| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Rachael Murray | + 2189 word(s) | 2189 | 2021-08-18 09:53:40 | | | |

| 2 | Lindsay Dong | Meta information modification | 2189 | 2021-08-20 04:58:05 | | |

Video Upload Options

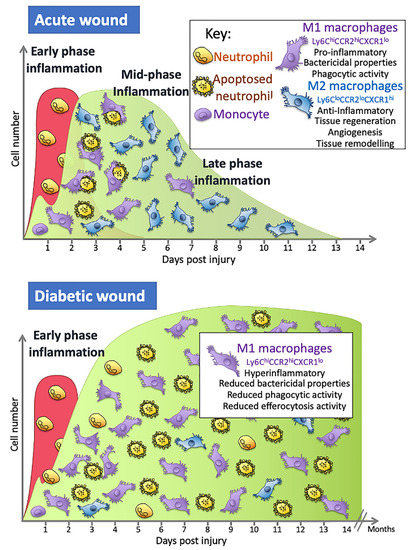

Macrophages play a prominent role in wound healing. In the early stages, they promote inflammation and remove pathogens, wound debris, and cells that have apoptosed. Later in the repair process, they dampen inflammation and secrete factors that regulate the proliferation, differentiation, and migration of keratinocytes, fibroblasts, and endothelial cells, leading to neovascularisation and wound closure. The macrophages that coordinate this repair process are complex: they originate from different sources and have distinct phenotypes with diverse functions that act at various times in the repair process. Macrophages in individuals with diabetes are altered, displaying hyperresponsiveness to inflammatory stimulants and increased secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines. They also have a reduced ability to phagocytose pathogens and efferocytose cells that have undergone apoptosis. This leads to a reduced capacity to remove pathogens and, as efferocytosis is a trigger for their phenotypic switch, it reduces the number of M2 reparative macrophages in the wound. This can lead to diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs) forming and contributes to their increased risk of not healing and becoming infected, and potentially, amputation.

1. Introduction

Non-healing ulcers are the most common cause of amputation and it is estimated that, worldwide, a leg is amputated due to diabetes every 30 seconds [1][2][3]. Approximately 84% of lower leg amputations will be in patients that have acquired a DFU prior to amputation [4][5].

Macrophages are one of the key cells that regulate the wound repair process [6][7]. Wounds without macrophages have delayed re-epithelialisation, impaired angiogenesis, reduced collagen deposition, and reduced cell proliferation [8]. They are not a homogenous population of cells and several different combinations of phenotypes with distinct functions present at different times in the repair process [6][9][10]. Macrophage function is altered in people with diabetes such that they have a reduced capacity to clear an infection and their function in the later stages of repair is altered, leading to a delay in the repair process [6][11][12][13][14][15].

2. Repair of an Acute Wound

3. The Inflammatory Phase of Wound Healing and Macrophages

Studies in mice show that wound monocyte/macrophage numbers dramatically increase in an acute wound and then remain high from day 2 until around day 5, although this timing is wound-size dependent, with larger wounds taking longer [22]. The numbers then begin to decrease as re-epithelialisation occurs, falling to relatively low levels by day 7 and then returning to steady-state levels by day 14 [22]. Over this day 2–7 period, these cells have many different functions and so are responsible for a wide range of effects: they contribute to the initiation of inflammation but also resolve inflammation; they remove any pathogens that may have entered the wound; they clear up the neutrophils containing dead and partially digested microbes which have apoptosed and the remaining cell and ECM debris; they orchestrate the repair process through their secretion of cytokines and other factors, such as TGF- β1 and VEGF, that promote angiogenesis and attract fibroblasts that secrete extracellular matrix components necessary to rebuild the tissue; and they secrete enzymes that play a role in remodelling the ECM [7][16].

Source and Plasticity of Wound Associated Macrophages

The monocytes/macrophages observed in wounds are derived from a number of sources. Initially, they consist of the tissue resident macrophages located in the skin prior to injury, of which there are two kinds; in the epidermal layer, these are predominantly Langerhans cells; in the dermal layer, they are mainly dermal macrophages [9].

Next on scene is the early wave of monocytes, which enter through microhaemorrhages caused by blood vessels damaged during the injury itself [22]. Factors released from platelets and in the wound environment trigger their differentiation into macrophages [23]. In the wound, these cells would also be exposed to alarmins, which include danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) such as HMGB-1 or ATP released from cells after tissue damage, that activate these cells to become M1 macrophages [24]. Once activated, they can contribute to the initial proinflammatory phase and help recruit bone marrow-derived monocytes from the circulation 24 h later in a process that involves the chemokine receptor present on macrophages, CX3CR1 [22]. To accommodate the recruitment of a significant number of monocyte cells from the blood, there is an increase in myeloid lineage committed multipotent progenitors and monocytes in bone marrow that results in a 70% increase in monocytes in circulation on day 2, with their levels returning to steady-state levels after around day 4 [22][25]. These monocytes are classified as either classical/pro-inflammatory monocytes that are CD14+CD16− capable of differentiating into pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages or anti-inflammatory monocytes that are CD14low/CD16+ that give rise to mostly M2 macrophages [19]. In mouse models of wound repair, circulating monocytes can also be divided into two groups: CX3CR1lowCCR2+ Ly6C+ and CX3CR1highCCR2−Ly6C− [7]. The first group produces pro-inflammatory cytokines and is the first to enter a wound, with the second entering later [7]. Factors in the local wound environment stimulate these bone marrow-derived monocytes to differentiate into macrophages and the precise combination of these factors is what appears to dictate macrophage phenotype, although the original phenotype of the bone marrow monocytes may also dictate the macrophage phenotype. In addition, some immune cells can proliferate in the wound [26]. It is the inflammatory monocytes/macrophages derived from the circulating monocytes, but not the mature wound macrophages, that are able to proliferate in the wound and, at the mid-stages of healing, these cells constitute around 25% of macrophage population.

4. Macrophage Dysregulation and the Repair Process

One common factor in all ulcers, both diabetic and non-diabetic, along with the inability to heal, is the dysregulation of the inflammatory phase of wound healing [15]. In diabetes, this is compounded by the fact that high levels of glucose seen in diabetes alters cells of the immune system, including macrophages, one of the key orchestrators of the repair process and defence against infection [13][27][28][29]. This dysregulation potentially contributes further to non-healing wounds and to the increased risk of infections. In individuals with diabetes, M1 macrophages drive the elevated and prolonged non-resolving inflammatory phase seen in DFUs [30]. Approximately 80% of cells at the chronic wound margin are pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages and there are compelling data from mouse and human studies to suggest that the shift to M2-like phenotypes may not proceed as expected, despite this shift being necessary for the repair process to progress [29][30].

Macrophage Function Is Altered in People with Diabetes

Hyperglycaemia leads to an increase in advanced glycation end products (AGEs), which are proteins or lipids glycated due to their exposure to sugars [32]. The diabetic wound environment accumulates both AGEs and macrophages that express high numbers of the receptor for AGEs (RAGE). In vitro, the addition of AGEs to M1 macrophages reduces their ability to phagocytose. The phagocytosis of apoptosed cells (efferocytosis) is a key process that activates the switch to M2 macrophages.

5. Concluding Remarks

References

- Armstrong, D.G.; Boulton, A.J.M.; Bus, S.A. Diabetic Foot Ulcers and Their Recurrence. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 2367–2375.

- Bakker, K.; van Houtum, W.H.; Riley, P.C. 2005: The International Diabetes Federation focuses on the diabetic foot. Curr. Diab. Rep. 2005, 5, 436–440.

- Lin, X.; Xu, Y.; Pan, X.; Xu, J.; Ding, Y.; Sun, X.; Song, X.; Ren, Y.; Shan, P.-F. Global, regional, and national burden and trend of diabetes in 195 countries and territories: An analysis from 1990 to 2025. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 14790.

- Boulton, A.J.M.; Vileikyte, L.; Ragnarson-Tennvall, G.; Apelqvist, J. The global burden of diabetic foot disease. Lancet 2005, 366, 1719–1724.

- Sinwar, P.D. The diabetic foot management—Recent advance. Int. J. Surg. 2015, 15, 27–30.

- Wolf, S.J.; Melvin, W.J.; Gallagher, K. Macrophage-mediated inflammation in diabetic wound repair. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 199, 17–24.

- Brancato, S.K.; Albina, J.E. Wound Macrophages as Key Regulators of Repair: Origin, Phenotype, and Function. Am. J. Pathol. 2011, 178, 19–25.

- Mirza, R.; DiPietro, L.A.; Koh, T.J. Selective and Specific Macrophage Ablation Is Detrimental to Wound Healing in Mice. Am. J. Pathol. 2009, 175, 2454–2462.

- Minutti, C.; Knipper, J.; Allen, J.E.; Zaiss, D.M. Tissue-specific contribution of macrophages to wound healing. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2017, 61, 3–11.

- Daley, J.M.; Brancato, S.K.; Thomay, A.A.; Reichner, J.; Albina, J.E. The phenotype of murine wound macrophages. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2009, 87, 59–67.

- Miao, M.; Niu, Y.; Xie, T.; Yuan, B.; Qing, C.; Lu, S. Diabetes-impaired wound healing and altered macro-phage activation: A possible pathophysiologic correlation. Wound Repair Regen. 2012, 20, 203–213.

- Lecube, A.; Pachón, G.; Petriz, J.; Hernández, C.; Simó, R. Phagocytic Activity Is Impaired in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Increases after Metabolic Improvement. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e23366.

- Ayala, T.S.; Tessaro, F.H.G.; Jannuzzi, G.P.; Bella, L.M.; Ferreira, K.S.; Martins, J.O. High Glucose Environments Interfere with Bone Marrow-Derived Macrophage Inflammatory Mediator Release, the TLR4 Path-way and Glucose Metabolism. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 11447.

- Doran, A.C.; Yurdagul, A.; Tabas, I. Efferocytosis in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 20, 254–267.

- Louiselle, A.E.; Niemiec, S.M.; Zgheib, C.; Liechty, K.W. Macrophage polarization and diabetic wound healing. Transl. Res. 2021.

- Hesketh, M.; Sahin, K.B.; West, Z.E.; Murray, R.Z. Macrophage Phenotypes Regulate Scar Formation and Chronic Wound Healing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1545.

- Rodrigues, M.; Kosaric, N.; Bonham, C.A.; Gurtner, G.C. Wound Healing: A Cellular Perspective. Physiol. Rev. 2019, 99, 665–706.

- Clark, R.A. Fibrin Is a Many Splendored Thing. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2003, 121, 1523–1747.

- Raziyeva, K.; Kim, Y.; Zharkinbekov, Z.; Kassymbek, K.; Jimi, S.; Saparov, A. Immunology of Acute and Chronic Wound Healing. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 700.

- Wilgus, T.A.; Roy, S.; McDaniel, J.C. Neutrophils and Wound Repair: Positive Actions and Negative Reactions. Adv. Wound Care 2013, 2, 379–388.

- Rodero, M.; Khosrotehrani, K. Skin wound healing modulation by macrophages. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2010, 3, 643–653.

- Rodero, M.P.; Hodgson, S.S.; Hollier, B.; Combadiere, C.; Khosrotehrani, K. Reduced Il17a expression distinguishes a Ly6c(lo)MHCII(hi) macrophage population promoting wound healing. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2013, 133, 783–792.

- Kral, J.B.; Schrottmaier, W.C.; Salzmann, M.; Assinger, A. Platelet interaction with innate immune cells. Transfus. Med. Hemother. 2016, 43, 78–88.

- Venereau, E.; Ceriotti, C.; Bianchi, M.E. DAMPs from Cell Death to New Life. Front. Immunol. 2015, 6, 422.

- Barman, P.K.; Pang, J.; Urao, N.; Koh, T.J. Skin Wounding-Induced Monocyte Expansion in Mice Is Not Abrogated by IL-1 Receptor 1 Deficiency. J. Immunol. 2019, 202, 2720–2727.

- Pang, J.; Urao, N.; Koh, T.J. Proliferation of Ly6C+ monocytes/macrophages contributes to their accumulation in mouse skin wounds. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2020, 107, 551–560.

- Bannon, P.; Wood, S.; Restivo, T.; Campbell, L.; Hardman, M.J.; Mace, K.A. Diabetes induces stable intrinsic changes to myeloid cells that contribute to chronic inflammation during wound healing in mice. Dis. Model. Mech. 2013, 6, 1434–1447.

- Delamaire, M.; Maugendre, D.; Moreno, M.; Le Goff, M.-C.; Allannic, H.; Genetet, B. Impaired Leucocyte Functions in Diabetic Patients. Diabet. Med. 1997, 14, 29–34.

- Khanna, S.; Biswas, S.; Shang, Y.; Collard, E.; Azad, A.; Kauh, C.; Bhasker, V.; Gordillo, G.M.; Sen, C.K.; Roy, S. Macrophage Dysfunction Impairs Resolution of Inflammation in the Wounds of Diabetic Mice. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e9539.

- Sindrilaru, A.; Peters, T.; Wieschalka, S.; Baican, C.; Baican, A.; Peter, H.; Hainzl, A.; Schatz, S.; Qi, Y.; Schlecht, A.; et al. An unrestrained proinflammatory M1 macrophage population induced by iron impairs wound healing in humans and mice. J. Clin. Investig. 2011, 121, 985–997.

- Liu, B.F.; Miyata, S.; Kojima, H.; Uriuhara, A.; Kusunoki, H.; Suzuki, K.; Kasuga, M. Low phagocytic activity of resident peritoneal macrophages in diabetic mice: Relevance to the formation of advanced glycation end products. Diabetes 1999, 48, 2074–2082.

- Rungratanawanich, W.; Qu, Y.; Wang, X.; Essa, M.M.; Song, B.-J. Advanced glycation end products (AGEs) and other adducts in aging-related diseases and alcohol-mediated tissue injury. Exp. Mol. Med. 2021, 53, 168–188.

- Mirza, R.E.; Fang, M.M.; Ennis, W.J.; Koh, T.J. Blocking interleukin-1beta induces a healing-associated wound macrophage phenotype and improves healing in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 2013, 62, 2579–2587.

- Mirza, R.; Koh, T.J. Dysregulation of monocyte/macrophage phenotype in wounds of diabetic mice. Cytokine 2011, 56, 256–264.

- Shook, B.; Xiao, E.; Kumamoto, Y.; Iwasaki, A.; Horsley, V. CD301b+ Macrophages Are Essential for Effective Skin Wound Healing. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2016, 136, 1885–1891.

- Klinkert, K.; Whelan, D.; Clover, A.J.P.; Leblond, A.L.; Kumar, A.H.S.; Caplice, N.M. Selective M2 Macrophage Depletion Leads to Prolonged Inflammation in Surgical Wounds. Eur. Surg. Res. 2017, 58, 109–120.

- Heydari, P.; Kharaziha, M.; Varshosaz, J.; Javanmard, S.H. Current knowledge of immunomodulation strategies for chronic skin wound repair. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2021.

- Mouritzen, M.V.; Petkovic, M.; Qvist, K.; Poulsen, S.S.; Alarico, S.; Leal, E.C.; Dalgaard, L.T.; Empadinhas, N.; Carvalho, E.; Jenssen, H. Improved diabetic wound healing by LFcinB is associated with relevant changes in the skin immune response and microbiota. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2021, 20, 726–739.

- Petkovic, M.; Mouritzen, M.; Mojsoska, B.; Jenssen, H. Immunomodulatory Properties of Host Defence Peptides in Skin Wound Healing. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 952.

- Kimura, S.; Tsuji, T. Mechanical and Immunological Regulation in Wound Healing and Skin Reconstruction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5474.

- Kharaziha, M.; Baidya, A.; Annabi, N. Rational Design of Immunomodulatory Hydrogels for Chronic Wound Healing. Adv. Mater. 2021, e2100176, 2100176.

- Strudwick, X.L.; Adams, D.H.; Pyne, N.T.; Samuel, M.S.; Murray, R.Z.; Cowin, A.J. Systemic Delivery of Anti-Integrin alphaL Antibodies Reduces Early Macrophage Recruitment, Inflammation, and Scar Formation in Murine Burn Wounds. Adv. Wound Care 2020, 9, 637–648.

- Goren, I.; Muller, E.; Schiefelbein, D.; Christen, U.; Pfeilschifter, J.; Muhl, H.; Frank, S. Systemic an-ti-TNFalpha treatment restores diabetes-impaired skin repair in ob/ob mice by inactivation of macrophages. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2007, 127, 2259–2267.