Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Chemistry, Organic

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) is an essential signaling gas within the cell, and its endogenous levels are correlated with various health diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease, diabetes, Down’s syndrome, and cardiovascular disease. Because it plays such diverse biological functions, being able to detect H2S quickly and accurately in vivo is an area of heightened scientific interest.

- H2S sensor

- cyanine dye synthesis

- UV/Vis spectroscopy

1. Introduction

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) is the third most important endogenous signal gas that cells use [1,2], after carbon monoxide and nitric oxide. It mediates multiple physiological and pathological processes [3,4]. While crucial to normal biological function, H2S can prove an extremely toxic gas at higher concentrations. Some basic physicochemical and thermodynamic properties of H2S are listed in Table 1 [5].

Table 1. Basic physicochemical and thermodynamic properties of H2S.

| Properties | Data |

|---|---|

| Dipole moment | 0.97 D |

| Solubility (in H2O) | 110 mM/atm, 25 °C |

| 210 mM/atm, 0 °C | |

| Boiling temperature | −60.2 °C |

| Density (25 °C, 1 atm) | 1.36 kg/m3 |

| IR | ν1 2525, 2536 cm−1 |

| ν2 1169, 1184, 1189 cm−1 | |

| ν3 2548 cm−1 | |

| 1H-NMR | 0.52 ppm |

| pK1 | 6.98 |

| pK2 | >17 at 25 °C |

| λmax (HS−) | 230 nm |

| ε | 8 × 103 M−1·cm−1 |

| Henry’s law coefficient (298 K) | 0.087135 mol solute/mol water atom |

| Detection threshold by human nose | 0.02–0.03 ppm |

| Lethal dose | >500 ppm |

| ΔfG° (H2S) | −28 kJ/mol |

| ΔfG° (HS−) | +12 kJ/mol |

| ΔfG° (S2−) | +86 kJ/mol |

| E°′ (S•−, H+/HS−) | +0.91 V |

| E°′ (HS2−, H+/2HS−) | −0.23 V |

A simple molecule, H2S is a marker of some of society’s most prevalent maladies. Cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and Down’s syndrome have all been associated with an increased level of H2S [6]. It is known to regulate myriad biological functions in vivo; oxidative stress, insulin signaling, and cell growth and death are all mediated by this species [7,8]. Energy available to the cell can also be affected by levels of H2S because it is involved in the inhibition of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) [9,10,11,12,13].

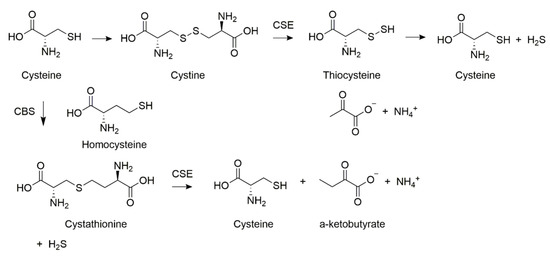

Biosynthesis of H2S in mammals is carried out by the enzymes cystathionine β-synthase (CBS), 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfotransferase (3-MST), and cystathionine γ-lyase (CSE) [14]. The endogenous pathways are laid out in Scheme 1 [15]. Homocysteine acts as the substrate for CBS, with H2S and cystathionine being liberated. The second mode involves a “desulfurization” reaction, whereby sulfur is cleaved from cysteine directly without its oxidation. Furthermore, it has been reported that the activities of these two enzymes in different cells and tissues are correlated to several health disorders [16,17,18]. For these reasons, H2S has become an important medium in the detection of disease [19,20,21].

Scheme 1. Endogenous hydrogen sulfide synthesizing pathways.

Traditional methods of H2S detection, such as electrochemical analysis and gas chromatography, require a sample of living cells from target tissues [22,23]. However, since H2S can exist at levels as low as 30 μM in human blood, such methods are inadequate for detecting the analyte in the blood [24]. With these limitations in mind, the discovery of highly sensitive and selective detection methods for H2S is of peak interest [25,26,27,28,29,30]. Traditional methods also present the inherent drawbacks of trauma from conducting biopsies, inconsistent concentrations of the analyte within the target tissue, and an overall more tedious process. To improve results, various probes have been synthesized for the selective and specific detection of H2S [31,32,33].

Recent studies have shown the visible and NIR probes to be favorable due to their high-yield synthesis, modular structures, low cytotoxicity, and high sensitivity and selectivity [34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46]. Importantly, they work in real time and require nothing but an injection [47]. In the past few years, much work has been put into shortening response times, reducing Stokes shifts, and increasing the fluorescence wavelengths of these compounds [48,49,50,51]. Such findings would provide healthcare workers with new tools to prevent, detect, and treat various diseases.

2. Different Mechanisms of H2S Detection

2.1. Nucleophilic Addition to the Conjugated System for H2S Detection

Under the physiological condition of pH 7.6, H2S was deprotonated to HS−. This species was then able to be added to the conjugated system by way of nucleophilic attack onto the electrophilic center of the probe. In this way, cyanine dyes were able to detect H2S. Such a mechanism has four different modes of signal transduction. These include intramolecular charge transfer (ICT) [61,62,63], twisted intramolecular charge transfer [64,65,66] (TICT), fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) [67,68,69], and photoinduced electron transfer (PET) [72,73,74]. Each of these processes involves the transfer of energy within the probe in the presence of the analyte. These mechanisms are discussed individually under the banner of H2S detection by way of nucleophilic addition to a conjugated system.

2.1.1. Intramolecular Charge Transfer (ICT)

This is the process of converting light energy into chemical energy. An example is photosynthesis, where plants use sunlight to carry out key charge separation processes in the production of food. The ICT process depends on the relationship between intensities of the donor and acceptor in the system. The donor resides at the HOMO energy level, and the acceptor resides at the LUMO. Moreover, the energy gap between the two can serve to insulate or conduct depending on the circumstances, which determines the electronic coupling degree between the two orbitals [61,62,63].

Synthesis and Mechanism of H2S Probes Based on ICT

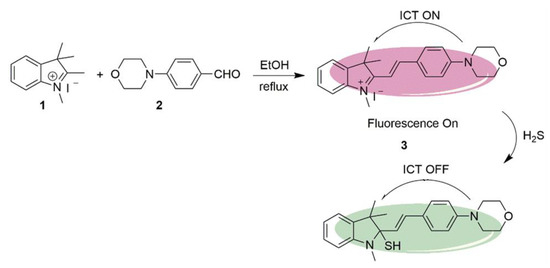

An example of a H2S probe performing on the basis of ICT is the morpholinostyryl probe 3, as illustrated in Scheme 2. It was synthesized by Li et al. following the reaction of indolium salt 1 with aldehyde 2. Under reflux in ethanol, a yield of 70% was achieved. The probe behaves as a switch, with fluorescence turning on and off in the absence and presence of H2S, respectively. This occurs because H2S, behaving as the nucleophile, attacks the indolium moiety to break conjugation. The result was a loss of fluorescence in the presence of the H2S at levels as low as 30 μM [61].

Scheme 2. Synthetic route and detection mechanism of H2S probe 3.

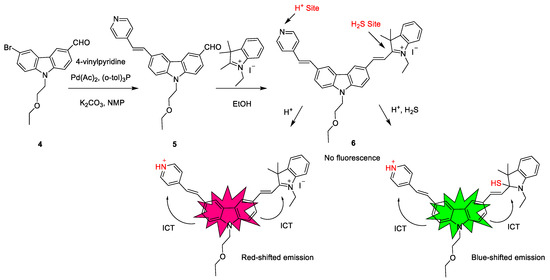

In the previous example of a H2S probe, the detection is indicated by a loss of fluorescence. A different probe was synthesized by Yong Liu et al. to have a hypsochromic shift upon binding with the H2S analyte. Scheme 3 shows the production of probe 6 following a two-step reaction. First, the bromine of compound 4 is substituted with 4-vinylpyridine under basic conditions using a Pd(Ac)2 catalyst to yield compound 5. Next, the conjugated system is extended following a Vilsmeier–Haack coupling with an indolium salt. The resulting probe 6 contains two separate sites where the fluorescence wavelength can be altered. Protonation can occur at the pyridine moiety to result in a bathochromic shift, and the indolium moiety can undergo nucleophilic attack in the presence of H2S to give a hypsochromic shift. As it is able to distinguish between H2S present in acidic versus nonacidic conditions, probe 6 can be useful in detecting the H2S analyte in different parts of the body. This is possible because the fluorescence wavelength can easily be measured by spectroscopy, and whichever shift is observed can indicate the environment in which the analyte was present. For instance, tumors are known to be more acidic than the surrounding healthy tissue while blood is normally slightly alkaline [62].

Scheme 3. Synthetic route and detection mechanism of probe 6.

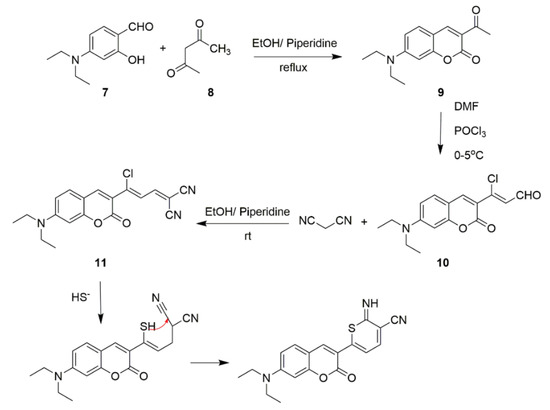

A novel on/off NIR fluorescent probe was developed by Fengzao Chen et al. which is unique in that it can detect H2S simultaneously by cyclization to form the six-member ring. Its synthesis and ICT mechanism are laid out in Scheme 4, involving three steps before being able to bind to H2S. The aldehyde derivative 7 and the 1,3-dicarbonyl compound 8 are refluxed under basic conditions to yield coumarin derivative 9. The resulting ketone group of 9 is formylated via a Vilsmeier–Haack coupling reaction with DMF in the presence of POCl3 to yield compound 10. Subsequent condensation with malononitrile produced compound 11 at a yield of 60%. This step is carried out at room temperature using EtOH and piperidine as solvents, and it results in the conjugated system being lengthened, as well as the addition of the strongly electron-donating cyano groups. This final product is then able to detect H2S under physiological conditions. The deprotonated species HS− substitutes the chloride to give a thiol which then undergoes a proton transfer with one of the cyano groups. A six-membered ring is formed, and this can be detected by the shift in fluorescence wavelength [63].

Scheme 4. Synthetic route and detection mechanism of H2S probe 11.

Optical Properties of ICT H2S Probes

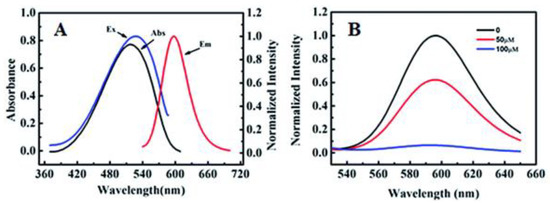

Referring to the on/off H2S probe synthesized by Li et al. in Scheme 2, probe 3 was shown to absorb light at a wavelength of 520 nm and fluoresce at 596 nm, as shown in Figure 1A. Its fluorescence intensity was then measured at 600 nm in the presence of H2S at varying concentrations. Figure 1B reveals that the signal of probe 3 was strongest with the analyte absent, but its signal was unobservable at a concentration of 100 μM of H2S. These results prove that probe 3 is a useful H2S sensor [61].

Figure 1. (A) Absorption and fluorescence spectra of probe 3. (B) Fluorescence spectra of probe 3 (10 μM) in H2S at varying concentrations.

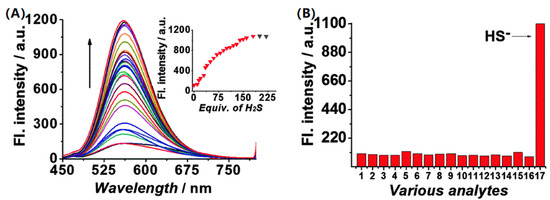

H2S probe 6 reported by Yong Liu et al. (Scheme 3), which displayed a bathochromic shift upon detection of the H2S analyte, was also found to exhibit spectral changes at varying pH of H2S. The absorption and fluorescence spectra of probe 6 at different pH values are shown in Figure 2A,B, respectively. Furthermore, probe 6 is highly sensitive to H2S under acidic conditions (Figure 2A). As presented in Figure 2B, probe 6 has good selectivity of H2S over various other sulfur-containing molecules such as SO42−, S2O32−, and cysteine [62].

Figure 2. (A) Fluorescence spectra of probe 6 (10 μM) in pH 4.4 PBS buffer solution (containing 5% DMSO) with the addition of H2S. (B) Fluorescence responses of probe 6 at 405 nm in the presence of: 1. Probe 6; 2, Cl−; 3, K+; 4, Ca2+; 5, Mg2+; 6, GSH; 7, H2O2; 8, Hcy; 9, HSO3−; 10, I−; 11; Cys; 12, NO2−; 13, S2O32−; 14, SO32−; 15, SO42−; 16, Zn2+; 17, HS−.

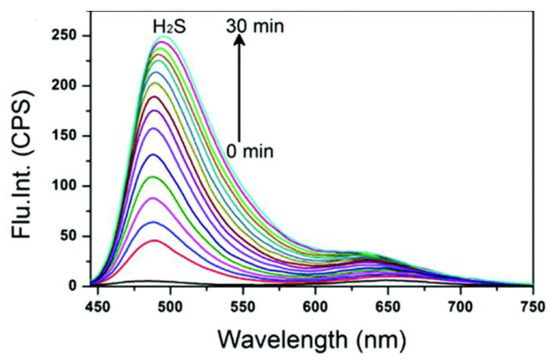

The third H2S probe operating on the ICT principle, probe 11 (Scheme 4), was also studied to undergo changes to its fluorescence spectra at 490 nm by Fengzao Chen et al., as shown in Figure 3. Intensity of fluorescence took 30 min to reach a plateau in the presence of H2S, at which point there was only marginal increase in signal strength with time [63].

Figure 3. Time-dependent fluorescence spectral changes of probe 11.

The Application of H2S Probes Based on ICT

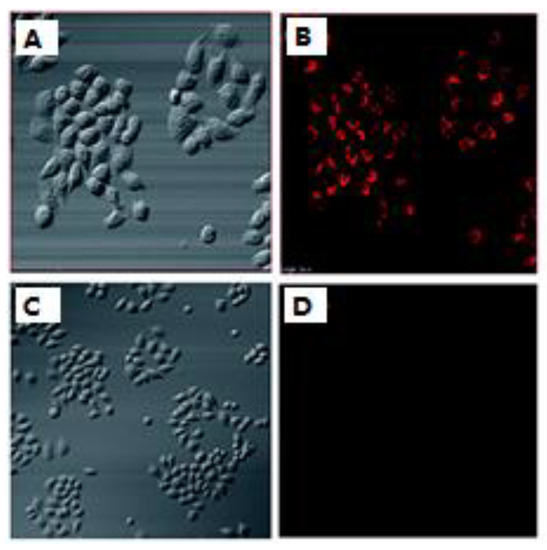

The immortalized cells of Henrietta Lacks, who died of advanced cancer in 1951, were used to further bolster the ability of probe 3 (Scheme 2) to detect H2S in living cells. This sensor penetrated the cell membrane as shown by the contrast between bright-field and fluorescence images of cells incubated with probe 3 (Figure 4A,B). Overlaying the bright-field and fluorescence images of cells treated with probe 3 verified this claim. Conversely, there was no visible fluorescence upon addition of H2S to the culture (Figure 4C,D). These images indicate that probe 3 could effectively penetrate the membrane and was selective toward H2S in living cells [61].

Figure 4. (A) Bright-field images of cells treated with probe 3. (B) Bright-field images of cells preincubated with probe 3 and NaHS. (B,D) are fluorescence images of (A,C), respectively.

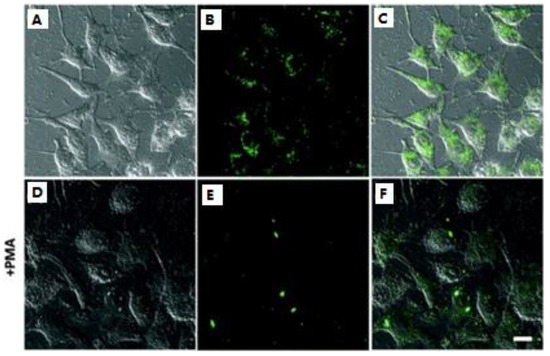

Probe 6 (Scheme 3) was used to detect endogenous H2S in the lysosomes of A549 cells. To highlight the probe’s ability to detect H2S, an assay was performed both with and without the presence of PMS (12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol 13-acetate, 4β,9α,12β,13α,20-pentahydroxytiglia-1,6-dien-3-one 12-tetradecanoate 13-acetate), which was used to reduce endogenous H2S levels. Figure 5 illustrates that probe 6 did indeed detect the analyte within the lysosomes of the A549 cells (A–C), but the signal was reduced upon the addition of the H2S inhibitor, PMA (D–F). The addition of the inhibitor serves to prove the probe’s selectivity toward H2S and not simply any sulfur-containing analyte. The study confirms the ability of probe 6 to detect endogenous H2S in the cell lysosome under the green channel [62].

Figure 5. Fluorescence imaging of the endogenous H2S in the lysosomes: (A–C) the cells incubated with 5.0 μM probe 6 only; (D–F) the cells pretreated with PMA and then incubated with probe 6. (A,D) bright-field images; (B,E) fluorescence; (C,F) merged.

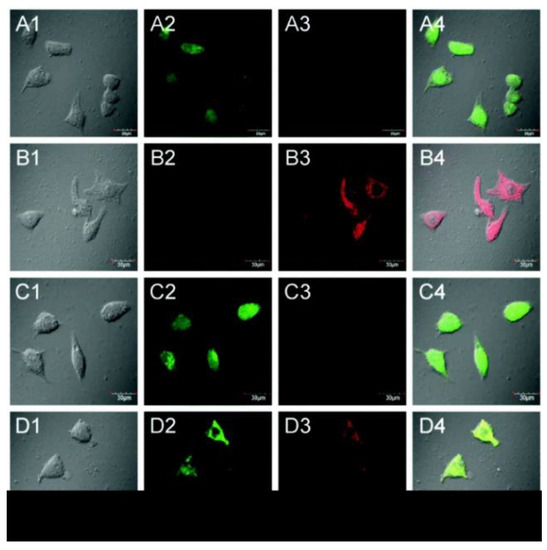

Probe 11 (Scheme 4) was used to detect H2S levels in MCF-7 cells. As shown in Figure 6, a strong fluorescence signal was observed in the green channel from 470–530 nm with H2S present (Figure 6(D2)), but hardly any was seen in the red channel from 620–680 nm (Figure 6(D3)). Upon addition of probe 11 following treatment with the H2S inhibitor NEM, only red-channel signals were seen (Figure 6(B4)). This means that, without H2S, probe 11 would show red channel signals. In the groups with supplemental H2S in addition to the inhibitor, the phenomenon was quite different; all others were only detectable in the green channel (Figure 6C,D). H2S causes a blue shift, and the signal is shown in the green channel. These results proved that probe 11 has use as an effective tool in detecting H2S in MCF-7 cells [63].

Figure 6. (A) Cells incubated with only probe 11; (B) cells were preincubated with NEM and subsequently treated with probe 11; (C) cells pretreated with NEM followed by treatment with probe 11 and GSH; (D) cells pretreated with 0.6 mM NEM followed by probe 11 and then with H2S. Column 1, bright field; column 2, green channel; column 3, red channel; column 4, merged images of columns 1, 2, and 3.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/molecules28031295

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!