The black soldier fly (BSF), Hermetia illucens Linnaeus, is a large Stratiomyidae fly (13-20 mm in size) found worldwide, but it is believed to have originated in the Americas. It is frequently found in the tropics and temperate regions throughout the world. Although adapted primarily to these regions, it can tolerate wide extremes of temperature except when ovipositing. They are considered beneficial insects and non-pests. The adult fly does not have mouthparts, stingers, or digestive organs; thus, they do not bite or sting and do not feed during its short lifespan. They feed only as larvae and are, therefore, not associated with disease transmission. BSF larvae (BSFL) are voracious eaters of a wide range of organic wastes, decomposing and returning nutrients to the soil. Additionally, BSFL is an alternative protein source for aquaculture, pet food, livestock feed, and human nutrition.

- Black soldier fly

- BSF

- BSF larvae

- Hermetia illucens Linnaeus

- Stratiomyidae

- bioconversion

- biowaste treatment

- waste management

- food security

- sustainable farming

1. Introduction

Rapid growth in the global human population and urbanization have led to increasing demands for food production and organic waste management. As the needs for nutritious food continue to rise, it is critical to ensure current and future food security, reduce waste generation, and promote sustainable farming that includes residue reuse and waste valorization. The use of the Black soldier fly (BSF), Hermetia illucens L., an emerging green technology, represents an enormous potential in waste management. BSF can remarkably reduce a wide variety of wastes and concurrently offer valuable animal or human feed and oil with high nutrient composition.

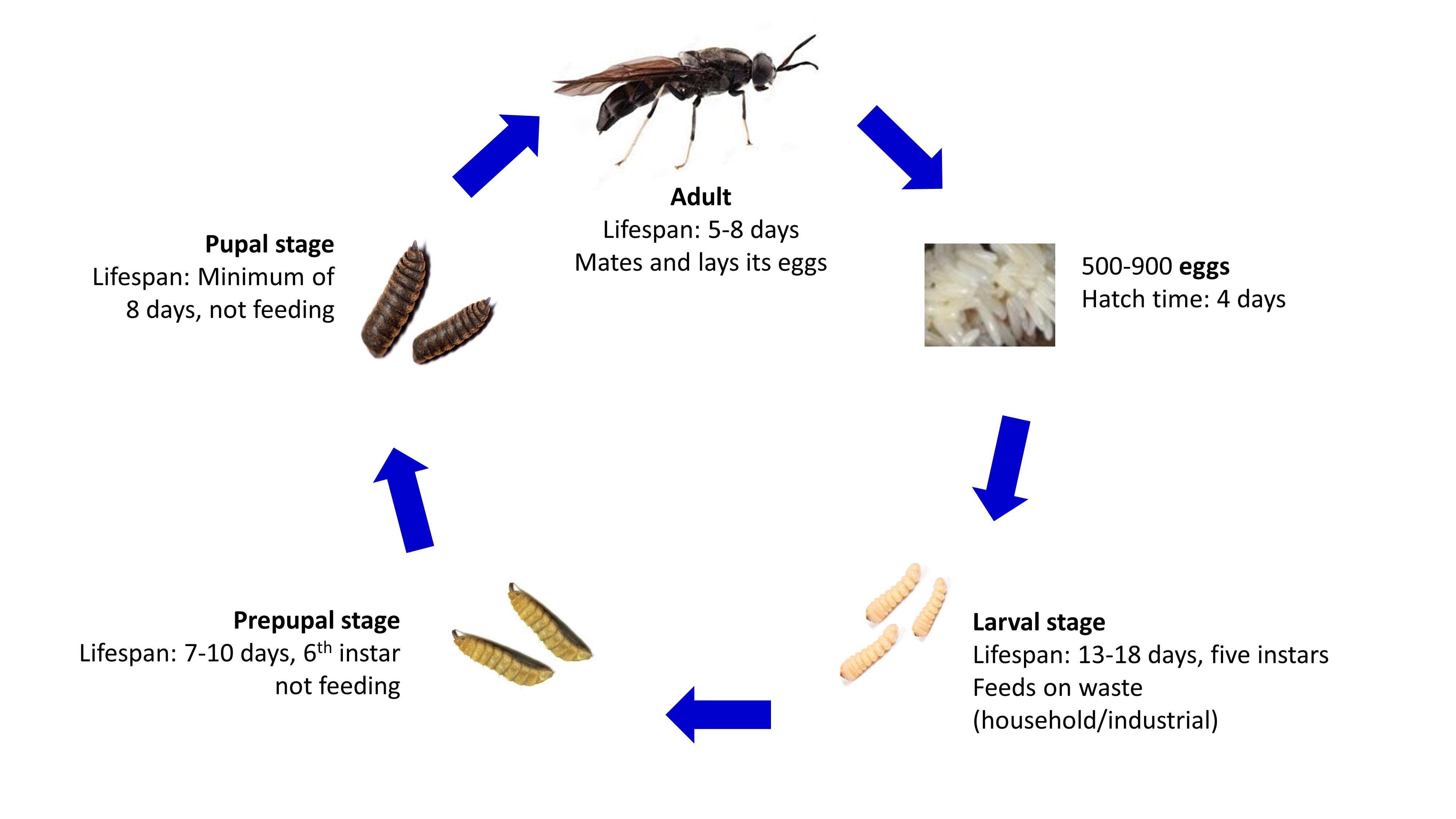

2. The life cycle of black soldier fly

The black soldier fly undergoes five main stages in its life cycle: egg, larval, prepupal, pupal, and adult stages [1]. The longest phase of its life cycle is spent in the larval and pupa stages, whereas the egg and adult stages are short. Females lay between 500 and 900 eggs [2]. On average, the eggs hatch in four days and vary with season, region, and temperature. There are six instars in the larval phase, and the larvae range in size from 1.8-20 mm, with 20-mm larvae being referred to as mature larvae. The larvae that emerged from the eggs initiate feeding immediately on diverse types of organic matter, including animal manure, decaying fruits and vegetables, and food waste, with consumption rates increasing considerably after the 3rd instar [3]. When the larvae reach the 6th instar, they undergo melanisation resulting in a darker coloration of the cuticle to become prepupae. In this stage, the insect empties its digestive tract and ceases feeding. The prepupae then migrate from their food source to dry crevices to metamorphose into pupae in 7-10 days. The pupal stage, during which larvae do not move nor eat for at least 8 days, ends with the adult emergence [1]. The adult fly feeds on nothing except water and relies on the fat stored in its larval stage. It does not harm crops, pollute the environment, spread diseases, or invade homes or restaurants but rather lives remotely from humans, maturing and mating primarily in shaded areas [3]. The fly mates and lays eggs for 5-8 days. Shortly after having oviposited, the female dies [1].

3. From waste to biofertilizer

Solid waste management, especially organic wastes, is one of the most pressing and serious environmental issues confronting cities in low- and middle-income countries[4][5]. The severity of this problem will continue to increase in the future onus to the trends of rapid industrialization, urbanization, and population growth [6][4]. The demand to develop efficient and sustainable methods of the waste management system has remained a daunting challenge.

Conventional composting methods require large land areas and long decomposition duration yet generate marginal revenues. The production of biogas from waste is a sustainable bioenergy resource, but it also has several disadvantages [7]. Anaerobic bacterial decomposition generates greenhouse gases such as methane (CH4), carbon dioxide (CO2), and nitrous oxide (N2O) associated with global warming. Emissions of enteric methane from manure are responsible for 14.5 % of all CH4 and N2O worldwide [7][8]. Other drawbacks include low loading rates, slow process, and the high cost of the digester [7]. Vermicomposting (use of earthworms) to degrade organic matter also has several constraints, such as fruit fly and gnat infestation, high maintenance (requires constant temperature and moisture monitoring), and high pathogen level compared to traditional composting [9][10]. Most of the wastes (particularly animal manure) require pre-composting (for up to 2 weeks) before vermicomposting [11].

Another approach for biowaste treatment that has gained growing recognition in recent years because of its technical simplicity and effectiveness is the use of black soldier fly. BSF larvae enable the bioconversion of various kinds of wastes including animal manure [12], food wastes, market waste, and other excrements into insect larval biomass, and organic compost [13]. The larvae can thrive in a wide array of decaying organic matter due to their large and powerful chewing mouthparts, rich intestinal microbiota, potent immune system, and high enzymatic activity, which allows them to metabolize molecules such as starches, proteins, and lipids [14]. The larvae convert organic waste material faster than worms used in vermicomposting [13]. Each larva can consume up to 200 mg of food waste per day. It can also accumulate and remove some toxic substances from compost [15]. Furthermore, manure treated with BSF larvae showed 47-fold lower greenhouse gas emissions than windrow composting [16].

4. From waste to animal feed and oil

Black soldier fly larvae (BSFL) are converters of organic waste into edible biomass ― proteins, lipids, peptides, amino acids, chitin, vitamins, and polypides. The proteins and amino acids have been used to produce animal feed, fish meal substitutes, and feedstuffs with a high digestibility [3], the nutritional value of which varies significantly on the type of substrates the larvae are fed [17]. Substrates rich in protein and oil are more conducive to the accumulation of protein and oil in BSF. Protein content ranges from 30-40 %, and oil 28-35 % [3]. Therefore, these insects offer alternative protein sources in the increasingly high costs of commercial feeds.

Defatted BSF larvae have also been shown promising fish meal substitutes [18]. Defatting of insects can be obtained by mechanical pressing of the crushed frozen larvae to enable the leakage of the intracellular fat or by extraction using petroleum ether [19]. The defatting process results in meals with larger protein values (~56.9 %) than the whole (non-defatted) larvae, comparable with soybean meals [20]. The insect protein concentrate can be used as an animal feed ingredient while the oils for animal nutrition, the chemical industry, and to produce biodiesel [19].

5. From waste to antimicrobial natural products

Little is known about the antimicrobial natural products from the black soldier fly. Recent years have seen a growing interest in the medicinal potential of BSF. Aside from chitin and chitosan [21][22], these insects have also been shown to produce antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) with potent activities against bacteria, fungi, parasites, and viruses. The production of these AMPs is induced by high bacterial loads (Gram-positive or Gram-negative) in the diet [3][23]. Such a wide spectrum of responses is a rich area for future research[24].

Amongst the classes of AMPs that have been recently identified from the larval extracts are cecropins and defensins [25]. The cecropin-like peptide 1 (CLP1) exhibits better efficacy than the antibiotic ampicillin towards Gram-negative bacteria such as Escherichia coli, Enterobacter aerogenes, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa with minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values in the range of 0.52–1.03, 1.03–2.07, and 1.03–2.07 μM, respectively [26]. The antimicrobial defensin-like peptides, DLP3 and DPL4 show antibacterial activity against Gram-positive bacteria, including drug-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains [27][28]. Additionally, the larvae modify the microflora of manure, potentially reducing the disease-causing pathogens such as E. coli and Salmonella enterica that affect the livestock [29]. Taken together, the black soldier fly is a promising resource for antibiotics research, highlighting the importance of further bioprospecting studies.

References

- G D P Da Silva; T Hesselberg; A Review of the Use of Black Soldier Fly Larvae, Hermetia illucens (Diptera: Stratiomyidae), to Compost Organic Waste in Tropical Regions. Neotropical Entomology 2019, 49, 151-162, 10.1007/s13744-019-00719-z.

- Agus Dana Perma; Ucu Julita; Lulu Lusianti F; Ramadhani Eka Putra; Mating Success and Reproductive Behavior of Black Soldier Fly Hermetia illucens L. (Diptera, Stratiomyidae) in Tropics. Journal of Entomology 2020, 17, 117-127, 10.3923/je.2020.117.127.

- Cuncheng Liu; Cunwen Wang; Huaiying Yao; Comprehensive Resource Utilization of Waste Using the Black Soldier Fly (Hermetia illucens (L.)) (Diptera: Stratiomyidae).. Animals 2019, 9, 349, 10.3390/ani9060349.

- Eukene Bensig; Mary Flores; Fleurdeliz Maglangit; Mary Joyceflores; Assessment of the Water Quality of Buhisan, Bulacao and Lahug Rivers, Cebu, Philippines Using Fecal and Total Coliform as Indicators. Current World Environment 2014, 9, 570-576, 10.12944/cwe.9.3.03.

- Fleurdeliz F Maglangit; Ritchelita P Galapate; Eukene O Bensig; Assessment of Nutrient and Sediment Loads in Buhisan, Bulacao and Lahug Rivers, Cebu, Philippines. International Journal of Sustainable Energy and Environmental Research 2016, 5, 8-13, 10.18488/journal.13/2016.5.1/13.1.8.13.

- Anshika Singh; Kanchan Kumari; An inclusive approach for organic waste treatment and valorisation using Black Soldier Fly larvae: A review. Journal of Environmental Management 2019, 251, 109569, 10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.109569.

- Marco A. El-Dakar; Remondah R. Ramzy; Martin Plath; Hong Ji; Evaluating the impact of bird manure vs. mammal manure on Hermetia illucens larvae. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 278, 123570, 10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.123570.

- Antoni Sánchez; Adriana Artola; Xavier Font; Teresa Gea; Raquel Barrena; David Gabriel; Miguel Ángel Sánchez-Monedero; Asunción Roig; María Luz Cayuela; Claudio Mondini; et al. Greenhouse gas emissions from organic waste composting. Environmental Chemistry Letters 2015, 13, 223-238, 10.1007/s10311-015-0507-5.

- Asoke Kumar Sannigrahi; Major Constraints in Popularising Vermicompost Technology in Eastern India. Modern Environmental Science and Engineering 2016, 2, 123-133, 10.15341/mese(2333-2581)/02.02.2016/008.

- Patrick Byambas; Jean Luc Hornick; Didier Marlier; Frederic Francis; Murat Eyvaz; Vermiculture in animal farming: A review on the biological and nonbiological risks related to earthworms in animal feed. Cogent Environmental Science 2019, 5, 1591328, 10.1080/23311843.2019.1591328.

- Sharma, Kavita; Garg, V.K.. Vermicomposting of Waste: A Zero-Waste Approach for Waste Management; Elsevier B.V.: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2019; pp. 133-164.

- Fen Zhou; Jeffery K. Tomberlin; Longyu Zheng; Ziniu Yu; Jibin Zhang; Developmental and waste reduction plasticity of three black soldier fly strains (Diptera: Stratiomyidae) raised on different livestock manures.. Journal of Medical Entomology 2013, 50, 1224-1230, 10.1603/ME13021.

- S.N. Rindhe; Manish Kumar Chatli; R.V. Wagh; AmanPreet Kaur; Nitin Mehta; Pavan Kumar; O.P. Malav; Black Soldier Fly: A New Vista for Waste Management and Animal Feed. International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences 2019, 8, 1329-1342, 10.20546/ijcmas.2019.801.142.

- Cíntia Almeida; Patrícia Rijo; Catarina Rosado; Bioactive Compounds from Hermetia Illucens Larvae as Natural Ingredients for Cosmetic Application. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 976, 10.3390/biom10070976.

- Francis K. Attiogbe; Nana Yaa K. Ayim; Joshua Martey; Effectiveness of black soldier fly larvae in composting mercury contaminated organic waste. Scientific African 2019, 6, e00205, 10.1016/j.sciaf.2019.e00205.

- Adeline Mertenat; Stefan Diener; Christian Zurbrügg; Black Soldier Fly biowaste treatment – Assessment of global warming potential. Waste Management 2019, 84, 173-181, 10.1016/j.wasman.2018.11.040.

- Thomas Spranghers; Matteo Ottoboni; Cindy Klootwijk; Anneke Ovyn; Stefaan Deboosere; Bruno De Meulenaer; Joris Michiels; Mia Eeckhout; Patrick De Clercq; Stefaan De Smet; et al. Nutritional composition of black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens) prepupae reared on different organic waste substrates. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 2016, 97, 2594-2600, 10.1002/jsfa.8081.

- GuoXia Wang; Kai Peng; Junru Hu; Cangjin Yi; Xiaoying Chen; Haomin Wu; Yanhua Huang; Evaluation of defatted black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens L.) larvae meal as an alternative protein ingredient for juvenile Japanese seabass (Lateolabrax japonicus) diets. Aquaculture 2019, 507, 144-154, 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2019.04.023.

- Achille Schiavone; Michele De Marco; Silvia Martínez; Sihem Dabbou; Manuela Renna; Josefa Madrid; Fuensanta Hernandez; Luca Rotolo; Pierluca Costa; Francesco Gai; et al. Nutritional value of a partially defatted and a highly defatted black soldier fly larvae (Hermetia illucens L.) meal for broiler chickens: apparent nutrient digestibility, apparent metabolizable energy and apparent ileal amino acid digestibility. Journal of Animal Science and Biotechnology 2017, 8, 1-9, 10.1186/s40104-017-0181-5.

- Ronghua Lu; Yanna Chen; Weipeng Yu; Mengjun Lin; Guokun Yang; Chaobin Qin; Xiaolin Meng; Yanmin Zhang; Hong Ji; Guoxing Nie; et al. Defatted black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens) larvae meal can replace soybean meal in juvenile grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idellus) diets. Aquaculture Reports 2020, 18, 100520, 10.1016/j.aqrep.2020.100520.

- Adelya Khayrova; Sergey Lopatin; Valery Varlamov; Black Soldier Fly Hermetia illucens as a Novel Source of Chitin and Chitosan. International Journal of Sciences 2019, 8, 81-86, 10.18483/ijsci.2015.

- Anuraga Jayanegara; Ratna P. Haryati; Ainun Nafisah; Pipih Suptijah; Muhammad Ridla; Erika B. Laconi; Derivatization of Chitin and Chitosan from Black Soldier Fly (Hermetia illucens) and Their Use as Feed Additives: An In vitro Study. Advances in Animal and Veterinary Sciences 2020, 8, 472-477, 10.17582/journal.aavs/2020/8.5.472.477.

- L. Gasco; A. Józefiak; M. Henry; Beyond the protein concept: health aspects of using edible insects on animals. Journal of Insects as Food and Feed 2020, in press, 1-28, 10.3920/jiff2020.0077.

- Fleurdeliz Maglangit; Yi Yu; Hai Deng; Bacterial pathogens: threat or treat (a review on bioactive natural products from bacterial pathogens). Natural Product Reports 2020, 10.1039/D0NP00061B, 1-40, 10.1039/d0np00061b.

- Ariane Müller; Diana Wolf; Herwig O. Gutzeit; The black soldier fly, Hermetia illucens – a promising source for sustainable production of proteins, lipids and bioactive substances. Zeitschrift für Naturforschung C 2017, 72, 351-363, 10.1515/znc-2017-0030.

- Soon-Ik Park; Sung Moon Yoe; A novel cecropin-like peptide from black soldier fly, Hermetia illucens : Isolation, structural and functional characterization. Entomological Research 2017, 47, 115-124, 10.1111/1748-5967.12226.

- Soon-Ik Park; Jong-Wan Kim; Sung Moon Yoe; Purification and characterization of a novel antibacterial peptide from black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens) larvae. Developmental & Comparative Immunology 2015, 52, 98-106, 10.1016/j.dci.2015.04.018.

- Soon-Ik Park; Sung Moon Yoe; Defensin-like peptide3 from black solder fly: Identification, characterization, and key amino acids for anti-Gram-negative bacteria. Entomological Research 2017, 47, 41-47, 10.1111/1748-5967.12214.

- F A Auza; S Purwanti; J A Syamsu; A Natsir; Antibacterial activities of black soldier flies (Hermetia illucens. l) extract towards the growth of Salmonella typhimurium, E.coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 2020, 492, 012024, 10.1088/1755-1315/492/1/012024.