| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Julie GIRAUD | + 2406 word(s) | 2406 | 2021-09-03 11:22:43 |

Video Upload Options

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a difficult to treat liver cancer that generally arises in individuals suffering from alcoholic or non-alcoholic fatty liver diseases. Inflammation, tissue injury and fibrosis are important precursors of HCC. Translocation of microbial- and danger-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs and DAMPs) from the gut to the liver elicits profound chronic inflammation, leading to severe hepatic injury and eventually HCC progression.

1. Gut–Liver Communications

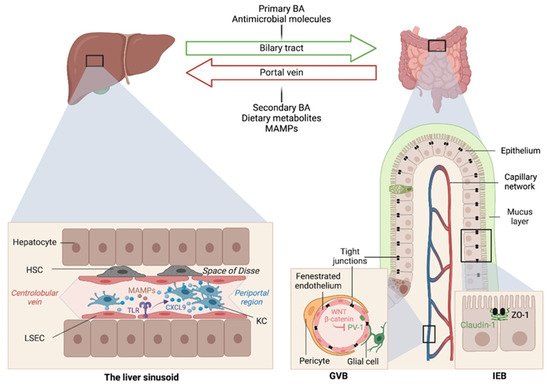

The liver is intimately linked to the gut and represents a critical metabolic hub involved in digestion, detoxification and clearance of microbial products. Its building blocks are the hepatic lobules organized around central veins and portal triads, consisting of a portal vein, a hepatic artery and a bile duct. The portal vein delivers 80% of the total liver blood supply, while the remaining 20%, i.e., the oxygenated blood, flows through the hepatic artery. Upon mixing, the blood flows across the lobule through the hepatic sinusoids and drains into the central veins, while the bile flows in the opposite direction via the bile canaliculi. Such an organization establishes gradients of oxygen and metabolites and creates a liver zonation. The hepatocytes, endothelial and immune cells of the liver are aligned along this vasculature, and their spatial distribution along the liver zonation dictates their phenotypes and functions.

2. The Central Role of the Gut Microbiome in Liver Diseases

At birth, we are colonized by a collection of microorganisms, including bacteria, fungi, viruses and archaea, that outnumber our human cells by 10:1 and provide 100-fold as many genes as found in our human genome [1]. The gut microbiota provide essential functions for our digestion and nutrient absorption, including the breakdown of indigestible carbohydrates, the synthesis of vitamins and the deconjugation of primary BA, and in shaping our mucosal immune system.

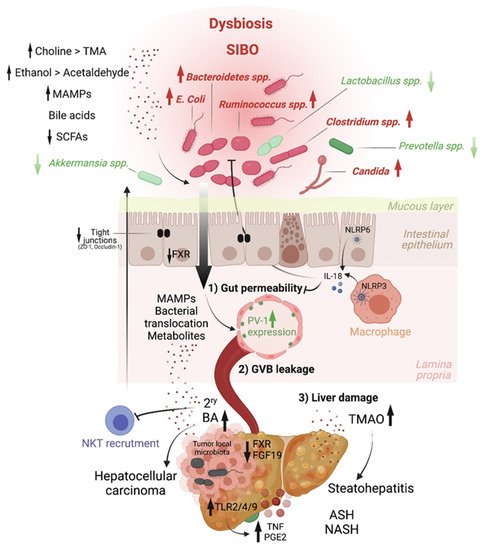

Altered intestinal microbiota, accompanied by small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), are observed in liver chronic inflammatory diseases [2][3][4], cirrhosis [5][6][7][8][9] and HCC [10], and gut microbiome metagenomic signatures have been identified in patients with NAFLD [11], cirrhosis [3] and HCC [12]. For instance, Boursier et al. reported that fecal Bacteroides and Ruminococcus were independently associated with NASH and fibrosis (stage 2 or higher), respectively, while Prevotella was depleted in these conditions [7]. Loomba and colleagues showed an increased abundance of Bacteroides vulgatus and Escherichia coli in NAFLD patients with advanced fibrosis [11]. Of note, E. coli is the predominant bacterium detected by culture in NAFLD patients exhibiting SIBO [2]. In mice, prolonged high dietary cholesterol feeding caused spontaneous NAFLD and progression to HCC development, which was associated with gut-microbiota dysbiosis [13]. Importantly, treatment with a cholesterol-lowering drug restored the microbial ecology and prevented disease development in mice [13]. In mouse models of NASH or obesity-induced HCC, Akkermansia spp., Prevotella spp. and Lactobacillus spp. are decreased, while Bacteroides spp., Clostridium spp. and Ruminococcus spp. are elevated [14][15][16] (Figure 2). Last, besides bacteria, the intestinal microbiota diversity is reduced in patients with liver diseases, particularly ALD patients, in whom candida dominates [17]

3. Intestinal Permeability as a Precursor of Liver Diseases

Early studies have reported a link between liver diseases and disrupted intestinal epithelial cell (IEC) barrier integrity. For instance, NAFLD patients with no significant alcohol consumption were shown to exhibit disrupted IEC tight junctions and increased prevalence of SIBO, which correlated with the severity of steatosis [21]. Similarly, both in vitro and in vivo studies demonstrated the impact of alcohol on enhancing intestinal permeability by altering the expression of the tight junction proteins zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1) and claudin-1 [22][23]. Consistently, occludin deficiency in mice led to a more severe ALD phenotype [23]. Besides the IEC barrier, a gut vascular barrier (GVB), as described by the Rescigno lab [24], also restricts liver injury and the translocation of bacteria or bacterial products into the systemic circulation. The GVB is composed of intestinal endothelial cells closely associated with pericytes and enteric glial cells and is thought to provide an additional protective layer that shields the liver from microbial moieties and inflammatory damage [25]. The integrity of the GVB is sustained by the activation of the WNT/β-catenin pathway, which inhibits the expression of the plasmalemma-vesicle-associated protein 1 (PV-1) [24], a membrane glycoprotein associated with the structure of fenestrated endothelia [26], and upregulated in leaky GVB [24] (Figure 1).

It is posited that gut microbiota dysbiosis results in reduced BA-mediated stimulation of the farnesoid X receptor (FXR) that drives β-catenin activation in endothelial cells. This has been demonstrated in mouse models of NASH induced by a HFD or a choline and methionine deficient (MCD) diet [27], and a mouse model of cirrhosis induced by bile duct ligation combined with carbon tetrachloride (CCL4)-mediated liver injury [28]. In both models, intestinal permeability led to microbial translocation from the gut to the liver, and FXR agonists, such as the BA analog obeticholic acid (OCA), conferred protection against GVB disruption, limited bacterial translocation and ameliorated liver pathology[29][30].

4. MAMPs and PRR Activation Link Microbiota Dysbiosis to Liver Inflammation and HCC

5. Host–Microbiome Metabolic Interactions in Liver Pathologies: A Focus on Bile Acids, Short Chain Fatty Acids, Choline and Ethanol Metabolites.

Short Chain Fatty Acids. SCFAs, which are produced by bacterial fermentation of dietary fibers, have been recently implicated in HCC. SCFAs, including butyrate, propionate and acetate, are generally associated with metabolic health [52]. For instance, in a randomized controlled trial that administered the fermentable fiber inulin coupled to a propionate ester to overweight adults reported decreased abdominal adiposity, lipid accumulation in the liver and body weight gain compared to controls receiving inulin alone [53].

This effect could be mediated by enhanced fat acid oxidation and energy metabolism, as shown in a second trial in which a mixture of SCFAs was infused in the colon of overweight or obese men [54]. Butyrate and propionate production are also altered in ALD. The reduction of butyrate is associated with a weakness of intestinal permeability, while the administration of butyrate in the form of tributyrin reduced intestinal permeability and subsequent liver injury in ethanol-fed mice [55]. However, this notion has been recently challenged by the group of Vijay-Kumar, who showed that large amounts of SCFA, particularly butyrate in a context of dysbiosis, may instead create a tumor-promoting environment. They reported that, while inulin protected mice from obesity, a longer period of inulin feeding, i.e., over 6 months, promoted cholestatic HCC in 40% of TLR5-deficient mice with a pre-existing dysbiotic microbiota [56]. Soluble-fiber-induced HCC was shown to be microbiota-dependent and transmissible to wild-type (WT) mice in cohousing or cross-fostering experiments. More importantly, interventions that deplete butyrate-producing bacteria, e.g., with metronidazole, inhibit gut fermentation, e.g., via supplementation of plant-derived -acids, exclude soluble fiber from the diet, or prevent enterohepatic recycling of BAs with cholestyramine reverted inulin-induced HCC in these mice [56].

Choline. Another host–microbiota-controlled metabolite is the macronutrient choline. Choline processing into phosphatidylcholine by the host prevents steatosis. Indeed, feeding mice a choline-deficient diet is a classical model of NASH. Alternatively, choline can be converted into trimethylamine (TMA) by intestinal bacteria, and it is then further metabolized in the liver into trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO). In contrast to phosphatidylcholine, TMAO is at the origin of hepatic steatosis by promoting triglyceride accumulation (Figure 2). Increased systemic circulation of TMAO is associated with a reduced level of phosphatidylcholine, and this imbalance is characteristic of patients with NAFLD [57] and NASH [58][59].

Ethanol. Ethanol metabolism greatly impacts HCC development through different mechanisms. The commensal microorganisms express genes that can ferment dietary sugars into ethanol that is absorbed by the gastrointestinal tract by simple diffusion. Moreover, liver cells, enterocytes and gut microbiota components express alcohol dehydrogenase, which co-metabolizes ethanol into toxic acetaldehyde that is then converted by CYP2E1—if this pathway is not saturated—to acetate. Acetaldehyde has been involved in weakening tight junctions of the intestinal epithelial barrier [23], eliciting gut barrier permeability and enabling translocation of microbial products, as shown in ethanol-fed mice [60]. In addition, ethanol exacerbates oxidative stress and hepatic inflammation and is a known carcinogen [61].

6. Conclusion

While much progress has been made in this field, for instance, in cataloguing enriched or depleted microorganisms in health versus disease, we now need to move to next-generation studies of the functional microbiome in order to be able to design microbial strategies to counter liver diseases and HCC.

References

- Ethan Hillman; Hang Lu; Tianming Yao; Cindy H. Nakatsu; Microbial Ecology along the Gastrointestinal Tract. Microbes and Environments 2017, 32, 300-313, 10.1264/jsme2.me17017.

- Kapil, S.; Duseja, A.; Sharma, B.K.; Singla, B.; Chakraborti, A.; Das, A.; Ray, P.; Dhiman, R.K.; Chawla, Y. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth and toll-like receptor signaling in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2015, 31, 213–221.

- Caussy, C.; Tripathi, A.; Humphrey, G.; Bassirian, S.; Singh, S.; Faulkner, C.; Bettencourt, R.; Rizo, E.; Richards, L.; Xu, Z.Z.; et al. A gut microbiome signature for cirrhosis due to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1406.

- Behary, J.; Amorim, N.; Jiang, X.-T.; Raposo, A.; Gong, L.; McGovern, E.; Ibrahim, R.; Chu, F.; Stephens, C.; Jebeili, H.; et al. Gut microbiota impact on the peripheral immune response in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease related hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 187.

- Qin, N.; Yang, F.; Li, A.; Prifti, E.; Chen, Y.; Shao, L.; Guo, J.; Le Chatelier, E.; Yao, J.; Wu, L.; et al. Alterations of the human gut microbiome in liver cirrhosis. Nature 2014, 513, 59–64.

- Bajaj, J.S.; Betrapally, N.; Hylemon, P.B.; Heuman, D.M.; Daita, K.; White, M.B.; Unser, A.; Thacker, L.R.; Sanyal, A.J.; Kang, D.J.; et al. Salivary microbiota reflects changes in gut microbiota in cirrhosis with hepatic encephalopathy. Hepatology 2015, 62, 1260–1271.

- Boursier, J.; Mueller, O.; Barret, M.; Machado, M.V.; Fizanne, L.; Araujo-Perez, F.; Guy, C.D.; Seed, P.C.; Rawls, J.F.; David, L.A.; et al. The severity of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is associated with gut dysbiosis and shift in the metabolic function of the gut microbiota. Hepatology 2015, 63, 764–775.

- Chen, Y.; Ji, F.; Guo, J.; Shi, D.; Fang, D.; Li, L. Dysbiosis of small intestinal microbiota in liver cirrhosis and its association with etiology. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 34055.

- Oh, T.G.; Kim, S.M.; Caussy, C.; Fu, T.; Guo, J.; Bassirian, S.; Singh, S.; Madamba, E.V.; Bettencourt, R.; Richards, L.; et al. A Universal Gut-Microbiome-Derived Signature Predicts Cirrhosis. Cell Metab. 2020, 32, 878–888.e6.

- Ponziani, F.R.; Bhoori, S.; Castelli, C.; Putignani, L.; Rivoltini, L.; Del Chierico, F.; Sanguinetti, M.; Morelli, D.; Sterbini, F.P.; Petito, V.; et al. Hepatocellular Carcinoma Is Associated With Gut Microbiota Profile and Inflammation in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Hepatology 2018, 69, 107–120.

- Loomba, R.; Seguritan, V.; Li, W.; Long, T.; Klitgord, N.; Bhatt, A.; Dulai, P.S.; Caussy, C.; Bettencourt, R.; Highlander, S.K.; et al. Gut Microbiome-Based Metagenomic Signature for Non-invasive Detection of Advanced Fibrosis in Human Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Cell Metab. 2017, 25, 1054–1062.e5.

- Albhaisi, S.; Shamsaddini, A.; Fagan, A.; McGeorge, S.; Sikaroodi, M.; Gavis, E.; Patel, S.; Davis, B.C.; Acharya, C.; Sterling, R.K.; et al. Gut Microbial Signature of Hepatocellular Cancer in Men with Cirrhosis. Liver Transplant. 2021, 27, 629–640.

- Zhang, X.; Coker, O.O.; Chu, E.S.; Fu, K.; Lau, H.C.H.; Wang, Y.-X.; Chan, A.W.H.; Wei, H.; Yang, X.; Sung, J.J.Y.; et al. Dietary cholesterol drives fatty liver-associated liver cancer by modulating gut microbiota and metabolites. Gut 2020, 70, 761–774.

- Yoshimoto, S.; Loo, T.M.; Atarashi, K.; Kanda, H.; Sato, S.; Oyadomari, S.; Iwakura, Y.; Oshima, K.; Morita, H.; Hattori, M.; et al. Obesity-induced gut microbial metabolite promotes liver cancer through senescence secretome. Nature 2013, 499, 97–101.

- Xie, G.; Wang, X.; Liu, P.; Wei, R.; Chen, W.; Rajani, C.; Hernandez, B.Y.; Alegado, R.; Dong, B.; Li, D.; et al. Distinctly altered gut microbiota in the progression of liver disease. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 19355–19366.

- Xie, G.; Wang, X.; Huang, F.; Zhao, A.; Chen, W.; Yan, J.; Zhang, Y.; Lei, S.; Ge, K.; Zheng, X.; et al. Dysregulated hepatic bile acids collaboratively promote liver carcinogenesis. Int. J. Cancer 2016, 139, 1764–1775.

- Shoji Yamada; Yoko Takashina; Mitsuhiro Watanabe; Ryogo Nagamine; Yoshimasa Saito; Nobuhiko Kamada; Hiedtsugu Saito; Bile acid metabolism regulated by the gut microbiota promotes non-alcoholic steatohepatitis-associated hepatocellular carcinoma in mice. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 9925-9939, 10.18632/oncotarget.24066.

- Yamada, S.; Takashina, Y.; Watanabe, M.; Nagamine, R.; Saito, Y.; Kamada, N.; Saito, H. Bile acid metabolism regulated by the gut microbiota promotes non-alcoholic steatohepatitis-associated hepatocellular carcinoma in mice. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 9925–9939.

- Zheng, Y.; Wang, T.; Tu, X.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Tan, D.; Jiang, W.; Cai, S.; Zhao, P.; Song, R.; et al. Gut microbiome affects the response to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Immunother. Cancer 2019, 7, 193.

- Silvia Sookoian; Adrian Salatino; Gustavo Osvaldo Castaño; Maria Silvia Landa; Cinthia Fijalkowky; Martin Garaycoechea; Carlos Jose Pirola; Intrahepatic bacterial metataxonomic signature in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Gut 2020, 69, 1483-1491, 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-318811.

- Miele, L.; Valenza, V.; La Torre, G.; Montalto, M.; Cammarota, G.; Ricci, R.; Mascianà, R.; Forgione, A.; Gabrieli, M.L.; Perotti, G.; et al. Increased intestinal permeability and tight junction alterations in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2009, 49, 1877–1887.

- Wang, Y.; Tong, J.; Chang, B.; Wang, B.; Zhang, D.; Wang, B. Effects of alcohol on intestinal epithelial barrier permeability and expression of tight junction-associated proteins. Mol. Med. Rep. 2014, 9, 2352–2356.

- Mir, H.; Meena, A.S.; Chaudhry, K.; Shukla, P.K.; Gangwar, R.; Manda, B.; Padala, M.K.; Shen, L.; Turner, J.R.; Dietrich, P.; et al. Occludin deficiency promotes ethanol-induced disruption of colonic epithelial junctions, gut barrier dysfunction and liver damage in mice. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 2015, 1860, 765–774.

- Spadoni, I.; Zagato, E.; Bertocchi, A.; Paolinelli, R.; Hot, E.; Di Sabatino, A.; Caprioli, F.; Bottiglieri, L.; Oldani, A.; Viale, G.; et al. A gut-vascular barrier controls the systemic dissemination of bacteria. Science 2015, 350, 830–834.

- Spadoni, I.; Fornasa, G.; Rescigno, M. Organ-specific protection mediated by cooperation between vascular and epithelial barriers. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2017, 17, 761–773.

- Stan, R.; Kubitza, M.; Palade, G.E. PV-1 is a component of the fenestral and stomatal diaphragms in fenestrated endothelia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 13203–13207.

- Mouries, J.; Brescia, P.; Silvestri, A.; Spadoni, I.; Sorribas, M.; Wiest, R.; Mileti, E.; Galbiati, M.; Invernizzi, P.; Adorini, L.; et al. Microbiota-driven gut vascular barrier disruption is a prerequisite for non-alcoholic steatohepatitis development. J. Hepatol. 2019, 71, 1216–1228.

- Sorribas, M.; Jakob, M.O.; Yilmaz, B.; Li, H.; Stutz, D.; Noser, Y.; de Gottardi, A.; Moghadamrad, S.; Hassan, M.; Albillos, A.; et al. FXR modulates the gut-vascular barrier by regulating the entry sites for bacterial translocation in experimental cirrhosis. J. Hepatol. 2019, 71, 1126–1140.

- Juliette Mouries; Paola Brescia; Alessandra Silvestri; Ilaria Spadoni; Marcel Sorribas; Reiner Wiest; Erika Mileti; Marianna Galbiati; Pietro Invernizzi; Luciano Adorini; et al.Giuseppe PennaMaria Rescigno Microbiota-driven gut vascular barrier disruption is a prerequisite for non-alcoholic steatohepatitis development. Journal of Hepatology 2019, 71, 1216-1228, 10.1016/j.jhep.2019.08.005.

- Marcel Sorribas; Manuel O. Jakob; Bahtiyar Yilmaz; Hai Li; David Stutz; Yannik Noser; Andrea de Gottardi; Sheida Moghadamrad; Moshin Hassan; Agustin Albillos; et al.Ruben FrancésOriol JuanolaIlaria SpadoniMaria RescignoReiner Wiest FXR modulates the gut-vascular barrier by regulating the entry sites for bacterial translocation in experimental cirrhosis. Journal of Hepatology 2019, 71, 1126-1140, 10.1016/j.jhep.2019.06.017.

- Paik, Y.; Schwabe, R.F.; Bataller, R.; Russo, M.P.; Jobin, C.; Brenner, D. Toll-Like receptor 4 mediates inflammatory signaling by bacterial lipopolysaccharide in human hepatic stellate cells. Hepatology 2003, 37, 1043–1055.

- Seki, E.; De Minicis, S.; Osterreicher, C.H.; Kluwe, J.; Osawa, Y.; Brenner, D.A.; Schwabe, R.F. TLR4 enhances TGF-beta signaling and hepatic fibrosis. Nat. Med. 2007, 13, 1324–1332.

- Gäbele, E.; Mühlbauer, M.; Dorn, C.; Weiss, T.; Froh, M.; Schnabl, B.; Wiest, R.; Schölmerich, J.; Obermeier, F.; Hellerbrand, C. Role of TLR9 in hepatic stellate cells and experimental liver fibrosis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008, 376, 271–276.

- Hartmann, P.; Haimerl, M.; Mazagova, M.; Brenner, D.; Schnabl, B. Toll-Like Receptor 2–Mediated Intestinal Injury and Enteric Tumor Necrosis Factor Receptor I Contribute to Liver Fibrosis in Mice. Gastroenterology 2012, 143, 1330–1340.e1.

- Loo, T.M.; Kamachi, F.; Watanabe, Y.; Yoshimoto, S.; Kanda, H.; Arai, Y.; Nakajima-Takagi, Y.; Iwama, A.; Koga, T.; Sugimoto, Y.; et al. Gut Microbiota Promotes Obesity-Associated Liver Cancer through PGE2-Mediated Suppression of Antitumor Immunity. Cancer Discov. 2017, 7, 522–538.

- Dapito, D.H.; Mencin, A.; Gwak, G.-Y.; Pradère, J.-P.; Jang, M.-K.; Mederacke, I.; Caviglia, J.M.; Khiabanian, H.; Adeyemi, A.; Bataller, R.; et al. Promotion of Hepatocellular Carcinoma by the Intestinal Microbiota and TLR4. Cancer Cell 2012, 21, 504–516.

- Payne, C.M.; Weber, C.; Crowley-Skillicorn, C.; Dvorak, K.; Bernstein, H.; Bernstein, C.; Holubec, H.; Dvorakova, B.; Garewal, H. Deoxycholate induces mitochondrial oxidative stress and activates NF-kappaB through multiple mechanisms in HCT-116 colon epithelial cells. Carcinogenesis 2007, 28, 215–222.

- Zucchini-Pascal, N.; De Sousa, G.; Pizzol, J.; Rahmani, R. Pregnane X receptor activation protects rat hepatocytes against deoxycholic acid-induced apoptosis. Liver Int. 2010, 30, 284–297.

- Takahashi, S.; Luo, Y.; Ranjit, S.; Xie, C.; Libby, A.E.; Orlicky, D.J.; Dvornikov, A.; Wang, X.X.; Myakala, K.; Jones, B.A.; et al. Bile acid sequestration reverses liver injury and prevents progression of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in Western diet–fed mice. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 4733–4747.

- Chávez-Talavera, O.; Tailleux, A.; Lefebvre, P.; Staels, B. Bile Acid Control of Metabolism and Inflammation in Obesity, Type 2 Diabetes, Dyslipidemia, and Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Gastroenterology 2017, 152, 1679–1694.e3.

- Pandak, W.M.; Kakiyama, G. The acidic pathway of bile acid synthesis: Not just an alternative pathway. Liver Res. 2019, 3, 88–98.

- Ridlon, J.M.; Harris, S.C.; Bhowmik, S.; Kang, D.-J.; Hylemon, P.B. Consequences of bile salt biotransformations by intestinal bacteria. Gut Microbes 2016, 7, 22–39.

- Postler, T.; Ghosh, S. Understanding the Holobiont: How Microbial Metabolites Affect Human Health and Shape the Immune System. Cell Metab. 2017, 26, 110–130.

- Fiorucci, S.; Distrutti, E. Bile Acid-Activated Receptors, Intestinal Microbiota, and the Treatment of Metabolic Disorders. Trends Mol. Med. 2015, 21, 702–714.

- Wahlström, A.; Sayin, S.I.; Marschall, H.-U.; Bäckhed, F. Intestinal Crosstalk between Bile Acids and Microbiota and Its Impact on Host Metabolism. Cell Metab. 2016, 24, 41–50.

- Sayin, S.I.; Wahlström, A.; Felin, J.; Jäntti, S.; Marschall, H.-U.; Bamberg, K.; Angelin, B.; Hyötyläinen, T.; Oresic, M.; Bäckhed, F. Gut Microbiota Regulates Bile Acid Metabolism by Reducing the Levels of Tauro-beta-muricholic Acid, a Naturally Occurring FXR Antagonist. Cell Metab. 2013, 17, 225–235.

- Mouzaki, M.; Wang, A.Y.; Bandsma, R.; Comelli, E.M.; Arendt, B.M.; Zhang, L.; Fung, S.; Fischer, S.E.; McGilvray, I.; Allard, J.P. Bile Acids and Dysbiosis in Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0151829.

- Hartmann, P.; Hochrath, K.; Horvath, A.; Chen, P.; Seebauer, C.T.; Llorente, C.; Wang, L.; Alnouti, Y.; Fouts, D.E.; Stärkel, P.; et al. Modulation of the intestinal bile acid/farnesoid X receptor/fibroblast growth factor 15 axis improves alcoholic liver disease in mice. Hepatology 2017, 67, 2150–2166.

- Ma, C.; Han, M.; Heinrich, B.; Fu, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Sandhu, M.; Agdashian, D.; Terabe, M.; Berzofsky, J.A.; Fako, V.; et al. Gut microbiome–mediated bile acid metabolism regulates liver cancer via NKT cells. Science 2018, 360, eaan5931.

- Hang, S.; Paik, D.; Yao, L.; Kim, E.; Trinath, J.; Lu, J.; Ha, S.; Nelson, B.N.; Kelly, S.P.; Wu, L.; et al. Bile acid metabolites control TH17 and Treg cell differentiation. Nature 2019, 576, 143–148, Erratum in 2020, 579, E7.

- Song, X.; Sun, X.; Oh, S.F.; Wu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, W.; Geva-Zatorsky, N.; Jupp, R.; Mathis, D.; Benoist, C.; et al. Microbial bile acid metabolites modulate gut RORgamma(+) regulatory T cell homeostasis. Nature 2020, 577, 410–415.

- Koh, A.; De Vadder, F.; Kovatcheva-Datchary, P.; Bäckhed, F. From Dietary Fiber to Host Physiology: Short-Chain Fatty Acids as Key Bacterial Metabolites. Cell 2016, 165, 1332–1345.

- Chambers, E.; Viardot, A.; Psichas, A.; Morrison, D.; Murphy, K.; Zac-Varghese, S.E.K.; MacDougall, K.; Preston, T.; Tedford, C.; Finlayson, G.S.; et al. Effects of targeted delivery of propionate to the human colon on appetite regulation, body weight maintenance and adiposity in overweight adults. Gut 2014, 64, 1744–1754.

- Emanuel E. Canfora; Christina M. Van Der Beek; Johan W. E. Jocken; Gijs Goossens; Jens Juul Holst; Steven Olde Damink; Kaatje Lenaerts; Cornelis H. C. DeJong; Ellen E. Blaak; Colonic infusions of short-chain fatty acid mixtures promote energy metabolism in overweight/obese men: a randomized crossover trial. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 1-12, 10.1038/s41598-017-02546-x.

- Gail A. Cresci; Bryan Glueck; Megan R. McMullen; Wei Xin; Daniella Allende; Laura E. Nagy; Prophylactic tributyrin treatment mitigates chronic-binge ethanol-induced intestinal barrier and liver injury. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2017, 32, 1587-1597, 10.1111/jgh.13731.

- Vishal Singh; Beng San Yeoh; Benoit Chassaing; Xia Xiao; Piu Saha; Rodrigo Aguilera Olvera; John D. Lapek; Limin Zhang; Wei-Bei Wang; Sijie Hao; et al.Michael D. FlytheDavid J. GonzalezPatrice D. CaniJose R. Conejo-GarciaNa XiongMary J. KennettBina JoeAndrew D. PattersonAndrew T. GewirtzMatam Vijay-Kumar Dysregulated Microbial Fermentation of Soluble Fiber Induces Cholestatic Liver Cancer. Cell 2018, 175, 679-694.e22, 10.1016/j.cell.2018.09.004.

- Arendt, B.M.; Ma, D.; Simons, B.; Noureldin, S.A.; Therapondos, G.; Guindi, M.; Sherman, M.; Allard, J.P. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is associated with lower hepatic and erythrocyte ratios of phosphatidylcholine to phosphatidylethanolamine. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2013, 38, 334–340.

- Chen, Y.-M.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, R.-F.; Chen, X.-L.; Wang, C.; Tan, X.-Y.; Wang, L.-J.; Zheng, R.-D.; Zhang, H.-W.; Ling, W.-H.; et al. Associations of gut-flora-dependent metabolite trimethylamine-N-oxide, betaine and choline with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in adults. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 19076.

- León-Mimila, P.; Villamil-Ramírez, H.; Li, X.S.; Shih, D.M.; Hui, S.T.; Ocampo-Medina, E.; López-Contreras, B.; Morán-Ramos, S.; Olivares-Arevalo, M.; Grandini-Rosales, P.; et al. Trimethylamine N-oxide levels are associated with NASH in obese subjects with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab. 2020, 47, 101183.

- Yan, A.W.; Schnabl, B. Bacterial translocation and changes in the intestinal microbiome associated with alcoholic liver disease. World J. Hepatol. 2012, 4, 110–118.

- Seitz, H.K.; Stickel, F. Molecular mechanisms of alcohol-mediated carcinogenesis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2007, 7, 599–612.