we examined the transcriptional regulation of the CaFtsH06 gene in the R9 thermo-tolerant pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) line. The results of qRT-PCR revealed that CaFtsH06 expression was rapidly induced by abiotic stress treatments, including heat, salt, and drought. The CaFtsH06 protein was localized to the mitochondria and cell membrane. Additionally, silencing CaFtsH06 increased the accumulation of malonaldehyde content, conductivity, hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) content, and the activity levels of superoxide dismutase and superoxide (·O2−), while total chlorophyll content decreased under these abiotic stresses. Furthermore, CaFtsH06 ectopic expression enhanced tolerance to heat, salt, and drought stresses, thus decreasing malondialdehyde, proline, H2O2, and ·O2− contents while superoxide dismutase activity and total chlorophyll content were increased in transgenic Arabidopsis. Similarly, the expression levels of other defense-related genes were much higher in the transgenic ectopic expression lines than WT plants. These results suggest that CaFtsH06 confers abiotic stress tolerance in peppers by interfering with the physiological indices through reducing the accumulation of reactive oxygen species, inducing the activities of stress-related enzymes and regulating the transcription of defense-related genes, among other mechanisms. The results of this study suggest that CaFtsH06 plays a very crucial role in the defense mechanisms of pepper plants to unfavorable environmental conditions and its regulatory network with other CaFtsH genes should be examined across variable environments

1. Introduction

As sessile organisms, plants endure limitations to their growth, development, and agricultural productivity caused by abiotic stresses such as drought, salinity, and high temperatures

[1][2][3]. Unfavorable circumstances produce a variety of morphological and physiological changes in plants, as well as considerable damage to membrane integrity and stability, which results in intracellular material exosmosis

[1][4][5]. Plants have a number of defense mechanisms enabling their long-term acclimation to adverse environmental conditions, such as changes in the levels of phytohormones and Ca

2+ content as well as reactive oxygen species (ROS) signaling and plant-programmed cell death (PCD)

[6][7]. Under stress conditions, ROS are induced, which leads to oxidative stress, and, interestingly, plants have evolved sophisticated adaptive systems at the molecular level, including antioxidants enzymes

[8].

Protein denaturation will occur as a result of the sustained high temperature, which may result in the loss of protein function. Under heat stress conditions, through the restoration and hydrolysis of protein regulation systems, these defense mechanisms work together to repair functional failure proteins to maintain normal metabolic mechanisms

[9]. Filamentation temperature-sensitive H (FtsH), which has an N-terminal transmembrane domain followed by an AAA domain

[10][11], is a member of the ATP-dependent protease hydrolysis system family, which has ATPase and molecular chaperone activity

[12][13]. Additionally, FtsH protease activity can degrade misfolded and mistranslated proteins and provide a control mechanism to remove dysfunctional proteins in cells as central elements of energy metabolic control systems

[14][15].

In higher plants, there are many members of the FtsH family. There are 12

FtsH genes in

Arabidopsis thaliana, with three proteins (FtsH3, FtsH4, and FtsH10) localized to the mitochondria, eight (FtsH1, FtsH2, FtsH5 to FtsH9 and FtsH12) targeted to the chloroplasts, and one (FtsH11) entering both the mitochondria and chloroplasts

[10][16][17]; these genes participate in a variety of abiotic stress responses such as those to heat shock, hypertonicity, light stress, and cold

[18][19][20][21][22]. AtFtsH6 protease degrades Lhcb3 and Lhcb1 so as to participate in senescence and high light acclimation

[23]. AtFtsH1 participates in the degradation of the 23 kDa peptide fragment of the D1 protein photooxidative damage product

[24]. In spinach, FtsH appears to be involved in D1 protein turnover in response to heat stress

[25].

FtsH is an energy-dependent protease that is required for the growth of many prokaryotes. The FtsH protease from

Escherichia coli can downregulate the heat shock response by degrading the heat shock transcription factor σ

32 [26]. The

FtsH gene from

Bacillus subtilis can be induced by heat and hypertonic conditions

[27], while knockout of

FtsH in this same bacterial species induces resistance to salt and is heat-stress sensitive

[28]. The expression of the

FtsH gene in wine bacteria increases under high temperature and osmotic stress and can compensate for the growth defects of

E. coli FtsH mutants under heat shock conditions

[29].

2. The Expression Pattern of CaFtsH Genes in Pepper Across Different Tissues during Development and Stress Responses

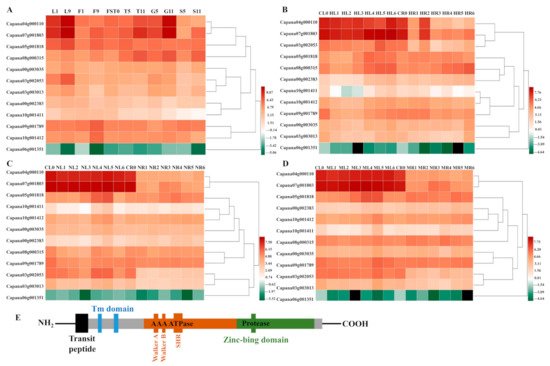

The transcription data set of the 12 CaFtsHs genes were obtained from the pepper transcriptome database, with transcription data for the CaFtsHs genes at 11 different developmental stages (including six tissues). These data were drawn into a heat map with performing hierarchical clustering (Figure 1A). The heat map profile showed that CaFtsH06, CaFtsH01 and CaFstH05 genes were significantly upregulated. Among them, the CaFtsH06 was expressed in leaves (L1, L9) and flowers (F9). CaFstH05 (S5) was clearly expressed in seeds (S5), CaFtsH01 was expressed at higher levels in fruits (FST0), while the expression of CaFstH04 was highest in seeds (S11). CaFstH09 and CaFstH10 were only expressed at higher levels in flowers (F9), and CaFstH11 also showed higher expression levels in leaves (L9). The expression levels of CaFstH02 and CaFstH08 were not high in all the tested pepper tissues. In addition, the CaFstH12 gene was almost undetectable in all the tested tissues.

Figure 1. Heat map of CaFtsHs family gene expression in pepper. (A) Dynamic heat map of the CaFtsHs family genes in different tissues and organs of pepper. L1 and L9 stand for leaves collected at 2 d and 60 d after emergence, respectively; F1 and F9 describe the smallest and largest flower buds, respectively; FST0 indicates the fruit collected at 3 days after flowering (DAF); T5 and T11 stand for placenta collected at 30 and 60 (DAF), respectively; S5 and S11 show seeds collected at 30 and 60 DAF, respectively; G5 and G11 represent peels collected at 30 and 60 DAF, respectively. (B) Expression pattern of CaFtsHs family genes in pepper under heat stress. CL0/CR0 stand for control in leaves/roots, respectively, and HL/HR stand for expression levels of CaFtsHs genes after heat stress (42 °C) in leaves/roots at 0, 0.5, 1, 3, 6, 12, and 24 h t, respectively. (C) Expression of CaFtsHs family genes in pepper under salt stress (200 mM NaCl). CL0/CR0 represent control in leaves/roots, respectively; NL/NR stand for levels of CaFtsHs genes in leaves/roots at 0, 0.5, 1, 3, 6, 12, and 24 h post-treatment, respectively. (D) Profile of CaFtsHs family genes in pepper leaf and root tissues under osmotic stress (400 mM mannitol). CL0/CR0, ML1/MR1, ML2/MR2, ML3/MR3, ML4/MR4, ML5/MR5, and ML6/MR6 show the expression levels of CaFtsHs genes in leaves/roots at 0, 0.5, 1, 3, 6, 12, and 24 h post-treatment, respectively. The date was normalized with log2 transformation. (E) The conserve motifs of CaFtsH are shown in different colors. TM (transmembrane domain), SRH (second region of homology), Zn2+ metalloprotease domain (protease), and the conserved ATPase domains of Walker A and B are marked. Two transmembrane domains (TM domain, blue) and transit peptide (black) regions are shown.

The dynamic expression patterns of

CaFtsH gene family members under different stress treatments (osmotic, heat, and salt stress) were also observed (

Figure 1B–D). The expression level of

CaFtsH06 gene in pepper leaves gradually increased after 6 h of continuous heat shock and was quite distinct at 24 h (

Figure 1B). However, the expression levels of

CaFtsH06 and

CaFtsH01 first decreased after heat treatment, slightly increased after 1 h, and again decreased rapidly in the root tissue of pepper plants. After salt stress treatment, the

CaFtsH06 gene was mainly accumulated in the leaves and its accumulation at 12 h was highest (

Figure 1C). By observing the expression characteristics of

CaFtsH homologs under 400 mM mannitol stress (osmotic stress) at different periods (0, 0.5, 1, 3, 6, 12, and 24 h), it was found that the expression of

CaFtsH06 in pepper leaves under osmotic stress was most significant at 6 h of treatment (

Figure 1D). After osmotic stress,

CaFstH01,

CaFstH02,

CaFstH05,

CaFstH06,

CaFstH09, and

CaFstH10 were upregulated in pepper leaves, while

CaFstH02,

CaFstH04,

CaFstH05,

CaFstH07,

CaFstH08,

CaFstH09, and

CaFstH10 were upregulated in the roots. Under the stress of different periods of heat, salt, and osmotic stresses, the

CaFstH06 gene had the strongest response in pepper leaves, while the

CaFstH12 gene maintained a very low expression level in both pepper leaves and root tissue. The above results indicated that

CaFtsH06 may be involved in a variety of environmental stress response processes. Moreover, most of the other genes belonging to the family were not significantly altered in terms of expression across multiple stress conditions (

Figure 1). Gene structure and function are closely related, and the homologous

LeFtsH6 and

AtFtsH6 genes were noted in other reports to have had similar stress responses

[30][31]. Therefore,

CaFtsH06 was selected as the focus for further research.

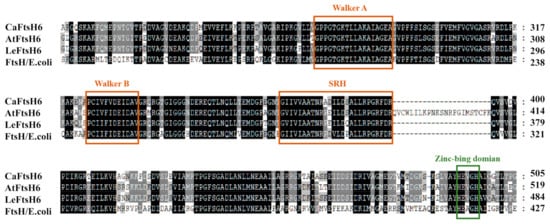

FtsH is a typical membrane-bound AAA protease family member39. The structure of FtsH protease in pepper is the same as that of other biological FtsH homologs. It is characterized by a N-terminal region with one or two transmembrane (TM) helix domains required for oligomerization and a central AAA ATPase module. Additionally, the C-terminal domain of the conserved zinc binding site (HEXXH) is required for proteolytic activity

[22]. By combining previous studies and the determination of the protein structure from a prediction website,

Figure 1E and Figure 3 provides a schematic diagram of FtsH genes, describing the hypothetical structure of FtsH protease in Arabidopsis and pepper.

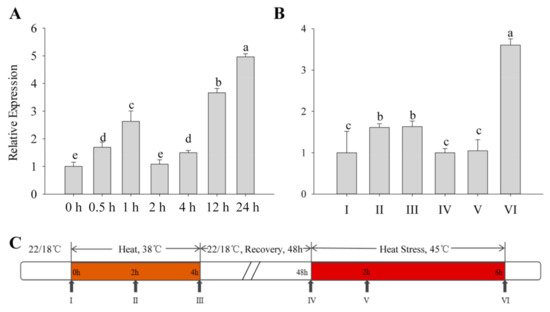

3. Expression of CaFtsH06 under Heat Stress in Pepper

All types of exogenous heat stress from the outside acts on plants, and the severity of their damage mainly depends on how fast the plant responds to the stress. The expression patterns of the CaFtsH06 gene in R9 heat-tolerant pepper lines that were exposed to different heat treatments were determined. First, the basic thermotolerance treatment of R9 was analyzed (Figure 2A). At the beginning of the treatment, the expression of CaFtsH06 in pepper increased slowly and then decreased after 2 h of treatment, but after 24 h, the expression of CaFtsH06 increased rapidly to five times the expression level that occurred after 2 h of treatment. The acquired thermotolerance treatment of R9 plants (Figure 2B) between hours 2 and 4 of the heat acclimation was also analyzed. The expression level of CaFtsH06 in leaves was not obvious and tended to be flat. In the recovery phase at 22 °C, the expression level of CaFtsH06 first appeared to decrease, with an expression level that was similar to that level before treatment. However, after the high-temperature treatment at 45 °C, the expression level of CaFtsH06 rose rapidly after treatment and reached its maximum at 6 h, and its expression level was more than 3 times that of the control plant (38 °C, 4 h), as Figure 2C shows, for high-temperature treatment and normal temperature recovery.

Figure 2. Analysis of the change in CaFtsH06 expression in pepper plants under heat stress. (A) Detection of background heat tolerance of CaFtsH06 in pepper. (B) Detection of acquired heat tolerance associated with CaFtsH06 in pepper. (C) A time course of high temperature treatment and normal temperature recovery, with the arrows indicating the time points at which pepper leaves were collected (samples I–VI). Different letters denote statistical significance (p < 0.05).

4. Structure Analysis of CaFtsH06 Proteins

Based on the close phylogenetic relationship between tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) and pepper plants, we determined that the gene should be designated as CaFtsH06 (GenBank accession number XP016580880) based on its homology to tomato metalloproteinase LeFtsH6 (NP001234191). The full-length CaFtsH06 cDNA is 2301 bp, with a 194-bp 5′ untranslated region (5′UTR), 70-bp 3′untranslated region (3′UTR), and 2037-bp ORF. The corresponding protein molecular weight is 77.54 KDa, isoelectric point is 6.29 and instability index is 31.99 (Supplementary Table S1). Multiple alignments of the deduced amino acid sequences of CaFtsH06, AtFtsH6, LeFtsH6, and FtsH/E. coli revealed a consensus region (Figure 3). The central region of the CaFtsH06 contains two putative ATP binding sites (Walker A, Walker-B) and a putative SRH (the second region) for homology. The C-terminus of the CaFtsH06 protein contains a putative zinc-binding motif HEXGH (where each X is a non-conserved amino acid residue).

Figure 3. Analysis of the characteristics of FtsH protein structures. Multiple alignments of the deduced amino acid sequences of CaFtsH06, AtFtsH6, LeFtsH6, and FtsH/E. coli, with the FtsH-specific motif shown by a rectangular box. Part of the protein sequence is drawn with a colored rectangle to match the figure in (Figure 1E).

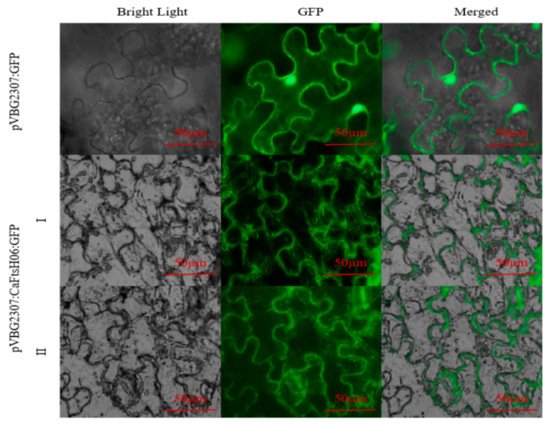

5. Subcellular Localization of CaFtsH06 Proteins

The subcellular localization of CaFtsH06 was predicted using the online tool WOLF PSORT (https://wolfpsort.hgc.jp/) (accessed on 10 August 2020), which predicted that CaFtsH06 localized mainly to the mitochondria and cell membrane. To confirm the subcellular localization of CaFtsH06 protein, the pVBG2307:GFP and pVBG2307:CaFtsH06:GFP fusion plasmids were transiently expressed in tobacco leaves. We found that the green fluorescence signal of pVBG2307:CaFtsH06:GFP was detected in the tobacco leaf mitochondria and cell membrane, while the fluorescence of pVBG2307:GFP was distributed throughout the cell, indicating that CaFtsH06 protein in pepper may play a role in the mitochondria and cell membrane (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Analysis of the characteristics of CaFtsH06 protein’s subcellular localization. The localization of pVBG2307:CaFtsH6:GFP fusion protein in tobacco cells (I-II), with pVBG2307:GFP as a control. Bright light: cells in bright field; GFP: fluorescence of GFP protein under green fluorescence; merged: overlapped image of GFP and bright light. Bar = 50 μm.

6. Knockdown of CaFtsH06 Decreased Abiotic Stress Tolerance in Pepper

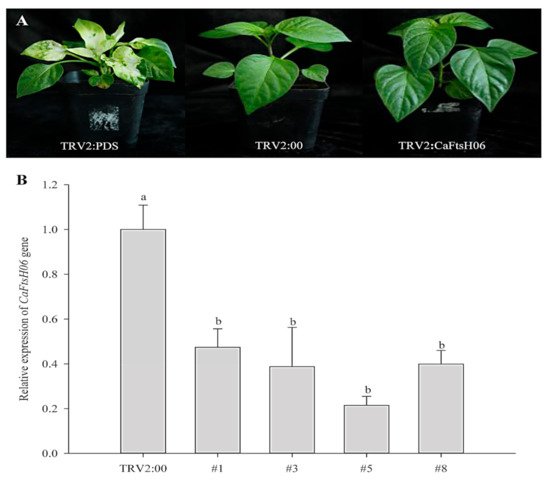

The silencing vector TRV2: CaFtsH06 was constructed in the Agrobacterium GV3101 to create CaFtsH06-silenced plants. The leaves of TRV2:CaPDS (positive control) pepper seedlings showed photobleaching symptoms, but no obvious difference in phenotype was observed between TRV2:CaFtsH06 and the negative control TRV2:00 pepper lines under normal growth conditions (Figure 5A). The silencing efficiency of CaFtsH06 in silenced pepper lines exceeded 60% (Figure 5B). Thus, the control plants (TRV2:00) and CaFtsH06-silenced plants (TRV2:CaFtsH06) were used for the subsequent experiment.

Figure 5. The phenotypes and silencing efficiency of CaFtsH06 in pepper leaves. (A) The phenotypes of TRV2:CaPDS positive control plants, TRV2:00 negative control plants, and pTRV2:CaFtsH06-silenced plants are shown, respectively. (B) Silencing efficiency of CaFtsH06 in pepper. Different letters denote statistical significance (p < 0.05).

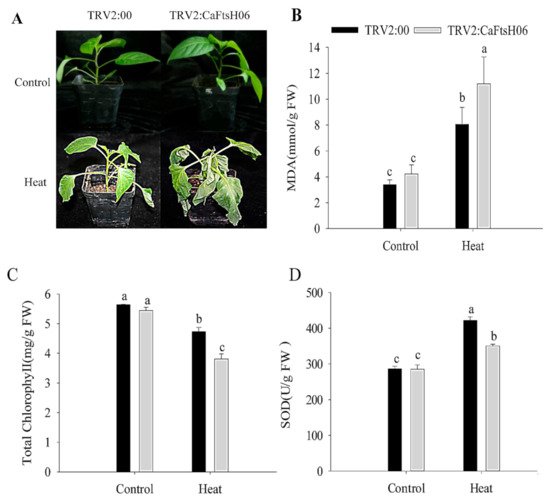

The CaFtsH06-silenced and control R9 pepper plants were exposed to 45 °C for 24 h, and significant differences in their phenotypes were observed after high temperature treatment. The leaves of the silenced plants showed severe wilting and drooping, while control plants only exhibited slightly curled edges of leaves (Figure 6A). At the same time, it was determined that the malondialdehyde (MDA) content of the silenced and control plants increased after heat stress, but this increase in the MDA content of the silenced plants was significantly higher than that in control plants (Figure 6B). Similarly, the chlorophyll content of both silenced and control plants decreased after heat shock, but this decrease in the chlorophyll content of the silenced plants was significantly lower than that in control plants (Figure 6C). After the heat stress stimulation, the SOD content of the control and silenced plants was increased, but the increase in the SOD content of the silenced plants were lower than that of the control plants (Figure 6D). The analysis of the above results showed that silencing of the CaFtsH06 gene in pepper reduces its ability to respond to heat shock.

Figure 6. Analysis of heat tolerance of CaFtsH06-silenced pepper. (A) Phenotype identification of pTRV2:00 and pTRV2:CaFtsH06-silenced plants after heat treatment. (B) The malondialdehyde (MDA) content of plants after heat stress. (C) Total chlorophyll content of plants after heat stress. (D) The SOD content of plants after heat stress. Different letters denote statistical significance (p < 0.05).

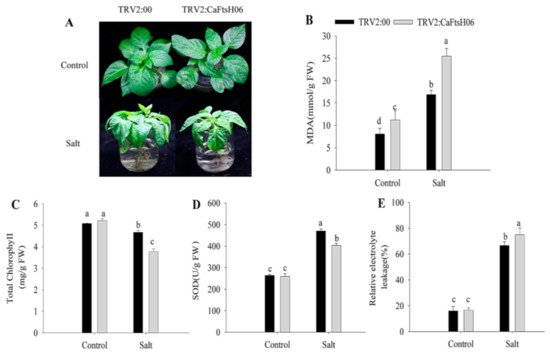

To further explore the function of CaFtsH06 in saline conditions, the CaFtsH06-knockdown and control pepper seedlings were immersed in a 300 mM NaCl solution for 24 h. The leaves of the CaFtsH06-silenced plants showed severe wilting and shrinkage, with the lower leaves having fallen off, while the leaves of the control plants only showed signs of wilting (Figure 7A). At the same time, the MDA content and REL of the two plant types increased significantly, but the increase in the silenced plants was statistically more than that in the non-silenced pepper plants (Figure 7B,E). Additionally, the chlorophyll content of the CaFtsH06-silenced and control plants decreased, but this decrease was significantly lower in the silenced plants than in the control plants (Figure 7C). The SOD content of the control and silenced plants increased after salts stress, but this increase in the SOD content of the control plants was significantly higher than that in the silenced plants (Figure 7D).

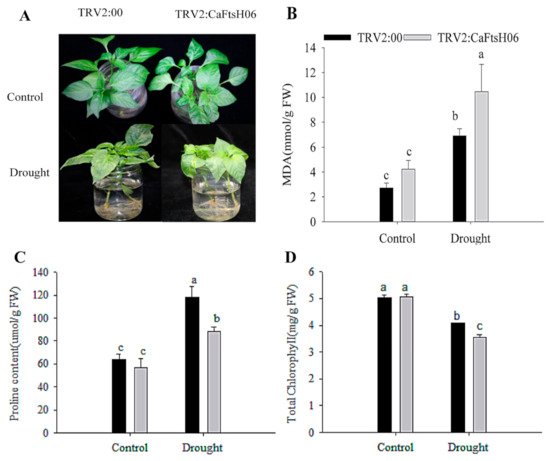

Figure 7. Salt stress tolerance analysis in silenced pepper. (A) Phenotypes of pTRV2:00 and pTRV2:CaFtsH06-silenced plants after salt stress. (B) The MDA content of plants after salt stress. (C) Total chlorophyll content of plants after salt stress. (D) The SOD content of plants after salt stress. (E) The relative electrolyte leakage of plants after salt stress. Different letters denote statistical significance (p < 0.05). For the osmotic tolerance analysis of silent and control plants, the roots of the plant samples were cleaned first and then completely immersed in a 300 mM mannitol solution. The silent and control plants were then subjected to 36 h of drought treatment, and the leaves of CaFtsH06-silenced plants were observed to exhibited lost water tension, sagging and shrinking, while the control plants did not change significantly (Figure 8A).

Figure 8. Analysis of osmotic tolerance of CaFtsH06-silenced pepper. (A) Phenotype identification of pTRV2:00 and pTRV2:CaFtsH6 plants after osmotic stress. (B) The MDA content of plants after osmotic stress. (C) The proline content of plants after osmotic stress. (D) Total chlorophyll content of plants after osmotic stress. Different letters denote statistical significance (p < 0.05).

After treatment, the MDA content of the CaFtsH06-silenced plants increased significantly, more than that of the control plants (Figure 8B). Plant leaves initiate stress responses to external stimuli and rapidly accumulate proline, but the accumulation of proline in the CaFtsH06-silenced plant leaves was not increased (Figure 8C). Similarly, the chlorophyll content of the CaFtsH06-silenced plants was significantly reduced as compared to the control plants (Figure 8D). Thus, it was preliminarily determined that silencing the CaFtsH06 gene in pepper reduces osmotic tolerance in pepper.

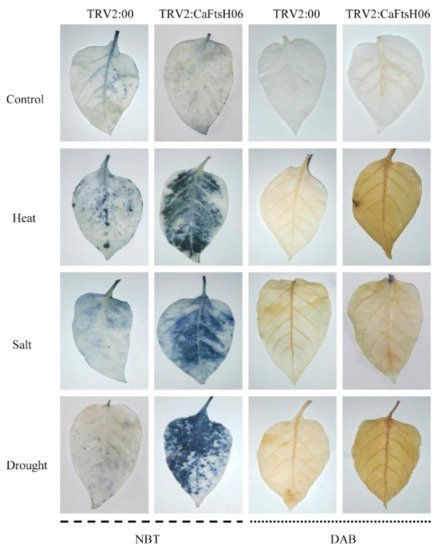

Osmotic stress can lead to the disordering of ion distribution and balance in plants, the deposition of large amounts of destructive ROS substances, and damage to the internal structures and the function of cells. Thus, it was important to explore the influence of CaFtsH06 silencing on the accumulation and removal of ROS in the pepper R9 lines. Accordingly, we used histochemical staining DAB and NBT methods to measure the changes in H2O2 and ·O2−, respectively.

As shown in Figure 9, the DAB deposition area of the CaFtsH06-silenced and control plants was higher after stressed conditions as compared to the unstressed plants, but the stained areas of the CaFtsH06-silenced plants were significantly larger than those of the control plants. Similarly, after coercion treatment, the NBT deposition areas of silenced and control peppers were significantly larger than those of unstressed plants, while the stained areas of CaFtsH06-silenced plants were significantly larger than those of control plants. These results indicate that as compared to the leaves of control plants, the leaves of CaFtsH06-silenced plants had higher levels of H2O2 and ·O2−. Thus, when the CaFtsH06 gene was silenced in pepper, the ability of the plants to remove harmful substances such as peroxides was also reduced, such that the ability of pepper to resist stress was greatly reduced.

Figure 9. Histochemical staining of pepper leaves under heat, salt, and osmotic stresses in the CaFtsH06-silenced and control pepper plants. The NBT and DAB staining in CaFtsH06-silenced plant leaves after heat, salt, and drought stress treatments revealed darker stanning patterns than the control plants, indicating the accumulation of ·O2− and H2O2, respectively.