The term ETI Myth refers to the belief that extraterrestrial intelligent beings exist and, further, ETI are more advanced than earthlings in evolution, scientific knowledge, technological progress, and moral achievement. Further, according to the myth, ETI have evolved beyond religion and now live in a civilization defined by its science and technology. No empirical evidence supports such an imaginative conceptual set, yet this myth propels and inspires many SETI researchers and other astrobiologists looking for extraterrestrial intelligence. The ETI myth deserves careful dissection and diagnosis. The ETI myth deserves demythologizing if not demythicizing.

- Astrobiology

- Astrotheology

- SETI

- ETI Myth

- Myth

- Evolution

- Demythologizing

- Science and Religion

- Drake Equation

- Extraterrestrial Intelligence

1. Introduction

The term ETI Myth refers to the belief that extraterrestrial intelligent beings exist and, further, they are more advanced than earthlings in evolution, scientific knowledge, and technological progress. Sometimes the myth includes still more: it includes trust in the evolutionary advance of intelligence expressed through science, hinting that more highly evolved ETI could bring scientific salvation to planet earth. Here is the myth as articulated by physicist and astrobiologist Paul Davies.

Indeed, it [an extraterrestrial civilization] might have achieved our level of science and technology millions or billions of years ago….it is more likely that any civilization that had surpassed us scientifically would have improved on our level of moral development, too. One may even speculate that an advanced alien society would sooner or later find some way to genetically eliminate evil behavior, resulting in a race of saintly beings.[1]

This belief that aliens could eliminate evil behavior defies both empirical evidence and common wisdom. Yet the idea of a scientifically and morally advanced extraterrestrial civilization is such a potent conceptual set that it orients and inspires some of the most serious research along with our culture's interpretation of space phenomena.

The employment of this particular set of assumptions in itself should not be eschewed from the space sciences, to be sure. But when such assumptions begin to take on the structure of a worldview and elicit a passionate hope for a scientific savior, we then enter the domain of myth. In this case, the science becomes a surrogate religion, a replacement for traditional religion. The astrotheologian needs to discriminate between science and myth--to demythologize if not demythicize--in order to pursue a strictly rational response to the prospect of ETI.[2]

It's not unusual for a scientist to define myth as an untrue story. "Myths.are not true of the world."[3] Yet, curiously, at least one myth has an address right in the scientific downtown, namely, the ETI myth.[4]

The ETI myth appears in two communities: among astrobiologists and among UFO aficionados. Both groups share this single myth, a single worldview. When we turn to traditional religious believers, the ETI myth surfaces as well but with less detailed articulation or commitment. In what follows, our attention will be given to the ETI myth among astrobiologists.[5]

2. The Demise-of-Religion-Prophecy

Curiously, one plank in the ETI myth platform is a prediction. Here is what ETI myth believers predict: when we terrestrials first make contact with extraterrestrials who are more highly evolved and more technologically advanced than we earthlings, then the world's great religions will face a crisis of belief and collapse. This demise-of-religion-prophecy within the ETI myth is an assumption, a dramatic assumption. But, when examined empirically, this assumption becomes quickly falsified. Data to demonstrate this falsification will be provided below in this entry.

3. Contact Optimism vs. Unique Earthism

Evolutionary theory does not support the ETI myth, even though believers in the myth presuppose that evolutionary theory is its friend. How does this work? Here's how. Believers in the ETI myth smuggle progress into their version of evolution.[6]

Debate over how evolution should be interpreted provides the background to a persisting squabble between contact optimism, on the one hand, and the unique earth view, on the other. The unique earthers hold that evolution taking place on an exoplanet could not, statistically speaking, duplicate what has happened on earth. Unique earthers try to throw a wet blanket on the enthusiasm of the contact optimists.

Contact Optimists contend that simple reasoning would suggest that the universe should be teeming with life. "The universe is awash with life,” declares Christian de Duve, Nobel Prize winning biologist.[7] Those holding the Uniqueness Hypothesis, in contrast, suggest that the earth is probably the first and only home for a technological civilization. Unique earthers speculate that microbial life might have emerged from abiotic chemistry in many off-Earth locations, to be sure; but certainly not intelligent life. The latter conclusion is due to the lack of an entelechy or progressive telos within the evolutionary process. Until recently, the lack of empirical evidence for the existence of extraterrestrial life combined with the high improbability of a repeat of earth’s evolutionary history seemed to give the edge to the uniqueness hypothesis, to the unique earthers.[8]

3.1 Progress versus Chance

Let's look at this in a bit more detail. The unique earth hypothesis depends on the assumption of the improbability that just the right prebiotic contingencies (chance, randomness) would fall into place to make the spring from non-life to life possible. And even if life gets started, there remains the low probability that the contingencies that made the evolution of intelligent life on earth could be repeated in sequence. “In conflict with the thinking of those who see a straight line from the origin of life to intelligent man,” writes Ernst Mayr, “I have shown that at each level of this pathway there were scores, if not hundreds, of branching points and separately evolving phyletic lines, with only a single one in each case forming the ancestral lineage that ultimately gave rise to Man.”[9] Each branch of evolutionary change is contingent, due to chance and not design. No principle of progress from simple life forms to intelligence is built into evolution. No progressive teleology. “An evolutionist is impressed by the incredible improbability of intelligent life ever to have evolved, even on earth,” adds Mayr.[10]

Philosopher of Biology Michael Ruse bluntly contradicts the contact optimist assumption that evolution inevitably leads to progress in intelligence. “There is absolutely no guarantee of an upward progression on our hypothetical planet to intelligent life forms.evolution of intelligence is not a necessary consequence of life appearing: not at all.”[11] In sum, even if a second genesis of life were to occur on an extrasolar planet, the probability that it would progress into a form that mimics intelligence on earth is virtually nil.

Contact optimists, in their defense, do not necessarily embrace the “straight line” from life’s origin to intelligence that Mayr or Ruse object to. SETI founders Carl Sagan and Frank Drake, for example, acknowledge that evolutionary contingencies do not guarantee in all cases that intelligence will develop according to a straight line from simple to complex. Rather than a straight line, they propose a variant line that might get us to a parallel stage. “There might be a kind of biological law decreeing that there are many paths to intelligence and high technology, and that every inhabited planet, if it is given enough time and it does not destroy itself, will arrive at a similar result. The biology on other planets is of course expected to be different from our own because of the statistical nature of the evolutionary process and the adaptability of life. The science and engineering, however, may be quite similar to ours, because any civilization engaged in interstellar radio communication, no matter where exists, must contend with the same laws of physics, astronomy and radio technology that we do.[12]

Note that "there might be a biological law" is a speculation; this law is not the product of empirical research. So, with this possible biological law in mind, the contact optimist predicts that many civilizations may have followed a different line than earth's while still passing through earth's present stage to much more advanced state.

3.2 Improbability versus Big Numbers

Neither the straight line nor the variant line to intelligence that leads over time to science and technology will fit with our understanding of biological evolution, argue numerous prominent evolutionary biologists. Stephen Jay Gould and Francisco J. Ayala, for example, have argued independently that if you replay earth’s evolutionary tape again and again, it will never produce the same result.[13] What we know as human intelligence is so improbable elsewhere that it must be unique to our earth, they conclude. “The chemical origin of life seemed to depend on such an improbable sequence of events, similar to throwing a die over and over and getting a six every time, that biologists were inclined to think that life elsewhere must be a very rare occurrence,” comments David Darling.[14]

Contact optimists, while recognizing the improbability problem, counter with the idea of big numbers. Because the number of possible locations in this vast universe for evolution to get started is so large, the number of possible repeats of earth’s biological history is also large. In contrast to the unique earth biologists, contact optimism has grown among astronomers. “Most of the speculation about life in the universe came from astronomers, who were generally positive about the idea simply because they thought there were probably so many planets around. With billions of potential homes, surely life couldn’t be that scarce,” comments Darling.[15] He concludes, “Almost beyond doubt, life exists elsewhere.”[16]

Big numbers are mental constructs, not empirical evidence. Yet, big numbers are persuasive.

3.3 The Drake Equation

Contact optimists, like any of us, can speculate. And speculate they do. Today’s star searchers can rely on a dramatic form of speculation known as the Drake equation. The Drake Equation, first formulated by Frank Drake in 1961 (National Radio Astronomy Observatory in Green Bank, West Virginia), looks like this: N=N*fp ne fl fi fc fL.[17]

N is the number of civilizations in the Milky Way Galaxy whose electromagnetic emissions are detectable

R* is the rate of formation of stars suitable for the development of intelligent life

fp is the fraction of those stars forming that have planetary systems

ne is the number of planets per solar system with an environment suitable for life

fl is the fraction of suitable planets on which life actually appears

fi is the fraction of life-bearing planets on which intelligent life emerges

fc is the fraction of intelligent civilizations that develop a technology that releases detectable signs of their existence. into space

L is the length of time such civilizations send detectable signs.

Hayden Observatory director Neil DeGrasse Tyson plugs in some numbers such as 300 billion galaxies in the Milky Way. He offers 0.006 for ne as the number of planets per solar system with an environment suitable for life. Finally, Tyson arrives at "up to a hundred civilizations in the galaxy communicating with radio waves now" and "possibly up to 5 billion extragalactic, radio-broadcasting civilizations.[18]

The academic value of the Drake equation is not in knowing the numerical equivalent of N. Rather, the value is that here we have a template for structuring research and filtering incoming data. As research advances, new numbers can be plugged in. The calculations will change as new information is gathered. As of the present moment, NASA estimates that 1021 planets exist in the universe, of which 1010 might be earthlike.[19] George Coyne, former director of the Vatican Observatory, estimates that there are 1017 earthlike planets in the universe.[20] Christian de Duve speculates that “the figure of about one million ‘habitable’ planets per galaxy is considered not unreasonable."[21]Astrophysicist and student of UFOs Jeffrey Bennett offers an estimate of "100 billion habitable planets in our galaxy" supporting at least "100,000 civilizations."[22] The mere appeal to such big numbers persuades many astrobiologists that contact optimism is justified.

We must grant that the Drake Equation including estimates of the number of habitable planets elsewhere in space belongs to fertile scientific research. Frank Drake should be applauded. Does this collecting big numbers in itself count as mythical? No, of course not. The mythical component gains traction in what happens next. Here are the steps from disciplined science to myth. Step one: insert progress into evolution. Step two: aver that civilizations with a longer time for evolution have advanced in intelligence, science, and technology. Step three: aver that advances in science and technology lead to advances in morality that put an end to conflict and war. Step four: prophesy that when scientifically and morally more advanced ETI contact us on earth that earth’s many religions will face a crisis of belief and collapse. Step five: prophesy science alone will thereafter reign on a peaceful planet earth. In brief, the ETI myth asks extraterrestrial science to deliver terrestrial salvation. This conceptual set looks more like myth than science, like a scientized gnostic redeemer myth.[23]

The redemptive if not salvific quality of alien intelligence takes shape in what Sagan and Drake say: contact with extraterrestrials “would inevitably enrich mankind beyond imagination.”[24]

Drake dreams further about this extraterrestrial enrichment. “Everything we know says there are other civilizations out there to be found. The discovery of such civilizations would enrich our civilization with valuable information about science, technology, and sociology. This information could directly improve our abilities to conserve and to deal with sociological problems—poverty for example. Cheap energy is another potential benefit of discovery, as are advancements in medicine.”[25] Note how this optimism extends well beyond mere contact with ETI. It includes optimism regarding the solution to “sociological” problems such as poverty and energy while giving us a leap forward in medicine. Why not eliminate war right along with poverty? What Drake believes is that science is salvific, and extraterrestrial science would be even more salvific than earth’s science.

What we are here calling the ETI myth once sparked the derision of Fred Hoyle over “the expectation that we are going to be saved from ourselves by some miraculous interstellar intervention.”[26] Lewis White Beck exclaims, “exobiology recapitulates eschatology.”[27]

One need not like Hoyle and Beck excoriate astrobiologists or other space researchers for allowing this particular myth to creep through their research door and color the images seen on their telescopes. If anything, the ETI myth is inspiring. It engenders hope. And, of course, we have very little evidence to disconfirm it completely. Believers in the ETI myth may end up with the last laugh after all.

Nevertheless, we need to be cautious in the present. The astrotheologian and other critics should be responsible for distinguishing between fanciful myth and genuine science. In this case, the astrobiologist seems to be practicing theology without a license.

4. Will ETI Cause the Demise of Religion?

The gospel message of the ETI myth is that it is science, not religion, which saves the human race. Further, extraterrestrial science has even more saving power than terrestrial science. This not so hidden antipathy toward traditional religion--traditional religion is allegedly something intelligent beings evolve beyond when they graduate to science--comes to the fore in a secular prophesy: when contact with a more intelligent extraterrestrial civilization is confirmed, then traditional religions will face a crisis of belief, collapse, and die. [28] We might designate this the demise-of-religion-prophecy. Perhaps this prediction deserves a close examination.

Here is an example of the demise-of-religion-prophecy within astrobiology. Jill Tarter, former director of the Center for SETI Research in Mountain View, California, prophesies the coming demise-of-religion. The god of terrestrial religion is our own invention, Tarter contends. It is possible to evolve and grow and get beyond our inherited belief in God. When projecting scenarios onto the history of exoplanets, she constructs an entire scenario based upon the Drake equation. Although to date no contact of any sort with extraterrestrial intelligent life has occurred, Tarter imagines myriads of planets teeming with living beings. All will have evolved. And, if some got a start earlier than us on earth, they will have evolved further. Their technology will have progressed; and they may even have a technology sufficiently advanced to communicate with us. Further, she imagines, these extraterrestrial societies will have achieved a high degree of social harmony and peace so as to support this advanced technology. And, still further, if they have developed their own religion, it too will be more advanced than the religions we have on earth. Or, more likely, the “long-lived extraterrestrials either never had, or have outgrown, organized religion.”[29] We can forecast, then, that contact between earth and ETI will necessitate either the end of our inherited religious traditions or an incorporation of a more universal worldview. In short, Tarter prophesies that this leap forward in terrestrial evolution will leave traditional religion behind while we embrace a more advanced science.

Tarter is a scientist. It is convenient to tell a myth that implies how the myth-teller, in this case the scientist, is already the most highly evolved creature on earth. The only creature superior to a terrestrial scientist would be an extraterrestrial scientist. Myths have the uncanny ability to crown the myth-teller as king or queen.

The forecast of religion’s demise within the ETI myth is articulated also by Davies. “It might be the case that aliens had discarded theology and religious practice long ago as primitive superstition and would rapidly convince us to do the same. Alternatively, if they retained a spiritual aspect to their existence, we would have to concede that it was likely to have developed to a degree far ahead of our own. If they practiced anything remotely like a religion, we should surely soon wish to abandon our own and be converted to theirs. [30] Even with the possibility of extraterrestrial decimation of terrestrial religion, Davies also recognizes the possibility that creative theology on earth might be able to adapt. “The discovery of extraterrestrial life would not have to be theologically devastating.”[31] Theologians may still have a chance, though a slim one, to earn an honest living within the coming scientific millenium.

The assumption at work in the demise-of-religion-prophecy—more forcefully in Tarter than Davies--is that scientists are smart and more highly evolved while religious people are stupid and less evolved. So, a more advanced ETI will be too smart to believe what earthlings believe about God. If ETI connect with us, their superior supra-religious beliefs will, like stepping on an insect, squash our more primitive traditional beliefs.

The very smart scientists on earth already believe what they believe ETI believe; so this makes today’s earthbound scientist a prolepsis of tomorrow’s extraterrestrial genius we have yet to meet. Myths have a curious way of making us emulate the myth-teller.

4.1 Survey Evidence Contradicts the ETI Myth

Might there exist any empirical evidence to substantiate the demise-of-religion-prophecy? Very little if any evidence at all exists to support what ETI myth believers believe about the demise of religion. In fact, evidence to the contrary does exist. Victoria Alexander conducted a survey of U.S. clergy regarding their religious responses to the prospect of extraterrestrial life. She provided clergy from Protestant, Catholic, and Jewish congregations with a set of questions such as: would you agree that “official confirmation of the discovery of an advanced, technologically superior extraterrestrial civilization would have severe negative effects on the country’s moral, social, and religious foundations”? She tabulated her data and concluded: “In sharp contrast to the ‘conventional wisdom’ that religion would collapse, ministers surveyed do not feel their faith and the faith of their congregation would be threatened.”[32] This evidence suggests that the prophesies by astrobiologists regarding the demise of terrestrial religion are a product of their myth, not their science.

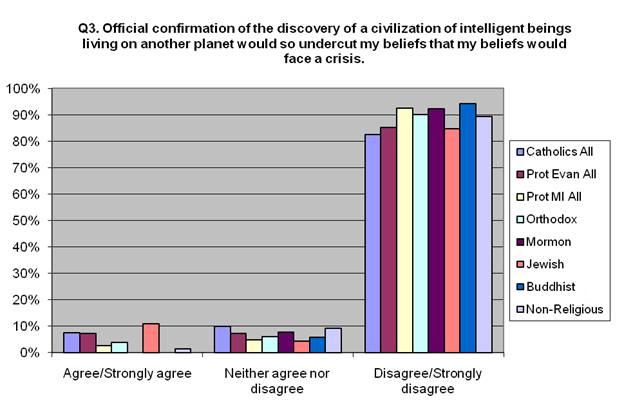

The Peters ETI Religious Crisis Survey[33] confirms and extends the work of Alexander. 1325 respondents--clergy, lay, and religious monks and nuns—were asked: in the event of confirmation of ETI, would a religious crisis result? No evidence of a widespread sense of threat to religion appeared. To the contrary, confidence that the new knowledge of ETI would be incorporated into systems of religious belief was predominant.

Take question 3, for example. Among Roman Catholics, Mainline Protestants, Evangelical Protestants, Orthodox Christians, Mormons, Jews, and Buddhists, the vast majority expect no crisis to develop when learning of ETI. Note further that this refers to their own personal religious belief, which may be distinguishable from the beliefs of the religious tradition with which they self-identify. What is significant is this: if adherents to the world’s religious traditions foresee no threat to their personal beliefs, then the burden of proof that such a threat exists lies on the shoulders of the proponents of the ETI myth-tellers.

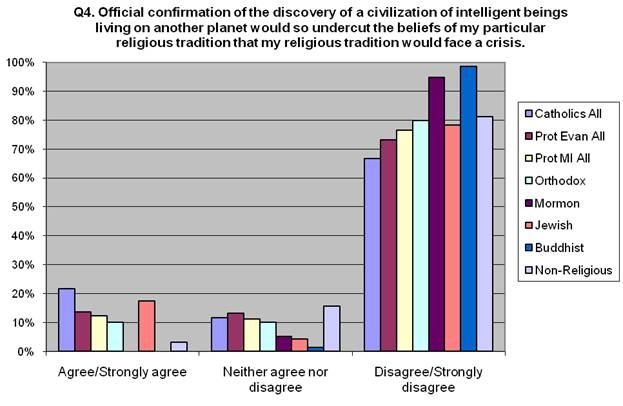

Question 4 requests each individual believer to speak on behalf of his or her religious tradition. This item reveals two things. First, again, the vast majority of adherents to seven tested religious traditions (plus non-religious) perceive no threat of crisis when engaging ETI. Second, the numbers differ slightly from Question 3 reviewed above. Might this mean that one’s religious tradition is more vulnerable to a crisis than one’s own personal belief?

Some light might be shed if we borrow data from another survey. A 2007 survey of more than 35,000 Americans conducted by the Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life uncovered a trend that may be indirectly relevant. Whereas conventional wisdom might suggest that the more religiously zealous a person is the more intolerant he or she would be, the Pew survey indicates that the opposite is true. Zealous Americans are tolerant, even welcoming religious perspectives that differ from their own. To the statement, “many religions can lead to eternal life,” 57 percent of Evangelical Protestants agreed as did 79 percent of Roman Catholics. So did the majority of Jews, Hindus, and Buddhists. What this suggests is “a broad trend toward tolerance and an ability among many Americans to hold beliefs that might contradict the doctrines of their professed faiths.”[34]

Now, the Pew survey is limited to Americans and it does not test directly for openness toward ETI. Nevertheless, if it is in fact the case that many religious people are capable of holding “beliefs that might contradict the doctrines of their professed faiths,” then it might follow that those who welcome ETI into their worldview could do so even if they worry slightly about doctrinal fragility in their own respective religious tradition.

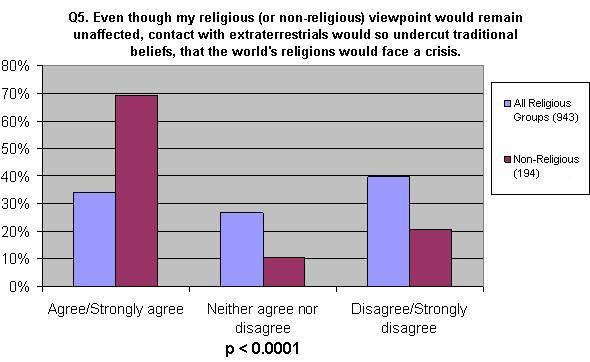

With this as background, note what Question 5 uncovers. Those who identify with a major religious tradition give a modest degree of credence to the forecast that the world’s religions—religions other than their own—might confront a crisis. Some degree of credence, only; yet, still worth noting. Could it be the case that an individual religious believer is slightly more worried about someone else’s beliefs than his or her own?

It is worth giving particular attention to the 205 non-religious persons who responded to the Peters ETI Religious Crisis Survey. A significant majority of those who identify as non-religious tout the demise-of-religion-prophecy. This is twice the average of those who are affiliated with a religious group. Here is the point: the non-religious have a much more negative forecast for religion than do adherents to religion.

What might this demonstrate? Could it demonstrate that many among the non-religious are working with a version of the ETI myth, at least the demise-of-religion-prophecy? Because the Peters ETI Religious Crisis Survey did not test for the ETI myth directly, what we find here is at most suggestive, not conclusive.

Here is a valuable take away conclusion. People who embrace a given religious belief do not fear for their own personal belief; nor are they particularly worried about their own respective religious tradition. A shred of evidence suggests that believers in one religious tradition might be more inclined to impute fragility to other religions to which they do not subscribe or about which they know little. The central finding is this: the hypothesis that the major religious traditions of our world will confront a crisis let alone a collapse is not confirmed by the Peters ETI Religious Crisis Survey. Furthermore, it appears that non-religious persons are much more likely to deem religion fragile and crisis prone than those who hold religious beliefs.

The demise-of-religion-prophecy within the ETI myth finds no empirical support in the Peters ETI Religious Crisis Survey. If anything, the demise-of-religion-prophecy is disconfirmed by the evidence.

5. The ETI Myth Demythologized

The surveys cited above deal with multiple religious traditions in multiple cultures. When we turn specifically to the Christian religion and its theologians, one must ask the question: does myth count in theology? No. Most theologians are willing to interpret myths, but certainly not willing to believe them in their literal form.[35] Myths tell us about human anxieties and propensities, to be sure; but they do not tell us about the reality of God, literally that is. It has long been the task of the theologian to say: don’t believe a myth, literally that is. This would include: avoid believing the ETI as literally true! Science has not demonstrated that it can save us from self-destruction, whether by terrestrial or extraterrestrial science.

The ETI myth is not the exclusive possession of astrobiologists. One can also find the ETI myth at home within theology. Take astrotheologian John Hart, for example. "In the vastness of space and over its eons of time, life on other worlds, too, might have evolved to be intelligent life. Extraterrestrial intelligent life (ETI) might be billions of years older than terrestrial intelligent life (TI)--and considerably more advanced biologically, intellectually, socially, and spiritually."[36] Yes, this is the ETI myth in full blossom in the theologian’s garden. Yet, at the same time, scholars look to such an astrotheologian for a critical pruning of the ETI myth.

The critical astrotheologian can critically illuminate this matter by pointing out two things: first, myth exists in the heart of science and, second, science like everything else human is ambiguous.

5.1 Myth in Religion and Science

First, myth. Modern scientized myths differ in part from ancient religious myths. The latter came in the form of stories, usually stories of creation. Stories of creation taking place in the beginning, in illo tempore, explained why things are the way they are today. "A myth is an intracosmic story that explains why things are as they are," observes philosopher of history, Eric Voegelin.[37]

Today’s scientized myth, in contrast, is not a story about the beginning. Rather, the myth is made up of a set of presuppositions about intracosmic principles that give meaning to the worldview of the myth-teller. These mythical principles are not the conclusions of empirical research. Rather, they are assumptions that place the myth-teller in a position of authority or power. In the instance of the ETI myth, the conceptual set verifies that the scientist can rightfully claim to be the most advanced and trusted source of truth in our society. If science is salvific, then the scientist next door is a candidate for the office of messiah.

5.2 Science as Morally Ambiguous

Second, science, just like all other human enterprises, is fallen. It is ambiguous. It is subject to both evil and good purposes.

Despite the marvels of the new knowledge gained and new technology produced, today’s big science has become subject to the funding of jingoists and the ambitions of militarists. Advances in scientific knowledge lead frequently to equal advances in the breadth and efficiency of murder, mayhem, and mass destruction. Each decade marks a new level of global terror due to advances in nuclear and biochemical weaponry. This spiral is beyond political control, religious control, moral control, and beyond self-control. If the ETI myth suggests that augmenting terrestrial science with extraterrestrial science will provide moral control, the theologian must simply shrug and say: where is the evidence for such a belief?

The blind alley into which the myth leads us—especially the belief in progress—can be called the ‘eschatological problem’.[38] The myth presupposes that if we in our generation simply make the right choice that, with the advance of science, we in the human race can advance from warring destruction to a state of world peace. Yet, the theologian should ask: how do we get from here to there? Can a leopard change its spots so easily? If science got us into a present mess such as the threat of nuclear war or climate change, how can we expect science to liberate us from this mess? If we have evolved to this point, why should we think that more evolving will save us?

Salvific healing, according to the biblical theologian, comes from divine grace granted us within the setting of our fallen life on earth. The cross and resurrection of Jesus Christ symbolize the presence of this saving grace. In the cross we see God’s identification with the victims of human violence. In the resurrection we see God’s promise that we will not forever be locked into the spiral of violence. Unambiguous healing—even world peace—will come to us only as an eschatological transformation, as an act of God. More science will not save us. It is a delusion to think that it will. The theologian, like the rest of us, should welcome and even celebrate the triumphs of science; but these triumphs should not delude us into thinking that science will save us from our human propensity for self-destruction.

Most knowledgeable proponents of the Christian faith in our own time unambiguously embrace the potential presence of ETI as a part of God’s creation. Astronomer-theologian David Wilkinson, for example, holds that “at present there is no strong evidence for extraterrestrial intelligence.[Yet,] as a scientist and a Christian I want to encourage the search for extraterrestrial life and intelligence.”[39]He registers a level of enthusiasm about the speculative prospect of ETI. ”I believe that the discovery of extraterrestrial intelligence would be exciting for the Christian, for it would open up even more of the glory and stunning creativity of the God revealed to us in Jesus.”[40]

6. Conclusion

The ETI myth is a set of presuppositional beliefs widely found among the world’s space scientists, especially those in search of extraterrestrial intelligence. The myth is a supplement for genuine science, not a substitute. It orients and inspires research. But, as myth, it should not in itself be literally interpreted as true.

Again, the ETI myth supplements--it does not replace--authentic science. In this encyclopedia entry we have traced the steps from what is already known scientifically to the conceptual framework that takes on mythical meaning. Here are the steps from sober science to inebriating myth. Step one: insert progress into evolution, even though most evolutionary biologists eschew the doctrine of progress. Step two: assume that civilizations with a longer time for evolution have advanced in intelligence, science, and technology. Step three: assume that advances in science and technology lead to advances in morality that put an end to war. Step four: prophesy that when scientifically and morally more advanced ETI contact us on earth that earth’s many religions will face a crisis of belief and collapse. Step five: prophesy that science alone will thereafter reign on a peaceful planet rarth. In short, the ETI myth asks extraterrestrial science to play the role of messiah, to deliver terrestrial salvation.

This entry has reported that many evolutionary biologists have joined the club of unique earthers, because they repudiate teleology. They repudiate the notion that evolution, once it gets going, is self-directed toward complexity, intelligence, science, and technology. This means that astrobiologists cannot rely on evolutionary biologists to support the ETI myth.

This entry also reported on the Peters ETI Religious Crisis Survey, which falsifies the demise-of-religion-prophecy. This survey, along with some others, demonstrates that self-identified believers in multiple religious traditions deny their beliefs are fragile. Some even would welcome ETI to join them in the pew.

This entry also reported that theologians, specifically Christian astrotheologians, are critical of the place such myth occupies within the heart of science. Astrotheologians should recommend demythologizing, if not complete demythicizing. Neither the ETI myth nor traditional religious myths should be interpreted literally. Myths never have been literal cosmologies, but rather poetic stories which describe our existential place within the observable world in light of that which transcends this world. In sum, the public needs to be warned to listen critically when astrobiologists speak, to separate the science from the myth.

References

- [1] Davies, Paul, “E.T. and God,” The Atlantic Monthly (September 2003) 114-115; http://www.theatlantic.com/issues/2003/davies.htm .

- [2] To demythologize is to interpret a myth, whereas to demythicize is to expunge the myth.

- [3] Kurtz, Paul, The Turbulent Universe. Buffalo NY: Prometheus, 2013; 105, Kurtz's italics.

- [4] This encyclopedia entry updates Peters, Ted, "Astrotheology and the ETI Myth,” Theology and Science, 7:1 (February 2009) 3-30, as well as Astrotheology: Science and Theology Meet Extraterrestrial Life, eds., Ted Peters, Martinez Hewlett, Joshua Moritz, and Robert John Russell. Eugene OR: Cascade Books, 2018; chapter 20.

- [5] The term astrobiology comes from the Greek: αστρο, astro, "constellation"; βίος, bios, "life"; and λόγος, logos, "knowledge." It is the interdisciplinary study of life in the universe, combining aspects of astronomy, biology and geology. It is focused primarily on the study of the origin, distribution and evolution of life. Given the influx of new information about planetary systems around other stars, its mandate has expanded beyond the study of exobiology, from the Greek: έξω, exo, "outside." See the University of Arizona project, “Astrobiology and the Sacred: Implications of Life Beyond Earth,” http://scienceandreligion.arizona.edu/project.html .

- [6] Part of the problem is that progress itself is a myth, so smuggling progress into the ETI myth yields one myth building on another. "Myth of human progress.an overarching story in which human history is pictured as a march towards Utopia, a state of moral perfection both for the society and individual." Wilkinson, David, Science, Religion, and the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence . Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013;126.

- [7] de Duve, Christian, Vital Dust: The Origin and Evolution of Life on Earth. (New York: Basic Books, 1995; 121.

- [8] Brin, Glen David, “The Great Silence: the Controversy Concerning Extraterrestrial Intelligent Life,” Quarterly Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society 24 (1983) 283-309.

- [9] Mayr, Ernst, “The Probability of Extraterrestrial Intelligent Life,” in Extraterrestrials: Science and Alien Intelligence, ed., Edward Regis, Jr. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985; 27.

- [10] Ibid., 25.

- [11] Ruse, Michael, “Is Rape Wrong on Andromeda? An Introduction to Extraterrestrial Evolution, Science, and Morality,” in Extraterrestrials, 50. The ETI myth can be found among some evolutionary theorists, although sociobiologists rather than evolutionary biologists. "Perhaps the extraterrestrials just grew up. Perhaps they found out that the immense problems of their evolving civilizations could not be solved by competition among religious faiths, or ideologies, or warrior nations. They discovered that great problems demand great solutions, rationally achieved by cooperation among whatever factions divided them.there was no need to colonize other star systems. It would be enough to settle down and explore the limitless possibilities for fulfillment on the home planet." Wilson, Edward O., The Social Conquest of Earth. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2012; 296-297.

- [12] Sagan, Carl, and Frank Drake, “The Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence,” Scientific American (January 6, 1997) http://www.sciam.com/article.cfm?id=000B35F3-A4B2-1C59-B882809EC588ED9F&print=true .

- [13] Gould, Stephen Jay, Wonderful Life: The Burgess Shale and the Nature of History. New York: W.W. Norton, 1989; Ayala, Francisco J., "The Evolution of Life on Earth and the Uniqueness of Humankind." in: S. Moriggi and E. Sindoni, eds., Perché esiste qualcosa invece di nulla? (Why There Is Something rather than Nothing?); ITACAlibri: Castel Bolognese, Italy, 2004; 57-77.

- [14] Darling, David, Life Everywhere: The Marverick Science of Astrobiology New York: Basic Books, 2001; 121.

- [15] Ibid.

- [16] Ibid., xi.

- [17] https://www.seti.org/drake-equation-index and https://exoplanets.nasa.gov/news/1350/are-we-alone-in-the-universe-revisiting-the-drake-equation/ .

- [18] Tyson, Neil deGrasse, Michael A. Strauss, and J. Richard Gott, "The Search for Life in the Galaxy," Welcome to the Universe. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press, 2016; 146-169, at 167-168.

- [19] NASA, Astrobiology Roadmap, 18.

- [20] Coyne, George V., S.J., “The Evolution of Intelligent Life on Earth and Possibly Elsewhere: Reflections from a Religious Tradition,” in Many Worlds, 180.

- [21] de Duve, 121.

- [22] Bennett, Jeffrey, Beyond UFOs: The Search for Extraterrestrial Life and Its Astonishing Implications for Our Future. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008; 181, Bennett's italics.

- [23] https://www.westarinstitute.org/blog/what-is-the-gnostic-redeemer-myth/

- [24] Sagan and Drake, “The Search,.”

- [25] Cited by Diane Richards, “Interview with Dr. Frank Drake,” SETI Institute news, 12:1 (First Quarter 2003) 5.

- [26] Hoyle, Fred, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 109: 365 (1949), cited by Wilkinson, David, Alone in the Universe? Crowborough UK: Monarch, 1997;

- [27] Beck, Lewis White, “Extraterrestrial Intelligent Life,” in Extraterrestrials, 13.

- [28] What is the relationship between science and religion? Despite proclamations from prestigious organizations such as the National Academy of Sciences-- “Attempts to pit science and religion against each other create controversy where none needs to exist,” the internet fills the smart phones of twenty-somethings—and thus their assessments—that the world, defined as it is by science and technology, oozes antagonism toward religion. Alvin Plantiga, "Science and Religion: Where the Conflict Really Lies," Science and Religion: Are They Compatible, Daniel C. Dennett and Alvin Plantiga. Oxford UK: Oxford University Press, 2011; 1-24, at 16.

- [29] Jill Cornell Tarter, “SETI and the Religions of the Universe,” in Many Worlds, 146. Davies says, “Tarter’s dismissal is rather naïve…Though many religious movements have come and gone throughout history, some sort of spirituality seems to be part of human nature.” “E.T. and God,” 118.

- [30] Davies, Paul, Are We Alone? London: Penguin, 1995; 37.

- [31] Davies, “E.T. and God,” 118.

- [32] Alexander, Victoria, “Extraterrestrial Life and Religion,” in UFO Religions, ed., James R. Lewis. Amherst NY: Prometheus Books, 2003; 360. The survey conducted by D.A. Vakoch and Y.S. Lee, “Reactions to Receipt of a Message from Extraterrestrial Intelligence: A Cross-Cultural Empirical Study,” Acta Astronomica 46:10-12 (2000) 737-744, is partially relevant, because it suggests that Fundamentalist Christians might confront at crisis at confirmation of ETI.

- [33] This material taken from Peters, Ted, “The implications of the discovery of extra-terrestrial life for religion.” The Royal Society, Philosophical Transactions A, 369 (1936) February 13, 2011; 644-655. http://rsta.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/369/1936.toc . Raw data for the Peters ETI Religious Crisis Survey by Ted Peters and Julie Froehlig can be obtained at http://www.counterbalance.org/etsurv/index-frame.html .

- [34] Neela Banerjee, “Survey Shows U.S. Religious Tolerance,” The New York Times (June 24, 2008) http://www.nytimes.com/2008/06/24us/24religion.html?ex=1214971200&en=fa48d8d17f .

- [35] Rudolph Bultmann gave us the term de-mythologizing. “Its aim is not to eliminate the mythological statements but to interpret them.” Whether the myth is ancient or modern, the theologian does not accept a myth literally. A myth must be interpreted in light of what God reveals regarding divine grace and salvation. Jesus Christ and Mythology New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1958; 18.

- [36] Hart, John, Encountering ETI: Aliens in Avatar and the Americas. Eugene OR: Cascade Books, 2014; 20.

- [37] Voegelin, Eric, Order and History. 5 Volumes: Baton Rouge LA: Louisiana State University Press, 1956-1987; 4:224. "Modern societies, scientific and secular, liberal or communistic, in comprehending and dealing with their historical existence depend as much as did traditional religious societies upon a fundamental mythical structure symbolically expressing.ultimacy and the sacred.myth represents the symbols through which the religious substance of a culture or a community's life in historical passage expresses itself." Gilkey, Langdon, Reaping the Whirlwind: A Christian Interpretation of History. New York: Seabury Crossroad, 1976; 151.

- [38] See: Peters, Ted, Futures—Human and Divine. Louisville KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 1977.

- [39] Wilkinson, Alone in the Universe? 138.

- [40] Ibid., 136.