Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Human NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 (hNQO1) is a multifunctional and antioxidant stress protein whose expression is controlled by the Nrf2 signaling pathway. hNQO1 dysregulation is associated with cancer and neurological disorders. Recent works have shown that its activity is also modulated by different post-translational modifications (PTMs), such as phosphorylation, acetylation and ubiquitination, and these may synergize with naturally-occurring and inactivating polymorphisms and mutations.

- phosphorylation

- acetylation

- ubiquitination

- intracellular degradation

1. Human NQO1: A Stress-Protein Associated with Disease

Human NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 (UniProt ID: P15559) is a soluble, typically cytosolic, dimeric protein at the hub of the antioxidant defense and stabilization of up to 50 different proteins, including p53 and HIF-1α [1][2]. Although hNQO1 has historically been labeled as a cytosolic enzyme, it is likely found in multiple subcellular locations [2][3]. As an enzyme, it catalyzes the two-electron reduction of a wide range of quinones to hydroquinones using NAD(P)H as a coenzyme, displaying negative cooperativity regarding catalysis and FAD binding [4][5][6][7] and also detoxifying superoxide radicals [8].

Recent advances in DNA sequencing technologies are revealing significant genetic variability among human populations [9]. About half of these mutations are of uncertain significance [10], found in only a single individual [11], and are missense mutations (vs. the human consensus genome) [11]. This genetic variability also causes variable responses to pharmacological treatments [12][13][14]. It is partially accessible from databases such as gnomAD (with information of over 140,000 human genomes/exomes; https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/ accessed on 15 December 2022) and more disease-oriented ones such as ClinVar (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/ accessed on 15 December 2022) or dbGaP (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gap/ accessed on 15 December 2022).

NQO1 is highly inducible upon stress through the Nrf2 or Ah pathways [1][8]. The Nrf2 regulatory pathway mediates the delicate balance between oxidative signaling and antioxidant defense, and it is likely that the NQO1 antioxidant properties and its modulation of reduced/oxidized forms of NAD+ play important roles [3][8][15][16][17][18]. The Nrf-2 pathway is associated with multiple human pathologies, including alcohol-induced liver disease, cigarette smoking, cancer and neurodegeneration [18]. The molecular details and physio-pathological implications of Nrf2 signaling have been extensively reviewed in the past [18]. As is essential for this manuscript, it must be noted that alterations in NQO1 activity are also associated with certain diseases linked, to different extents, with oxidative stress, such as cancer, Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease and atherosclerosis [1][8]. Remarkably, certain genetic variations in NQO1 have been associated with cancer development, possibly due to a loss of activity and stability [1][19][20][21][22][23].

2. NQO1: A Simple Dimer with Complex Behavior

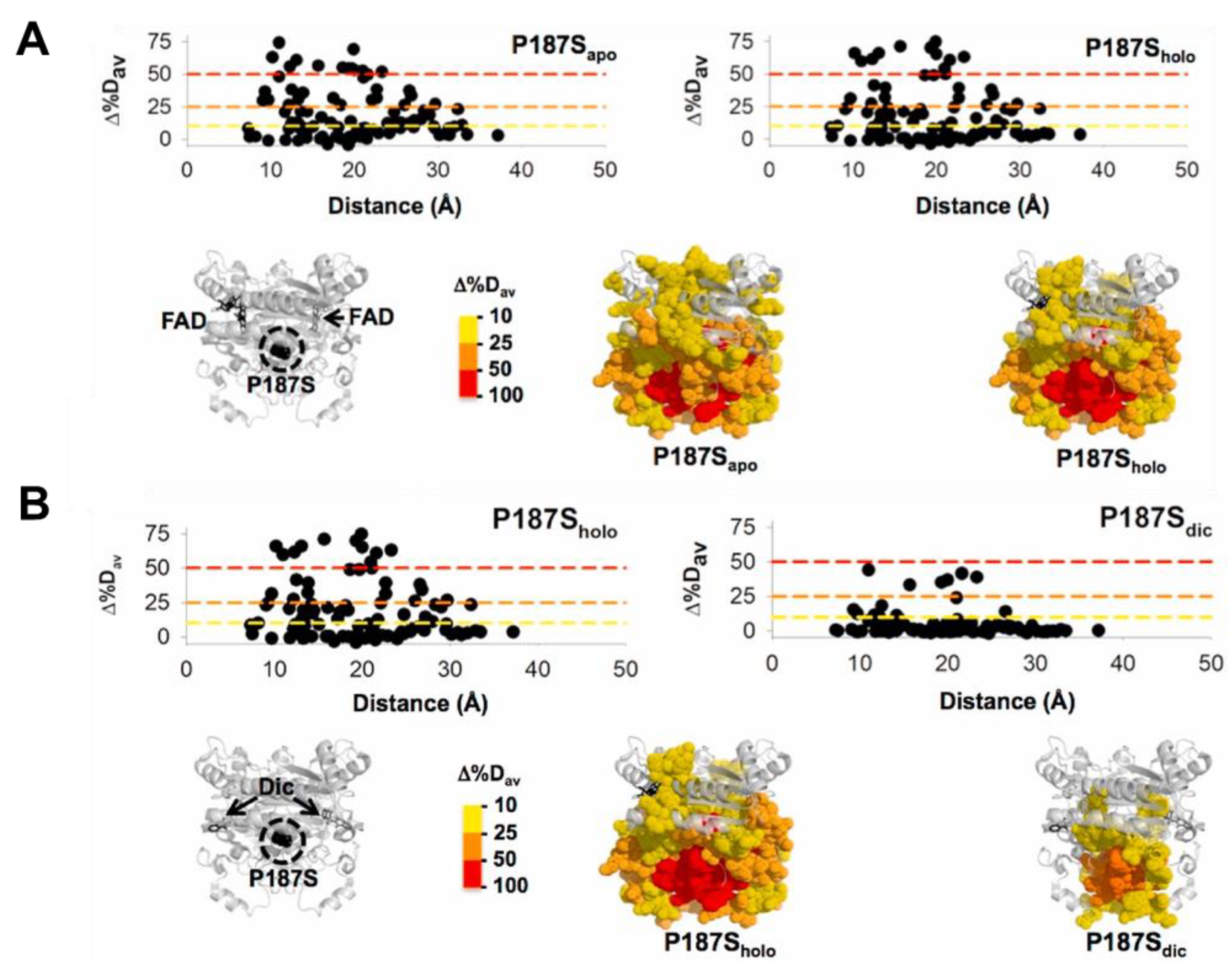

Evolution has likely selected many mammalian proteins as oligomers to allow them to display complex regulatory behaviors. NQO1 seems to be an excellent example. Simply, as a dimer, NQO1 contains two active sites formed upon interaction of the large N-terminal domains (NTD), but requiring the small C-terminal domain (CTD) of the other subunit for efficient catalysis [21][24]. Both active sites, as well as the two domains, communicate in different functional ligation states along its catalytic cycle [4][25]. Detailed titration calorimetry experiments have revealed genuine negative cooperativity for FAD equilibrium binding to the apo-NQO1 protein [5]. In addition, binding of the competitive inhibitor dicoumarol (Dic) in calorimetric and steady-state activity assays also displays, in some instances, a degree of negative binding cooperativity [6][7]. Extensive functional and hydrogen–deuterium exchange (HDX) studies, as well as theoretical calculations, have supported the existence of long-range communication of local perturbations due to single amino acid changes and ligand binding to sites as distant as 30 Å [24][25][26][27][28][29] (Figure 1). This long-range conformational communication likely underlies the cooperative effects described upon ligand binding.

Figure 1. Long-range structural effects due to the cancer-associated P187S polymorphism in different ligation states (apo, no ligand bound; holo, with FAD bound; dic, with FAD and dicoumarol bound). The figure shows the effect of P187S (vs. the WT protein) in different ligation states (A, apo vs. holo; B, holo vs. Dic) considering over 100 protein segments by HDX (Δ%Dav, a semiquantitative parameter calculated from the maximal differences in HDX; a positive value indicates a destabilizing effect) and regarding the distance to the mutated P187 residue.

3. Post-Translational Modifications (PTMs) in hNQO1

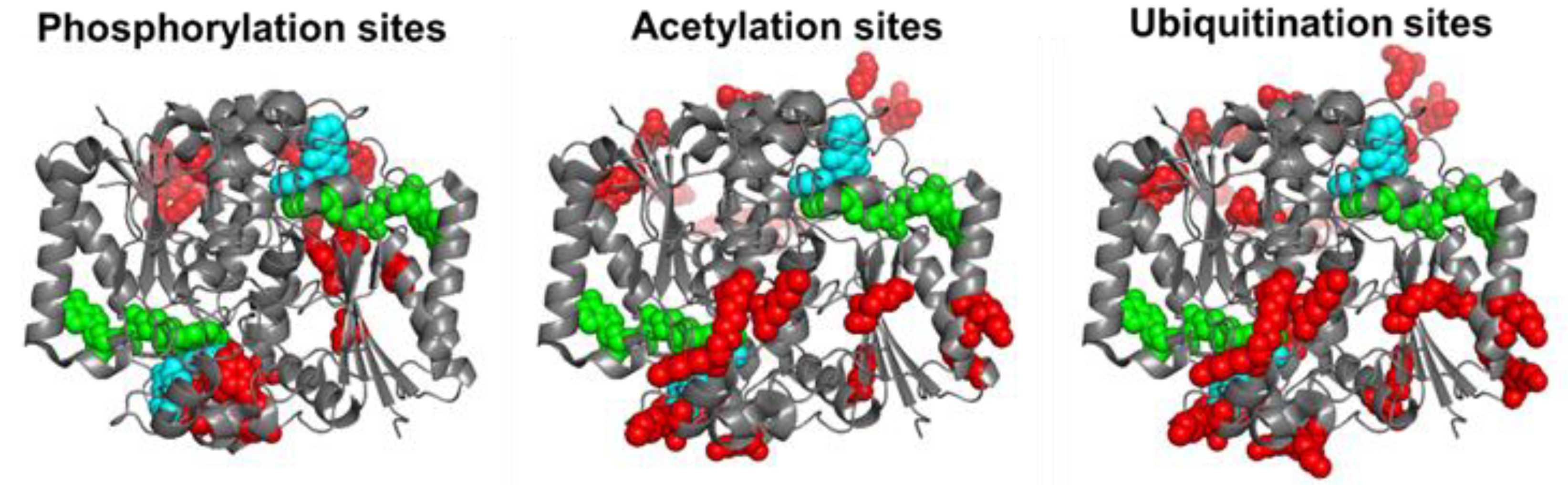

By 11 December 2022, the Phosphosite plus® site (https://www.phosphosite.org/proteinAction.action?id=14721&showAllSites=true accessed on 11 December 2022) contained 12 phosphorylation sites (S13, Y20, S40, Y43, Y68, Y76, S82, Y127, T128, Y129, Y133 and S255), 9 acetylation sites (K31, K59, K61, K77, K90, K209, K210, K251 and K262) and 18 ubiquitination sites (K23, K31, K33, K54, K59, K61, K77, K90, K91, K135, K209, K210, K241, K248, K251, K262 and K271) for hNQO1. As can be seen, these sites are well-spread across the entire protein structure, and in the case of ubiquitination and acetylation, they often overlap (Figure 2). I must note that the functional consequences of only a few of these sites have been characterized in detail. These studies are described and discussed in this section.

Figure 2. Structural location of phosphorylation, acetylation and ubiquitination sites of hNQO1 based on the data compiled in Phosphosite Plus®. Residues in red show those which are modified based on high-throughput analyses. I show the Dic molecules in cyan and the FAD in green. This figure was made based on the structure with PDB code 2F1O.

3.1. Phosphorylation

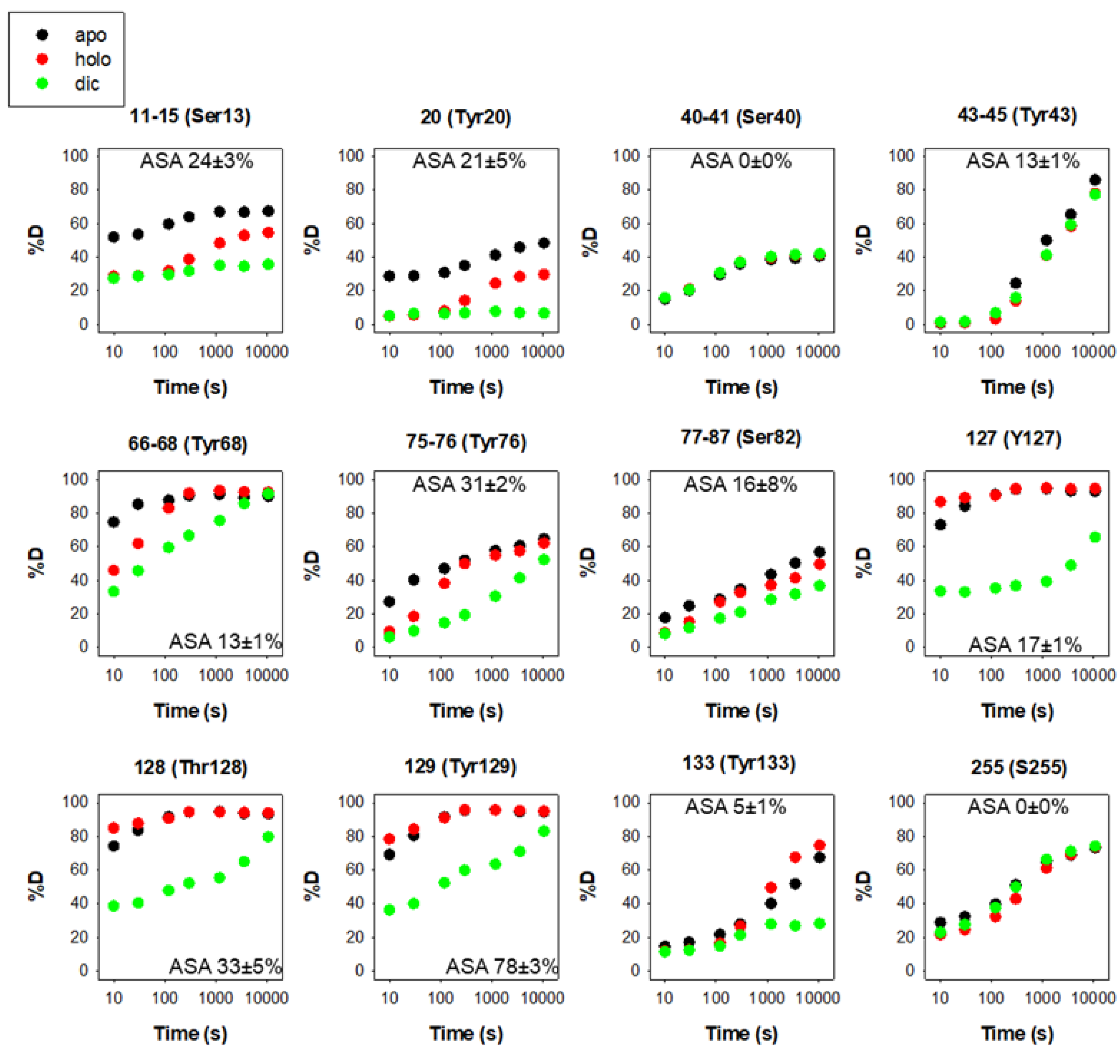

There are 12 reported phosphorylation sites in hNQO1 (Figure 2). It is interesting to note that most of these sites are not highly solvent-exposed, but are located in regions with moderate to low structural stability, which is highly dependent on ligand binding, based on a recent HDX study (Figure 3) [25]. These analyses suggest that phosphorylation might depend strongly on ligand binding and consequent changes in protein dynamics, or might occur cotranslationally.

Figure 3. Structural stability of the phosphorylation sites in hNQO1 in different ligation states (apo, no ligand bound; holo, saturated with FAD; dic, saturated with FAD and dicoumarol). Data show the time-dependence (x-axis) of the peptide backbone hydrogen–deuterium exchange (%D, y-axis) as determined by mass spectrometry. The solvent accessible surface (ASA, %) is indicated in parentheses and calculated using GetArea and the PDB 2F1O as the average ± s.d. from eight monomers.

The functional consequences of phosphorylation at sites S40, S82 and T128 have been addressed recently by the use of phosphomimetic mutations [26][28][30]. The outcomes of these studies have been very revealing, because the functional effects are widely different depending on the site modified. Phosphorylation at S82 causes the strongest effects, with a remarkable decrease in FAD binding affinity, and its local destabilization extends across the hNQO1 structure, affecting the catalytic cycle and intracellular stability [26][28][30]. The effect of phosphorylation at S82 synergizes with that of the polymorphism P187S, leading to an almost 1000-fold decrease in FAD binding affinity [30]. A network of recently diverged electrostatic interactions in the vicinity of S82 has been shown to explain the different response of human and rat NQO1 to phosphorylation at S82. This is due to a single mutation (R80H) that occurred about 20 million years ago during primate speciation [30][31][32]. Phosphorylation at sites S40 and T128 has milder functional effects, affecting enzyme kinetics and structure much more weakly [26]. Importantly, phosphorylation of T128 by AKT is also associated with enhanced ubiquitination by Parkin and subsequent degradation of hNQO1, supporting the notion that phosphorylation, ubiquitination and intracellular stability of hNQO1 might be intertwined [33]. Researchers are currently characterizing phosphomimetic mutations at Y127 and Y129, located in the hNQO1 active site, and the preliminary results support that phosphorylation at Y127 may perturb binding of FAD to the active site of hNQO1, whereas Y129 could be implicated in the conformational heterogeneity likely associated with functional negative cooperativity in the holo-protein (Pacheco-García JL, Martín-García JM, Medina M and Pey AL, unpublished observations).

3.2. Ubiquitination

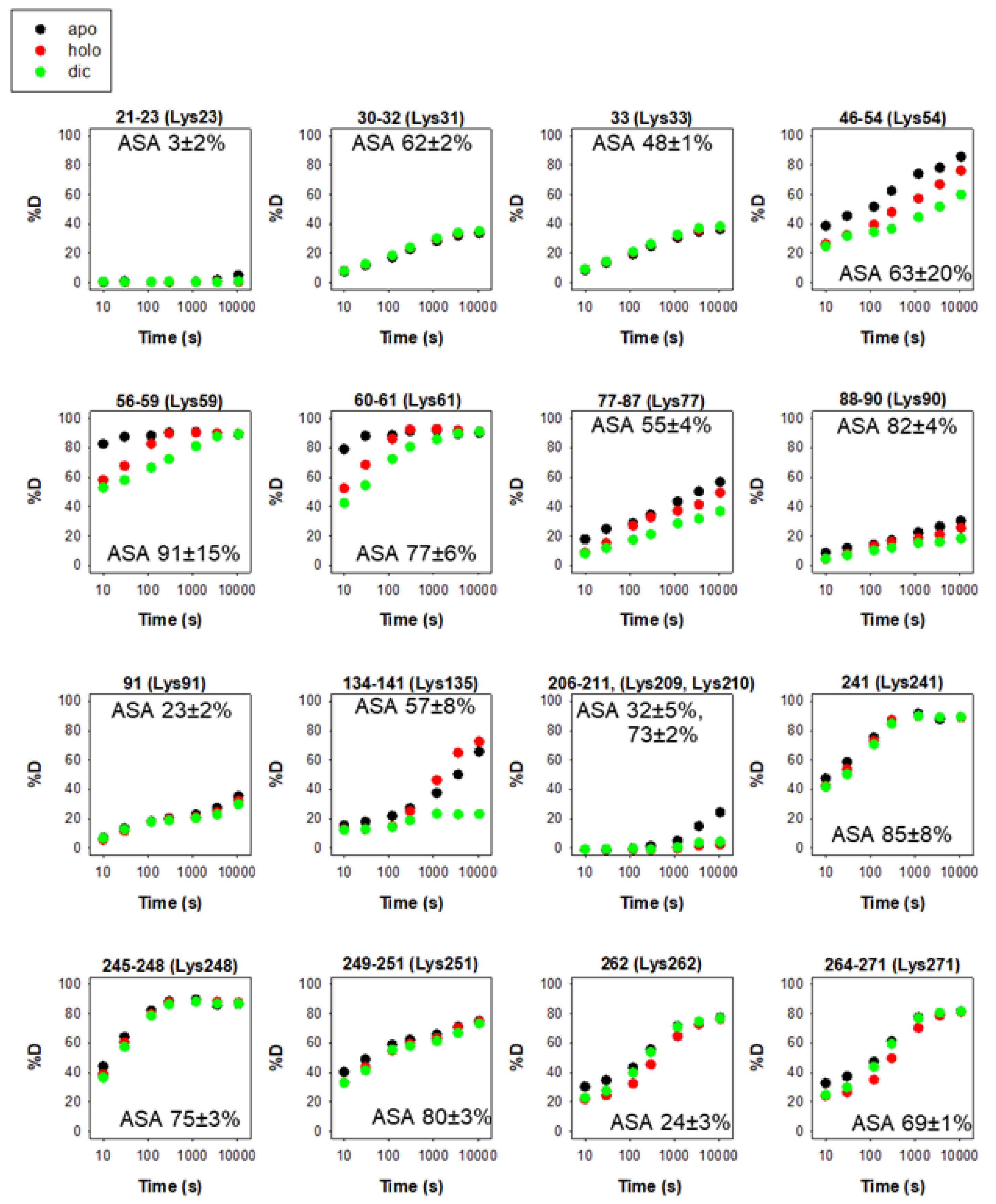

The intracellular stability of WT, and particularly of the polymorphic P187S hNQO1, is tightly associated to their C-terminal dynamics through ubiquitin-dependent proteasomal degradation of its CTD as an initiation site [24][29][34][35]. While this accelerated degradation of P187S might be due to enhanced dynamics of the CTD of the polymorphic variant P187S [24][28][36], it seems that the apo-state (ligand-free) of hNQO1 is particularly suitable for proteasomal degradation upon ubiquitin tagging even in the WT variant [35]. Thus, the sites K241, K248, K251, K262 and K271 are likely responsible for most ubiquitin-dependent degradation of hNQO1 in cells [35]. A vast majority of the ubiquitination sites are solvent-exposed and found in protein segments with moderate to low structural stability (Figure 4), and thus, are readily accessible for ubiquitin tagging upon interaction with a suitable ubiquitin-ligase (such as CHIP, [17]).

Figure 4. Structural stability of the ubiquitination sites in hNQO1 in different ligation states (apo, no ligand bound; holo, saturated with FAD; dic, saturated with FAD and dicoumarol). Additional details on data representation can be found in the legend of Figure 2. The solvent accessible surface (ASA, %) is indicated in parentheses and calculated using GetArea and the PDB 2F1O as the average ± s.d. from eight monomers.

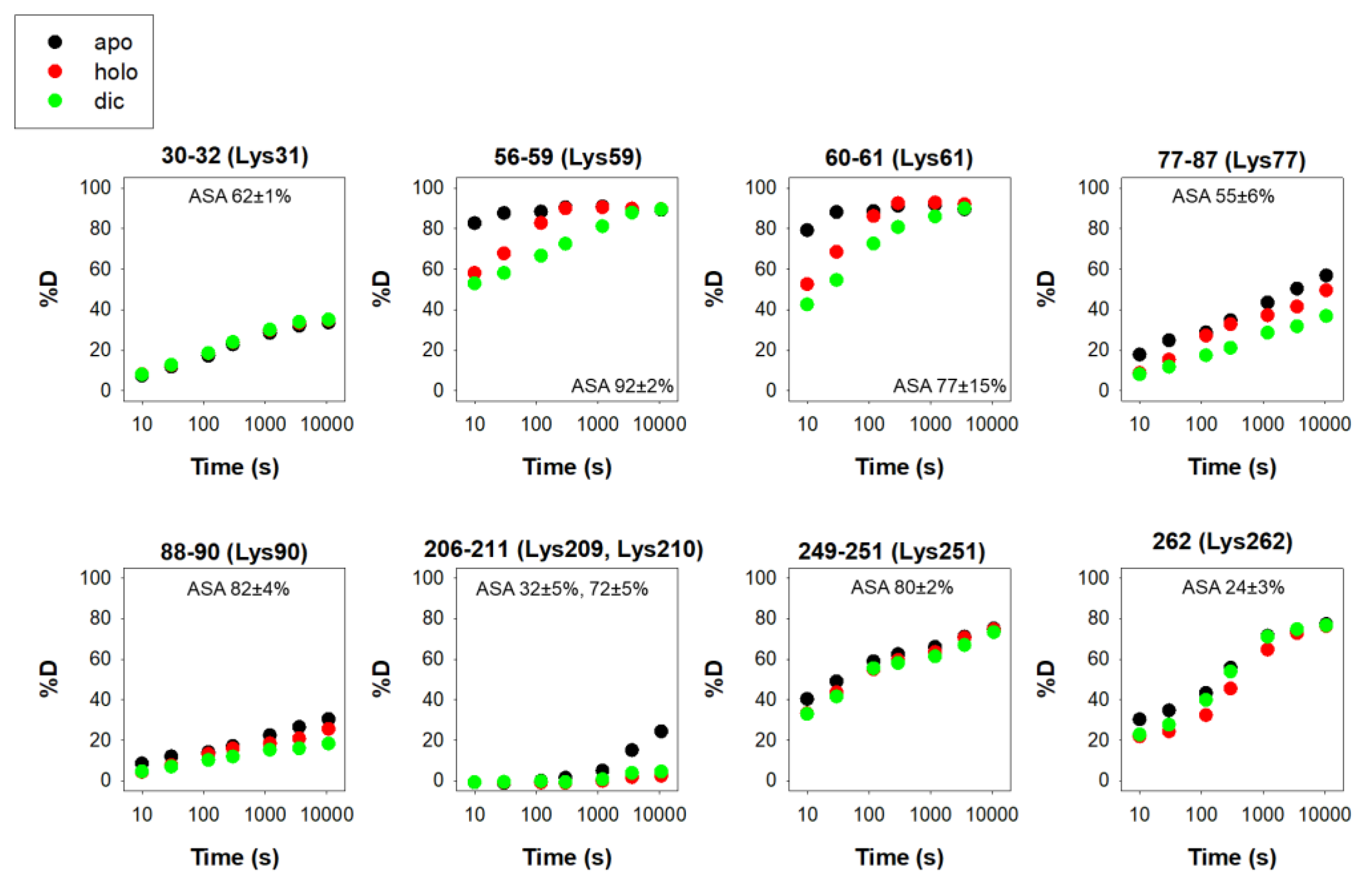

3.3. Acetylation

Until recently, acetylation of hNQO1 had been characterized only by high-throughput means, identifying nine sites with generally very high solvent exposure (logically, since Lys residues are often found on the protein surface) and typically in regions with moderate-to-low stability (Figure 5). However, Siegel and coworkers have recently described that acetylation of K33, K59, K61, K77, K90, K209, K251, K262 and K271 readily occurs upon in vitro exposure of recombinant hNQO1 to acetic anhydride or S-acetylglutathione [37]. It is interesting that these authors found helix 7 (residues 65–78) as one of the main targets for hNQO1 acetylation, since this region is next to the phosphosite S82 and the evolutionarily divergent site H80. Since all three phenomena (acetylation, phosphorylation and the variations R80 and H80) involve alterations in the electrostatic network important for FAD binding [30][31][32], I speculate that there could be some crosstalk between them in the modulation of NQO1 functionality in different mammalian species.

Figure 5. Structural stability of the acetylation sites in hNQO1 in different ligation states (apo, no ligand bound; holo, saturated with FAD; dic, saturated with FAD and dicoumarol). Additional details on data representation can be found in the legend of Figure 2. The solvent accessible surface area (ASA, %) is indicated in parenthesis and calculated using GetArea and the PDB 2F1O as the average ± s.d. from eight monomers.

In vitro acetylation of hNQO1 led to a 37% decrease in steady-state catalytic function [37]. Importantly, acetylation was highly susceptible to functional ligand binding (NADH mediated reduction of FAD largely prevented acetylation), and deacetylation at K262 and K271 was quickly catalyzed by different sirtuins in vitro [37]. This phenomenon is likely associated with the NADH-dependent localization of hNQO1 around microtubules [3], and also highlights the plasticity of hNQO1 functionality in different ligation states and different subcellular locations [2][3][28].

Studies from the laboratory using mimetic mutations (at K31 and K209) have shown that the effect of acetylation on hNQO1 activity may be mainly ascribed to the K31 site (see the mutant K31Q in Table 1). This mutant also showed a mild decrease in thermal stability, both as holo- and apo-protein (Table 2). The role of electrostatic interactions in the effects of acetylating K31 was also supported by the greater effects found for the charge-reversal K31E mutant (Table 1 and Table 2).

Table 1. Steady-state enzyme kinetic parameters for the reduction in DCPIP by hNQO1 WT and mutants at K31 and K209. Proteins were expressed and purified according to [28]. Activity was measured according to [24] using 20 µM DCPIP and 0–2 mM NADH at 25 °C. Data were fitted to the Michaelis–Menten equation.

| NQO1 Variant | kcat (s−1) | KM (NADH) (mM) | kcat/KM (s−1·mM−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 50 ± 4 | 0.54 ± 0.10 | 91 ± 18 |

| K31Q | 36 ± 4 | 0.44 ± 0.10 | 82 ± 20 |

| K31E | 32 ± 5 | 0.38 ± 0.08 | 86 ± 19 |

| K209Q | 43 ± 6 | 0.29 ± 0.10 | 147 ± 50 |

| K209E | 42 ± 5 | 0.30 ± 0.08 | 142 ± 40 |

Table 2. Thermal stability of hNQO1 variants at K31 and K209. Thermal denaturation was carried out by intrinsic fluorescence emission spectroscopy, as described in [32].

| NQO1 Variant | Ligation State 1 | Tm (°C) 2 |

|---|---|---|

| WT | Holo | 55.8 ± 0.5 |

| Apo | 52.0 ± 0.6 | |

| K31Q | Holo | 54.5 ± 0.1 |

| Apo | 50.5 ± 0.7 | |

| K31E | Holo | 53.3 ± 0.1 |

| Apo | 49.6 ± 0.6 | |

| K209Q | Holo | 55.4 ± 0.1 |

| Apo | 51.9 ± 0.3 | |

| K209E | Holo | 53.5 ± 0.1 |

| Apo | 50.8 ± 0.6 |

1 Apo indicates samples in which FAD has been stripped. Holo indicates proteins that were purified in the presence of 20 µM FAD. Protein concentration was 1 µM. 2 Average ± s.d. from four replicates.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/antiox12020379

References

- Beaver, S.K.; Mesa-Torres, N.; Pey, A.L.; Timson, D.J. NQO1: A target for the treatment of cancer and neurological diseases, and a model to understand loss of function disease mechanisms. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Proteins Proteom. 2019, 1867, 663–676.

- Salido, E.; Timson, D.J.; Betancor-Fernández, I.; Palomino-Morales, R.; Anoz-Carbonell, E.; Pacheco-García, J.L.; Medina, M.; Pey, A.L. Targeting HIF-1α Function in Cancer through the Chaperone Action of NQO1: Implications of Genetic Diversity of NQO1. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 747.

- Siegel, D.; Bersie, S.; Harris, P.; Di Francesco, A.; Armstrong, M.; Reisdorph, N.; Bernier, M.; de Cabo, R.; Fritz, K.; Ross, D. A redox-mediated conformational change in NQO1 controls binding to microtubules and α-tubulin acetylation. Redox Biol. 2021, 39, 101840.

- Carbonell, E.A.; Timson, D.J.; Pey, A.L.; Medina, M. The Catalytic Cycle of the Antioxidant and Cancer-Associated Human NQO1 Enzyme: Hydride Transfer, Conformational Dynamics and Functional Cooperativity. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 772.

- Clavería-Gimeno, R.; Velazquez-Campoy, A.; Pey, A.L. Thermodynamics of cooperative binding of FAD to human NQO1: Implications to understanding cofactor-dependent function and stability of the flavoproteome. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2017, 636, 17–27.

- Megarity, C.F.; Timson, D.J. Cancer-associated variants of human NQO1: Impacts on inhibitor binding and cooperativity. Biosci. Rep. 2019, 39, BSR20191874.

- Megarity, C.F.; Bettley, H.A.; Caraher, M.C.; Scott, K.A.; Whitehead, R.C.; Jowitt, T.A.; Gutierrez, A.; Bryce, R.A.; Nolan, K.A.; Stratford, I.J.; et al. Negative Cooperativity in NAD(P)H Quinone Oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1). Chembiochem 2019, 20, 2841–2849.

- Ross, D.; Siegel, D. The diverse functionality of NQO1 and its roles in redox control. Redox Biol. 2021, 41, 101950.

- Shendure, J.; Akey, J.M. The Origins, Determinants, and Consequences of Human Mutations. Science 2015, 349, 1478–1483.

- Manolio, T.A.; Fowler, D.M.; Starita, L.M.; Haendel, M.A.; MacArthur, D.G.; Biesecker, L.G.; Worthey, E.; Chisholm, R.L.; Green, E.D.; Jacob, H.J.; et al. Bedside Back to Bench: Building Bridges between Basic and Clinical Genomic Research. Cell 2017, 169, 6–12.

- Lek, M.; Karczewski, K.J.; Minikel, E.V.; Samocha, K.E.; Banks, E.; Fennell, T.; O’Donnell-Luria, A.H.; Ware, J.S.; Hill, A.J.; Cummings, B.B.; et al. Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. Nature 2016, 536, 285–291.

- McInnes, G.; Sharo, A.G.; Koleske, M.L.; Brown, J.E.; Norstad, M.; Adhikari, A.N.; Wang, S.; Brenner, S.E.; Halpern, J.; Koenig, B.A.; et al. Opportunities and challenges for the computational interpretation of rare variation in clinically important genes. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2021, 108, 535–548.

- Bagdasaryan, A.A.; Chubarev, V.N.; Smolyarchuk, E.A.; Drozdov, V.N.; Krasnyuk, I.I.; Liu, J.; Fan, R.; Tse, E.; Shikh, E.V.; Sukocheva, O.A. Pharmacogenetics of Drug Metabolism: The Role of Gene Polymorphism in the Regulation of Doxorubicin Safety and Efficacy. Cancers 2022, 14, 5436.

- van der Lee, M.; Allard, W.G.; Vossen, R.H.A.M.; Baak-Pablo, R.F.; Menafra, R.; Deiman, B.A.L.M.; Deenen, M.J.; Neven, P.; Johansson, I.; Gastaldello, S.; et al. Toward predicting CYP2D6-mediated variable drug response from CYP2D6 gene sequencing data. Sci. Transl. Med. 2021, 13, eabf3637.

- Venugopal, R.; Jaiswal, A.K. Nrf1 and Nrf2 positively and c-Fos and Fra1 negatively regulate the human antioxidant response element-mediated expression of NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase1 gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 14960–14965.

- Jaiswal, A.K. Regulation of genes encoding NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductases. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2000, 29, 254–262.

- Ross, D.; Siegel, D. Functions of NQO1 in Cellular Protection and CoQ10 Metabolism and its Potential Role as a Redox Sensitive Molecular Switch. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 595.

- Ma, Q. Role of Nrf2 in Oxidative Stress and Toxicity. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2013, 53, 401–426.

- Fowke, J.H.; Shu, X.-O.; Dai, Q.; Jin, F.; Cai, Q.; Gao, Y.-T.; Zheng, W. Oral Contraceptive Use and Breast Cancer Risk: Modification by NAD(P)H:Quinone Oxoreductase (NQO1) Genetic Polymorphisms. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2004, 13, 1308–1315.

- Hamachi, T.; Tajima, O.; Uezono, K.; Tabata, S.; Abe, H.; Ohnaka, K.; Kono, S. CYP1A1, GSTM1, GSTT1 and NQO1polymorphisms and colorectal adenomas in Japanese men. World J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 19, 4023–4030.

- Lienhart, W.; Gudipati, V.; Uhl, M.K.; Binter, A.; Pulido, S.A.; Saf, R.; Zangger, K.; Gruber, K.; Macheroux, P. Collapse of the native structure caused by a single amino acid exchange in humanNAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase1. FEBS J. 2014, 281, 4691–4704.

- Lienhart, W.; Strandback, E.; Gudipati, V.; Koch, K.; Binter, A.; Uhl, M.K.; Rantasa, D.M.; Bourgeois, B.; Madl, T.; Zangger, K.; et al. Catalytic competence, structure and stability of the cancer-associated R139W variant of the human NAD (P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO 1). FEBS J. 2017, 284, 1233–1245.

- Pacheco-Garcia, J.L.; Cagiada, M.; Tienne-Matos, K.; Salido, E.; Lindorff-Larsen, K.; Pey, A.L. Effect of naturally-occurring mutations on the stability and function of cancer-associated NQO1: Comparison of experiments and computation. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2022, 9, 1063620.

- Medina-Carmona, E.; Neira, J.L.; Salido, E.; Fuchs, J.E.; Palomino-Morales, R.; Timson, D.J.; Pey, A.L. Site-to-site interdomain communication may mediate different loss-of-function mechanisms in a cancer-associated NQO1 polymorphism. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, srep44532.

- Vankova, P.; Salido, E.; Timson, D.J.; Man, P.; Pey, A.L. A Dynamic Core in Human NQO1 Controls the Functional and Stability Effects of Ligand Binding and Their Communication across the Enzyme Dimer. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 728.

- Pacheco-Garcia, J.L.; Anoz-Carbonell, E.; Loginov, D.S.; Vankova, P.; Salido, E.; Man, P.; Medina, M.; Palomino-Morales, R.; Pey, A.L. Different phenotypic outcome due to site-specific phosphorylation in the cancer-associated NQO1 enzyme studied by phosphomimetic mutations. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2022, 729, 109392.

- Pacheco-Garcia, J.L.; Loginov, D.S.; Anoz-Carbonell, E.; Vankova, P.; Palomino-Morales, R.; Salido, E.; Man, P.; Medina, M.; Naganathan, A.N.; Pey, A.L. Allosteric Communication in the Multifunctional and Redox NQO1 Protein Studied by Cavity-Making Mutations. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1110.

- Pacheco-Garcia, J.L.; Anoz-Carbonell, E.; Vankova, P.; Kannan, A.; Palomino-Morales, R.; Mesa-Torres, N.; Salido, E.; Man, P.; Medina, M.; Naganathan, A.N.; et al. Structural basis of the pleiotropic and specific phenotypic consequences of missense mutations in the multifunctional NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 and their pharmacological rescue. Redox Biol. 2021, 46, 102112.

- Carmona, E.M.; Betancor-Fernández, I.; Santos, J.; Mesa-Torres, N.; Grottelli, S.; Batlle, C.; Naganathan, A.N.; Oppici, E.; Cellini, B.; Ventura, S.; et al. Insight into the specificity and severity of pathogenic mechanisms associated with missense mutations through experimental and structural perturbation analyses. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2019, 28, 1–15.

- Medina-Carmona, E.; Rizzuti, B.; Martín-Escolano, R.; Pacheco-García, J.L.; Mesa-Torres, N.; Neira, J.L.; Guzzi, R.; Pey, A.L. Phosphorylation compromises FAD binding and intracellular stability of wild-type and cancer-associated NQO1: Insights into flavo-proteome stability. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 125, 1275–1288.

- Pacheco-Garcia, J.L.; Loginov, D.; Rizzuti, B.; Vankova, P.; Neira, J.L.; Kavan, D.; Mesa-Torres, N.; Guzzi, R.; Man, P.; Pey, A.L. A single evolutionarily divergent mutation determines the different FAD-binding affinities of human and rat NQO1 due to site-specific phosphorylation. FEBS Lett. 2022, 596, 29–41.

- Carmona, E.M.; Fuchs, J.E.; Gavira, J.A.; Mesa-Torres, N.; Neira, J.L.; Salido, E.; Palomino-Morales, R.; Burgos, M.; Timson, D.; Pey, A.L. Enhanced vulnerability of human proteins towards disease-associated inactivation through divergent evolution. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2017, 26, 3531–3544.

- Luo, S.; Kang, S.S.; Wang, Z.-H.; Liu, X.; Day, J.X.; Wu, Z.; Peng, J.; Xiang, D.; Springer, W.; Ye, K. Akt Phosphorylates NQO1 and Triggers its Degradation, Abolishing Its Antioxidative Activities in Parkinson’s Disease. J. Neurosci. 2019, 39, 7291–7305.

- Siegel, D.; Anwar, A.; Winski, S.L.; Kepa, J.K.; Zolman, K.L.; Ross, D. Rapid Polyubiquitination and Proteasomal Degradation of a Mutant Form of NAD(P)H:Quinone Oxidoreductase 1. Mol. Pharmacol. 2001, 59, 263–268.

- Martínez-Limón, A.; Alriquet, M.; Lang, W.-H.; Calloni, G.; Wittig, I.; Vabulas, R.M. Recognition of enzymes lacking bound cofactor by protein quality control. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 12156–12161.

- Muñoz, I.G.; Morel, B.; Medina-Carmona, E.; Pey, A.L. A mechanism for cancer-associated inactivation of NQO1 due to P187S and its reactivation by the consensus mutation H80R. FEBS Lett. 2017, 591, 2826–2835.

- Siegel, D.; Harris, P.S.; Michel, C.R.; de Cabo, R.; Fritz, K.S.; Ross, D. Redox state and the sirtuin deacetylases are major factors that regulate the acetylation status of the stress protein NQO1. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1015642.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!