| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bobbi Pritt | + 2222 word(s) | 2222 | 2021-09-08 03:28:39 | | | |

| 2 | Bruce Ren | -13 word(s) | 2209 | 2021-09-22 05:59:18 | | |

Video Upload Options

Cyclospora cayetanensis is an intestinal coccidian parasite transmitted to humans through the consumption of oocysts in fecally contaminated food and water. Infection is found worldwide and is highly endemic in tropical and subtropical regions with poor sanitation. Disease in developed countries is usually observed in travelers and in seasonal outbreaks associated with imported produce from endemic areas. Recently, summertime outbreaks in the United States have also been linked to locally grown produce. Cyclosporiasis causes a diarrheal illness which may be severe in infants, the elderly, and immunocompromised individuals. The increased adoption of highly sensitive molecular diagnostic tests, including commercially available multiplex panels for gastrointestinal pathogens, has facilitated the detection of infection and likely contributed to the increased reports of cases in developed countries.

1. Introduction

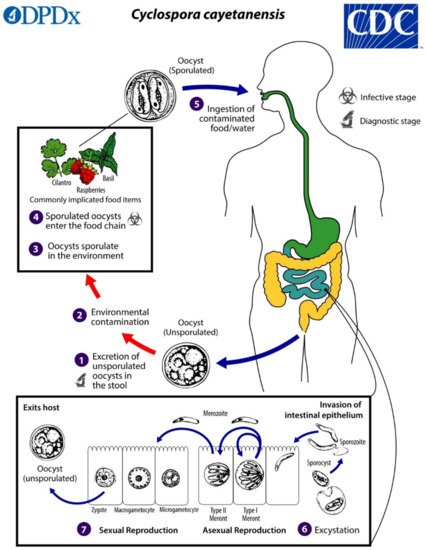

2. Biology and Life Cycle

3. Pathogenesis

4. Clinical Presentation

5. Treatment

6. Diagnosis

| Diagnostic Method | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Stool Microscopy | ||

| Direct wet mount | Fast, inexpensive; simultaneous detection of other intestinal parasites | Lack of sensitivity without concentration step; lack of defined morphologic features might make detection difficult for microscopists |

| Concentrated wet mount | Fast, inexpensive; simultaneous detection of other intestinal parasites | Lack of defined morphologic features might make detection difficult for microscopists |

| Differential Interference Contrast (DIC) | Increased sensitivity by highlighting internal structures | Not routinely available in many diagnostic labs |

| Ultraviolet autofluorescence | More sensitive than permanent smears; simultaneous detection of other coccidian oocysts and several helminth eggs | Requires specific UV filters that may not be routinely present in diagnostic labs |

| Lacto-phenol cotton blue | Fast, inexpensive; may be advantageous in resource-poor areas where acid-fast staining is not available | Non-specific; likely false positives with fungal elements |

| Trichrome/iron hematoxylin stain | Simultaneous detection of other intestinal protozoans | Oocysts do not stain with trichrome |

| Modified Ziehl-Neelsen (ZN) stain | Increased sensitivity over traditional O&P exams | Inconsistent staining of oocysts |

| Kinyoun’s modified acid-fast (MAF) stain | Increased sensitivity over traditional O&P exams | Inconsistent staining of oocysts |

| Modified safranin | More consistent staining of oocysts over ZN and MAF | Requires heating of stain |

| Auramine O (auramine-phenol) | More sensitive than traditional O&P exams | May be less sensitive than MAF, ZN; requires fluorescent microscope |

| Histopathology | ||

| Hematoxylin-and-eosin (H&E), periodic acid Schiff (PAS) | Identify multiple developmental stages of C. cayetanensis | Not routinely ordered for C. cayetanensis; may be difficult to distinguish from Cystoisospora belli |

| Ziehl–Neelsen stain, Fite’s acid-fast stain | Can detect oocysts in tissues | Pre-oocyst stages may not stain |

References

- Eberhard, M.L.; da Silva, A.J.; Lilley, B.G.; Pieniazek, N.J. Morphologic and molecular characterization of new Cyclospora species from Ethiopian monkeys: C. cercopitheci sp.n. C. colobi sp.n. and C. papionis sp.n. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 1999, 5, 651–658.

- Marangi, M.; Koehler, A.V.; Zanzani, S.A.; Manfredi, M.T.; Brianti, E.; Giangaspero, A.; Gasser, R.B. Detection of Cyclospora in captive chimpanzees and macaques by a quantitative PCR-based mutation scanning approach. Parasit. Vectors 2015, 8, 274.

- Almeria, S.; Cinar, H.N.; Dubey, J.P. Cyclospora cayetanensis and Cyclosporiasis: An Update. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 317.

- Ortega, Y.R.; Sanchez, R. Update on Cyclospora cayetanensis, a food-borne and waterborne parasite. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2010, 23, 218–234.

- CFIA-PHAC Public Health Notice-Outbreak of Cyclospora Infections under Investigation, October 11, 2017-Final Update. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/public-health-notices/2017/public-health-notice-outbreak-cyclospora-infections-under-investigation.html (accessed on 30 April 2021).

- Dixon, B.; Mihajlovic, B.; Couture, H.; Farber, J.M. Qualitative risk assessment: Cyclospora cayetanensis on fresh raspberries and blackberries imported into Canada. Food Prot. Trends 2016, 36, 18–32.

- Nichols, G.L.; Freedman, J.; Pollock, K.G.; Rumble, C.; Chalmers, R.M.; Chiodini, P.; Hawkins, G.; Alexander, C.L.; Godbole, G.; Williams, C.; et al. Cyclospora infection linked to travel to Mexico, June to September 2015. Euro Surveill 2015, 20.

- CFIA-PHAC Public Health Notice: Outbreak of Cyclospora Infections Linked to Salad Products and Fresh Herbs. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/public-health-notices/2020/outbreak-cyclospora-infections-salad-products.html (accessed on 30 April 2021).

- Bednarska, M.; Bajer, A.; Welc-Faleciak, R.; Pawelas, A. Cyclospora cayetanensis infection in transplant traveller: A case report of outbreak. Parasit. Vectors 2015, 8, 411.

- Abanyie, F.; Harvey, R.R.; Harris, J.R.; Wiegand, R.E.; Gaul, L.; Desvignes-Kendrick, M.; Irvin, K.; Williams, I.; Hall, R.L.; Herwaldt, B.; et al. 2013 multistate outbreaks of Cyclospora cayetanensis infections associated with fresh produce: Focus on the Texas investigations. Epidemiol. Infect. 2015, 143, 3451–3458.

- Casillas, S.M.; Bennett, C.; Straily, A. Notes from the Field: Multiple Cyclosporiasis Outbreaks-United States, 2018. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2018, 67, 1101–1102.

- Casillas, S.M.; Hall, R.L.; Herwaldt, B.L. Cyclosporiasis Surveillance-United States, 2011–2015. MMWR Surveill. Summ. 2019, 68, 1–16.

- CDC. U.S. Foodborne Outbreaks of Cyclosporiasis-2000–2017. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/cyclosporiasis/outbreaks/foodborneoutbreaks.html (accessed on 30 April 2021).

- CDC. Domestically Acquired Cases of Cyclosporiasis-United States, May–August 2018. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/cyclosporiasis/outbreaks/2018/c-082318/index.html (accessed on 30 April 2021).

- CDC. Multistate Outbreak of Cyclosporiasis Linked to Fresh Express Salad Mix Sold at McDonald’s Restaurants—United States, 2018: Final Update. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/cyclosporiasis/outbreaks/2018/b-071318/index.html (accessed on 30 April 2021).

- CDC. Multistate Outbreak of Cyclosporiasis Linked to Del Monte Fresh Produce Vegetable Trays—United States, 2018: Final Update. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/cyclosporiasis/outbreaks/2018/a-062018/index.html (accessed on 30 April 2021).

- CDC. Outbreak of Cyclospora Infections Linked to Bagged Salad Mix. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/cyclosporiasis/outbreaks/2020/ (accessed on 30 April 2021).

- CDC. Cyclosporiasis-Outbreak Investigations and Updates. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/cyclosporiasis/outbreaks/index.html (accessed on 22 July 2021).

- FDA. Cyclospora Prevention, Response and Research Action Plan. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/food/foodborne-pathogens/cyclospora-prevention-response-and-research-action-plan (accessed on 22 July 2021).

- Cama, V.A.; Mathison, B.A. Infections by Intestinal Coccidia and Giardia duodenalis. Clin. Lab. Med. 2015, 35, 423–444.

- Smith, H.V.; Paton, C.A.; Mitambo, M.M.; Girdwood, R.W. Sporulation of Cyclospora sp. oocysts. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1997, 63, 1631–1632.

- de Gorgolas, M.; Fortes, J.; Guerrero, M.L.F. Cyclospora cayetanensis Cholecystitis in a Patient with AIDS. Ann. Intern. Med. 2001, 134, 166.

- Sifuentes-Osornio, J.; Porras-Cortés, G.; Bendall, R.P.; Morales-Villarreal, F.; Reyes-Terán, G.; Ruiz-Palacios, G.M. Cyclospora cayetanensis Infection in Patients with and Without AIDS: Biliary Disease as Another Clinical Manifestation. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1995, 21, 1092–1097.

- Zar, F.A.; El-Bayoumi, E.; Yungbluth, M.M. Histologic Proof of Acalculous Cholecystitis Due to Cyclospora cayetanensis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2001, 33, e140–e141.

- Giangaspero, A.; Gasser, R.B. Human cyclosporiasis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, e226–e236.

- Sun, T.; Ilardi, C.F.; Asnis, D.; Bresciani, A.R.; Goldenberg, S.; Roberts, B.; Teichberg, S. Light and electron microscopic identification of Cyclospora species in the small intestine. Evidence of the presence of asexual life cycle in human host. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 1996, 105, 216–220.

- Fleming, C.A.; Caron, D.; Gunn, J.E.; Barry, M.A. A foodborne outbreak of Cyclospora cayetanensis at a wedding: Clinical features and risk factors for illness. Arch. Intern. Med. 1998, 158, 1121–1125.

- Herwaldt, B.L.; Ackers, M.L. An outbreak in 1996 of cyclosporiasis associated with imported raspberries. The Cyclospora Working Group. N. Engl. J. Med. 1997, 336, 1548–1556.

- Hoge, C.W.; Shlim, D.R.; Ghimire, M.; Rabold, J.G.; Pandey, P.; Walch, A.; Rajah, R.; Gaudio, P.; Echeverria, P. Placebo-controlled trial of co-trimoxazole for Cyclospora infections among travellers and foreign residents in Nepal. Lancet 1995, 345, 691–693.

- Huang, P.; Weber, J.T.; Sosin, D.M.; Griffin, P.M.; Long, E.G.; Murphy, J.J.; Kocka, F.; Peters, C.; Kallick, C. The first reported outbreak of diarrheal illness associated with Cyclospora in the United States. Ann. Intern. Med. 1995, 123, 409–414.

- CDC, Treatment for Cyclosporiasis. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/cyclosporiasis/health_professionals/tx.html (accessed on 22 July 2021).

- Medical Letter. The Medical Letter: Drugs for Parasitic Infections, 3rd ed.; The Medical Letter, Inc.: New Rochelle, NY, USA, 2013.

- Verdier, R.I.; Fitzgerald, D.W.; Johnson, W.D., Jr.; Pape, J.W. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole compared with ciprofloxacin for treatment and prophylaxis of Isospora belli and Cyclospora cayetanensis infection in HIV-infected patients. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 2000, 132, 885–888.

- Pape, J.W.; Verdier, R.-I.; Boncy, M.; Boncy, J.; Johnson, W.D. Cyclospora Infection in Adults Infected with HIV: Clinical Manifestations, Treatment, and Prophylaxis. Ann. Intern. Med. 1994, 121, 654–657.

- CDC. Chapter 2-Preparing Interntional Travelers. In CDC Yellow Book; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK. Available online: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2020/preparing-international-travelers/food-and-water-precautions (accessed on 22 July 2021).

- La Hoz, R.M.; Morris, M.I.; AST Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Intestinal parasites including Cryptosporidium, Cyclospora, Giardia, and Microsporidia, Entamoeba histolytica, Strongyloides, Schistosomiasis, and Echinococcus: Guidelines from the American Society of Transplantation Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Clin. Transplant 2019, 33, e13618.

- NIH HIV.gov-Clinical Guidelines. Available online: https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines (accessed on 22 July 2021).

- Garcia, L.S.; Arrowood, M.; Kokoskin, E.; Paltridge, G.P.; Pillai, D.R.; Procop, G.W.; Ryan, N.; Shimizu, R.Y.; Visvesvara, G. Laboratory Diagnosis of Parasites from the Gastrointestinal Tract. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2018, 31, e00025-17.