Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Mycotoxin contamination has become one of the biggest hidden dangers of food safety, which seriously threatens human health. Understanding the mechanisms by which mycotoxins exert toxicity is key to detoxification. Ferroptosis is an adjustable cell death characterized by iron overload and lipid reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation and glutathione (GSH) depletion.

- aflatoxin B1

- ferroptosis

- lipid peroxidation

- mycotoxin

- iron metabolism

1. Introduction

Mycotoxins are toxic secondary metabolites produced by a variety of fungi, with characteristics such as enrichment, stability, synergism, and territoriality [1]. Mycotoxins such as aflatoxin (AF), T-2 toxin, zearalenone (ZEN), ochratoxin, and deoxynivalenol (DON, vomitoxin) have drawn much attention due to their serious effects on human and animal health [2]. Aflatoxin mainly affects the liver, kidney, intestine, and immune function, and has the greatest harm to pigs, poultry, and ruminants. Zearalenone is mainly harmful to the reproductive system and can cause abortion in animals, dead fetuses, mummified fetuses, and weak fetuses. The excessive content of zearalenone in feed causes the repeated infertility of sows in many breeding pig farms [2]. The T-2 toxin is mainly produced by Fusarium graminearum and can disrupt the lymphatic system, resulting in decreased immunity in animals [3], which also damages the reproductive system, resulting in problems such as reduced egg production with poor eggshell quality and increased egg cleavage rate with thin protein [4]. The gastrointestinal tract is the main target organ for vomitoxin or DON invasion in livestock and poultry which can cause reduced feed intake, refusal to eat, and frequent vomiting, leading to malnutrition and long-term failure. Pocine aflatoxin and fumonisin mainly damage the immune, reproductive, and digestive systems, resulting in decreased immunity, irregular estrus, feed indigestion, digestive tract mucosal damage, and prolonged animal suffering [5]. Moreover, the living environments of fungi are extensive, including grain, feed, and other crops, which are contaminated by fungi mainly in the transportation, storage, processing, and marketing process. Long-term consumption of these feeds by livestock and poultry leads to the accumulation of toxins, resulting in serious damage to some metabolic organs such as the liver and kidneys, and even the risk of meat and dairy contamination increases, causing huge economic losses in the breading industry worldwide [6][7][8]. According to reports, at least 25% of global feed production suffered from mycotoxin contamination, the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (US-FAO) estimates that the world’s losses due to mycotoxin contamination, amounting to hundreds of billions of dollars a year [9]. Mycotoxin contamination has become a huge challenge to control in recent years due to global warming, with a higher incidence of mycotoxins in eastern Kenya due to hot and humid weather, whereas cold and dry northern regions such as Canada have the lowest incidence of mycotoxins [10]. If Aspergillus flavus (A. flavus) continues to grow indefinitely under high temperatures and drought conditions, posing a serious threat to the health of human beings and animals [11].

The common features of fungal toxins in humans and animals mainly include liver, kidney, and intestinal injury, and even immunosuppression, which are partly caused by cellular inflammation, oxidative stress, apoptosis, autophagy, ferroptosis, and other forms of cell death [8][12][13][14][15]. Recent studies showed that mycotoxins can induce liver toxicity, acute kidney injury, or intestinal damage by promoting ferroptosis, manifested by the death of tubule epithelial cells and hepatocytes, and damage to the intestinal barrier function and gut microbial homeostasis [12][15][16]. Interestingly, treatment of cells with the ferroptosis inhibitor ferrostatin-1 significantly restored the toxicity of mycotoxins (such as T-2 toxin) and also found that T-2 toxin triggered ferroptosis by inducing ROS, suggesting that ferroptosis is related to T-2 toxin-related toxicity and could be a potential target for the treatment of mycotoxicosis [17]. In addition, the elevated hepatorenal iron levels and the activation of lipid peroxidation caused by various reasons create pathological conditions for the occurrence of hepatocyte or renal tubular ferroptosis [18][19]. Ferroptosis, a form of cell death typically characterized by iron deposition and lipid peroxidation, was formally proposed in 2012 [20]. It has been demonstrated that ferroptosis is also associated with pathological mechanisms of ischemic and fibrotic damage in multiple organs, including cardiomyocyte injury caused by mycotoxin [21][22][23].

Moreover, with the in-depth study of ferroptosis, more and more evidence presented that ferroptosis is associated with cancer and cardiovascular disease [20][24]. This finding helps to develop a new cell protection strategy to protect cells in cancer and heart diseases by inhibiting ferroptosis. Meanwhile, selective induction of ferroptosis has emerged as a potential therapeutic strategy for some cancers [20]. As cell metabolism determines cell death, researchers have attempted to intervene by interfering with ferroptosis molecules and related signaling cascades to reduce cell damage and delay or reverse cell death based on the adaptability of ferroptosis molecules [25]. Therefore, blocking the ferroptosis process of multiple organs may be an effective way to treat mycotoxicosis.

2. Mechanisms of Ferroptosis

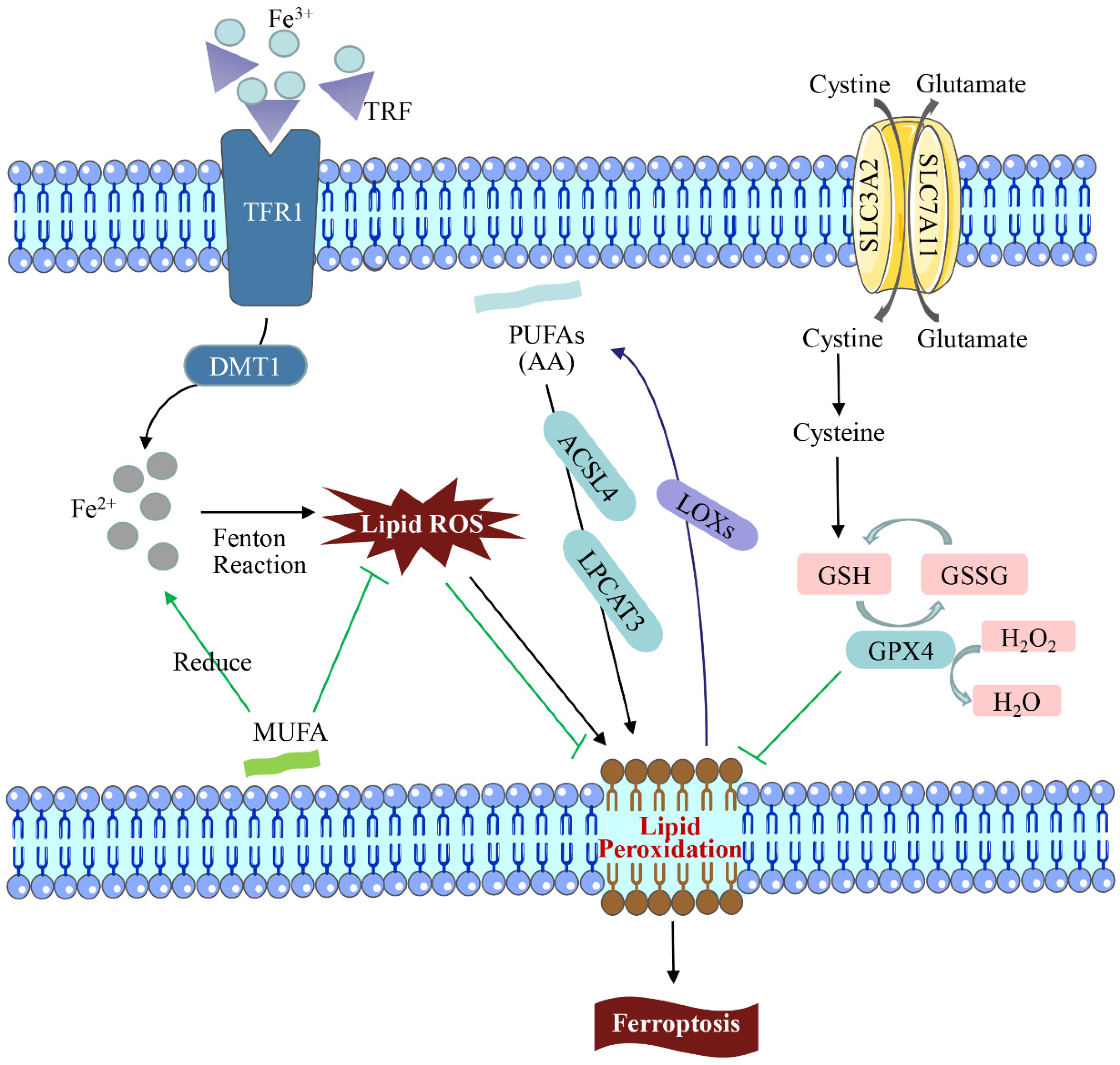

Cell death includes apoptosis, ferroptosis, pyroptosis, lysosome-dependent cell death, autophagy-dependent cell death (autologous death), etc. [26]. Among them, ferroptosis is a non-apoptotic cell death that is different from other death modes in recent years. It is primarily caused by an excessive accumulation of intracellular ROS, impaired iron ion metabolism, and imbalance of cellular lipid peroxidation, which results in decreased glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) activity, elevated intracellular free iron levels, and accumulation of lipid peroxide [27]. As a result of an increase in free iron in a cell, ferroptosis is manifested, which produces more reactive oxygen species and oxidizes polyunsaturated fatty acids on the cell membrane to lipid peroxides via the Fenton reaction. However, it can also catalyze lipid peroxides into toxic lipid radicals, leading to cell death [28]. Ferroptosis has unique cellular morphological, biochemical, and genetic characteristics [29]. Ferroptosis differs from other programmed cell death forms such as apoptosis and pyroptosis in that the morphological changes are driven primarily by changes in mitochondrial structure. Consequently, the volume is reduced, the structural integrity is lost, and the membrane density increases [30]. In 2003, the Stockwell team found that Erastin could induce tumor cell death, and the process was not affected by apoptosis, necrosis, and autophagic cell death inhibitors, showing obvious iron dependence and oxidative dependence [31]. The lipid ROS level in the solute of tumor cells treated with Erastin increased in a time-dependent manner until cell death, which could be effectively blocked by iron chelators and lipophilic antioxidants [32]. It can be seen that excessive accumulation of iron-dependent lipid peroxides becomes the culprit inducing ferroptosis (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Regulation of the ferroptosis pathway. In the iron cycle, excessive amounts of transferrin (TRF/TF) after binding to trivalent iron (Fe3+) may lead to iron overload, catalytic peroxidation, and accumulation of excessive intracellular ROS, resulting in DNA and mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) damage. Lipid peroxidation (LPO) is the main cause of ferroptosis. LPO attacks PUFAs and expands the oxidation reaction under the action of lipoxygenases (LOXs), causing damage. GPX4 can catalyze the conversion of GSH into GSSG and reduce the intracellular toxic lipid peroxides or free H2O2 into water. The consumption and activity reduction of GSH and GPX4 in the ferroptosis mechanism led to the decrease in ROS accumulation and LPO scavenging ability, which leads to ferroptosis.

3. Role of Ferroptosis in Mycotoxicosis Diseases

In recent years, the contamination of mycotoxins has gradually become more serious with global warming, resulting in feed ingredients being contaminated with multiple mycotoxins simultaneously [33]. The common mycotoxins produced are AFB1, ZEN, T-2 toxin, patulin (PAT), etc. According to statistics, more than 25% of the world’s crops are contaminated by mycotoxins every year, increasing the probability and mortality of livestock and poultry infections and causing huge economic losses in agriculture [34]. Mycotoxin contamination has become an urgent problem that threatens human food safety. Due to the cumulative effect of mycotoxins, with the aggregation of the food chain, it has become one of the environmental pollutants that seriously threaten human health [35]. Therefore, it is urgent to explore measures to inhibit mycotoxicosis. The LF, a member of the TRF family, has been reported to have broad-spectrum antibacterial, antioxidant, anticancer, and other biological functions, and it is effective in alleviating fungal toxins as one of the active ingredients of antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) [36]. Ferroptosis is known to be activated by TRF, and in studies of ferroptosis and AFB1, ferroptosis and DON, ferroptosis and ZEN, and ferroptosis and T-2 toxin, it was found that exploring the link between ferroptosis and fungal toxins could contribute to a breakthrough in treating mycotoxicosis (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Mycotoxin regulation ferroptosis diagram. The livestock and poultry are fed with feed contaminated by mycotoxins such as aflatoxin, zearalenone, T-2 toxin, and patulin, which promotes the production of ROS, down-regulates the expression levels of ferroptosis-related factors such as SLC7A11, Nrf2, SLC7A11, and GPX4, induces the damage of the biomacromolecular structure and oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and leads to ferroptosis.

3.1. AFB1 and Ferroptosis

The most toxic and carcinogenic mycotoxin known is AFB1, a secondary metabolite of A. flavus and Aspergillus fungi (A. fungi) displayed that AFB1-induced cardiotoxicity is associated with ferroptosis regulation [22]. AFB1 induced lipid peroxidation and increased the expression of ferroptosis activators (TRF and solute carrier family 11 Member 2) by promoting the production of ROS. At the same time, concurrent exposure to AFB1 promoted the accumulation of LPO and the deposition of 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE) and 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine (8-OHdG), exacerbating hepatocellular carcinoma [37]. Interestingly, exogenous Fe2+ can inhibit the growth of A. flavus by inducing ferroptosis of A. flavus spores [38]. Moreover, MIL-101 (Fe) is a typical iron-containing metal-organic framework that can effectively adsorb AFB1; the iron-containing nanomaterial (PCN-223(Fe)) has good peroxidase-like activity and can sensitively detect AFB1 in milk by constructing an immunosorbent assay [39][40]. Iron therapy has been used to relieve clinical symptoms and improve prognosis in patients with chronic kidney disease [41]. It can be seen that nanomaterials have great potential in the application of AFB1.

3.2. Zearalenone and Ferroptosis

Zearalenone (ZEA) is a non-steroidal estrogenic mycotoxin produced by Fusarium fungi. Global mycotoxin monitoring reports in the past 10 years have shown that ZEA can be detected in 45% of grains (such as corn, wheat, and soybeans) [1][42]. In 2022, a research team found that ZEN could cause certain damage to mouse sperm, and ferroptosis was involved in this process. This experiment found that the sperm motility and concentration of mice decreased significantly, and the testicular seminiferous tubule structure and antioxidant defense system were also damaged after ZEN exposure, which led to blocked spermatogenesis [43]. Furthermore, it was also noted that ZEN could activate ferroptosis-related signaling pathways and inhibit the expression levels of Nrf2, SLC7A11, and GPX4, resulting in excessive accumulation of lipid peroxides and high expression of 4-HNE protein in mouse testis, while the administration of Ferrostatin-1, an iron shedding inhibitor, at 1.5 mg/kg had the best repairing effect, which was mainly manifested by upregulating the expression of SLC7A11 and GPX4 proteins by upregulating Nrf2 expression, reducing iron accumulation and reversing ZEA-induced ferroptosis [43]. Therefore, paying attention to the mechanism of ferroptosis may provide new insights for alleviating the toxic effects of ZEN on livestock and poultry.

3.3. T-2 Toxin and Ferroptosis

The T-2 toxin is the most toxic of type A trichothecenes produced by Fusarium fungi. In nature, Fusarium is ubiquitous in barley, wheat, corn, and oats, which can reproduce in large quantities and produce T-2 toxin under suitable conditions [3][4][44]. The physical and chemical properties of T-2 toxin are stable and difficult to remove in the processing of ordinary food and feed, causing great harm to livestock and poultry production by triggering oxidative stress and apoptosis-related pathways [44][45]. A recent study has confirmed that ferroptosis is the result of T-2 toxin-related toxicity and pointed out in detail that T-2 toxin enhanced RAS selective lethal compound 3 (RSL3)-and erastin-induced cell death, but the treatment of ferrostatin-1 significantly restored the sensitization of T-2 toxin, indicating that iron shedding plays an important role in T-2 toxin-induced cytotoxicity [45]. Here, RSL3 and Erastin were used to induce ferroptosis. At the same time, ferrostatin-1, in this experiment, increases lipid ROS levels and down-regulates SLC7A11-induced ferroptosis, proving that ferroptosis is a potential target for treating mycotoxin poisoning [45].

3.4. Patulin and Ferroptosis

As a toxic fungal secondary metabolite, patulin is widely found in fruits and vegetables, grains, nuts, and other foods and Chinese herbal medicines. It can enter the body through food intake, skin contact, and other ways, which poses a serious threat to the health of humans and animals [15][17]. Patulin has genotoxicity, immunotoxicity, reproductive toxicity, and other toxicities, which can damage the intestine, kidney, liver, and other organs. The toxic mechanisms of patulin include the induction of biological macromolecular structure damage, induction of oxidative stress damage, induction of autophagy, and destruction of intestinal flora homeostasis [34]. It is widely believed that oxidative stress is a key mechanism underlying ferroptosis in fungal poisoning [42][46]. Some researchers found that patulin promoted rsl3-induced ferroptosis in renal cells by inhibiting the slc7a11-cystine-cysteine-glutathione antioxidant system [47]. Another study confirmed that short-term high-dose intake of PAT resulted in acute kidney injury in mice, and the ferroptosis signaling pathway was also found to be enriched to a higher degree in the assay [15]. Transcriptome sequencing and electron microscopy showed their involvement in iron shedding and autophagy. In addition to inhibiting the antioxidant system, PAT promoted the expression of ACL4, LC3, and ferritin light chain (FTL), leading to an autophagy-dependent iron failure [7]. In particular, co-exposure to fungal toxins exacerbated colonic damage in mice by inducing mitochondrial damage and ferroptosis [16]. In general, these findings will provide a new perspective for finding effective therapeutic approaches under patulin exposure.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/toxics11040395

References

- Alshannaq, A.; Yu, J.H. Occurrence, Toxicity, and Analysis of Major Mycotoxins in Food. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2017, 14, 632.

- Al-Jaal, B.A.; Jaganjac, M.; Barcaru, A.; Horvatovich, P.; Latiff, A. Aflatoxin, fumonisin, ochratoxin, zearalenone and deoxynivalenol biomarkers in human biological fluids: A systematic literature review, 2001–2018. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2019, 129, 211–228.

- Li, Y.; Wang, Z.; Beier, R.C. T-2 toxin, a trichothecene mycotoxin: Review of toxicity, metabolism, and analytical methods. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 3441–3453.

- Yang, X.; Liu, P.; Cui, Y. Review of the Reproductive Toxicity of T-2 Toxin. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 727–734.

- Yang, C.; Song, G.; Lim, W. Effects of mycotoxin-contaminated feed on farm animals. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 389, 122087.

- Lee, H.J.; Ryu, D. Worldwide Occurrence of Mycotoxins in Cereals and Cereal-Derived Food Products: Public Health Perspectives of Their Co-occurrence. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 7034–7051.

- Guo, H.; Wang, P.; Liu, C.; Zhou, T.; Chang, J.; Yin, Q.; Wang, L.; Jin, S.; Zhu, Q.; Lu, F. Effects of Compound Mycotoxin Detoxifier on Alleviating Aflatoxin B1-Induced Inflammatory Responses in Intestine, Liver and Kidney of Broilers. Toxins 2022, 14, 665.

- Yue, K.; Liu, K.L.; Zhu, Y.D.; Ding, W.L.; Xu, B.W.; Shaukat, A.; He, Y.F.; Lin, L.X.; Zhang, C.; Huang, S.C. Novel Insights into Total Flavonoids of Rhizoma Drynariae against Meat Quality Deterioration Caused by Dietary Aflatoxin B1 Exposure in Chickens. Antioxidants 2023, 30, 83.

- Cao, Q.Q.; Lin, L.X.; Xu, T.T.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, C.D.; Yue, K.; Huang, S.C.; Dong, H.J.; Jian, F.C. Aflatoxin B1 alters meat quality associated with oxidative stress, inflammation, and gut-microbiota in sheep. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 225, 112754.

- Zingales, V.; Taroncher, M.; Martino, P.A.; Ruiz, M.J.; Caloni, F. Climate Change and Effects on Molds and Mycotoxins. Toxins 2022, 14, 445.

- Almeida, F.; Rodrigues, M.L.; Coelho, C. The Still Underestimated Problem of Fungal Diseases Worldwide. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 214.

- Huang, S.; Lin, L.; Wang, S.; Ding, W.; Zhang, C.; Shaukat, A.; Xu, B.; Yue, K.; Zhang, C.; Liu, F. Total Flavonoids of Rhizoma Drynariae Mitigates Aflatoxin B1-Induced Liver Toxicity in Chickens via Microbiota-Gut-Liver Axis Interaction Mechanisms. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 819.

- Guo, Y.; Balasubramanian, B.; Zhao, Z.H.; Liu, W.C. Marine algal polysaccharides alleviate aflatoxin B1-induced bursa of Fabricius injury by regulating redox and apoptotic signaling pathway in broilers. Poult. Sci. 2021, 100, 844–857.

- Yin, S.; Liu, X.; Fan, L.; Hu, H. Mechanisms of cell death induction by food-borne mycotoxins. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 58, 1406–1417.

- Hou, Y.; Wang, S.; Jiang, L.; Sun, X.; Li, J.; Wang, N.; Liu, X.; Yao, X.; Zhang, C.; Deng, H.; et al. Patulin Induces Acute Kidney Injury in Mice through Autophagy-Ferroptosis Pathway. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 6213–6223.

- Lin, J.; Zuo, C.; Liang, T. Lycopene alleviates multiple-mycotoxin-induced toxicity by inhibiting mitochondrial damage and ferroptosis in the mouse jejunum. Food Funct. 2022, 13, 11532–11542.

- Srinivasan, R.; Ashutosh, B.; Myunghee, K. The effects of mycotoxin patulin on cells and cellular components. Trends. Food Sci. Tech. 2019, 83, 99–113.

- Feng, X.; Wang, S.; Sun, Z.; Dong, H.; Yu, H.; Huang, M.; Gao, X. Ferroptosis Enhanced Diabetic Renal Tubular Injury via HIF-1α/HO-1 Pathway in db/db Mice. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 626390.

- Chen, J.; Li, X.; Ge, C.; Min, J.; Wang, F. The multifaceted role of ferroptosis in liver disease. Cell Death Differ. 2022, 29, 467–480.

- Mou, Y.; Wang, J.; Wu, J.; He, D.; Zhang, C.; Duan, C.; Li, B. Ferroptosis, a new form of cell death: Opportunities and challenges in cancer. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2019, 12, 34.

- Li, Y.; Feng, D.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, R.; Tian, D.; Liu, D.; Zhang, F.; Ning, S.; Yao, J.; et al. Ischemia-induced ACSL4 activation contributes to ferroptosis-mediated tissue injury in intestinal ischemia/reperfusion. Cell Death Differ. 2019, 26, 2284–2299.

- Zhao, L.; Feng, Y.; Xu, Z.J.; Zhang, N.Y.; Zhang, W.P.; Zuo, G.; Khalil, M.M.; Sun, L.H. Selenium mitigated aflatoxin B1-induced cardiotoxicity with potential regulation of 4 selenoproteins and ferroptosis signaling in chicks. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2021, 154, 112320.

- Zhou, J.; Tan, Y.; Wang, R.; Li, X. Role of Ferroptosis in Fibrotic Diseases. J. Inflamm. Res. 2022, 15, 3689–3708.

- Fang, X.; Wang, H.; Han, D.; Xie, E.; Yang, X.; Wei, J.; Gu, S.; Gao, F.; Zhu, N.; Yin, X.; et al. Ferroptosis as a target for protection against cardiomyopathy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 2672–2680.

- Qiu, Y.; Cao, Y.; Cao, W.; Jia, Y.; Lu, N. The Application of Ferroptosis in Diseases. Pharmacol. Res. 2020, 159, 104919.

- Tang, D.; Kang, R.; Berghe, T.V.; Vandenabeele, P.; Kroemer, G. The molecular machinery of regulated cell death. Cell Res. 2019, 29, 347–364.

- Hirschhorn, T.; Stockwell, B.R. The development of the concept of ferroptosis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2019, 133, 130–143.

- Zheng, J.; Conrad, M. The Metabolic Underpinnings of Ferroptosis. Cell Metab. 2020, 32, 920–937.

- Xie, Y.; Hou, W.; Song, X.; Yu, Y.; Huang, J.; Sun, X.; Kang, R.; Tang, D. Ferroptosis: Process and function. Cell Death Differ. 2016, 23, 369–379.

- Yang, C.; Wang, T.; Zhao, Y.; Meng, X.; Ding, W.; Wang, Q.; Liu, C.; Deng, H. Flavonoid 4,4’-dimethoxychalcone induced ferroptosis in cancer cells by synergistically activating Keap1/Nrf2/HMOX1 pathway and inhibiting FECH. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2022, 188, 14–23.

- Dixon, S.J.; Lemberg, K.M.; Lamprecht, M.R.; Skouta, R.; Zaitsev, E.M.; Gleason, C.E.; Patel, D.N.; Bauer, A.J.; Cantley, A.M.; Yang, W.S.; et al. Ferroptosis: An iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell 2012, 149, 1060–1072.

- Liou, G.Y.; Storz, P. Reactive oxygen species in cancer. Free Radic. Res. 2010, 44, 479–496.

- Pinotti, L.; Ottoboni, M.; Giromini, C.; Dell’Orto, V.; Cheli, F. Mycotoxin Contamination in the EU Feed Supply Chain: A Focus on Cereal Byproducts. Toxins 2016, 8, 45.

- Tolosa, J.; Rodríguez-Carrasco, Y.; Ruiz, M.J.; Vila-Donat, P. Multi-mycotoxin occurrence in feed, metabolism and carry-over to animal-derived food products: A review. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2021, 158, 112661.

- Liew, W.P.; Mohd-Redzwan, S. Mycotoxin: Its Impact on Gut Health and Microbiota. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2018, 8, 60.

- Xiao, H.; Shao, F.; Wu, M.; Ren, W.; Xiong, X.; Tan, B.; Yin, Y. The application of antimicrobial peptides as growth and health promoters for swine. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2015, 6, 19.

- Asare, G.A.; Bronz, M.; Naidoo, V.; Kew, M.C. Interactions between aflatoxin B1 and dietary iron overload in hepatic mutagenesis. Toxicology 2007, 234, 157–166.

- Yao, L.; Zhang, T.; Peng, S.; Xu, D.; Liu, Z.; Li, H.; Hu, L.; Mo, H. Fe2+ protects postharvest pitaya (Hylocereus undulatus britt) from Aspergillus. flavus infection by directly binding its genomic DNA. Food Chem. 2022, 5, 100135.

- Liu, Y.Q.; Song, C.G.; Ding, G.; Yang, J.; Wu, J.R.; Wu, G.X.; Zhang, M.Z.; Song, C.L.; Guo, L.P.; Qin, J.C.; et al. High-Performance Functional Fe-MOF for Removing Aflatoxin B1 and Other Organic Pollutants. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 9, 2102480.

- Peng, S.; Li, K.; Wang, Y.X.; Li, L.; Cheng, Y.H.; Xu, Z. Porphyrin NanoMOFs as a catalytic label in nanozyme-linked immunosorbent assay for Aflatoxin B1 detection. Anal. Biochem. 2022, 655, 114829.

- Macdougall, I.C. Intravenous iron therapy in patients with chronic kidney disease: Recent evidence and future directions. Clin. Kidney J. 2017, 10 (Suppl. S1), i16–i24.

- Gruber, D.C.; Jenkins, T.; Schatzmayr, G. Global mycotoxin occurrence in feed: A ten-year survey. Toxins 2019, 11, 375.

- Li, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Cui, H. Effect of Zearalenone-Induced Ferroptosis on Mice Spermatogenesis. Animals 2022, 12, 3026.

- Zhuang, Z.; Yang, D.; Huang, Y.; Wang, S. Study on the apoptosis mechanism induced by T-2 toxin. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e83105.

- Wang, G.; Qin, S.; Zheng, Y.; Xia, C.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, L.; Yao, J.; Yi, Y.; Deng, L. T-2 Toxin Induces Ferroptosis by Increasing Lipid Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) and Downregulating Solute Carrier Family 7 Member 11 (SLC7A11). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 15716–15727.

- Li, J.; Cao, F.; Yin, H.L. Ferroptosis: Past, present and future. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 88.

- Chen, H.; Cao, L.; Han, K.; Zhang, H.; Cui, J.; Ma, X.; Zhao, S.; Zhao, C.; Yin, S.; Fan, L.; et al. Patulin disrupts SLC7A11-cystine-cysteine-GSH antioxidant system and promotes renal cell ferroptosis both in vitro and in vivo. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2022, 166, 113255.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!