Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Javier del Campo | + 859 word(s) | 859 | 2021-06-16 08:27:00 | | | |

| 2 | Vicky Zhou | Meta information modification | 859 | 2021-06-24 03:15:12 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Del Campo, J. Smartphone-Enabled Personalized Diagnostics. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/11173 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Del Campo J. Smartphone-Enabled Personalized Diagnostics. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/11173. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Del Campo, Javier. "Smartphone-Enabled Personalized Diagnostics" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/11173 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Del Campo, J. (2021, June 23). Smartphone-Enabled Personalized Diagnostics. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/11173

Del Campo, Javier. "Smartphone-Enabled Personalized Diagnostics." Encyclopedia. Web. 23 June, 2021.

Copy Citation

Smartphones are increasingly versatile thanks to the wide variety of sensor and actuator systems packed in them. Mobile devices today go well beyond their original purpose as communication devices, and this enables important new applications, ranging from augmented reality to the Internet of Things. Personalized diagnostics is one of the areas where mobile devices can have the greatest impact.

point of care devices

smarthphone-based diagnostics

molecular methods

biosensors

1. Introduction

Today, mobile phone capabilities include 3G to 5G, WiFi, Bluetooth, and near field communication (NFC). When mobile phones were first employed in POC settings in the early 2000s, users could only take advantage of their data transmission capabilities. They were, thus, initially used to replace personal digital assistants (PDAs) and facilitate communication between medical staff [1]. Mobile phone cameras began to be exploited shortly after, and one of their earliest uses was to capture screenshots from ultrasound images for sharing among professionals [2]. Shortly afterwards, Whitesides et al. reported one of the first uses of a mobile phone camera to capture images from a paper-based assay and send them elsewhere for analysis [3]. Since then, the use of phone cameras has become widespread, and nearly all works reporting the use of mobile-phone-based diagnostic systems rely on image capture and analysis, as highlighted in recent reviews [4][5][6][7]. Mobile phone cameras have enabled colourimetric methods [8] and more advanced and sensitive techniques such as fluorescence [9] and electrogenerated chemiluminescence (ECL) [10]. Alternatively, the ambient light sensor (ALS) present in smartphones can also be used to develop simple optical sensors in tandem with light-emitting detection methods [11]. However, an important limitation of image-based systems is that they require bulky accessories to ensure controlled lighting or darkness and an adequate focal distance [12]. The silver lining is that some of the colourimetric tests available today will still render quantitative information if placed in direct contact with either the camera or the ALS, as already suggested by Hogan et al. [13].

Electrochemical detection methods, which are complementary to the aforementioned optical methods, can also be applied by mobile phones. Although working electrode potential control is difficult in solid-state devices, stable printed reference electrodes have been reported, showing that high-performance, inexpensive, and disposable devices can be produced [14]. Miniature potentiostats that can be connected to the mobile phone USB/charger port have been developed as well [15][16][17]. The audio jack has also been used to deliver power to an electrochemical cell. Although, in this case, potential control is restricted to potential steps, smartphones have been successfully used to drive an ECL-based detection system [10][13]. These works illustrate the feasibility of spectroelectrochemical analysis [18] using smartphones by coupling electrochemical actuation and optical detection. However, it can be anticipated that as mobile technologies evolve and audio jacks and charge connector ports disappear, electrochemical systems will remain very much alive [19][20].

2. Next Steps for Smartphone Full-Capacity Exploitation in Personal Diagnostic Systems

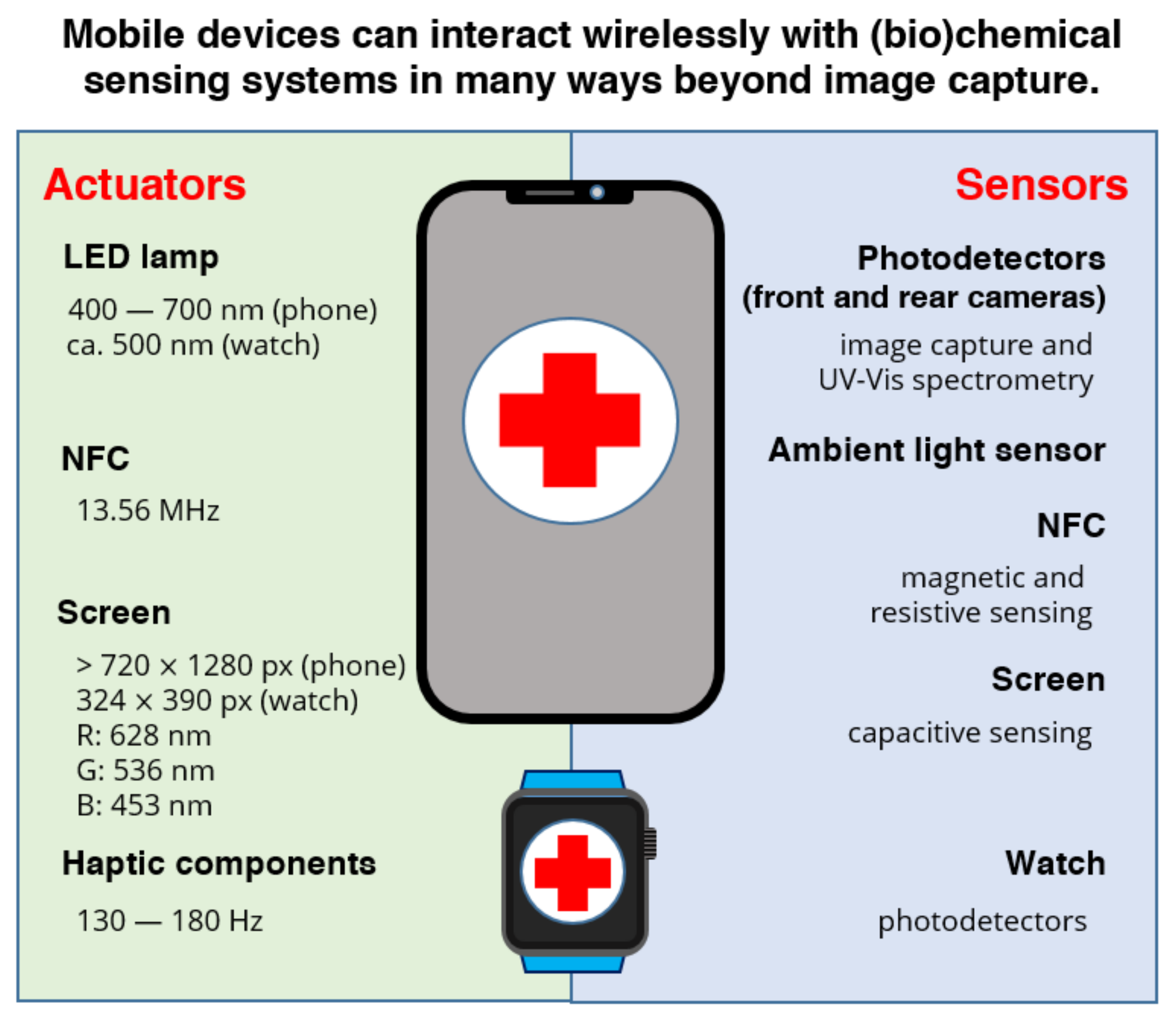

Besides image acquisition and data transmission, current smartphones display a variety of functions and capacities that can or could be helpful for the production of POC diagnostic devices, as represented in Figure 1. For instance, mobile phone devices can transfer energy wirelessly in three different ways, using radiofrequency (RF), light, and motion (vibration). RF is one of the easiest and most efficient ways to interact with the disposable component of the diagnostic device, as reflected by the increasing volume of publications reporting NFC-powered POC devices. The flashlight and the screen can be useful light sources too, and their use has been occasionally described. In contrast, haptic feedback systems responsible for providing a tactile response to certain user inputs, i.e., vibration, have received virtually no attention from the lab-on-a-chip community until now. This is despite the fact that they could facilitate reagent mixing in a smartphone-based POC or lab-on-a-chip device, for instance, by facilitating the dissolution of dry reagents in microchannels and microchambers upon wetting with capillary laminar flow.

Figure 1. Summary of the main actuation and detection modes currently available in smart personal devices.

Figure 1. Summary of the main actuation and detection modes currently available in smart personal devices.3. Conclusions and Outlook

Following the worldwide sanitary crisis of 2020, the need to develop population-wide testing strategies and tools has become clear and is more pressing than ever. Mobile devices are ubiquitous and have the potential to become truly personal analytical platforms in the near future. This is thanks to their powerful analog, digital, and telecommunication functions combined with cloud data processing. The new systems will combine the high-performance of advanced molecular diagnostics with the affordability of current lateral flow devices and will fulfill the ASSURED criteria more closely.

Here, we have shown examples of how mobile devices can be used beyond image analysis and data transmission to enable personalized diagnostic platforms that can reach a wider population base. Mobile devices can transfer different forms of wireless energy (radiofrequency, light, and even motion) to disposable sensing devices that are able to process a sample and return vital analytical information to the mobile device for further processing.

We believe that this vision is possible because both the technology and much of the required knowledge already exist. However, the development of disposable platforms integrating functionality beyond current lateral flow tests presents important challenges for both materials science and manufacturing, as the environmental impact and sustainability of the new platforms must also be considered.

References

- Kim, H.-S.; Kim, N.-C.; Ahn, S.-H. Impact of a nurse short message service intervention for patients with diabetes. J. Nurs. Care Qual. 2006, 21, 266–271.

- Blaivas, M.; Lyon, M.; Duggal, S. Ultrasound image transmission via camera phones for overreading. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2005, 23, 433–438.

- Martinez, A.W.; Phillips, S.T.; Carrilho, E.; Thomas, S.W.; Sindi, H.; Whitesides, G.M. Simple Telemedicine for Developing Regions: Camera Phones and Paper-Based Microfluidic Devices for Real-Time, Off-Site Diagnosis. Anal. Chem. 2008, 80, 3699–3707.

- Quesada-González, D.; Merkoçi, A. Mobile phone-based biosensing: An emerging “diagnostic and communication” technology. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017, 92, 549–562.

- Rezazadeh, M.; Seidi, S.; Lid, M.; Pedersen-Bjergaard, S.; Yamini, Y. The modern role of smartphones in analytical chemistry. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2019, 118, 548–555.

- Kassal, P.; Steinberg, M.D.; Steinberg, I.M. Wireless chemical sensors and biosensors: A review. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2018, 266, 228–245.

- Banik, S.; Melanthota, S.K.; Arbaaz; Vaz, J.M.; Kadambalithaya, V.M.; Hussain, I.; Dutta, S.; Mazumder, N. Recent trends in smartphone-based detection for biomedical applications: A review. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2021, 413, 2389–2406.

- Lee, D.S.; Jeon, B.G.; Ihm, C.; Park, J.K.; Jung, M.Y. A simple and smart telemedicine device for developing regions: A pocket-sized colorimetric reader. Lab Chip 2011, 11, 120–126.

- Breslauer, D.N.; Maamari, R.N.; Switz, N.A.; Lam, W.A.; Fletcher, D.A. Mobile phone based clinical microscopy for global health applications. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, 1–7.

- Delaney, J.L.; Doeven, E.H.; Harsant, A.J.; Hogan, C.F. Use of a mobile phone for potentiostatic control with low cost paper-based microfluidic sensors. Anal. Chim. Acta 2013, 803, 123–127.

- Dutta, S. Point of care sensing and biosensing using ambient light sensor of smartphone: Critical review. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2019, 110, 393–400.

- Chen, W.; Yao, Y.; Chen, T.; Shen, W.; Tang, S.; Lee, H.K. Application of smartphone-based spectroscopy to biosample analysis: A review. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2021, 172, 112788.

- Doeven, E.H.; Barbante, G.J.; Harsant, A.J.; Donnelly, P.S.; Connell, T.U.; Hogan, C.F.; Francis, P.S. Mobile phone-based electrochemiluminescence sensing exploiting the ‘USB On-The-Go’ protocol. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2015, 216, 608–613.

- Moya, A.; Pol, R.; Martínez-Cuadrado, A.; Villa, R.; Gabriel, G.; Baeza, M. Stable Full-Inkjet-Printed Solid-State Ag/AgCl Reference Electrode. Anal. Chem. 2019, 91.

- Nemiroski, A.; Christodouleas, D.C.; Hennek, J.W.; Kumar, A.A.; Maxwell, E.J.; Fernández-Abedul, M.T.; Whitesides, G.M. Universal mobile electrochemical detector designed for use in resource-limited applications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 11984–11989.

- Guo, J. Smartphone-Powered Electrochemical Biosensing Dongle for Emerging Medical IoTs Application. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2018, 14, 2592–2597.

- Li, J.; Lillehoj, P.B. Microfluidic Magneto Immunosensor for Rapid, High Sensitivity Measurements of SARS-CoV-2 Nucleocapsid Protein in Serum. ACS Sens. 2021.

- Garoz-Ruiz, J.; Perales-Rondon, J.V.; Heras, A.; Colina, A. Spectroelectrochemical Sensing: Current Trends and Challenges. Electroanalysis 2019, 31, 1254–1278.

- Ainla, A.; Mousavi, M.P.S.; Tsaloglou, M.N.; Redston, J.; Bell, J.G.; Fernández-Abedul, M.T.; Whitesides, G.M. Open-Source Potentiostat for Wireless Electrochemical Detection with Smartphones. Anal. Chem. 2018, 90, 6240–6246.

- Teengam, P.; Siangproh, W.; Tontisirin, S.; Jiraseree-amornkun, A.; Chuaypen, N.; Tangkijvanich, P.; Henry, C.S.; Ngamrojanavanich, N.; Chailapakul, O. NFC-enabling smartphone-based portable amperometric immunosensor for hepatitis B virus detection. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2021, 326, 128825.

More

Information

Subjects:

Medical Informatics; Engineering, Biomedical

Contributor

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.2K

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

24 Jun 2021

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No