Whole-mouth (WMS) saliva is the most-used biofluid in the salivary metabolic analyses. The collection of saliva samples has many advantages because it is non-invasive, painless, and safe without piercing the skin. Saliva is easy to collect without complex equipment and does not require special expertise. Furthermore, the storage of saliva samples is simple and cheap. Saliva contains both endogenous and exogenous metabolites, which can tell us about biological pathways in the oral cavity. However, their role as biomarkers in the diagnostics of oral and systemic diseases is also investigated as reviewed by Hyvärinen et al. [

3]. Saliva allows measuring the levels of metabolites, including nucleic acids, lipids, amino acids, peptides, vitamins, organic acids, thiols, and carbohydrates, representing a useful tool for the detection of biomarkers for various oral diseases and monitoring disease progression. Salivary metabolites are involved in a variety of cellular functions, such as direct regulation of gene expression and they function as the effectors of molecular events that contribute to disease [

4]. A minor part role for salivary metabolites could be as a potential source of systemic biomarkers, however, the main sources of salivary metabolites are productions of oral metabolic pathways, especially produced by micro-organisms [

5,

6].

2. Sources of Salivary Metabolites in Healthy Subjects

Saliva is an oral fluid secreted by the major and minor salivary glands. After entering the oral cavity, it is referred to as mixed or whole saliva, supplemented with many constituents originating from blood, mucosal cells, immune cells, and microorganisms [

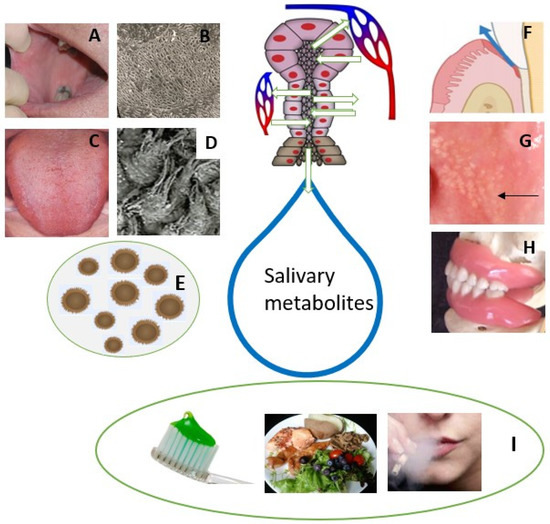

9]. Whole saliva represents the complex mixture of a variety of molecules and hence, it is valuable to use in research. The composition of saliva and oral microbiota differ in healthy subjects most likely due to age, gender, habits, diet, oral hygiene, medication, and different oral niches (prothesis, tooth fillings, tongue disorders, sebaceous glands = Fordyce granules) (

Figure 1).

The oral microbiome is a set of diverse micro-organisms that inhabit different niches of the oral cavity. They, together with salivary defence, play a key role in the oral balance between health and diseases. Oral microbes communicate with oral epithelial cells via Toll-like receptors (TLRs) which plays a key role in the oral immune system producing inflammatory cytokines. Studies using scanning electron microscopy (SEM; Figure 1B) showed no or very few micro-organisms on the buccal mucosal surface. Instead, most of the mucosal microorganisms are located on the dorsal tongue surface (Figure 1C), especially on the surface of rough hyphae of filiform papillae (Figure 1D).

GCF is another oral fluid and an inflammatory exudate derived from the blood vessels of gingival plexus, adjacent to the gingival epithelium. The bacterial degradation product in the GCF promotes the binding of calculus formation subgingivally [

10]. GCF provides ease in collection and sampling of multiple sites of the oral cavity simultaneously due to its close interaction with periodontal cells and bacterial biofilm.

Fordyce granules (FG) are tubule-acinar sebaceous glands (Figure 1G), most often located in the lip and buccal mucosa and are more common in males. The ductus of FG opens into the oral cavity and a lipase-containing secretion is possibly passed into saliva. However, their significance in the salivary metabolic profile is likely to be limited.

Dentures present different niches for the colonization of micro-organisms (

Figure 1H). Candidiasis without any symptoms is a quite common oral disorder in denture wearers. This also indicates dysbiosis of oral microbiota that further changes the salivary metabolic profile in denture-wearing patients. Furthermore, the denture can be colonized by respiratory pathogens, which can even be a risk of respiratory infection [

11]. Individuals with appliances for orthodontic treatment are advised for practice proper oral hygiene. Failure in such practices results in plaque and calculus deposition superimposed with the bacterial degradation product causing gingival and periodontal inflammation. This further raises the possibility of change in salivary metabolite.

3. Salivary Metabolites in Patients with Oral Inflammation

The oral cavity contains a complex array of diverse microorganism that is tightly controlled by their host via metabolic machinery, substrate-specific or salivary secretory products. A mutually beneficial equilibrium exists between the host and oral microbiota until it is disturbed by some external factors [

12]. Several oral disorders, including caries, gingivitis, periodontitis, and oral ulcerations, relate to oral microbiota dysbiosis wherein generation of metabolites can result in inflammation-mediated tissue destruction (

Table 1).

* N = total number of subjects; HC = healthy controls; D = diseased; NM = not mentioned; WS = whole saliva; USWS = unstimulated whole saliva; SWS = stimulated whole saliva; GABA = γ-aminoglutamate.

Caries and periodontitis are the most common oral inflammatory diseases in humans globally. Caries is more common in children and older people while periodontitis is the most common oral disease in the middle-aged population. Therefore, the age of individuals participating in a study may affect the metabolic profile. For example, in a comparative study of caries-related metabolites, a difference was found between adults’ and children’s salivary metabolites [

21,

22].

Both caries and periodontitis are induced by bacterial dysbiosis in the oral cavity. Dental caries results in an imbalance in the microbiota. Most of the microorganisms associated with tooth decay acquire a selective advantage over other species by changing the homeostatic balance of the salivary biofilm. The main source of carbohydrates for caries-causing micro-organisms is consumed food. These carbohydrates usually leave the mouth within about an hour due to saliva’s lubrication effect of the saliva. Of course, this washout is affected by the saliva secretion rate, which means that hyposalivation in patients does not wash their mouth out in the same way as in subjects with normal salivary flow rate [

23]. Microorganisms in the oral biofilm can metabolise dietary carbohydrates to produce organic acids, which will decrease pH and initiate the demineralisation of dental hard tissues, developing caries [

24]. High levels of free amino acids have been linked to increased protein hydrolysis activity by oral bacteria. High proline and glycine levels are the possible result of the hydrolysis of dentin-collagen in caries active individuals [

25]. The high level of lipids on the salivary pellicle of tooth surfaces can inhibit the acid diffusion and accelerates to caries development [

26]. Salivary metabolites produced by bacterial metabolism, including lactate, acetate and n-butyrate have been shown in patient with caries. These metabolites can reduce the pH and increase the porosity of the dental plaque matrix [

27].

Periodontopathogenic bacteria contribute to periodontal diseases. The oral microbes release salivary metabolites as a product of multifactorial interactions between host, oral bacteria, and altered cellular metabolism of the host. The change in the metabolite concentration is correlated with the products of the pathogenic bacterial population. The change in the sub-gingival environment with regard to oxygen tension, redox potential, pH, and availability of host-derived macromolecules has been shown previously. Such changes are responsible in a cause-and-effect way for modulation of the bacterial composition [

14] (

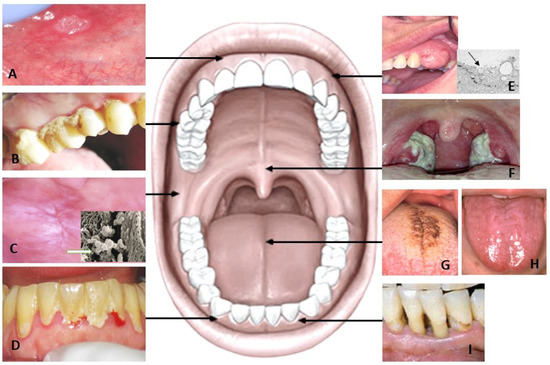

Figure 2). Gingival crevicular fluid (GCF) whose composition is close to that of serum, flows into the oral cavity from periodontal pockets and varies in gingival inflammation [

28]. Some anaerobic periodontal bacteria can produce very short chain fatty acid (SCFAs) metabolites that are released from infection sites into the microenvironment. This can further contribute to the periodontal pathogenesis further through impairment of immune cells or fibroblasts and the epithelial cell functions [

29]. SCFAs, the end-products of bacterial metabolism such as butyrate, caproate, isocaproate, propionate, isovalerate and lactate have been linked to deep periodontal pockets, loss of insertion, bleeding, and inflammation. These metabolites are significantly decreased following periodontal treatment and gradually increases over time, which makes them possible indicators of periodontal disease development and progression [

16].

In recent years, the relationship of periodontitis relationship with systemic diseases as cardiovascular diseases, diabetes mellitus, and problems during pregnancy, rheumatoid arthritis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, pneumonia, obesity, chronic kidney disease, metabolic syndrome and cancer has been amply demonstrated [

30]. Several mechanisms have been proposed, including the transient bacteramia resulting in bacterial colonisation in extra-oral sites, systemic injury by release of free toxins and systemic inflammation triggered by soluble antigens of oral pathogens [

31]. However, controversy exists between different studies due to the heterogeneity in the definitions and identification of periodontitis.

4. Salivary Metabolomics in Oral Mucosal Diseases and Oral Cancer

In the oral cavity, there are many kinds of tissue and it forms a very complex milieu. There are also many diseases in the mouth, of which only the most important are presented.

Oral ulcerations are the most common oral mucosal lesions. Recurrent aphthous stomatitis (RAS) is an inflammatory disorder, which is characterised by recurring and painful ulcers on the surface of the oral mucosa (

Figure 2A). Typically, aphthous ulcers occur in adolescents and young adults, with the majority of patients affected being under 30 years of age and seldom in adults older than 40 years [

32]. Ulcerations associated with aphthous stomatitis (RAU) are thought to represent a dysfunction on the oral immune system [

33,

34] Several studies have reported different etiology factors for RAU including the presence of certain oral microbial communities, immunological factors, endocrinopathies, and psychological and hereditary factors [

35]. The difference in the oxidant/antioxidant status in the blood and saliva of patients with and without RAU has been previously described [

36]. Only one study has been conducted with changes in the metabolite related to aphthous stomatitis [

37]. An imbalance of the tryptophan metabolism and steroid hormone biosynthesis have been shown to be correlated with increased incidence of oral ulcers [

37]. Salivary metabolites have been shown to increase in serotonin, which influences psychological factors including depression and stress in patients with aphthous ulcers.