The Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) genome editing system has been the focus of intense research in the last decade due to its superior ability to desirably target and edit DNA sequences. The applicability of the CRISPR-Cas system to in vivo genome editing has acquired substantial credit for a future in vivo gene-based therapeutic. Challenges such as targeting the wrong tissue, undesirable genetic mutations, or immunogenic responses, need to be tackled before CRISPR-Cas systems can be translated for clinical use. Hence, there is an evident gap in the field for a strategy to enhance the specificity of delivery of CRISPR-Cas gene editing systems for in vivo applications. Current approaches using viral vectors do not address these main challenges and, therefore, strategies to develop non-viral delivery systems are being explored. Peptide-based systems represent an attractive approach to developing gene-based therapeutics due to their specificity of targeting, scale-up potential, lack of an immunogenic response and resistance to proteolysis. In this review, we discuss the most recent efforts towards novel non-viral delivery systems, focusing on strategies and mechanisms of peptide-based delivery systems, that can specifically deliver CRISPR components to different cell types for therapeutic and research purposes.

- CRISPR-Cas

- gene editing

- gene therapy

- non-viral vectors

- cell-penetrating peptides

1. Introduction

The CRISPR genome editing system was first identified as short repeats of DNA downstream of the iap gene of Escherichia coli [1]. In 2002, it was referred to as “CRISPR”, and the CRISPR-associated genes were discovered as highly conserved gene clusters located adjacent to the repeats [2]. A series of studies later revealed that CRISPR is a bacterial immune system that dismantles invading viral genetic material and integrates short segments of it within the array of repeated elements [3][4][3,4]. This array is transcribed and the transcript is cut into short CRISPR RNAs (crRNAs) each carrying a repeated element together with a spacer consisting of the viral DNA segment [5]. This crRNA guides a CRISPR-associated (Cas) nuclease towards invading viral DNA to cleave it and inactivate viral infection at the next occurrence [5]. Starting 2013, the fusion of a crRNA containing a guiding sequence with a trans-activating RNA (tracrRNA) bearing the repeat, into a single-guide RNA (sgRNA) has opened the doors for gene editing in mammalian cell lines and many other species [6][7][8][9][10][6–10].

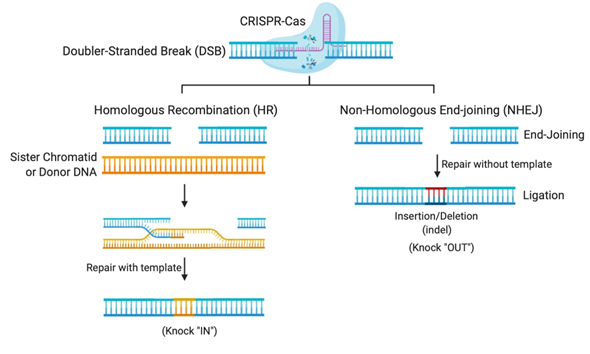

The flexibility of the CRISPR system lies in its programmable Cas nuclease, which utilizes a guide RNA (gRNA) sequence to reach the desired complementary genomic sequence [11]. CRISPR-Cas systems open venues for applications in genetic functional screening, disease modeling, and gene modification [12]. The double-stranded breaks (DSBs) created by the Cas nuclease makes deletions or insertions at precise genomic loci possible [12]. In nature, DSBs can occur randomly during replication or due to environmental factors and are repaired in our cells using the homologous DNA copy as a template in a natural DSB DNA repair process called homology-directed repair (HDR) [13]. This cellular DNA repair pathway can thus be employed to copy a co-introduced artificial DNA template (donor) carrying a desired sequence into the target cleavage site (Figure 1). However, HDR is only activated when the homologous sister chromatid is available, usually in S and G2 phases, during the cell cycle [13]. Otherwise, HDR is suppressed and DSB repair is maintained through a distinct repair pathway called non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ) [13]. In non-dividing cells, such as neurons, gene editing is mostly carried out using NHEJ, where broken DNA ends are directly ligated without any requirement of sequence homology [13]. NHEJ mediated repair, however, is error-prone and tends to produce arbitrary mutations at the site of ligation of DSBs. Often, these mutations create premature stop codons or frame-shifts that are capable of knocking-out the gene of interest, thus providing means to investigate gene function, develop a disease model, or to cease the expression of a harmful mutant protein for therapy [12].

Figure 1. Gene editing by Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR)-Cas systems relies on DNA repair pathways. DNA double-stranded breaks (DSBs) are repaired in cells via the error-prone non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ), or the error-free homologous recombination (HR), the most common form of homology-directed repair (HDR). The DSB repair through NHEJ creates small insertions or deletions (indels), while HDR requires a repair template, which could be a sister chromatid, another homologous region, or an exogenous repair donor.

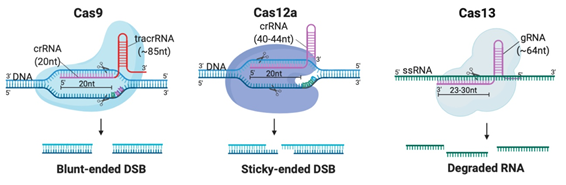

Although CRISPR is not the first site-specific nuclease used in gene-editing, it is the simplest, most rapid, and cheapest of the designer nucleases. CRISPR-Cas systems are classified into 2 classes, 6 types and 33 subtypes, differing in their genes, protein sub-units and the structure of their gRNAs [14]. Class 2 systems have been the most preferred for genetic manipulation, due to their simple design solely involving a sequence-specific monomeric Cas nuclease guided by a variable gRNA molecule [15]. DSBs are created by the Cas nuclease after gRNA aligns with the target DNA sequence via base pair (bp) matching [16]. Thus, only simple modification of the gRNA sequence is enough to target different locations in the genome [12]. The availability of target sites is limited due to the requirement of a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sequence adjacent to the target sequence [16]. But PAMs are highly common and virtually any site in the genome can be targeted [17]. Class 2 CRISPR systems which have been commonly employed for genome editing in mammalian cells with reportedly high efficiency and specificity are summarized in Table 1 and illustrated in Figure 2A [6][15][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29][6,15,17–29].

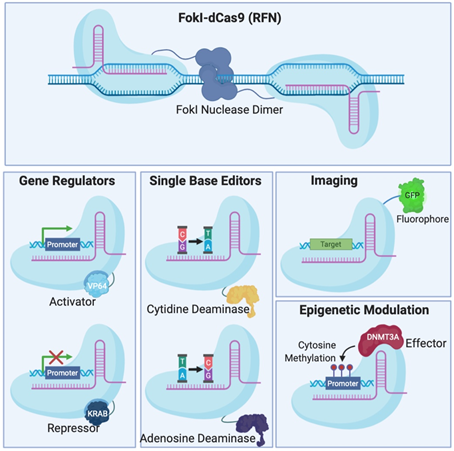

Figure 2. Different Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Pallindromic Repeats (CRISPR)-Cas systems and deficient CRISPR-associated (dCas) platforms used in gene editing and other types of applications. (a) CRISPR-Cas9, 12a and 13 are used mainly in gene editing to target DNA and RNA, respectively. Each platform is composed of two components: the endonuclease sub-unit and single guide RNA (sgRNA). (b) Various CRISPR–dCas-fused platforms used in gene editing such as RNA-guided Flavobacterium okeanokoites (FokI) nuclease (RFN), Base editing (cytidine deaminases and adenosine deaminases), Gene regulators (transcriptional activators such as VP46, transcriptional repressors such as KRAB), imaging (fluorescent protein tags such as GFP) and epigenetic modulation (transcriptional modulators such as DNMT3A for cytosine methylation).

Table 1.

Class 2 CRISPR systems which employed for therapeutic genome editing.

|

Class |

Type |

Nuclease |

gRNA Structure |

Target |

Cleavage |

||||

|

crRNA |

tracrRNA |

gRNA Length |

Molecule |

PAM |

Availability in Human Genome |

||||

|

2 |

2 |

Cas9 |

20nt (complementary to target) |

85nt |

105nt |

dsDNA |

5′-NGG (SpCas9) |

Every ~8 bp |

Blunt-ended DSB |

|

5 |

Cas12 |

40nt (20-24nt complementary to target) |

None |

40nt |

dsDNA |

5′-TTTN |

Every ~23 bp |

Sticky-ended DSB |

|

|

6 |

Cas13 |

64nt (23-30nt complementary to target) |

None |

64nt |

ssRNA |

None |

Any location |

Arbitrary cleavage around target site |

|

Abbreviations: gRNA (guide-RNA), crRNA (CRISPR RNA), tracrRNA (trans-activating RNA), PAM (protospacer adjacent motif), Cas9 (CRISPR-associated protein 9), nt (nucleotide), bp (base pair), dsDNA (double-stranded DNA), SpCas9 (Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9), DSB (double-stranded break), Cas12 (CRISPR-associated protein 12), Cas13 (CRISPR-associated protein 13), ssRNA (single-stranded RNA).

To avoid inherent problems associated with the formation of DNA DSBs in cells, researchers have fused catalytically deficient Cas9 (dCas9) to single-base editors that can convert single nucleotides without the need to create a DSB which is very attractive for the development of gene therapy [30][31][30,31]. Fusion of dCas9 with other proteins can also serve as regulators of gene expression [32][33][34][35][32–35], epigenetic histone re-modulators [36], or fluorescent reporters for genome labelling [37] (Figure 2B).

2. Potential and Application of CRISPR Therapeutics

CRISPR-Cas systems discussed above have the ability to be used for the development of corrective gene therapeutics for a huge number of genetic mutations contributing to disease [38][39][40][38–40]. In only a few years after its discovery, CRISPR had already transformed the field of biomedical research, with the first Food and Drug Administration-approved ex vivo clinical trial started in 2018 [41] and the first in vivo clinical trial in 2019 [42] along with numerous clinical trials under way as of today. CRISPR therapies being tested in clinical trials launched by Vertex and CRISPR Therapeutics in 2018 (CTX001) [41] and Allife Medical Science and Technology Co., Ltd. in 2019 (HBB HSC-01) [43], aim to treat patients with β-thalassemia and sickle-cell disease by the autologous transfusion of CRISPR/Cas9-edited CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells. Patients receiving CTX001 showed progress after a few months [44], which is indicative of the success of CRISPR application in gene therapy. EDIT-101, is being tested by Allergan and Editas Medicine since 2019 [45], to correct a CEP290 splicing defect in patients of Leber Congenital Amaurosis, after showing significant therapeutic potential in a preclinical study [46]. These particular CRISPR therapies, and similar ones tackling hemoglobinopathies or eye diseases, entertain a key advantage over several others, listed below, which are “stuck” in their preclinical stages. This main advantage is the route of administration employed. Essentially, CTX001 and HBB HSC-01 involve ex vivo genome editing of cells which are transferred back to patients [41][43][41,43]. On the other hand, EDIT-101 is applied to patients intraocularly; a mode of delivery generally used for its local effects [45]. This circumvents the need for establishing a safe and efficient method of delivery that can reach the organ of interest within the human body, a major hurdle facing the translation of most CRISPR therapeutics to the clinic today.

To list a few examples of preclinical advances in CRISPR therapy, multiple groups have been successful in treating hereditary tyrosinemia I, using Cas9, in disease models by correcting disease-causing FAH mutations[47][48] [47,48] or knocking-out HPD [49]. Similarly, researchers applied Cas9 to effectively correct a disease causing mutation in CFTR to treat monogenic cystic fibrosis in patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells [50][51][50,51]. Cas13 was developed as an antiviral to target the genomes of RNA viruses such as Influenza and SARS-CoV-2 in human lung epithelial cells to combat airway diseases [52]. An ambitious approach towards modern airway disease pandemics with no current preventative vaccines or proven treatment, where the authors explain the necessity of finding an effective in vivo delivery method to the lungs [52]. Several promising strategies towards neurodegenerative diseases, currently with no cure, have also been reported. For example, using Cas9 to knock-out the expression of mutant amyloid precursor protein (APP) was demonstrated to have neuroprotective effects in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease [53]. One more notable approach utilizes Cas13 to convert the abundant astrocytes in the brain into dopaminergic neurons that are lost in Parkinson’s Disease in order to restore motor behavior in mice [54]. This latter example highlights the breadth of CRISPR’s therapeutic application especially because it tackles the disease using a cell-conversion strategy rather than editing a disease-causing mutation. Indeed, biomedical research has already developed various strategies for CRISPR therapy that can halt or reverse disease progression. However, the translation of such therapies is contingent upon the development of appropriate modes of delivery.

3. Conclusion

Although the field of CRISPR therapy has flourished during the last decade, there remains a need for developing appropriate targeted delivery systems to advance its use to the clinic. Developing non-viral delivery systems for CRISPR have been a subject of immense research to avoid the safety concerns associated with viral vectors. Thus far, most targeted delivery systems employed for CRISPR-Cas are dependent on ligand-decorated liposomes or nanoparticles, which require complex design or may be toxic to achieve cell-specific receptor recognition. Peptide-based non-viral delivery systems contain properties that offer advantages such as chemical diversity, low toxicity, resistance to proteolysis and ability for specific targeting. The non-covalent complexing of CRISPR-Cas components with peptides through charge–charge interactions represents a one-step, simple, safe, translatable, and customizable method for specific tissue targeting. Targeting CRISPR-Cas systems to the cells of interest carries a great deal of hope for biomedical research and for achieving the safety levels required for clinical translation. More research is needed to test the efficacy of peptide-based systems for the targeted in vivo delivery of CRISPR-Cas to different tissues.