The valorization of waste organic materials following a holistic approach in line with the bioenergy concept is explained in this post.

- stabilization

- waste-derived fertilizer

- organic matter

- synergy

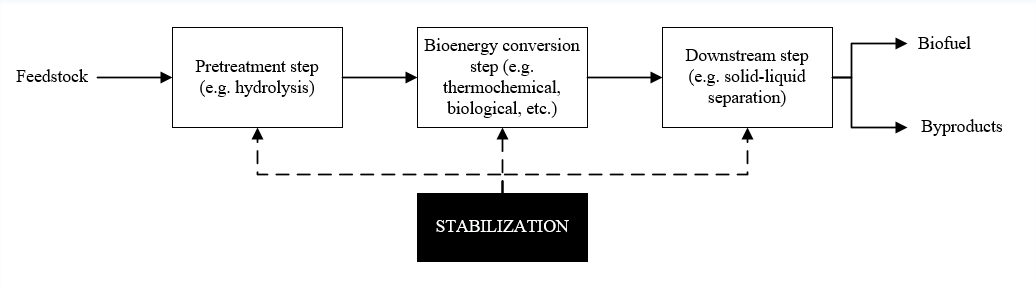

The stabilization ensures that all elements (carbon, nitrogen, sulphur, etc.) of the biomass are used efficiently in the bioenergy process (Figure 1). For instance, if the bioenergy conversion step involves microbial activity (e.g. biogas production, bioethanol production, etc.), the stabilization leads to greater yields and better quality of fuel, by providing the microbes with the best conditions (e.g. availability of carbon and nutrients) to carry out their work. However, the stabilization does not necessarily need to be applied in the pretreatment step or in the bioenergy conversion step (Figure 1). In fact, the stabilization can be also applied as part of the downstream step to the residues of the bioenergy process (e.g. anaerobic digestate, biochar, ect.) [1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8]. The better quality of biofuel and byproducts implies the minimization of the pollution during the handling of these materials.

Figure 1 – Potential action points of stabilisation in a bioenergy process

It should be noted that the term stability is used in the literature for several purposes. This post explains what the term stability means for organic wastes or biomass, in relation to the microbial activity as per your request. First of all, even for this particular scenario, the term stability is confusing as sometimes appears in the literature interchangeably with the term maturity (Saveyn and Eder, 2014). For this reason, during my PhD I needed to establish some definitions, after doing an exhaustive review of the relevant literature (including both scientific papers and regulations). These definitions also help me to explain the portfolio managers what is the stabilisation in relation to the microbial activity.

The stability accounts the fate of carbon (Figure 2) while the maturity accounts the fate of all other elements, during the fermentation of the feedstock that take place in the bioenergy conversion step (Figure 1) and after the land application of the byproducts (Figure 4). Another reason for differentiating between carbon and all the other elements is that organic carbon is only nutrient for the microbes but not for plants. As nitrogen is the most common heteroatom in the waste biomass, the content of ammoniacal nitrogen (NH4+-N) could be a measurement of maturity (Alburquerque et al., 2012; Astals et al., 2013; Bernal et al., 2009). The regulations only establish threshold values of stability to achieve the end-of-waste status and allow the application to land of a residue. For example, in the UK, the measurement of the (biological) stability of the anaerobic digestate is done with a biochemical methane potential (BMP) test while the stability of the compost is determined by measuring the carbon dioxide released (British Standards Institution, 2011). For animal manure and slurry, there is no measurement and what limits the direct use of these residues is the compulsory storage period of 6 months (UK government, 2016). The rationale of these regulations is to minimise the emissions of greenhouse gases (e.g. CH4, CO2, etc.) after land application. I propose to use the Carbon Use Efficiency (CUE) as a measurement of the stability (Figure 2). This implies to establish a lower limit for the carbon assimilated by microbes rather than an upper limit for the carbon mineralised (i.e. lost by microbial respiration).

Figure 2 – Proposed parameters to measure the stability and maturity of a byproduct of the bioenergy process (Figure 1). I have deleted some of the content to make the definitions more vague and applicable to all bioenergy processes.

As can be seen in the Figure 3, which shows a BMP test, the release of biogas due to microbial respiration is dependent on the composition of the organic amendment. Traditionally, the composition of organic amendment has been expressed as the carbon-to-nitrogen ratio (C/N) although other nutrients also affect the utilisation of the carbon by microbes (Menon et al., 2017). The biogas release is also dependent on the substrate-to-inoculum ratio (S/I), which in a continuous bioreactor is expressed as organic loading rate (OLR). The highest CUE, and therefore the highest stability of the organic amendment, were obtained at the lowest C/N (Figure 3), because the microbes have all the nutrients that they need to build their cell structures and they do not need to get rid of the excess of carbon. Similarly, with lower amounts of organic waste, the microbes would be in starvation mode processing more efficiently the carbon for their growth, compared to higher OLRs in which more carbon is lost in microbial respiration due to the excessive microbial activity. Since less carbon ends up in the microbial biomass, which is measured as part of the volatile solids (VS), the CUE decreases.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/su14053127

References

- Alejandro Moure Abelenda; Kirk T. Semple; Alfonso Jose Lag-Brotons; Ben M. J. Herbert; George Aggidis; Farid Aiouache; Effects of Wood Ash-Based Alkaline Treatment on Nitrogen, Carbon, and Phosphorus Availability in Food Waste and Agro-Industrial Waste Digestates. Waste and Biomass Valorization 2020, 12, 3355-3370, 10.1007/s12649-020-01211-1.

- Alejandro Moure Abelenda; Kirk T. Semple; Alfonso Jose Lag-Brotons; Ben M.J. Herbert; George Aggidis; Farid Aiouache; Impact of sulphuric, hydrochloric, nitric, and lactic acids in the preparation of a blend of agro-industrial digestate and wood ash to produce a novel fertiliser. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2020, 9, 105021, 10.1016/j.jece.2020.105021.

- Alejandro Moure Abelenda; Kirk T. Semple; Alfonso Jose Lag-Brotons; Ben M.J. Herbert; George Aggidis; Farid Aiouache; Kinetic study of the stabilization of an agro-industrial digestate by adding wood fly ash. Chemical Engineering Journal Advances 2021, 7, 100127, 10.1016/j.ceja.2021.100127.

- Alejandro Moure Abelenda; Kirk T Semple; Alfonso Jose Lag-Brotons; Ben Mj Herbert; George Aggidis; Farid Aiouache; Alkaline Wood Ash, Turbulence, and Traps with Excess of Sulfuric Acid Do Not Strip Completely the Ammonia off an Agro-waste Digestate. Edelweiss Chemical Science Journal 2021, 4, 19-24, 10.33805/2641-7383.127.

- Alejandro Moure Abelenda; Farid Aiouache; Wood Ash Based Treatment of Anaerobic Digestate: State-of-the-Art and Possibilities. Processes 2022, 10, 147, 10.3390/pr10010147.

- Alejandro Moure Abelenda; Chiemela Victor Amaechi; Manufacturing of a Granular Fertilizer Based on Organic Slurry and Hardening Agent. Inventions 2022, 7, 26, 10.3390/inventions7010026.

- Alejandro Moure Abelenda; Kirk T. Semple; Alfonso Jose Lag-Brotons; Ben M.J. Herbert; George Aggidis; Farid Aiouache; Strategies for the production of a stable blended fertilizer of anaerobic digestates and wood ashes. Nature-Based Solutions 2022, n/a, 100014, 10.1016/j.nbsj.2022.100014.

- Alejandro Moure Abelenda; Kirk T. Semple; George Aggidis; Farid Aiouache; Circularity of Bioenergy Residues: Acidification of Anaerobic Digestate Prior to Addition of Wood Ash. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3127, 10.3390/su14053127.