Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Pistachio nuts are a plant-based complete protein providing all nine essential amino acids (EAA) in addition to an array of nutrients and phytochemicals. They have a Protein Digestibility-Corrected Amino Acid Score (PDCAAS) of 73 and 81%, (raw and roasted pistachios, respectively), higher than that of many other tree nuts. From an environmental perspective transitioning towards plant-based diets (including nuts) could have potential to reduce total/green water footprints.

- pistachio

- protein demands

- protein diversity

- protein quality

- health benefits

1. Introduction

Plant-based diets are growing in popularity globally for an array of reasons which includes concerns for human and planetary health [1][2]. Concepts of what constitutes a ‘plant-based’ diet vary considerably, with present definitions ranging from the elimination of all animal products to diets including dairy, fish and meat in variable amounts [3]. There have been concerns, however, that plant-based diets provide lower levels of the nine essential amino acids (EAA), including specific amino acids, such as leucine, sulphur amino acids and lysine [4][5][6][7]. Compared with animal-derived proteins it is further alleged that plant-proteins have less of an anabolic effect, due to their lower digestibility and the amino acids being directed towards oxidation rather than muscle protein synthesis (MPS) [7]. It is well appreciated that within the general population misconceptions exist about what constitutes health eating, even more so with goalposts ever shifting in terms of what defines a healthy diet [8][9]. From a consumer behaviour perspective, enjoyment of meat, unwillingness to make dietary changes and health concerns could act as potential obstacles to the shift towards plant-based diets [10]. From a historical standpoint across pre-agricultural hunter-gatherer societies, meat was regarded as a ‘highly prized food’ and today still has strong associations with masculinity [11].

The EAT-Lancet 2019 Food in the Anthropocene report was revolutionary in that it accentuated the need to review food systems and their dual impacts on health and planetary outcomes and included a modelled healthy reference diet that was predominantly plant-based [12]. The EAT-Lancet healthy reference diet advised that this “largely consists of vegetables, fruits, whole grains, legumes, nuts, and unsaturated oils” and as a key message concluded that the transformation to healthy diets by 2050 will require substantial dietary shifts, including a greater than 100% increase in consumption of foods, such as nuts, fruits, vegetables and legumes [12]. Within this guidance, peanuts were listed as a separate protein food source within the legumes category (with a possible daily intake range of 0–75 g) and tree nuts, which would encompass pistachios, were also listed as a separate category (possible intake of 25 g/day) [12]. The EAT Lancet dietary guidance therefore recognises the role of nuts as a key plant protein source.

2. Protein in Pistachios

The Protein Digestibility-Corrected Amino Acid Score (PDCAAS) of only a few nuts has been evaluated. In 2020 a standardised ileal digestibility study measured both the DIAAS and PDCAAS score of raw and roasted pistachio nuts [13]. Raw and roasted pistachio nuts had a PDCAAS of 73% and 81%, respectively, calculated for children 2–5 years, with the limiting amino acid being threonine in the calculation. The DIAAS was 86 and 83 for raw and roasted pistachio nuts, respectively, calculated for children older than 3 years, adolescents and adults, with the limiting amino acid being lysine [13]. Taken together, these results demonstrated that both raw and roasted pistachio nuts had a DIAAS greater than 75, thus were recognised as being ‘good quality’ protein sources [13].

The PDCAAS of other nuts has also been determined. The protein digestibility of cashew nuts, peanuts and Brazil nuts and their PDCAAS have been calculated to be 90.3%, 69.3% and 63.3%, respectively [14]. For raw almonds, a PDCAAS between 44.3 and 47.8% was equated for children aged 2–5 years [15]. For walnuts, a PDCAAS of 46% has been calculated for children aged 3–10 years [16]. In most of these studies the specified limiting EAA was lysine [13][14][15]. Researchers have recently compiled a database of amino acids in plant-sourced foods [17]. The amino acid found to be present in the greatest concentration for both raw and roasted pistachio nuts has been found to be arginine, with leucine being the second most abundant in concentration [13]. Other research shows that free amino acids represented ≤3.1% of total AAs in pistachio nuts, soybeans, corn grains, white rice and wheat flour and 34.4% and 28.5% in potatoes and sweet potatoes, respectively [17]. Subsequently, as shown in Table 1, a PDCAAS of 73 and 81%, respectively, for raw and roasted pistachios is higher than scores calculated for almonds, Brazil nuts, peanuts, pecans and walnuts. It is also higher than PDCAAS derived for white rice, chickpeas, red kidney beans and certain lentils (whole green, red and yellow split lentils). The PDCAAS of roasted pistachios was only marginally lower than that of chicken, beef and egg powder. This demonstrates that plant-based pistachios are a balanced and good quality protein source.

Table 1. PDCAAS Comparisons of Different Protein Foods.

| Foods | PDCAAS (%) | Age for Standard Amino Acid Requirement | Reference Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Almonds, nuts, raw | 44–48% | 2–5 years | House et al. (2019) [15] |

| Almonds, Baru, roasted | 56.6% | 2–5 years | Freita et al. (2012) [14] |

| White rice, cooked | 56% | Healthy young men | Prolla et al. (2013) [18] |

| Beef, dried beef, ground | 92.4% | 2–5 years | Boye et al. (2012) [19]; Pires et al. (2006) [20] |

| Brazil nuts, dried, raw | 63.3% | 2–5 years | Freitas et al. (2012) [14] |

| Cashew nuts | 90.3% | 2–5 years | Freitas et al. (2012) [14] |

| Chicken, fresh breast meat, dried | 95.2% | NCS | Negrão et al. (2005) [21] |

| Chickpeas, canned, drained solids | 52% | NCS | Nosworthy et al. (2017) [22] |

| Egg, lyophilised powder | 90.1% | 2–5 years | Boye et al. (2012) [19] Pires et al. (2006) [20] |

| Red kidney beans | 55% | -- | Nosworthy et al. (2017) [22] |

| Lentils, whole green | 63% | -- | Nosworthy et al. (2017) [22] |

| Lentils, split red | 54% | -- | Nosworthy et al. (2017) [22] |

| Lentils, split yellow | 64% | -- | Nosworthy et al. (2017) [22] |

| Peanuts, roasted | 69% | 2–5 years | Freitas et al. (2012) [14] |

| Pecans | 59% | -- | Tanwar et al. (2022) [23] Calculated value * |

| Pine nuts | 73% | -- | Calculated value * |

| Pistachio nuts, raw | 73% | 2–5 years | Bailey et al. (2020) [13] |

| Pistachio nuts, roasted | 81% | 2–5 years | Bailey et al. (2020) [13] |

| Walnuts | 39% 46% |

6 months–3 years (Child) 3–10 years (Older child, adolescent, adult) |

Lackey et al. (2021) [16] |

Key: -- Not clearly specified. * Calculated value, from USDA amino acid content (USDA database [24]), using the percentage of the limiting amino acid (lysine) from the amino acid profile requirement for children 3 to 5 years of age (FAO [25][26]) and multiplying by true digestibility ([23]). Pistachio nuts highlighted in grey.

There is increased recognition, however, that we should be focusing on the ‘totality of diets’ rather than whether or not individual foods provide all nine EAA [27]. People ingest mixed diets, thus it is the amino acid composition of the overarching diet that will determine protein adequacy [27]. Thus, the concept of protein diversification, with protein from a range of food sources beyond those that are animal-derived, is gaining interest [28][29].

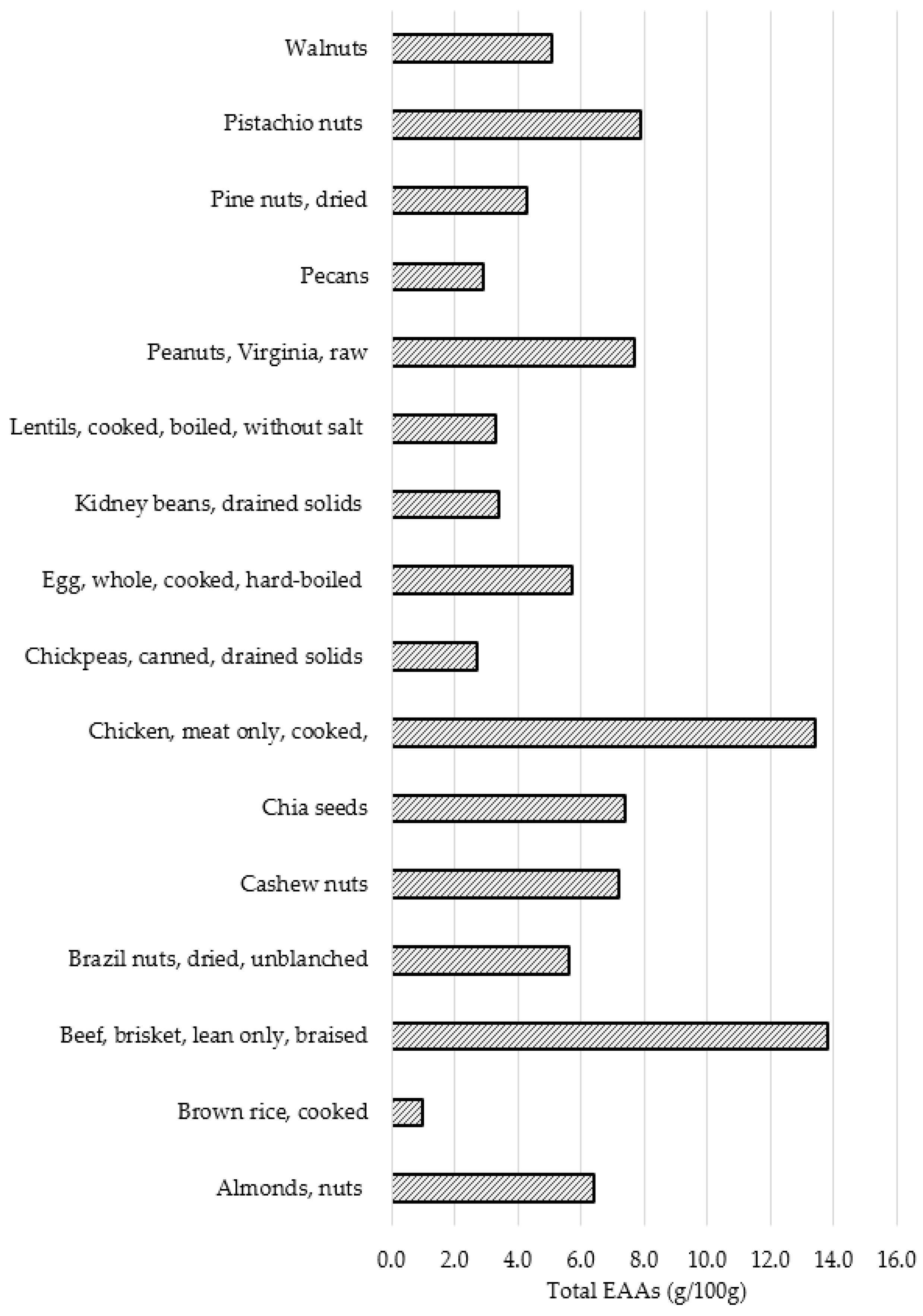

As demonstrated in Table 2 different foods provide an assortment of different amino acids. Pistachio nuts are a complete protein providing all nine EAAs along with 4.3 g glutamic acid per 100 g (comparable with beef brisket) and 2.1 g arginine per 100 g (comparable with chicken). After braised beef brisket and cooked chicken, pistachios provide the next highest levels of total EAAs (7.9 g/100 g). Pistachios also provide a higher level of branched chain amino acids compared with other nuts and foods such as brown rice and lentils. Figure 1 further demonstrates that pistachios are an important provider of EAAs.

Figure 1. Total Essential Amino Acids (g/100 g) of Different Protein Foods.

Table 2. The Amino Acid Profiles of Different Protein Foods.

| Amino Acids | Almonds, Nuts | Brown Rice, Cooked | Beef, Brisket, Lean Only, Braised | Brazil Nuts, Dried, Unblanched | Cashew Nuts | Chicken, Meat Only, Cooked, Grilled | Chickpeas, Canned, Drained Solids | Egg, Whole, Cooked, Hard-Boiled | Kidney Beans, Drained Solids | Lentils, Cooked, Boiled, without Salt | Peanuts, Virginia, Raw | Pecans | Pine Nuts, Dried | Pistachio Nuts | Walnuts |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alanine | 1.0 | 0.2 | 1.8 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 1.8 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 1.0 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 0.7 |

| Arginine | 2.5 | 0.2 | 1.9 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 3.0 | 1.2 | 2.4 | 2.2 | 2.3 |

| Aspartic acid | 2.6 | 0.2 | 2.7 | 1.3 | 1.8 | 2.9 | 0.8 | 1.3 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 3.1 | 0.9 | 1.3 | 2.0 | 1.8 |

| Cystine | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 |

| Glutamic acid | 6.2 | 0.5 | 4.5 | 3.2 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 1.2 | 1.6 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 5.3 | 1.8 | 2.9 | 4.5 | 2.8 |

| Glycine | 1.4 | 0.1 | 1.8 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 1.4 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 1.5 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 1.1 | 0.8 |

| Histidine * | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.9 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 1.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| Isoleucine *,b | 0.8 | 0.1 | 1.4 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 1.5 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 0.6 |

| Leucine *,b | 1.5 | 0.2 | 2.4 | 1.2 | 1.5 | 2.5 | 0.5 | 1.1 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 1.6 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 1.7 | 1.2 |

| Lysine* | 0.6 | 0.1 | 2.5 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 2.9 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 1.2 | 0.4 |

| Methionine * | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.8 | 1.1 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.2 |

| Phenylalanine * | 1.1 | 0.1 | 1.2 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 1.3 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 1.1 | 0.7 |

| Proline | 1.0 | 0.1 | 1.4 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 1.1 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 0.7 |

| Serine | 0.9 | 0.1 | 1.2 | 0.7 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 1.2 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 1.3 | 0.9 |

| Threonine * | 0.6 | 0.1 | 1.2 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 1.4 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.9 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 0.6 |

| Tryptophan * | 0.2 | 0.0 | 2.0 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.2 |

| Tyrosine | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.9 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 1.1 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 1.0 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| Valine *,b | 0.9 | 0.2 | 1.4 | 0.8 | 1.1 | 1.6 | 0.3 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 1.0 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 1.3 | 0.8 |

| BCAAs | 3.2 | 0.5 | 5.2 | 2.5 | 3.4 | 5.6 | 1.1 | 2.6 | 1.6 | 1.5 | 3.5 | 1.3 | 2.2 | 4.0 | 2.6 |

| EAAs | 6.4 | 1.0 | 13.8 | 5.6 | 7.2 | 13.4 | 2.7 | 5.7 | 3.4 | 3.3 | 7.7 | 2.9 | 4.3 | 8.2 | 5.1 |

| NEAAs | 16.3 | 1.5 | 16.6 | 10.0 | 12.9 | 16.3 | 4.3 | 7.0 | 4.7 | 5.0 | 17.5 | 6.1 | 10.3 | 13.8 | 10.6 |

| Data source/NDB Number | 12,061 | 20,037 | 13,368 | 12,078 | 12,087 | 5747 | 16,358 | 1129 | 16,145 | 16,070 | 16,095 | 12,142 | 12,147 | 12,152 | 12,155 |

Key: b, BCAAs branched chain amino acids; * EAAs, essential amino acids; NEAAs, nonessential amino acids (highlighted in grey). Source: USDA Food Data Central (2022) [24].

Mariotti and Gardner (2019) recently explained there have been concerns that amino acid intakes from vegetarian diets are often perceived as being inadequate, but the integration of nuts, seeds, and legumes within diets can be sufficient in terms of achieving full protein adequacy in adults, provided that energy needs are being met and a variety of foods are being consumed [30]. Pistachios are therefore positioned as a useful protein source, delivering good-quality plant-based protein, fibre, a range of healthy fats, including mono- and polyunsaturated fatty acids whilst being low in saturated fatty acids and providing an array of micronutrients and bioactive compounds [31][32][33].

3. Health Benefits of Pistachios

As described, according to European Commission regulations, pistachios are high in’ fibre, monounsaturates, copper, chromium, vitamin B6, thiamine, manganese, phosphorus and potassium and ‘a source’ of protein, vitamin E, K, folic acid, riboflavin, magnesium, iron, zinc and selenium. Pistachios also provide an array of vitamins and minerals alongside anthocyanins, carotenoids, flavonoids and phenolic acids [34][35].

They provide a spectrum of phenolic compounds, with at least 9 lipophilic and 11 hydrophilic bioactive being identified [36]. Most of the phenolics are present in the skin and the lipophilic constituents tend to be present in the nutmeat [36]. Research examining the phytochemical profile of American raw and roasted pistachios found that free-form contributions to the total phenolics were 82% and 84% for raw and roasted pistachios, respectively, and free-form contributions to the total flavonoids were 65% and 70% for raw and roasted pistachios, respectively [32]. For raw and roasted pistachios, gentisic acid and catechin were the predominant phenolics [32].

Polyphenols in pistachios are known to exert antioxidative and anti-inflammatory effects [34][37] and a range of publications have now documented their wider health effects [31][33][34][37][38].

3.1. Body Weight

Several studies have focused on inter-relationships between pistachio ingestion and markers of body weight and composition [39][40][41][42][43][44][45]. A randomised controlled study found that overweight/obese adults who ingested 42 g/day of pistachios alongside a weight-loss intervention had significantly increased intakes of fibre, ingested fewer sweets, and exhibited similar levels of weight loss to the control [39].

An extensive 24-week trial recruiting Asian Indians showed that daily consumption of unsalted pistachios (20% energy) significantly improved waist circumference and markers of metabolic syndrome (total-cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein, free fatty acids and adiponectin levels) [40]. Research with Chinese adults with metabolic syndromes similarly found that ingesting 42 g or 70 g pistachios daily for 12 weeks did not contribute to weight gain nor increased waist-to-hip ratio [41].

Research focusing on snacking, comparing the ingestion of 53 g of salted pistachios to 56 g of salted pretzels over 12 weeks by obese adults found that BMI declined significantly from 30.1 to 28.8 in the pistachio group compared with a 0.6 decline in the pretzel group [42]. Other work has shown that amongst healthy-weight women, 44 g (259 kcal) of pistachios daily can improve nutrient intake and induce satiety without impacting on body weight or composition [43][45]. Research by Bellisle et al. [45] showed that calories provided by pistachio snacks induced satiety and induced energy compensation in healthy women. As an afternoon snack, 56 g of pistachios (versus 56 g energy/protein matched savoury biscuits) did not influence body weight but did improve the micronutrient profile (thiamine, vitamin B6, potassium and copper) of French women, when consumed over four weeks [44].

Taken together, pistachios may help regulate body weight because of their satiety and satiation effects along with their reduced net metabolizable energy content [38]. Their fatty acid profile when consumed in moderation does not appear to impact on body weight and should be viewed as a heart-healthy fatty acid profile rather than one posing risk to gains in body weight.

3.2. Diabetes and Prediabetes

Pistachio constituents possess antioxidant and anti-inflammatory functions which may exert regulatory effects, including glucose- and insulin-lowering effects [34][46][47][48]. Kendall et al. (2011) [49] showed that pistachios (28, 56, and 84 g) added to white bread contributed to a dose-dependent reduction in glycaemic responses. The same team later showed that pistachio ingestion (versus white bread) reduced postprandial glycaemia and increased glucagon-like peptide levels [50]. A publication reanalysing data looking at nuts as a replacement for carbohydrates in diabetes diets further reconfirmed their role in improving glycaemic control in type 2 diabetes [51][52].

The Carlos Gestational Diabetes Mellitus (GDM) prevention study showed that early nutritional intervention with a Mediterranean diet that included pistachios reduced the risk of GDM and improved several maternal and neonatal outcomes, including rates of insulin-treated GDM, prematurity, excess gestational weight gain and rates of small and large-for gestational age infants [53][54][55]. Other research [56] conducted by Feng et al. (2019) investigated the acute effects of two isocaloric test meals—42 g of pistachios and 100 g of whole-wheat bread in Chinese women with GDM or gestational-impaired glucose tolerance. Pistachio intake resulted in significantly lower postprandial glucose, insulin and gastric inhibitory polypeptide and higher glucagon-like peptide-1 levels compared with whole-wheat bread, indicating that these would be a healthy snack choice during pregnancy [56].

Other factors such as telomere erosion have been linked to type 2 diabetes pathogenesis and severity [57]. A randomised crossover clinical trial allocated 49 prediabetic adults to consume a diet providing 57 g of pistachios daily or a calorie-matched control diet over four months with a two-week washout period [57]. The pistachio-supplemented diet significantly reduced DNA oxidative damage and upregulated telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) expression, which was inversely correlated to fasting plasma glucose levels [57]. Other work shows that similar intakes of pistachios (57 g/day) favourably alters microRNA expression linked to insulin sensitivity [58].

3.3. Heart Health

The U.S. FDA authorised the health claims that: “scientific evidence suggests but does not prove that eating 1.5 oz (42.5 g) per day of most nuts, such as pistachios, as part of a diet low in saturated fat and cholesterol may reduce the risk of heart disease” in 2003 [59].

Nuts are well recognised for their role in reinforcing heart health with a recent meta-analysis showing that nut consumption had a beneficial effect on reducing the incidence of (and mortality from) different cardiovascular disease outcomes [60]. A meta-analysis of 11 randomised controlled trials demonstrated that pistachio consumption improved cardiometabolic risk factors, including fasting blood sugar, insulin levels, systolic blood pressure and blood lipid profile [61].

A randomised trial comprised of 30 adults (40 to 74 years) demonstrated that pistachio nut consumption (replacement of low-fat or fat-free carbohydrate snacks with pistachios equivalent to 20% of daily energy (range: 59 to 128 g) depending on calorie assignment) improved certain cardiovascular risk factors, including heart rate variability and systolic blood pressure, with the latter observed most prominently during sleep [62]. Other early work [63] showed that diets providing 15% of calories as pistachio nuts (2–3 ounces; 57–85 g per day) improved certain lipid profiles in individuals with moderate hypercholesterolemia.

Ros et al. (2021) concluded that regular nut consumption is an indispensable component of any healthy, plant-based diet and that a daily dose of at least 30 g/d of a mixture of nuts, is ideal for optimising health [64]. The Global Burden of Disease Study (2017) estimated 21 g per day as the optimal intake of nuts and seeds after evaluating the health ramifications of suboptimal diets [65].

Subsequently, nuts appear to be an important dietary component for reinforcing heart health. Increasingly, plant-based dietary patterns are being viewed as beneficial for dyslipidaemia management, the prevention of cardiovascular disease risk and being environmentally sustainable [66].

3.4. Cancer

Tree nut intake has been shown to be associated with a significantly reduced incidence of colon cancer recurrence and mortality [67][68], pancreatic cancer [69][70] and overall cancer mortality [71][72][73]. Focusing on pistachios, in vitro and in vivo trials suggest that pistachio consumption could have a beneficial impact on cancer development [74]. Yuan et al. (2022) extracted free and bound phytochemical compounds in raw and roasted pistachios, finding that these demonstrated potent antioxidant and antiproliferative activities [32]. The free-form extracts of roasted pistachios exhibited relatively high antiproliferative capacity towards liver HepG2 (a human liver cancer cell line), along with colon Caco-2 and breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cells in a dose-dependent manner [32]. Of the extracts tested, roasted free extracts exhibited higher anticancer activities although free extracts of roasted pistachios had exceptionally high activity against human breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cells [32]. Other research by Glei et al. (2017) demonstrated chemopreventive potential of pistachio nuts using in vitro colon adenoma cells [74]. This effect was mediated by growth inhibition, the induction of apoptosis and anti-genotoxic effects, along with the induction of detoxifying enzymes [74]. Work has further shown that fermented pistachio milk possesses anti-colon cancer properties, which could be attributed to its acetate content [75].

3.5. Other Potential Benefits

Pistachios and pistachio extracts appear to play further roles in cognitive function, inducing neurobehavioral and neurochemical modifications [76][77] and exerting anxiolytic (anti-anxiety) effects [78][79]. Pistachio consumption also been linked to restoration of gut microbiota composition, with improved Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus, Turicibacter and Romboutsia (beneficial bacteria) profiles [80][81]. Interestingly, after four weeks of prediabetic adults ingesting 57 g/day of pistachios, the urine profile of gut-microbiota metabolites altered significantly [82]. Further research has found that the ingestion of mixed tree nuts (1.5 oz over 12 weeks) affects tryptophan and microbial metabolism in overweight and obese subjects [83]. Changes in gut microbiota is an emerging area of research needing more attention.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/nu15092158

References

- Craig, W.J.; Mangels, A.R.; Fresan, U.; Marsh, K.; Miles, F.L.; Saunders, A.V.; Haddad, E.H.; Heskey, C.E.; Johnston, P.; Larson-Meyer, E.; et al. The Safe and Effective Use of Plant-Based Diets with Guidelines for Health Professionals. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4144.

- Aimutis, W.R. Plant-Based Proteins: The Good, Bad, and Ugly. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 13, 1–17.

- Storz, M.A. What makes a plant-based diet? A review of current concepts and proposal for a standardized plant-based dietary intervention checklist. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 76, 789–800.

- Pinckaers, P.J.M.; Trommelen, J.; Snijders, T.; van Loon, L.J.C. The Anabolic Response to Plant-Based Protein Ingestion. Sport. Med. 2021, 51, 59–74.

- Ewy, M.W.; Patel, A.; Abdelmagid, M.G.; Mohamed Elfadil, O.; Bonnes, S.L.; Salonen, B.R.; Hurt, R.T.; Mundi, M.S. Plant-Based Diet: Is It as Good as an Animal-Based Diet When It Comes to Protein? Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2022, 11, 337–346.

- Nichele, S.; Phillips, S.M.; Boaventura, B.C.B. Plant-based food patterns to stimulate muscle protein synthesis and support muscle mass in humans: A narrative review. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2022, 47, 700–710.

- Berrazaga, I.; Micard, V.; Gueugneau, M.; Walrand, S. The Role of the Anabolic Properties of Plant- versus Animal-Based Protein Sources in Supporting Muscle Mass Maintenance: A Critical Review. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1825.

- Dickson-Spillmann, M.; Siegrist, M. Consumers’ knowledge of healthy diets and its correlation with dietary behaviour. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2011, 24, 54–60.

- Cena, H.; Calder, P.C. Defining a Healthy Diet: Evidence for The Role of Contemporary Dietary Patterns in Health and Disease. Nutrients 2020, 12, 334.

- Corrin, T.; Papadopoulos, A. Understanding the attitudes and perceptions of vegetarian and plant-based diets to shape future health promotion programs. Appetite 2017, 109, 40–47.

- Love, H.J.; Sulikowski, D. Of Meat and Men: Sex Differences in Implicit and Explicit Attitudes Toward Meat. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 559.

- Willett, W.; Rockstrom, J.; Loken, B.; Springmann, M.; Lang, T.; Vermeulen, S.; Garnett, T.; Tilman, D.; DeClerck, F.; Wood, A.; et al. Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT-Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet 2019, 393, 447–492.

- Bailey, H.M.; Stein, H.H. Raw and roasted pistachio nuts (Pistacia vera L.) are ‘good’ sources of protein based on their digestible indispensable amino acid score as determined in pigs. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2020, 100, 3878–3885.

- Freitas, J.; Fernandes, D.; Czeder, L.; Lima, J.; Sousa, A.; Bnaves, M. Edible Seeds and Nuts Grown in Brazil as Sources of Protein for Human Nutrition. Food Nutr. Sci. 2012, 3, 20057.

- House, J.; Hill, K.; Neufeld, J.; Franczyk, A.; Nosworthy, M. Determination of the protein quality of almonds (Prunus dulcis L.) as assessed by in vitro and in vivo methodologies. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 7, 2932–2938.

- Lackey, K.A.; Fleming, S.A. Brief Research Report: Estimation of the Protein Digestibility-Corrected Amino Acid Score of Defatted Walnuts. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 702857.

- Hou, Y.; He, W.; Hu, S.; Wu, G. Composition of polyamines and amino acids in plant-source foods for human consumption. Amino Acids 2019, 51, 1153–1165.

- Prolla, I.R.; Rafii, M.; Courtney-Martin, G.; Elango, R.; da Silva, L.P.; Ball, R.O.; Pencharz, P.B. Lysine from cooked white rice consumed by healthy young men is highly metabolically available when assessed using the indicator amino acid oxidation technique. J. Nutr. 2013, 143, 302–306.

- Boye, J.; Wijesinha-Bettoni, R.; Burlingame, B. Protein quality evaluation twenty years after the introduction of the protein digestibility corrected amino acid score method. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 108 (Suppl. 2), S183–S211.

- Pires, C.V.; Almeida Oliveira, M.G.D.; Cesar Rosa, J. Nutritional quality and chemical score of amino acids from different protein sources. Cienc. Tecnol. Aliment. 2006, 26, 179–187.

- Negrão, C.C.; Mizubuti, I.Y.; Morita, M.C.; Colli, C.; Ida, E.I.; Shimokomaki, M. Biological evaluation of mechanically deboned chicken meat protein quality. Food Chem. 2005, 90, 579–583.

- Nosworthy, M.G.; Neufeld, J.; Frohlich, P.; Young, G.; Malcolmson, L.; House, J.D. Determination of the protein quality of cooked Canadian pulses. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 5, 896–903.

- Tanwar, B.; Modgil, R.; Goyal, A. Protein Quality Assessment of Pecan and Pine (Pinus gerardiana wall.) Nuts for Dietary Supplementation. Nutr. Food Sci. 2022, 52, 641–656.

- U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). Agricultural Research Service. FoodData Central. Available online: https://fdc.nal.usda.gov/ (accessed on 16 January 2023).

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations). FAO Expert Working Group: Research Approaches and Methods for Evaluating Protein Quality of Human; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2014.

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations). Dietary Protein Quality Evaluation in Human Nutrition: Paper 92; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2013.

- Katz, D.L.; Doughty, K.N.; Geagan, K.; Jenkins, D.A.; Gardner, C.D. Perspective: The Public Health Case for Modernizing the Definition of Protein Quality. Adv. Nutr. 2019, 10, 755–764.

- Derbyshire, E. Food-Based Dietary Guidelines and Protein Quality Definitions-Time to Move Forward and Encompass Mycoprotein? Foods 2022, 11, 647.

- Salter, A.M.; Lopez-Viso, C. Role of novel protein sources in sustainably meeting future global requirements. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2021, 80, 186–194.

- Mariotti, F.; Gardner, C.D. Dietary Protein and Amino Acids in Vegetarian Diets-A Review. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2661.

- Higgs, J.; Styles, K.; Carughi, A.; Roussell, M.A.; Bellisle, F.; Elsner, W.; Li, Z. Plant-based snacking: Research and practical applications of pistachios for health benefits. J. Nutr. Sci. 2021, 10, e87.

- Yuan, W.; Zheng, B.; Li, T.; Liu, R.H. Quantification of Phytochemicals, Cellular Antioxidant Activities and Antiproliferative Activities of Raw and Roasted American Pistachios (Pistacia vera L.). Nutrients 2022, 14, 2.

- Mateos, R.; Salvador, M.D.; Fregapane, G.; Goya, L. Why Should Pistachio Be a Regular Food in Our Diet? Nutrients 2022, 14, 3207.

- Mandalari, G.; Barreca, D.; Gervasi, T.; Roussell, M.A.; Klein, B.; Feeney, M.J.; Carughi, A. Pistachio Nuts (Pistacia vera L.): Production, Nutrients, Bioactives and Novel Health Effects. Plants 2021, 11, 18.

- EC. Regulation (EC) No 1924/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 December 2006 on Nutrition and Health Claims Made on Foods. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/en/ALL/?uri=CELEX%3A32006R1924 (accessed on 7 November 2022).

- Liu, Y.; Blumberg, J.B.; Chen, C.Y. Quantification and bioaccessibility of california pistachio bioactives. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 1550–1556.

- Paterniti, I.; Impellizzeri, D.; Cordaro, M.; Siracusa, R.; Bisignano, C.; Gugliandolo, E.; Carughi, A.; Esposito, E.; Mandalari, G.; Cuzzocrea, S. The Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidant Potential of Pistachios (Pistacia vera L.) In Vitro and In Vivo. Nutrients 2017, 9, 915.

- Dreher, M.L. Pistachio nuts: Composition and potential health benefits. Nutr. Rev. 2012, 70, 234–240.

- Rock, C.L.; Zunshine, E.; Nguyen, H.T.; Perez, A.O.; Zoumas, C.; Pakiz, B.; White, M.M. Effects of Pistachio Consumption in a Behavioral Weight Loss Intervention on Weight Change, Cardiometabolic Factors, and Dietary Intake. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2155.

- Gulati, S.; Misra, A.; Pandey, R.M.; Bhatt, S.P.; Saluja, S. Effects of pistachio nuts on body composition, metabolic, inflammatory and oxidative stress parameters in Asian Indians with metabolic syndrome: A 24-wk, randomized control trial. Nutrition 2014, 30, 192–197.

- Wang, X.; Li, Z.; Liu, Y.; Lv, X.; Yang, W. Effects of pistachios on body weight in Chinese subjects with metabolic syndrome. Nutr. J. 2012, 11, 20.

- Li, Z.; Song, R.; Nguyen, C.; Zerlin, A.; Karp, H.; Naowamondhol, K.; Thames, G.; Gao, K.; Li, L.; Tseng, C.H.; et al. Pistachio nuts reduce triglycerides and body weight by comparison to refined carbohydrate snack in obese subjects on a 12-week weight loss program. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2010, 29, 198–203.

- Fantino, M.; Bichard, C.; Mistretta, F.; Bellisle, F. Daily consumption of pistachios over 12 weeks improves dietary profile without increasing body weight in healthy women: A randomized controlled intervention. Appetite 2020, 144, 104483.

- Carughi, A.; Bellisle, F.; Dougkas, A.; Giboreau, A.; Feeney, M.J.; Higgs, J. A Randomized Controlled Pilot Study to Assess Effects of a Daily Pistachio (Pistacia vera) Afternoon Snack on Next-Meal Energy Intake, Satiety, and Anthropometry in French Women. Nutrients 2019, 11, 767.

- Bellisle, F.; Fantino, M.; Feeney, M.J.; Higgs, J.; Carughi, A. Daily Consumption of Pistachios over 12 Weeks Improves Nutrient Intake, Induces Energy Compensation, and Has No Effect on Body Weight or Composition in Healthy Women (P08-002-19). Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2019, 3, 2064.

- Esmaeili Nadimi, A.; Ahmadi, Z.; Falahati-Pour, S.K.; Mohamadi, M.; Nazari, A.; Hassanshahi, G.; Ekramzadeh, M. Physicochemical properties and health benefits of pistachio nuts. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 2020, 90, 564–574.

- Hernandez-Alonso, P.; Salas-Salvado, J.; Baldrich-Mora, M.; Juanola-Falgarona, M.; Bullo, M. Beneficial effect of pistachio consumption on glucose metabolism, insulin resistance, inflammation, and related metabolic risk markers: A randomized clinical trial. Diabetes Care 2014, 37, 3098–3105.

- Parham, M.; Heidari, S.; Khorramirad, A.; Hozoori, M.; Hosseinzadeh, F.; Bakhtyari, L.; Vafaeimanesh, J. Effects of pistachio nut supplementation on blood glucose in patients with type 2 diabetes: A randomized crossover trial. Rev. Diabet. Stud. 2014, 11, 190–196.

- Kendall, C.W.; Josse, A.R.; Esfahani, A.; Jenkins, D.J. The impact of pistachio intake alone or in combination with high-carbohydrate foods on post-prandial glycemia. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 65, 696–702.

- Kendall, C.W.; West, S.G.; Augustin, L.S.; Esfahani, A.; Vidgen, E.; Bashyam, B.; Sauder, K.A.; Campbell, J.; Chiavaroli, L.; Jenkins, A.L.; et al. Acute effects of pistachio consumption on glucose and insulin, satiety hormones and endothelial function in the metabolic syndrome. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 68, 370–375.

- Jenkins, D.J.; Kendall, C.W.; Banach, M.S.; Srichaikul, K.; Vidgen, E.; Mitchell, S.; Parker, T.; Nishi, S.; Bashyam, B.; de Souza, R.; et al. Nuts as a replacement for carbohydrates in the diabetic diet. Diabetes Care 2011, 34, 1706–1711.

- Jenkins, D.J.A.; Kendall, C.W.C.; Lamarche, B.; Banach, M.S.; Srichaikul, K.; Vidgen, E.; Mitchell, S.; Parker, T.; Nishi, S.; Bashyam, B.; et al. Nuts as a replacement for carbohydrates in the diabetic diet: A reanalysis of a randomised controlled trial. Diabetologia 2018, 61, 1734–1747.

- Assaf-Balut, C.; Garcia de la Torre, N.; Duran, A.; Fuentes, M.; Bordiu, E.; Del Valle, L.; Familiar, C.; Ortola, A.; Jimenez, I.; Herraiz, M.A.; et al. A Mediterranean diet with additional extra virgin olive oil and pistachios reduces the incidence of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM): A randomized controlled trial: The St. Carlos GDM prevention study. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0185873.

- de la Torre, N.G.; Assaf-Balut, C.; Jimenez Varas, I.; Del Valle, L.; Duran, A.; Fuentes, M.; Del Prado, N.; Bordiu, E.; Valerio, J.J.; Herraiz, M.A.; et al. Effectiveness of Following Mediterranean Diet Recommendations in the Real World in the Incidence of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus (GDM) and Adverse Maternal-Foetal Outcomes: A Prospective, Universal, Interventional Study with a Single Group. The St Carlos Study. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1210.

- Assaf-Balut, C.; Garcia de la Torre, N.; Duran, A.; Fuentes, M.; Bordiu, E.; Del Valle, L.; Familiar, C.; Valerio, J.; Jimenez, I.; Herraiz, M.A.; et al. A Mediterranean Diet with an Enhanced Consumption of Extra Virgin Olive Oil and Pistachios Improves Pregnancy Outcomes in Women Without Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: A Sub-Analysis of the St. Carlos Gestational Diabetes Mellitus Prevention Study. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2019, 74, 69–79.

- Feng, X.; Liu, H.; Li, Z.; Carughi, A.; Ge, S. Acute Effect of Pistachio Intake on Postprandial Glycemic and Gut Hormone Responses in Women With Gestational Diabetes or Gestational Impaired Glucose Tolerance: A Randomized, Controlled, Crossover Study. Front. Nutr. 2019, 6, 186.

- Canudas, S.; Hernandez-Alonso, P.; Galie, S.; Muralidharan, J.; Morell-Azanza, L.; Zalba, G.; Garcia-Gavilan, J.; Marti, A.; Salas-Salvado, J.; Bullo, M. Pistachio consumption modulates DNA oxidation and genes related to telomere maintenance: A crossover randomized clinical trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 109, 1738–1745.

- Hernandez-Alonso, P.; Giardina, S.; Salas-Salvado, J.; Arcelin, P.; Bullo, M. Chronic pistachio intake modulates circulating microRNAs related to glucose metabolism and insulin resistance in prediabetic subjects. Eur. J. Nutr. 2017, 56, 2181–2191.

- Brown, D. FDA considers health claim for nuts. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2003, 103, 426.

- Becerra-Tomas, N.; Paz-Graniel, I.; Kendall, C.W.C.; Kahleova, H.; Rahelic, D.; Sievenpiper, J.L.; Salas-Salvado, J. Nut consumption and incidence of cardiovascular diseases and cardiovascular disease mortality: A meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Nutr. Rev. 2019, 77, 691–709.

- Ghanavati, M.; Rahmani, J.; Clark, C.C.T.; Hosseinabadi, S.M.; Rahimlou, M. Pistachios and cardiometabolic risk factors: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. Complement. Ther. Med. 2020, 52, 102513.

- Sauder, K.A.; McCrea, C.E.; Ulbrecht, J.S.; Kris-Etherton, P.M.; West, S.G. Pistachio nut consumption modifies systemic hemodynamics, increases heart rate variability, and reduces ambulatory blood pressure in well-controlled type 2 diabetes: A randomized trial. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2014, 3, e000873.

- Sheridan, M.J.; Cooper, J.N.; Erario, M.; Cheifetz, C.E. Pistachio nut consumption and serum lipid levels. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2007, 26, 141–148.

- Ros, E.; Singh, A.; O’Keefe, J.H. Nuts: Natural Pleiotropic Nutraceuticals. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3269.

- Collaborators, G.B.D.D. Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2019, 393, 1958–1972.

- Trautwein, E.A.; McKay, S. The Role of Specific Components of a Plant-Based Diet in Management of Dyslipidemia and the Impact on Cardiovascular Risk. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2671.

- Fadelu, T.; Zhang, S.; Niedzwiecki, D.; Ye, X.; Saltz, L.B.; Mayer, R.J.; Mowat, R.B.; Whittom, R.; Hantel, A.; Benson, A.B.; et al. Nut Consumption and Survival in Patients With Stage III Colon Cancer: Results From CALGB 89803 (Alliance). J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 1112–1120.

- Yang, M.; Hu, F.B.; Giovannucci, E.L.; Stampfer, M.J.; Willett, W.C.; Fuchs, C.S.; Wu, K.; Bao, Y. Nut consumption and risk of colorectal cancer in women. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 70, 333–337.

- Nieuwenhuis, L.; van den Brandt, P.A. Total Nut, Tree Nut, Peanut, and Peanut Butter Consumption and the Risk of Pancreatic Cancer in the Netherlands Cohort Study. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2018, 27, 274–284.

- Bao, Y.; Hu, F.B.; Giovannucci, E.L.; Wolpin, B.M.; Stampfer, M.J.; Willett, W.C.; Fuchs, C.S. Nut consumption and risk of pancreatic cancer in women. Br. J. Cancer 2013, 109, 2911–2916.

- Naghshi, S.; Sadeghian, M.; Nasiri, M.; Mobarak, S.; Asadi, M.; Sadeghi, O. Association of Total Nut, Tree Nut, Peanut, and Peanut Butter Consumption with Cancer Incidence and Mortality: A Comprehensive Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Adv. Nutr. 2021, 12, 793–808.

- Bao, Y.; Han, J.; Hu, F.B.; Giovannucci, E.L.; Stampfer, M.J.; Willett, W.C.; Fuchs, C.S. Association of nut consumption with total and cause-specific mortality. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 2001–2011.

- van den Brandt, P.A.; Schouten, L.J. Relationship of tree nut, peanut and peanut butter intake with total and cause-specific mortality: A cohort study and meta-analysis. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2015, 44, 1038–1049.

- Glei, M.; Ludwig, D.; Lamberty, J.; Fischer, S.; Lorkowski, S.; Schlormann, W. Chemopreventive Potential of Raw and Roasted Pistachios Regarding Colon Carcinogenesis. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1368.

- Lim, S.J.; Kwon, H.C.; Shin, D.M.; Choi, Y.J.; Han, S.G.; Kim, Y.J.; Han, S.G. Apoptosis-Inducing Effects of Short-Chain Fatty Acids-Rich Fermented Pistachio Milk in Human Colon Carcinoma Cells. Foods 2023, 12, 189.

- Haider, S.; Madiha, S.; Batool, Z. Amelioration of motor and non-motor deficits and increased striatal APoE levels highlight the beneficial role of pistachio supplementation in rotenone-induced rat model of PD. Metab. Brain Dis. 2020, 35, 1189–1200.

- Singh, S.; Dharamveer; Kulshreshtha, M. Pharmacological Approach of Pistacia Vera Fruit to Assess Learning and Memory Potential in Chemically-Induced Memory Impairment in Mice. Cent. Nerv. Syst. Agents Med. Chem. 2019, 19, 125–132.

- Hakimizadeh, S.; Fatemi, I.M.A. The effect of hydroalcoholic extract of pistachio on anxiety and working memory in ovariectomized female rats. Pist. Health J. 2020, 3, 72–83.

- Rostampour, M.; Hadipour, E.; Oryan, S.; Soltani, B.; Saadat, F. Anxiolytic-like effect of hydroalcoholic extract of ripe pistachio hulls in adult female Wistar rats and its possible mechanisms. Res. Pharm. Sci. 2016, 11, 454–460.

- Ukhanova, M.; Wang, X.; Baer, D.J.; Novotny, J.A.; Fredborg, M.; Mai, V. Effects of almond and pistachio consumption on gut microbiota composition in a randomised cross-over human feeding study. Br. J. Nutr. 2014, 111, 2146–2152.

- Yanni, A.E.; Mitropoulou, G.; Prapa, I.; Agrogiannis, G.; Kostomitsopoulos, N.; Bezirtzoglou, E.; Kourkoutas, Y.; Karathanos, V.T. Functional modulation of gut microbiota in diabetic rats following dietary intervention with pistachio nuts (Pistacia vera L.). Metabol. Open 2020, 7, 100040.

- Hernandez-Alonso, P.; Canueto, D.; Giardina, S.; Salas-Salvado, J.; Canellas, N.; Correig, X.; Bullo, M. Effect of pistachio consumption on the modulation of urinary gut microbiota-related metabolites in prediabetic subjects. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2017, 45, 48–53.

- Yang, J.; Lee, R.; Schulz, Z.; Hsu, A.; Pai, J.; Yang, S.; Henning, S.M.; Huang, J.; Jacobs, J.P.; Heber, D.; et al. Mixed Nuts as Healthy Snacks: Effect on Tryptophan Metabolism and Cardiovascular Risk Factors. Nutrients 2023, 15, 569.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!