang, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; et al. A conductive PEDOT/alginate porous scaffold as a platform to modulate the biological behaviors of brown adipose-derived stem cells. Biomater. Sci. 2020, 8, 3173–3185.

- Lei, Q.; He, J.; Li, D. Electrohydrodynamic 3D printing of layer-specifically oriented, multiscale conductive scaffolds for cardiac tissue engineering. Nanoscale 2019, 11, 15195–15205.

- Sikorski, P. Electroconductive scaffolds for tissue engineering applications. Biomater. Sci. 2020, 8, 5583–5588.

- Wu, Y.; Guo, L. Enhancement of intercellular electrical synchronization by conductive materials in cardiac tissue engineering. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2018, 65, 264–272.

- Fendyur, A.; Mazurski, N.; Shappir, J.; Spira, M.E. Formation of essential ultrastructural interface between cultured hippocampal cells and gold mushroom-shaped MEA- towards “IN-CELL” recordings from vertebrate neurons. Front. Neuroeng. 2011, 4, 14.

- Nerbonne, J.M.; Kass, R.S. Molecular physiology of cardiac repolarization. Physiol. Rev. 2005, 85, 1205–1253.

- Santana, L.F.; Cheng, E.P.; Lederer, W.J. How does the shape of the cardiac action potential control calcium signaling and contraction in the heart? J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2010, 49, 901–903.